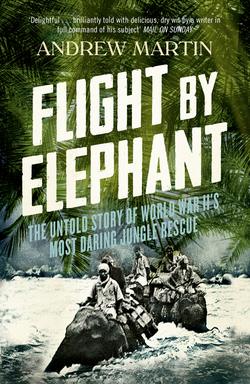

Читать книгу Flight By Elephant: The Untold Story of World War II’s Most Daring Jungle Rescue - Andrew Martin - Страница 8

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеIn the monsoon season of 1942, deep in the jungles of the Indo-Burmese border, Captain Reg Wilson wrote of our principal, Gyles Mackrell, that he ‘knew what an E. could do’. An ‘E’ was an elephant.

Mackrell knew how to manage elephants as beasts of burden; he also knew how to kill an elephant with a single bullet if – and only if – it had gone rogue. He knew how to manage the elephant riders, or mahouts, who were known to be stroppy, a tendency exacerbated in many cases by a bad opium habit. If a cane and rope suspension bridge had been washed away by a swollen river, Mackrell knew whether it might be possible to cross that river on the back of an elephant; he knew which of any given herd of elephants might be best suited by strength and temperament to attempt the feat, and whether it might be best accomplished by the elephant swimming or wading. He would be perfectly willing to climb aboard the elephant himself rather than leave the job to the mahouts because he was a man who not only enjoyed a physical challenge, he also seemed to live for risk taking.

Gyles Mackrell went to the sort of minor English public school where the sinks had two cold taps, where a lecture on the Benin Massacre was classed as ‘entertainment’, where visiting military men donated leopard skins and trophy animal heads for the adornment of the library rather than books, and where the pedagogical aim was to produce young men capable of assuming the white man’s burden. It was not an intellectual environment and Mackrell was certainly no intellectual. In an age when ‘bottom of the class’ was an official status (since the rankings were published every term) Mackrell repeatedly occupied that very position. Yet he had great practical intelligence, and the diaries disclose an elegant, spare writing style. He was not the all-purpose ‘hearty’: he does not seem to have featured in any of the first, second, or even third elevens; his school did not make him one of those Edwardian boors with a caddish moustache and a racist turn of phrase, but in his late teens he did have a hankering after a life of adventure, and the British Empire was there to provide it. So Gyles Mackrell became a tea planter in Assam, India.

Unlike Australia or Canada, British India was not a colony in the literal sense. Its only settlers were the tea planters. In order to create their plantations they had to clear the jungle, but the jungle kept coming back. The tiger wandering through the living room of the bungalow was not an unknown sight to the Assamese planters and their wives, who wore galoshes in their flower gardens against snake bites. Elephants, when they were behaving, were the planters’ allies in the animal kingdom, whether they were used for uprooting trees – which an elephant does by leaning casually on the tree – or for carrying cargo, or simply as a runabout: a means of getting the planter to his club for the six o’clock whisky and soda. A late nineteenth-century manual for aspirant tea planters describes the elephant as ‘the most useful brute in Asia’.

Before the First World War, the planters’ main enemy was Mother Nature. Their military involvement had been confined to membership of picturesque part-time cavalry regiments which, in between mess lunches and polo tournaments, mounted occasional expeditions against troublesome local tribes. The First World War did not touch the tea planters of Assam directly, although many of them volunteered to fight in Europe or the Middle East. Gyles Mackrell himself chose the almost suicidal option of becoming a fighter pilot on the Western Front with the Royal Flying Corps, a job carrying an average life expectancy shorter even than the six weeks an infantry officer could bargain for. Later in the war he was posted to conduct what were mainly surveillance operations against the rebellious Muslim tribes on the North-Western Frontier. In the flimsy death-trap planes of the time, Squadron Leader Mackrell, as he had now become, patrolled the skies over Waziristan in temperatures of 120 degrees Fahrenheit. At any one time more than half the flyers engaged on such missions were sick, which is not to say that the peril was not greater for the tribesmen beneath, who were sometimes bombed in their mud huts.

The volatile North-West Frontier was regarded as the Achilles heel of British India throughout the First World War, but, in the Second World War, the North-Eastern Frontier also became vulnerable as a result of the Japanese invasion of Burma. In the first half of 1942, the Japanese squeezed the British out of Burma like toothpaste from a tube, starting from the bottom. Tens of thousands of British soldiers, administrators and businessmen, and the million-strong retinue of Indian and Anglo-Indian servants and workers who had buttressed British rule in Burma, were harried into Upper Burma, from where they attempted to flee to the safety of Assam. They had no choice but to do so by walking through mountainous and malarial jungle in monsoon rain.

So the war came to the tea planters in the form of a tide of refugees. In response the planters mounted – their critics would say they were prevailed upon to mount – a relief effort. In conjunction with their wives, and their own Indian servants and workers, they deployed their logistical skills (the planters were great ‘organization men’), their medical supplies, their stores of food, their tractors, lorries, horses, ponies and elephants to assist what was called ‘the walkout’. The planters built roads and established staging posts in the jungles for the refugees to be given medical treatment, food and, above all, tea. The first sign of these camps to the starving refugees staggering in from Burma was a stall in the jungle from which tea and biscuits were being dispensed; tea would be kept brewing throughout their brief stay at these camps, one of which was officially called the ‘Tea Pot Pub’.

Tea is the British panacea and cure-all, and it is fondly suggested that our response to any disaster is ‘put the kettle on’. Here was the same reflex action on a huge scale, the disaster being the unprecedented collapse of a prop of the British Empire, triggering death by disease or starvation for hundreds of thousands.

What follows is the story of an episode within that epic disaster. It focuses on the most obscure and also the most treacherous of the evacuation routes from Burma. Before 1942 the number of Europeans who had followed that route could have been counted in single figures, and most of them were eccentrics with a taste for reckless action. None, however, were so mad as to attempt the feat in the monsoon season.

The hero of the story is probably the above-mentioned Mackrell. In 1942, he was fifty-three. In British India professional lives were foreshortened by the climate and the physical demands of the life. When a man reached his fifties, it was time to think of returning home, ideally to some coastal town – Eastbourne in Sussex was a popular choice – where bracing air would provide a corrective to years of stifling humidity. For Gyles Mackrell, fighter pilot, big game hunter, jungle wallah, the relief operation mounted by the Indian Tea Association provided a last chance to live life as he had grown addicted to living it: dangerously. The beauty of the situation to him was that, if he could take elephants and boats deeper ‘into the blue’ than they had ever been taken before, he would have the reward of saving lives.

But the crisis brought out the best in other people as well, and the characters of the drama are presented as an ensemble cast. They are, in the main, middle-class British men, and they were often accompanied by Indian servants or received other assistance from the indigenous peoples, and to these two groups must go a great deal of the credit for such successes as the white men achieved, as Gyles Mackrell and most of the other principals pointed out. In particular Gurkha soldiers gave assistance, playing their habitual role of rescuing the British from messes of their own making. But it is the white men who kept the diaries, and they are therefore in the foreground of our story, which begins not with Mackrell and his elephants, but with two men for whom some elephants would have been very useful indeed.