Читать книгу Secret Child - Andrew Crofts - Страница 6

Chapter Two Divine Intervention

ОглавлениеThe steady drizzle had soaked through Cathleen’s coat, making the bite of the cold wind even sharper as it stabbed at her fingers, which had locked painfully around the handle of the modest suitcase containing all the possessions she had in the world. Her feet were wet inside her shoes and the water was dripping down her face from her drenched headscarf and hair. The clouds had extinguished the last vestiges of light from the moon and no lights shone from any of the closed or abandoned buildings that loomed up around her.

Turning into Morning Star Avenue, every muscle in her body aching from the long walk and the heavy case, she saw a group of people huddling round a bonfire, swathed in layers of ragged clothes, their faces lit eerily by the flames licking up from the fiercely burning rubbish. They all seemed to be holding bottles in hands bandaged with layers of grubby mittens, swigging as they talked, trying to warm themselves from the inside as well as the outside. They all turned to stare at her as she walked towards them. Her heart was thumping in her ears. She had no experience of people like this, no way of gauging whether they would resent her straying into their area. Would they ask for money? She had none to give them. Would they attack her? There were too many of them and they would easily be able to overcome her. Should she turn and run? If she did that she would have to drop her case in order to stand any chance of escaping in her current state, and where would she run to anyway? This place was her last chance.

Holding her nerve she kept walking, trying not to look in their direction, trying not to look scared. She could hear the crackling of their fire as she drew closer, the sparks struggling up into the sky before being extinguished by the rain.

‘You looking for someone?’ a voice called out. It sounded angry.

‘You lost?’ another asked.

She turned and looked straight at them, facing up to her fear, telling herself that they were just people like her, currently down on their luck. ‘I’m looking for Regina Coeli,’ she replied.

They all laughed, as if they had guessed as much. They exchanged comments, which she couldn’t hear but guessed were lewd from the way they cackled and jeered at their own wit, apparently enjoying her discomfort.

‘Keep walking up the hill,’ a woman’s voice called out to her once the noise had subsided. ‘It’s the only house up there. You can’t miss it.’

One of the men made another comment and they all cackled again, turning their faces back to the warm, orange glow of the flames and the comfort of their bottles. Cathleen walked on into the darkness until a glow of a single lamppost appeared ahead of her. As she drew closer she saw a lone figure standing stock still beneath the light. She glanced back to see if any of the down-and-outs were following her, but everything was silent and black and wet.

Moving the suitcase to her other hand she took a deep breath and kept going towards the still figure. As she drew closer she realised the figure was a statue of the Virgin Mary, standing behind some railings in the front garden of a red-brick house that she guessed must be her destination.

‘You silly woman,’ she muttered to herself, relieved to have arrived but now nervous about the reception that might await her inside. She paused for a second, putting down the case and stroking her stomach, stretching the muscles in her shoulders and back, raising her face to the rain for a few seconds as she composed herself for the giant step she was about to take into the unknown.

She spotted a small door set into high wooden gates, with a bell beside it. As she reached up to ring it the gate opened and a woman appeared, throwing a heavy overcoat over her shoulders, her head down in preparation for walking in the rain. She almost bowled Cathleen over in her hurry.

‘Can I help you, ma’am?’ the woman asked. ‘Are you looking for somebody?’

‘Is this the Regina Coeli Hostel?’ Cathleen enquired.

‘Yes, come in,’ the woman said, retracing her steps through the doorway and leading her into the hallway of the house. ‘I’m Sister Kelly. Let’s get you out of that wet coat.’

Cathleen was aware that a puddle was forming around her on the stone floor as she shrugged off the coat and untied the scarf, attempting to mop some of the water from her blonde hair.

‘Take a seat, my dear,’ Sister Kelly said, glancing down at Cathleen’s belly. ‘I was just on the way home myself, so I will fetch Sister Peggy to take care of you.’

Cathleen sat on a wooden bench as Sister Kelly bustled out of the room, and took several deep breaths. The kindness of the older woman and the relief of taking the weight off her legs and back made her want to cry, but she held back the tears and composed herself for whatever was going to happen next.

A few minutes later a small woman in thick glasses and a big blue apron bustled into the room, carrying a worn piece of towel.

‘Oh, you poor thing,’ she exclaimed, ‘you’re wet through.’ She handed Cathleen the thin towel. ‘Dry your hair before you catch your death. I’m Sister Peggy.’

