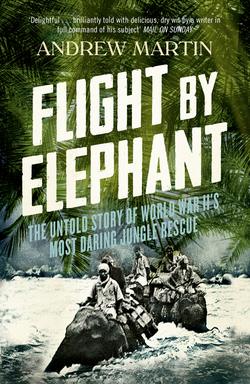

Читать книгу Flight By Elephant: The Untold Story of World War II’s Most Daring Jungle Rescue - Andrew Martin - Страница 9

Millar and Leyden: The Men Without Elephants

ОглавлениеOn 19 May 1942 two Englishmen, Guy Millar and John Leyden, entered the Chaukan Pass in Upper Burma with the aim of reaching civilization in Assam, India. The pass – a vaguely defined groove through mountainous sub-tropical jungle, with fast-flowing rivers coming in from left and right – was either unmarked on most maps or dishearteningly stamped ‘unsurveyed’.

Millar and Leyden did not want to be in the Chaukan Pass, but they had no choice.

John Leyden himself had been overheard describing the pass route as ‘suicidal’ shortly before he set off along it. We know that Millar, who was keeping a diary as he entered the pass, was uneasily aware that very few Europeans had ever been through it before, and he seemed to recall that fatalities had usually been involved.

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, a few European parties had been through the Chaukan: Errol Gray, an elephant expert resident in Assam, had done it, as had a certain Pritchard, whom nobody knows much about. Prince Henri of Orleans also traversed the pass in that decade, but then here was a man whose life seems marked by a determination to get himself killed. (Henri of Orleans discovered the source of the Irrawaddy river in 1893, earning himself a gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society in London, despite his being, as the Encyclopaedia Britannica of 1911 puts it, ‘a somewhat violent Anglophobe’. In fact, he was somewhat violent full stop, and in 1897 he wounded, and was himself wounded by, the Comte de Turin in a duel.) All the above were accompanied by numerous elephants and porters.

In 1892, a quite well-known double act of English exploration, Woodthorpe and MacGregor – that is, Colonel R. G. Woodthorpe, a surveyor in the Royal Engineers, and Major C. R. MacGregor of the Gurkha Light Infantry – went from Assam to Burma and back through the Chaukan. But, then, they were accompanied by two fellow officer of the British Indian Army, forty-five Gurkhas, twenty-five men of the Indian Frontier Police ‘together with’ – as Major MacGregor airily informed the Royal Geographical Society on his return – ‘the usual complement of native surveyors, coolies, & c’. They also had with them a great builder of bamboo bridges and rafts (in the person of Colonel Woodthorpe himself), together with something called a ‘Berthon’s collapsible boat’ – the collapsing and uncollapsing of which caused wonderment among the tribes they encountered – and ‘some’ elephants, the number of which MacGregor does not specify.

The rule of thumb in Upper Burma and Assam in 1942 was that a human porter carrying 50lbs of rice through the jungle must himself consume a minimum of 2lbs of that rice every day. An elephant, by contrast, can carry only 600lbs of food on its back and doesn’t need to eat any of it, since it eats the jungle as it goes. Alternatively, an elephant can carry six large men on its back, together with its human assistant, the mahout (who is usually very small). An elephant’s normal marching speed is six miles an hour, twice as fast as a man. With men on board, elephants can climb steep embankments – which they usually do on their knees. They can also carry men across fast-flowing rivers, and this is where the elephant really comes into its own on the Assam–Burma border: as a portable bridge. This is a territory where rivers are the problem and elephants are the answer.

But Millar and Leyden didn’t have any elephants with them. Instead, they had an elephant tracker, a young Assamese man called Goal Miri (Miri denotes his tribe) who was skilled at finding and following the tracks that wild elephants made through the jungles, and was retained by Millar as his personal servant. They also had a dozen porters recruited from the Kachin, one of the Upper Burmese tribes more sympathetic to the British, and Leyden’s spaniel bitch, Misa, who was pregnant.

Millar and Leyden had set off from Upper Burma on 17 May with enough rice, potatoes, onions, sugar, condensed milk and – being British – tea for fourteen days. They had to reach India before their supplies ran out because the jungle could not be guaranteed to yield up any food, and the country along their route was uninhabited. They were aiming for the Dapha river. Only when they reached it would they know they were on target for the plain of Assam, but they also knew that when they did reach the Dapha they would have to cross it. This wasn’t going to be easy. In 1892, Errol Gray had pronounced the Dapha ‘not fordable after early March’ on account of the meltwaters of the Himalayas. On top of that, Millar and Leyden were approaching the Dapha in the monsoon season, the rains having started about a week before they entered the pass. All previous expeditions through the Chaukan had taken place in the cold weather season – in December and January – when the many rivers are singing but not roaring.

