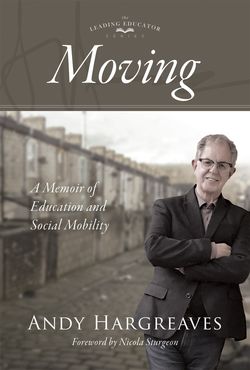

Читать книгу Moving - Andy Hargreaves - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Leave or Remain

ОглавлениеSo once you move up and out from your class and community, what is it that changes about you, and what stays the same? When you come home from university, or a plum job in a new city, or back from another country altogether, do your family and friends rejoice in saying, “You haven’t changed a bit!”? Or do you let it all go to your head and put your past behind you? How do you reach for the stars yet keep your feet planted firmly on the ground?

Uruguay’s superstar football player—soccer player in U.S. terms—Edinson Cavani puts it this way. In a letter to his nine-year-old self, Cavani tells him he will fulfil his dreams of making lots of money, driving nice cars, and sleeping in fancy hotels.24 But the constant travel will take its toll, he warns, and he will not always be happy. So he urges his younger self to always remember:

You live your life outside, with a ball at your feet. This is the way in South America. You don’t know anything different. What’s inside, anyway? Nothing fun. Nothing interesting. No Playstation. No big television. You don’t even have a hot shower. There’s no heat…. When you want to have a bath, you get a water jug and heat it up over the kerosene stove.25

Cavani insists that wherever he’s playing in the future—a vast stadium, a big cup final—his younger self should always find a way to “feel the dirt under [his] bare feet.”26

There’s no dirt under the feet for me, even though, in my childhood, I did have my baths in a metal tub in front of the coal fire. But there was and is the millstone grit on the peat-bog moors, high above the chimney tops of my upbringing. The grit is what I walked across, mile after mile, with my big brother after my dad had died. It’s what our stone terraced houses and the cobblestones of our streets were fashioned from. It’s what my playmates and I knelt on in our short pants when we rolled coloured glass marbles and steel ball bearings down stone slabs in the schoolyard. And, if you’re lucky, it’s what remains in your character that becomes part of the landscape of your soul wherever you find yourself in the future. This is not just Angela Duckworth’s grit—the grit of sheer perseverance or tenacity in response to daily adversity.27 It’s also the grit of defiance in the face of obstructive and oppressive authority.

As you move up, on, and out, you hope you hang on to some of these things. You hope you’ll continue to stand up to and stand with others against injustice and exclusion. Despite all your travels across different countries and cultures, you hope that when you open your mouth, people will still be able to tell where you come from. You hope you’ll retain some of your interests and TV-viewing habits, however unsophisticated and unfashionable they may be amongst the intellectual elite. You hope you’ll remember to treat all people with respect and dignity and acknowledge their humanity by thanking and conversing with them—the driver who lets you off the bus, the waiting staff at a conference dinner who never get noticed or receive any tips, and the people cleaning the toilets in the train station or the airport—because you remember how your mum used to clean people’s houses and how, when your own children were small and you were struggling financially, your wife was a waitress in the local pub and sold Avon cosmetics door-to-door in the evening. You also hope you do all this simply because it’s the decent thing to do.

But you also know you are moving in different circles now. Your accent will change a bit as you go from place to place. The subjects of the conversation will shift and widen—and why shouldn’t they, for don’t these worlds of literature or opera or international travel open your mind to other people’s perspectives? Isn’t this what your education was for? After all, one Latin root of education is from educere, meaning “to lead out.” But you’ll also feel uneasy when comfortable elites are smug or patronizing, when they search for a weak spot in your knowledge, your manners, or your bearing so they can put you back in your place.

Will you rebel? Will you stand up for yourself and others who are being slighted? Will you hold your tongue to keep the peace? Or will you respond with rapier-like flashes of cutting wit? Perhaps, like Drake, you’ll accomplish even more success just to show them a thing or two at thousands of dollars a show. Sometimes, like former U.S. ice skater Tonya Harding, when the judging is stacked against you because you like to do the equivalent of skating to rock and roll, not to orchestral classics, you also know you’ll just have to pull off your own unanswerable equivalent of a triple axel so they can’t, for shame, hold you back any more.28 Whatever the question, you’ll ultimately have to answer with your work.

But what will you say when you go back home and the family you love makes racist remarks or sexist jokes? What will you do then? Who will you be? How will you take advantage of every opportunity that has come to you, including that of an open mind, yet also keep the ball at your feet and the grit between your teeth?

There’ll be no balanced life for you—not for many years, at least—for this aspiration belongs only to the privileged. They already have something to balance. You’ll work relentlessly hard, knowing that on the ladder of upward mobility the rungs beneath you never stop falling away.

Social mobility is neither unambiguously heroic nor inescapably tragic. The path of social mobility, the process of moving on up, has complications—for everybody. This book is about my own path and the paths of others. If you are mobile, have been mobile, aspire to be mobile, or can influence others in their own efforts to be mobile, it’s a book that might have something to say to you.