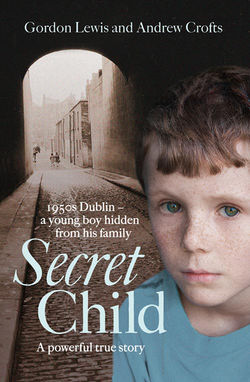

Читать книгу Secret Child - Andrew Crofts - Страница 5

Chapter One Going Home

ОглавлениеThe flight was delayed but none of the passengers milling around the lounge seemed to mind too much. There was something of a party atmosphere at that end of the terminal at JFK that day, which added to my own sense of excitement at my impending adventure.

I felt strangely nervous considering how many times I had boarded flights before. This trip, however, was going to be different to the usual round of international business meetings and holidays. This was literally a trip into the unknown, back into a past filled with dark secrets.

It seemed like the whole flight was going to be packed with Irish Americans heading home for the St Patrick’s Day celebrations, many of them wearing something green for the occasion, and some of them already cheered by a couple of pints of Guinness, taken to pass the time. I deliberately avoided eye contact with everyone, wanting to keep myself to myself, protecting my thoughts, preparing myself for whatever might be awaiting me at the other end of the transatlantic flight. The last thing I wanted was to fall into a conversation where someone started asking me questions about my plans for the next few days.

To give myself something to do I pulled the small envelope out of my jacket pocket and stared for the hundredth time at the modest collection of black-and-white photographs it contained. I had stared at them so long and so hard over the previous few months I knew every faded detail by heart. It was like looking into a different world; one that should have been joined to mine by memories and stories shared by previous generations, but was in fact quite alien. I might as well have been looking at pictures of strangers, and those pictures on their own were never going to give up their secrets, however many times I studied them.

‘American Airlines flight to Dublin, Ireland is ready for boarding.’ The announcement made me jump and raised a jovial cheer from some of the revellers at the bar. ‘Will First and Business Class passengers please proceed to the boarding gate.’

I slipped the photos back into my pocket and stood up, walking through to my seat without talking to anyone, only half hearing the conversations going on around me and gratefully accepting a glass of champagne from the smiling stewardess as I settled down and stared out of the window at the tarmac, wanting the flight to be over so that I could get my adventure started. I realised that my nerves were partly caused by fear of what I was about to find out and partly by the thought that I might not find out anything at all. I did not want to have to return to New York none the wiser as to the events surrounding my birth and the early years, which my family seemed determined to keep shrouded in mystery.

Extracting even the barest facts from my cousin, Denis, had been an agony. Anyone would have thought I was trying to pull his teeth out rather than ask a few questions, as each one was met with a sigh and the barest of monosyllabic answers that he could get away with. If it hadn’t been for the fact that I was buying him dinner and that he was bound by politeness to stay at the restaurant table for the duration of the meal, he would have made his excuses and left the moment I raised the subject of the past. When I finally had to let him off the hook he swore blind he had told me everything he knew, but I was not at all sure he was telling the truth. That generation seemed to find it an agony to talk about anything personal or emotional, however far in the past it might be. Maybe he had buried some things so deep he had actually lost them for ever.

‘What do you want to be digging up all that old stuff for?’ he wanted to know. ‘It’s so long ago.’

‘That’s why I want to know,’ I persisted. ‘What harm can it do?’

‘You don’t want to be going over all that again,’ he muttered, ‘best to let sleeping dogs lie.’

‘I’ve been trying to piece together what happened,’ I went on, ‘and there are a few gaps that I need to fill in.’

I had refused to give up with the gentle interrogation, however much he evaded answering, and I doubted he would be accepting another dinner invitation from me for a long time. I pulled the pictures out again as the cabin crew went through their familiar rituals and the plane roared into life and lifted off from the runway. Despite the few things that Denis had reluctantly divulged, I was still having trouble getting a clear picture, which was why I had decided I had to make the trip back into the past for myself. I had to actually go to the streets where it had all started to see if they would jog my own memory, unlocking some of the doors in my head.

I had received the call from Patrick Dowling in Dublin two days before and had booked the flight immediately. He had been meticulously careful not to raise my hopes by making any promises, but I had grabbed at the straws he was holding out with all the desperation of a drowning man. He worked in some sort of public relations capacity for the Children’s Courts, and as a younger man he had also been a social worker in Dublin, so might know more about the sort of place that I had been kept for those early years. I felt sure the Court must have records from the time when I was born. Patrick was the best lead I had at the moment.