On the morning of that first day, 19 May, Millar and Leyden crossed a relatively small but meandering river called the Nam Yak. They then crossed it a further seventeen times, each encounter preceded by the depressing sound of its rising roar coming from beyond the trees. They would half wade, half swim over the river. The water was chest-high for Millar and Leyden, but higher for the Kachins, most of whom were about five feet tall – one of the pygmy tribes, as the early British settlers in Burma would have referred to them.

After three days, Millar and Leyden emerged from the Chaukan Pass, but the mountainous jungle continued. In fact, as Millar noted in his diary, ‘the going became still more difficult’. They were descending only slowly from a height of about 8000 feet. They proceeded, slashing with their kukris (or large, curved knives) along the elephant tracks Goal Miri had identified, which at first, or even second, glance didn’t look like tracks at all. Or they would follow the banks of the rivers. Hitherto, these had tended to go across their direction of travel, but when they came out of the pass, Millar and Leyden struck a river that was going their way – that is, west. It was called the Noa Dehing.

They couldn’t cross the Noa Dehing, which was about 400 yards wide, and sunk in a deep, jungly gorge. They couldn’t even see across it, steaming rain having reduced the visibility to almost nil. They were therefore stuck on the right-hand bank – and this confirmed their appointment with the Dapha, which was a tributary of the Noa Dehing shortly to come thundering in from the right. Meanwhile, it was usually better to follow the bank of the Noa Dehing than hack away at the jungle.

So Millar and Leyden walked along the stones at the water’s edge – when there was an edge to the water – as opposed to a vertical wall of red mud. Some of these stones, Millar wrote, were about the size and shape of a cricket ball, and threatened to twist your ankle. Others were about the size and shape of a small house, so Millar and Leyden would climb up, across and down, often descending into deep pools, so that the leather of their boots began to rot. When the vertical mud wall was the only option, they proceeded monkey-like, holding onto the roots of trees or stout bamboos. It is unlikely that they talked much as they climbed. Their voices would have been drowned out by the crashing past of the river; and a malnourished man finds it hard to talk. It becomes a labour to formulate the thoughts and pronounce the words.

The rain made it hard to light the fires they needed at night to boil up their rice. They had to search the undergrowth for dry bamboo, which they cut into slivers to make kindling. This they then tried to ignite, but the Lion Safety Matches of India and Burma were considered by many of their users all too safe: the sulphur tended to drop off the end when they were struck, or they would break in half.

When bamboo does burn, it makes a mellow bubbling, popping sound. Every night after they’d eaten their rice, Millar and Leyden made tea: Assam leaves swirling in a brew tin full of river water. G. D. L. Millar was a tea planter from Assam – manager of the Kacharigaon Tea Company – and never let it be said of the British tea planters of India that they did not consume their own product.

On one those early evenings by the fire, Leyden took a photograph of Millar; it shows a tough forty-two-year-old, unshaven, standing in front of a bamboo fire. The porters crouch around him Burmese-style, like close fielders around a batsman; he wears loose fatigues and the manner in which he holds his cigarette is slightly rakish. Millar was christened Guy Daisy. In the Edwardian days of his birth, Daisy could be a boy’s name; it might be further explained in Millar’s case by the fact that he was born on a farm in Cornwall. Daisy means nothing more incriminating than ‘the day’s eye’ and you might think it would suit an outdoorsman. But Millar made that ‘D’ stand for Denny.

He was on a three-month release from the Kacharigaon Tea Company in order to do ‘government work’ in Upper Burma (and we shall come to the question of what that had involved) in the company of Goal Miri and a cranky sixty-four-year-old botanist called Frank Kingdon-Ward.

Before coming to Millar’s companion, Leyden, a word about that cigarette of Millar’s. How had he kept it dry when crossing all these rivers in monsoon rains? There will be a lot of cigarettes in this story, a lot of rivers and a lot of rain, so it is a question worth asking.

The cigarettes of the day usually came in cylindrical tins about two and a half inches in diameter. The tins were sealed below the lid. A small, levered blade was set into the lid; you pressed it down and rotated the lid in order to break the seal. Until then, the tin was entirely waterproof, and it was still fairly waterproof afterwards. The tins, which contained fifty cigarettes, were too big to put in a normal pocket, so most people decanted them into a slim cigarette case – but cigarette cases were for the drawing room, and in the jungle Millar smoked his straight from the tin.