Sister Peggy watched for a moment as Cathleen attempted to dry her face and head a little. This was not the sort of girl she was used to seeing at the gates of Regina Coeli. To start with she was obviously older – Sister Peggy guessed she was probably in her mid thirties – whereas most of them were teenagers when they first arrived. Her clothes looked better than the others too. They were certainly not grand in any way, but even in their drenched state she could see that this was a woman who looked after herself and cared about her appearance.

‘Let’s get you through to the fire,’ Sister Peggy said. ‘What shall I call you?’

‘My name’s Cathleen Crea.’

When she stood up Sister Peggy could see that Cathleen was several inches taller than her and she guessed, from looking at her stomach, that she was about seven months pregnant. She led her through to a sitting room where a fire gave off a welcoming glow. Cathleen sat close to the grate and her wet feet began to steam gently in the warmth.

‘How are you feeling, my dear? Nervous, I dare say.’

Cathleen smiled, not trusting herself to speak in case she started to cry, afraid that if she let even one tear out she would not be able to stop the torrent.

‘You’ll be fine; you have nothing to fear here. We’re not going to be asking you any questions or making any judgements. You don’t even have to use your real name if you would prefer not to. You will simply be “Cathleen” to us, if that is what you would prefer. Let’s have a pot of tea.’

‘I want to keep the baby,’ Cathleen said once the tea had been brewed and she was beginning to thaw.

‘Sure, you do,’ Sister Peggy patted her hand reassuringly, ‘and so you will. Let me tell you a little bit about who we are. We’re all volunteers working here from the Legion of Mary. We like to be known as “Sisters”, but we’re not nuns. You won’t find any of us walking about in black.’ She gave a little chuckle at the thought. ‘We all understand and respect the need for privacy and anonymity. If you want to keep your child a secret from the world, that is fine. You can live here while you prepare for the birth without anyone else knowing, and you and the child can stay afterwards as part of the community. If you have a boy you can stay until he is fourteen. If it is a girl then you can stay a little longer.’

‘I have no money, Sister,’ Cathleen confessed.

‘I’m sure that’s right, my dear. Everyone here is in the same boat. Once you have had the baby we would ask you to pay for your board and lodgings by going out to work. The child can be looked after here while you are out and provided with one free meal every day.’

‘Who would take care of the child?’ Cathleen asked, hardly able to believe her luck at finding such a refuge from the storm.

‘Some of our single mothers do not go out to work, preferring to stay here during the day and look after their own children and those of the mothers who do go out to work. The working mothers pay the ones who care for their children from their wages.’

‘I see,’ Cathleen said, taking another sip of her tea and staring into the fire.

‘We do have a few rules,’ Sister Peggy went on. ‘There can be no pets, no alcohol and no men in the hostel or in the grounds. There can be no exceptions to those rules.’

‘I understand,’ Cathleen replied.

‘Shall I show you where you will be staying?’ Sister Peggy asked, putting down her cup and saucer. ‘Do you feel up to it?’

‘Yes.’ Cathleen stood up, despite her legs feeling a little wobbly, and followed Sister Peggy up a staircase.

‘Until the baby is born you will be staying upstairs in this house,’ Sister Peggy explained, opening a door into a large open dormitory. There were ten neatly made beds on each side of the room. Beside each of the twenty beds was a baby’s cot. ‘That is the only spare bed we have at the moment,’ she said, pointing to the furthest bed, ‘so that will be yours. The mothers are all having supper with their babies at the moment. In a few minutes they will all be coming up here and it won’t be so peaceful. Let me show you the facilities.’

They went back downstairs and Sister Peggy showed her the open washrooms with three bathtubs and four toilet cubicles. ‘All these walls could do with a lick of paint, for sure,’ she said, seeing the expression on Cathleen’s face as she looked around the shabby facilities, ‘but everything is spotlessly clean.’

‘It all looks just fine to me, Sister,’ Cathleen said quickly. The whole of Regina Coeli felt to her like a sign from God, as if he had heard her prayers and decided to give her and her baby a second chance. She certainly didn’t want to show even a hint of ingratitude in the face of such kindness.

‘Over there,’ Sister Peggy said, pointing through the window at a dark building across the grounds, ‘is where the older children and their mothers live. I’ll show you all around tomorrow, when it’s light. We just have a little bit of paperwork to do now, so let’s get that out of the way.’

Leading Cathleen into a tiny office space she handed her a form and a pen. ‘If you can just register here, then we can get you settled in and introduce you to the others. You don’t have to put your real name, just decide what you would like to be known as while you are with us.’