‘If you were to come in to see me next time you are in Dublin,’ he had said, ‘we could see what we can find out.’

I’m sure he was just being polite, hoping to put me off from what seemed to him like a lost cause. He certainly didn’t expect me to ring back a few hours later and tell him that I had booked my flight and would be with him in three days’ time.

‘I can’t promise anything …’ he’d said quickly, probably horrified to think he might not be able to help me after I had travelled all the way from New York to see him.

‘I understand,’ I assured him, ‘I’m just grateful that you are willing to help.’

I did understand how slim the chances of success were, and how little information I was going to be able to give him to go on, but that didn’t stop me from being ridiculously optimistic – and nervous.

I was aware that the Dublin taxi driver was watching me in his mirror and I tried to avoid his eyes, not wanting to be drawn into the conversation that he was obviously keen to have.

‘Can I ask,’ he said eventually, ignoring all the signals I must have been giving off, ‘do I hear an Irish or an American accent?’

‘Probably a mixture,’ I replied, giving up all hope of being able to remain alone with my thoughts for the duration of the ride from the airport into the city centre. ‘I’ve been living in New York for a long time, but I was born in Ireland.’

‘I thought as much,’ he crowed, obviously pleased with his own powers of perception. ‘You dress like a Yank, in your smart suit, and you have that American twang about your voice. But then I thought you must be Irish with those deep blue eyes and your looks.’

Believing that the ice had been broken between us he continued to chatter and I was able to drift in and out of the conversation as he pointed out local landmarks and buildings that he felt had probably arrived since I was last in the city. I could see there had been a lot of changes, but the essence of the city remained the same, with street after street of red-brick houses, every corner seeming to boast a pub. What surprised me was how small everything seemed after New York. The buildings had seemed so huge when I was a child, the roads so wide.

‘Is this your first time at the famous Shelbourne Hotel?’ he enquired.

‘Yes,’ I nodded and smiled at him in the mirror. It wasn’t completely true; I had been there before, more than fifty years ago. Although I had only been visiting for tea, it was an event that was etched deeply on my memory. It was the day when I first met Bill and realised that everything in my life was about to change and that nothing about my past was quite as I had believed it to be. I had never experienced anything like that tea before, and wouldn’t again for many years. It had been like arriving unexpectedly on a different planet.

‘Hello and welcome to the Shelbourne Hotel,’ the young receptionist beamed, ‘may I have your name, please, sir?’

‘Gordon Lewis,’ I replied, handing over a credit card.

She scanned her screen with well-practised speed. ‘Ah, yes, Mr Lewis, we have a nice suite for you, overlooking the park.’

I didn’t need a suite, but because I had booked at such short notice it had been all they could offer me. She signalled a bellboy to take my case up.

‘How long do you plan to stay with us, Mr Lewis?’ she continued as she typed.

‘It’s a little open-ended,’ I confessed, ‘I will know better in a few days.’

‘That’s fine, Mr Lewis,’ she said. ‘Enjoy your stay with us.’

I walked to the lift with the bellboy, looking forward to being alone behind a closed door with my thoughts. Once the bellboy had gone I pulled back the net curtains and stared out at the green of the trees opposite. Even though I had been living in the nicest parts of New York and other cities, the little boy in me was still impressed to find myself in the best hotel on the south side of the river in Dublin.

I had thought I would rest a little and then go out for a walk to acclimatise myself to the city of my birth, maybe find a noisy bar where I could lose myself in a dark corner and allow my mind to wander back over the years; but as the rain started tapping gently on the elegant old Georgian window I seized the excuse to stay where I was, turning on the television to watch the St Patrick’s Day parade. I would be spending plenty of time in the coming days pounding the streets and sitting in the bars as I tried to unearth the truth.

The next morning I rose early, too wired to sleep despite the time difference with New York. The rain had lifted and sun streamed into the room as I pulled back the curtains and ordered breakfast. An hour later I was down in reception, struggling with a map of the city.

‘Good morning, sir.’ I looked up to find a bellboy smiling at me. ‘Do you need any help? Do you know where you want to go?’

‘Yes,’ I said, a little too quickly. ‘I know where I’m going. Thanks all the same.’