Millar’s travelling companion, John Leyden, was a civil servant of British Burma, a colonial administrator. He could be loosely referred to as a DC, or Deputy Commissioner. More correctly, he was a sub-divisional officer of the North Burmese district of Myitkyina where, according to Thacker’s Indian Directory, the languages spoken included Burmese, Kachin, Hindustani, Lisu, Gurkhali and Chinese. Myitkyina was the last decent-sized town in Burma; the railway ended there, but a dusty mule track snaked north from the town, through a mosquito-infested jungle and scrub unfrequented by Europeans apart from the odd orchid collector. The path winds towards a small settlement of green and red houses perched on top of a treeless green hill, like a place in a fairy story. This was Sumprabum, the centre of Leyden’s particular sub-division. (And while we are in this remote vicinity, let us note an even narrower track winding down the hill and meandering still further north to an even smaller, even more malarial settlement called Putao.)

John Lamb Leyden was born into a distinguished Scottish family, and was a descendant of another orientalist, John Leyden (1775–1811), poet, physician and antiquary, who ran the Madras General Hospital and held various official posts in Calcutta. Ominously for John Lamb Leyden, his ancestor died of fever on an expedition to Java.

We have a photograph of John Lamb Leyden on his trek – probably taken by Millar after Leyden had taken his. It shows a cerebral looking man with swept-back, receding hair. At thirty-eight, Leyden was younger than Millar, but looked older. Next to him, a bamboo fire smoulders thickly. He and Millar would light these at every camp, hoping the smoke would attract the planes that periodically flew overhead, but as Millar wrote, ‘… on each occasion failure to observe us was apparent’. They had no tents, so every evening they spent a couple of hours building a hut of the type known locally as a basha.

How do you build a basha?

In a lecture entitled ‘Keeping Fit in the Jungle’, given to the Bengal Club of Calcutta in early 1943, Captain Alastair Tainsh explained:

The way to keep fit in the jungle is exactly the same as anywhere else. All one needs is sound sleep, clean water, a reasonable diet, and a liberal use of soap and water. But how is sound sleep to be obtained? Well, one must learn how to make oneself comfortable in the worst conditions. It is not being tough or clever to sit in the open all night … The easiest form of shelter to build is made by fixing two upright poles in the ground eight or nine feet apart. To the top of these is bound a long bamboo making a frame like goal posts. The roof is made by leaning a number of poles against the top bar forming an angle of about 45 degrees with the ground. A number of parallel bamboos are tied to the sloping poles and into this framework banana or junput leaves are thatched.

Then you had to build a chung, or sleeping platform, to keep the leeches off, and sometimes Millar and Leyden couldn’t be bothered to do any of this, so they’d sleep in the crooks of trees. They always kept a fire burning in case a tiger should turn up, although as Millar wrote, about a week into their trek: ‘… this stretch of country is uninhabited for over a hundred miles. Not only is there not a trace of man, but mammal and even bird life is conspicuous by its absence; truly a forgotten world, where solitude reigns supreme.’

Here, too, we can invoke the voice of reason himself, Captain Tainsh:

Nearly everyone is a little frightened when they hear they must work and live in the jungle. The word ‘jungle’ conjures up in their minds a place literally swarming with lions, tigers, elephants and snakes. Nothing could be further from the truth, because wild animals and even snakes need food, and such wild animals as there are, live on the edge of cultivation, and are seldom seen in the thicker parts of the forest.

The larger animals are particularly scarce in the monsoon, when they retreat to the margins of the jungle, to avoid the leeches and mosquitoes that proliferate in the rains. Against these torments, Millar and Leyden slept with their heads wrapped in blankets but still Millar wrote, ‘Of the leeches, blister flies and sandflies I cannot give adequate description, sufficient it is to say that we were getting into a mess.’ For most of the nights, they didn’t sleep at all, but just listened to the sound of rain drumming on palms or bamboo. In the morning, the rising heat of the day made clouds of steam rise up from the muddy jungle floor like smoke from a bonfire.

By 26 May, with nine of their fourteen days of food gone, there was no sign of the Dapha river, and Millar and Leyden were down to one cigarette tin of rice per man per day.

Why had these men entered the Chaukan Pass?

To escape something worse coming from behind.