Cathleen stared at the form for a few moments before making a decision and carefully writing down the name ‘Kay McCrea’. This was a new name for a new life. Cathleen Crea had disappeared from sight in this new world. Now it was just Kay McCrea and her unborn baby starting again, safe, secure, hidden from the outside world and the baby’s existence a secret from everyone in her past life.

By the time she took her suitcase up to the dormitory all the other women were already there. Many of them seemed little more than children themselves as they chattered to one another, some of them bouncing babies on their hips while others were settling theirs down in their cots, trying to rock them to sleep despite the surrounding noise of voices and crying. Cathleen felt very grown up as she walked all the way down the middle of the room. None of them looked as if they had been taking care of themselves, their hair was lank and unwashed, and their pasty complexions in need of some healing rays of sunshine. Dark shadows ringed their tired eyes and none of them seemed to have the energy to smile. Cathleen felt almost maternal towards them. A few of them nodded to her as she made her way to her designated bed and she smiled in return, but none of them introduced themselves or spoke to her. She was happy with that, wanting nothing more than to lie down and sink into a deep, exhausted sleep.

She was pulled back to consciousness just before dawn by the cries of the first baby to stir and demand attention. One or two of the girls let out muffled curses as they tried to cling to sleep for as long as possible. Gradually they started up conversations as they lifted their babies out of their cots to feed them. Cathleen lay quiet, putting off the moment when she would have to talk to anyone.

‘Good morning, ladies,’ Sister Peggy said, moving through the dormitory to check that everyone was alright. ‘Have you all met Kay, who joined us last night?’

Cathleen pulled herself up, her bump making it an awkward manoeuvre, aware that all the girls were now looking in her direction, still without smiles, or even much interest.

‘I thought you might like a bit of a tour round the rest of the grounds this morning, Kay,’ Sister Peggy said, ‘to familiarise yourself with your new home.’

The other mothers were going about their business again, any vestige of curiosity they might have had about the newcomer apparently sated already. ‘That would be nice,’ Kay said. ‘Thank you.’

After joining in the bustle of washing and having some breakfast, Cathleen and Sister Peggy ventured out into the bright winter sunshine. Many of the younger children had already burst out of the confines of the buildings and were running around the damp grass as happily as in any school playground anywhere in the world.

‘This is Bridie,’ Sister Peggy said, taking her to a woman with sad eyes. She was dressed all in traditional black, reminding Cathleen of her own mother and aunts. Cathleen guessed she was probably in her forties, her dark hair peppered with grey. She was watching over a group of about five children. It was a relief to see someone closer to her own age. ‘She will be looking after your baby once you are ready to go out to work.’

‘Do you have a child here yourself?’ Cathleen asked, and the other woman’s sad eyes lit up.

‘My Joseph is five now,’ she said proudly. ‘He’s just started going to school.’

‘He’s a lovely boy,’ Sister Peggy said, ‘a credit to you, Bridie. You can be sure your baby will be in safe hands, Kay.’

Without knowing any more about Bridie, Cathleen knew instinctively that that was true.

‘Let me show you the chapel,’ Sister Peggy said, leading Cathleen back into the house and up to a door next to the dormitory where she had slept. ‘We have services on Sundays and Holy Days, which I hope you will join us for. The local priest leads them for us.’

Sister Peggy knelt down in front of the small altar, slowly crossed herself and whispered a prayer so quietly that Cathleen could not make out the words. After a few seconds she knelt down beside her, placed her palms together, lowered her head and closed her eyes. The two women remained there for several minutes, silently thanking the Lord for everything they had.

‘Now,’ Sister Peggy said, pulling herself to her feet, ‘let me show you the rest of the hostel.’

The buildings, which had once been a British army barracks, were set in three acres of grounds. There were several blocks of forbidding, three-storey, grey stone buildings. Some parts were depressingly run-down, with broken windows and missing doors.

‘It’s enormous,’ Cathleen said as they walked towards the first of the buildings.

‘So it is,’ Sister Peggy agreed. ‘We don’t fill every building, just a few of the more habitable floors. About a hundred and fifty women live here at any one time, usually with one child each. You will come across to one of these buildings once you are up and about after the birth.’

The wide open spaces on the inhabited floors had been turned into gigantic open dormitories, their stone walls and high ceilings blackened by smoke from the open fireplaces which burned Irish turf all day long and provided both warmth and basic cooking facilities, heating pans of water for washing and making tea. In these blocks there was only one toilet for every forty people, less if there was a blockage, and to make life easier many of the women kept their own enamel basins and chamber pots under their beds.

‘Do they have no privacy?’ Cathleen asked as she looked around.