I folded the map into my pocket and walked briskly out of the hotel, hoping that I looked like a man who knew where he was heading. I didn’t feel like sharing any information with anyone, however well-meaning they might be. The habit of secrecy was too ingrained for me to be able to shrug it off that easily after so many years. The boy’s accent had brought back unsettling memories. My friends and I must have sounded exactly like that when we were the little ‘unfortunates’, running wild on the streets of north Dublin. Anyone who comes from Dublin knows the difference between those from the ‘north side’ of the River Liffey and those from the more prosperous ‘south side’.

Once I was out of sight of the hotel I slowed down, my heart still thumping in my chest as I forced myself to stroll at a more leisurely pace towards the O’Connell Bridge with its ornate stone carvings and elegant Victorian street lanterns. I believe it is the only bridge in Europe that is as wide as it is long. Half-way across the bridge I stopped amid the bustle of people and traffic. Little had changed, except for me. Last time I had stood there, waiting with my mother for the meeting that was going to totally alter the course of my life, I had been too small to see over the side, peering through the stone balustrades and jumping impatiently up and down, wanting to get a better view of the detritus of the city as it drifted in the waters flowing under the bridge.

I leaned for a few moments on the rough stone which had then been taller than me and looked down at the flotsam and jetsam moving in the water below, the memories flooding my brain in a confusing montage of images and emotions which seemed more like half-remembered dreams, making my heart crash in my chest. Every direction I looked triggered more memories; the bridges, the buildings, the people. Every church spire seemed familiar, probably because I had been inside most of them at one time or another. Even the buses, which had been my first passport to the outside world, were parked in the same place on the embankment, or ‘Quays’, as they were known.

Now I might be able to stay in a hotel suite in the best hotel on the south side, but it was the north side that I came from; that was where my roots were, and that was where Patrick Dowling was waiting for me with whatever information he had managed to glean from the archives of half a century before. Breathing deeply, I steadied myself and continued on my way to my appointment at the old City Hall building where the children’s courts used to be, checking the map at every turn.

I felt like a small boy again as I announced myself to the receptionist and told her I had an appointment with Patrick Dowling. She made a call but hung up without saying anything.

‘He’s on the phone,’ she told me. ‘Take a seat and I’ll try again in a minute.’

As I sat staring at the sweeping metal staircase, not knowing what I was about to find out about my own past, my heart was thumping like it used to when I was a boy running wild around town in search of an adventure. It was like I was waiting for the curtain to rise on an eagerly anticipated new show. Every time someone came down I watched to see if they were likely to be looking for me, and after what seemed like an age a smartly dressed man with slightly wild grey hair descended and walked towards me with his hand extended.

‘Would you be Gordon Lewis?’ he asked with a friendly smile. ‘I’m Patrick Dowling. Welcome to Ireland. I hope it wasn’t too difficult to find us; we’re a bit tucked away from the other buildings in this area.’

He was tall and slim and I guessed he was in his forties, dressed in a dark two-piece suit, white shirt and tie, carrying a file in his other hand. He kept pushing strands of hair out of his face as he guided me towards a door on the ground floor, making polite conversation as he went, putting me at ease with typical Dublin humour.

Once inside the small room he closed the door and indicated for me to sit across the desk as he opened the file in front of him.

‘So, Gordon, you want to locate the home you lived in when you were a child?’

‘Yes,’ I nodded, hardly able to breathe in my anxiety to know what the file was going to reveal.

‘You would be amazed how many people like you come here looking for information about their past in Ireland. We do our best to keep records, but sometimes there are details which may be lost, or just not recorded.’

What was he saying? I felt a twinge of anxiety. Was he preparing me for disappointment? I nodded my understanding but couldn’t think of anything to say. After a moment he looked down at the file again.

‘A home for single mothers in Dublin in the 1950s, you say?’

‘Yes,’ I said, clearing my throat to stop the emotions from choking me. ‘My home, where my mother brought me up until the beginning of the sixties.’

‘The most infamous one, of course, was the Magdalene Laundries, where we now know that the girls and women were treated very badly, worked like slaves until they were old in order to atone for their sins. But those mothers weren’t allowed to keep their children. Usually the newborn babies were taken away for adoption or put into orphanages. But as I understand it, this didn’t happen to you?’

‘No.’ I didn’t trust my voice to say any more.

‘You were a lucky boy to have your mother to take care of you. Is there anything else you can remember about it?’

‘There were a lot of single women there, lots of us children too. Boys and girls. It was on the north side of the river and it was run by nuns.’ He was staring at me blankly as I racked my brains for more details. ‘I distinctly remember there was a mental hospital next door.’

