Читать книгу Bittersweet: A Memoir - Angus Kennedy - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface

Okay, I’m not into long lists of thank-yous extended to people neither of us would care to meet.

However, there is one person I should mention: the anesthetist who yesterday put me to sleep for an operation to remove a cyst on my left knee. Yes, he deserves to be on my list of honors. Wow, those anesthetics are amazing. I mean, what is that drug they give you before the one that makes you sleep? You know, the one that says, Hey, Angus, it doesn’t matter if they chop off your entire leg or if chocolate runs out forever—nothing matters!

Just looking into the anesthetist’s face, fully equipped with one dark eyebrow with the curious ability to move on its own, while the other, a light-colored one, remained stationary, was a good start. Watching this facial performance while he proceeded to proudly name all the drugs he was administering as my consciousness drifted into the ether: now that was pretty damned cool.

Angus Kennedy you’re going down.

It was a general anesthetic of course, and I fell asleep the moment I started to lie back and felt the nurse’s hands guide my head. The operation was, I say, almost a success. They found not one, but three “foreign bodies,” which they presented to me in a small blue pot when I woke up (now sent off for analysis), floating around the soft tissues at the back of my knee. Four years of pain are now almost over.

I think I am high from yesterday’s drugs. I must be, and because of that and not being able to stand up, I am here now finishing this book on the couch with a single origin bar of French chocolate handy. (That is also keeping me on the couch!) So we should all thank him, and chocolate of course, and not a boring list of lifeless aunties and distant acquaintances.

I’m a man with five kids, an impossibly busy job in confectionery conferencing and magazines, and never enough time even to escape to the bathroom in the mornings before I have to perform the most intolerable school runs ever in a ten-year-old Land Cruiser. So how was I ever going write a book—another book, even, I asked myself? But once I started, I knew it would be okay. You can’t leave off books when you write them. They’re like plants; they need feeding or they die.

So now I am back home, sitting in the living room over the school holidays with my knee up and trying (rather foolishly) to concentrate with an Xbox on in the background and three overactive boys shooting anything they see on the screen. At last I have the chance—the book I have been meaning to finish will be finished, thanks to my wife, Sophie, now with a drugged-up cripple on the couch during Easter, who at every juncture is being asked, “What can I do now, Mum? I’m bored.”

Ah, Easter: a period in which we in the United Kingdom spend about £2,462 million on chocolate, which translates into 70,000 tons of it, according to the International Cocoa Organization. Not much when the world munches through 7.6 million tons a year. Yes, a celebration during which British kids, on average, consume 8.8 chocolate eggs each; each egg averages about 750 calories. That’s 6,600 calories, enough for each child to run from London to Oxford without stopping.

So I confess: my world—and the act of feeding my family—rely on chocolate. I have made a living out of “loving” a product that can rot your teeth, make you fat, take control, and see us all coming helplessly back for more. It’s time not just for me to make a few personal confessions, but at last, it’s confession time for the whole industry. And my first confession is one of the most difficult for many to swallow.

Introduction

Welcome to my job. I confess: I get paid to eat and write about chocolate and candy each and every day that I am still alive. The best job ever, some say.

And welcome to my world: chocolate, a substance that contains nearly the highest calorie content of any food and is one of the most addictive, too. A hefty 90 percent of American citizens vote it as their favorite flavor, while according to recent research by Fererro, 43 percent of Brits would give up booze for it, 35 percent religion, 27 percent would never wear their favorite pair of shoes again, and 9 percent admit they would give up sex for chocolate.

So, the basic truth is that I fly around the world visiting chocolate factories and sampling their confections directly from conveyor belts for my articles and various media assignments. When I am not in factories eating these goodies, extra chocolates and candies are delivered almost daily onto my office desk with ever more creative deliveries. That’s nuts, right?

I even have a chocolate coffee table in my office. It was presented to me as a gift after a global chocolate convention. It’s mostly eaten now, mainly because I enjoy the occasional snap as I break off pieces and consume my table in front of my guests. Chocolate sculpture is a big thing now, especially in Paris, where the competitions last for days on end. You can hardly tell these things are made out of chocolate; they make anything from shoes to famous faces to entire landscapes, detailed with edible spray paint. It’s all a bit ridiculous if you really think about it.

There are people out there who love chocolate far more than I do and deserve to have it more than I do. But life isn’t like that. Anyone who believes life is fair is very lucky.