‘You soon get used to it, my dear.’

Sister Peggy introduced her to a few of the women, but none of them seemed particularly interested, doggedly carrying on with their daily chores.

‘These are care mothers,’ Sister Peggy explained, ‘the ones like Bridie who are looking after the children for those who go out to work.’

Cathleen was relieved to think that it was going to be Bridie who was looking after her baby rather than any of these morose and silent girls.

‘What happens on the other side of the perimeter walls?’ Cathleen asked as they walked back to the red brick building.

‘You mean outside our prison walls?’ Sister Peggy said, her eyes twinkling mischievously. ‘There’s a wood mill over there. It’s more like a warehouse for the timber. The Dublin bus depot is over there. That,’ she said pointing to particularly dark and forbidding-looking building, ‘is part of the Grange Gorman Mental Institution. We call them “the crazy ones”, Lord bless their souls. The children are terrified of them. They think they’re going to escape over the walls and attack them.’

‘Oh,’ Cathleen couldn’t hide her own disquiet.

‘Don’t worry, my dear, they can’t get out. They’re locked up tight for their own good. Sometimes you will hear their screams in the night, poor creatures. You’ll get used to the sounds. Would you like to go back to the dormitory now and rest? You look a little tired.’

Cathleen was grateful for a chance to lie down and think about everything she had seen. However sweet Sister Peggy had been to her, and however grateful she was to find a refuge from the cold, wet streets of Dublin, the idea of bringing her child into such a place brought a chill to her heart. She racked her brain to try to come up with a better solution to her predicament, but could think of nothing. There was one person who might help, of course, but she could never ask that of him. At least here she had a bed and food and they would let her keep the baby. She told herself she must be grateful for such mercies and that she would find a way to get out once the baby was born and she had regained her strength. If all these young girls could bear to live here, then surely to God she could manage it too.

Over the next two months she threw herself into the routine of the hostel, never leaving the premises and making herself as useful as possible with the other mothers in the kitchen or in the dormitories, gradually making some sort of contact with those who were willing to talk to her and spending as much time as she could with Bridie.

One evening, when the two of them were sharing a well-earned cigarette by the fireplace, Cathleen confided some of her fears about the impending birth.

‘It’ll be fine,’ Bridie assured her. ‘Before long you’ll have a beautiful baby and that will make everything you’ve gone through worthwhile.’

‘I’m not so worried about the birth, it’s more the future that concerns me. I want so much more than this for my child and I don’t know if I will be able to provide it.’

‘Love the child, Kay, that’s all you have to do. Material things don’t matter. Children don’t know the difference between expensive clothes and cheap ones.’

‘In here they might not,’ Cathleen agreed, ‘but what about outside? There’s a big heartless world out there where people will judge my child for not knowing who his father is.’ Bridie reached over and squeezed her hand, not able to think of any words of comfort. ‘Your Joseph is such a lovely boy,’ Cathleen went on, ‘so kind and considerate with the other children, and so helpful to you. You’ve brought him up well. Thank God it’s going to be you looking after my child.’ Bridie gave her friend’s hand another squeeze, embarrassed by the praise.

Most of the other girls paid Cathleen little attention but there was one, Bridget Murphy, who seemed to have taken an instant dislike to her. Bridget was a big, fat bully of a woman who seemed to see Cathleen as some sort of challenge to her authority. Cathleen had seen her reducing one of the youngest girls to tears.

‘Empty my piss pot,’ Murphy had instructed the girl.

‘Empty your own piss pot,’ the girl retorted, her bravado undermined by the tremble in her voice.

‘Empty my piss pot you fucking whore,’ Murphy screamed as the girl scuttled tearfully from the room. Everyone else averted their eyes, not wanting to attract Murphy’s vitriol onto them.

‘And you …’ Murphy screamed at Cathleen. ‘You need to watch yourself around here with all your airs and graces. Who do you think you are? Think you’re too good for the rest of us, you do.’

Cathleen didn’t respond, and from then on Murphy referred to her as ‘the Lady’, a nickname that the others also started to use for her, but as a show of respect rather than a term of abuse.

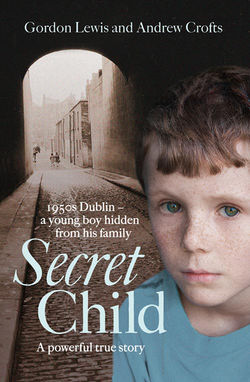

On 25 February 1953, Cathleen gave birth to Francis Gordon – that’s me – her secret child, and my life at Regina Coeli was under way.