He looked back down at his file for a moment. ‘There was a mental hospital in the area near this one.’ He pushed a map across the table and pointed to an area on the north side. ‘The institution was closed many years ago and the building is due for demolition. I don’t know what you’ll find if you go up there. The whole area is very run-down. It is bound to have changed a great deal since the fifties.’

He fell silent for a moment as I picked up the map and stared at it, trying to make sense of it, searching for names that might ring a bell, but to my confused eyes it just looked like a mess of lines and letters. Nothing made sense. I needed time to calm down and digest the information.

‘Does the name Morning Star Avenue, mean anything to you?’ he asked. I thought for a moment before shaking my head. ‘How about the Morning Star Hostel for Men? Or the Regina Coeli Hostel for Women?’

Regina Coeli. Was that a bell ringing somewhere at the back of my most distant memories? Or was it just that I wanted so much for something to sound familiar?

‘No,’ I said, ‘I don’t think so.’

‘I’m sorry we don’t have more details. There should have been files for every woman and every child in all these homes, but we had a burst water pipe about ten years ago and many files were ruined. All the names from that period were lost. I’m sorry that I can only give you so little to go on after you’ve come so far.’

At that moment I pictured myself going back to the hotel, picking up my stuff and catching the next flight back to New York, and the feeling of disappointment was overwhelming. I could see that Patrick was genuinely sorry not to be able to be of more help as he said goodbye at the door. I stood for a few moments on the pavement outside, not sure what to do next. I was still holding Patrick’s map. There didn’t seem any harm in at least going to look at the area he was talking about. Something there just might trigger my memories. I found Morning Star Avenue amid the jumble of print, worked out which direction I should be going in and set off.

It wasn’t long before the landscape began to change, all signs of the prosperity of the city centre gradually fading into areas of industrial wasteland. I don’t know how long I had been walking before I felt some vague stirrings of recognition. None of the street names rang a bell (though I wouldn’t have been able to read them when I was a boy anyway), but every now and then I saw a building or a view which I thought was familiar among the ruins and the occasional new developments. Then I would dismiss the idea again, telling myself I was imagining these things just because I wanted so much for them to be true.

Reaching the end of a long road I saw a large red-brick building, very different to everything that surrounded it. It looked imperial, like it had been a British headquarters of some sort. It seemed so familiar but no matter how hard I concentrated I couldn’t quite bring the memory into focus. The sound of loud voices caught my attention and I saw a group of people gathered on a litter-strewn piece of land further down the street. There seemed to be something familiar about them as well. As I drew closer I could see that they were men and women of different ages, but they were all drinking from bottles and I realised they had the same shabby, shambling look of the destitute, people who have ‘fallen through the net’ in society and ended up at this desolate roadside. Despite the bleakness of the scene, however, it felt strangely like home.

None of them gave me a second look. It was like I was an invisible ghost passing them by. I crossed over the road to the corner of the imperial-looking building and found a street sign announcing that I was standing in Morning Star Avenue. So was this the mental institution that I remembered? The one that Patrick said was due for demolition? Another street sign told me that the road would lead to a dead end. As I walked further along I noticed there was a slight slope, just enough to make my leg muscles ache, bringing back a memory of walking up a steep hill when I was a boy. Was this the same hill, turned into little more than a slope now that my legs were longer? I stopped and looked around at every view, desperately trying to recall distant pictures from the past.

I noticed grey railings along an overgrown garden to my right and a picture flashed up in my head. The narrow front garden had a statue of Our Lady Mary, the Virgin Mother, and on the wall beside a drainpipe a blue plaque announcing ‘Regina Coeli Hostel’. I felt a lurch of excitement in my chest. That was the name Patrick had given me which had rung a distant bell. Now that I was actually standing in front of it that bell was becoming clearer. This had to be the right place.

Behind the garden stood a long, two-storey, red-brick house. This was it – my first home! Regina Coeli was still standing after all these years. It was much smaller than the giant, rambling premises that I remembered as a small child, but now that I focused on it I could see details which reminded me of specific events. As I stared past the railings the memories came flooding back. I took my time looking around the garden at all the corners and spaces where I had played and hidden as a child, seeing them from a different perspective. Now the grounds which had seemed so enormous appeared quite modest. Something was missing. I concentrated hard and realised that next to the small house there should have been two huge wooden gates adjoining the building but they had gone. It didn’t matter. I was that little boy again. I had found my childhood home, the place which had seemed to me to be paradise, and now I would be able to unravel the rest of the story.