I didn’t plan or really deserve the dream job of being Britain’s chief chocolate taster. But it seems to have to be this way. Besides, we don’t apply for the best jobs in the world, we create them. We always create the most enjoyable things. We never seem to work for them. How can anything be enjoyable if we have to work for it anyway?

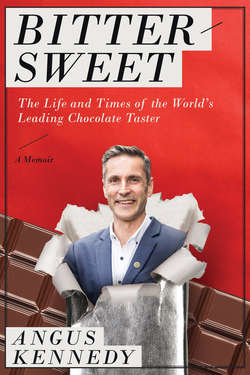

Journalists and television presenters with jobs that I would die for say to me, “Angus, I want your job.” We go into the TV studio (where I hand out chocolates, of course) and it goes like this: “Now, let’s go over to meet our next guest, Angus Kennedy. Yes, we have the world’s expert on chocolate here in the studio, who is, wait for it . . . paid to eat chocolates. I want his job.”

And I’m thinking, as I am being interviewed and almost revered (even more ridiculous), “Well, yes, I do eat chocolate for a living, but I also do lots of other things as well. I run a small publishing business, I edit, I write articles, I sell books, I take kids to school, I empty the dishwasher, I try to fix broken lawn mowers, and I attempt to mend things that I can’t mend just because I am called ‘Dad.’” They don’t see the other bits, like me trying to maintain my weight with a bad knee and having to get all my teeth capped in advance at huge expense due to the large number of sweets I have to eat.

But they’re having none of it. They have a real Willy Wonka who is paid to eat chocolate, and that’s enough; nothing else matters. So, meet Angus Kennedy, the British eccentric who does absolutely nothing else at all but fly around the world gulping copious amounts of delish confections.

We have to dream—it’s good to dream. Life is made possible by dreams. Perhaps we want to believe that we can eat candy all the time and be paid for the pleasure. Dreams deserve to be where they belong, realized before we die.

Well, I thought, if so many people want this “dream job,” which I do in part have, then of course I will write a book about it and how I landed it, and show you what it’s like in a secret industry about which so little is known. Oh, and I will address the question “Will we run out of chocolate?”

I did seem to achieve the impossible, so I am going to tell you about how I became a Willy Wonka. I failed my way to success! Sometimes you don’t really have to work that hard to succeed. We make it easy to make life difficult, but make it difficult to make life easy.

In fact, the harder you chase your goals, the more likely it is that they will run deeper into the forest. And, most likely, what we are chasing is something that we never were supposed to catch anyway. We keep hunting, never catch anything, and die pursuing something that was never supposed to be for us. Luckily, I failed a lot.

And then I made it at fifty-two years old, going gray, relying on my five kids’ memories, and having to ask my wife to speak a little louder and read the menu for me at the local French restaurant in Kent when we go out, because (again) I forgot my reading glasses and it’s too dark.

—

If I can make it at fifty-plus and change my career against all odds, with everything I have been through, then come on—you can do it, too. We can achieve anything in five years. I am here for no other purpose than to inspire you to be the great person that lies within you, the person you were all along.

I do keep failing. But the only real failure is to not get up again. It’s not about how you are knocked down, it’s about getting up—time after time.

So here I am, for better or for worse, at your service. Was this absurd job my planning? Will I be a chocolate Wonka of tomorrow? Who cares? I don’t know, but I embrace whatever happens as long as something happens. Success is being you as you travel through the changes.

My story is about how I landed the best job in the world despite the worst preparation possible. We all seem to worry about what we don’t have as opposed to thinking about how great it is to have what we do.

There is a magical space beyond what we can dream. For some of us, great success happens, and for others it simply doesn’t. But those who succeed are able to travel beyond their dreams without fear. I’m still trying, but no one goes anywhere by doing nothing and fearing change. You have to get up again, and again, and again. And then discover what the actual real dream holds for you.

So let’s get on with the important stuff, namely my entry into the world of candy and how I became a chief chocolate taster, got the best job in the world, and became a TV personality by failing at everything and finally accepting and letting go. Here’s how I mysteriously seemed to get ahead with the worst preparation and entered the secret doors to the Kingdom of Chocolate. Here’s to always expecting the unexpected—the only thing we can ever truly expect.

Jump into the time machine and get comfy, it’s time for liftoff. I’m going to take you back to 1973, to my extremely unpredictable family house in Muswell Hill, North London (a story in itself), where the candy-crazed kid was in the making.