Читать книгу Moving - Andy Hargreaves - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Step by Step

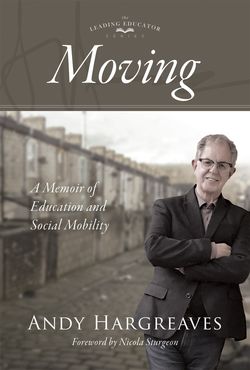

ОглавлениеAcross the span of almost seven decades, I’ve made what feels like a huge change. I’ve moved from a two-up, two-down rented terraced house with no indoor toilet, on a cobbled street, in an old Victorian mill town, to being a reasonably well-known (some would even say quite famous) professor, writer, speaker, and government adviser in my field of education. These days, almost every month, I meet with a minister, president, ambassador, or other dignitary, at his or her request. I’ve lived and worked in three countries and, with my family, become a citizen of two. That’s a lot of movement.

But big changes in life circumstances usually come through smaller increments, the many tiny steps that define social mobility. This book covers the first two decades of my life with my family, in my community, and at school and university, and it is about these less grandiose but equally important changes. It is about moving in the mid-1950s, with the support of the welfare state, up the hill on the back of a coal truck and into public housing—and then, with a bit of good fortune, into a small owner-occupied terraced home. It’s about moving up from infant school—known in North America as kindergarten and first grade—to junior school, from being with the whole range of children in my neighbourhood to just the ones who were selected for the A stream. It’s about moving on, to join the 15–20 per cent or so of my age group who went to grammar school, and travelling across town to get there, from one side to the other. It’s about walking there and back, a mile each way, four times a day (though not uphill both ways!), with an ever-shrinking group of fellow students who stayed on beyond the minimum leaving age. Then it’s about moving away, off to university, as many like me did, and never truly going back.

Social mobility lifts some people up. Others are left out or get left behind. They include my two brothers, who didn’t pass the test that would have got them to grammar school and who therefore weren’t allowed to learn the things they wanted—history, art, music, and sport. Rather than going to university on the other side of the country, they ended up in factories at the bottom of the hill. The left-behind also include the kids who were down in the primary school B stream, who went to secondary modern or vocational schools, who left school early and mostly worked in their overalls while we went to school in our uniforms. They were also the kids who picked out and picked on the “snobs” and the “swots” like me, who had been arbitrarily elevated above them from the age of seven, with insults and fights—breaking my brother’s violin and giving me a black eye for my trouble. Social mobility is a process of exclusion as well as inclusion. At the same moment some are able to step up, others discover they are falling more and more steps behind.