Читать книгу Bittersweet: A Memoir - Angus Kennedy - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1 Mad Dogs, Vodka, and Candy

ОглавлениеMuswell Hill, North London, 1973

I never saw much of our mail as a child, as most of it was ripped up by our overexcited dogs, deranged rescue cases from a 1970s Battersea dog shelter. As soon as the tip of a letter made itself visible through the letterbox, these hopelessly untrained hounds would come cascading down the stairs in search of their morning snack and collapse in a heap, waiting for the mail to drop conveniently into their mouths. It was a race between me and the dogs to get to the door. There was good reason I was keen on beating them to it.

My mother was probably sleeping over her desk in her home office on the ground floor, holding an empty vodka bottle concealed in a paper bag. (I didn’t need to look; I just knew.) With my father—who was, unbeknownst to me, in the very late stages of cancer—bedridden, she had given up completely.

Booze was her new master, and at nine years old, mine was fast becoming candy. It was my job to rescue the candy and checks in the mail, or the mortgage wouldn’t get paid. I was unaware that our mortgage was heavily in arrears and I didn’t know that not all households were like mine, but I had a feeling that things were not right.

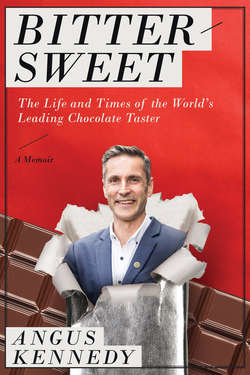

In essence, I should not be the world’s leading chocolate taster today; I should be on the scrap heap!

Despite the somewhat uncomfortable combination of candy, cancer, and empty spirit bottles badly hidden around the house, it wasn’t until later in life that I realized my childhood home was not normal by any standards at all. It was, however, a brilliant place for learning about life and the confectionery industry. At the time, I ate candy to keep living; nowadays I eat it for a living. I am still dependent on the stuff today.

The Kennedys’ unlikely candy school took place in our Edwardian family house in Muswell Hill, North London. The dogs—Peggy and Sheba—and I ate the sweets, my mum knocked back the vodka, and my dad struggled with the malignant tumor feeding off him.

Oh, and the banks didn’t want to be left out either, so they were swarming like wasps for their fix of what seemed to be an imminent repossession. It was a magnificent cocktail of catastrophe, high sugar intake, alcohol consumption, and my disastrous education.

Candy samples from confectioners around the world arrived regularly through the letterbox, and both the wretched animals and I couldn’t wait to see what goodies were in store. We were all hungry. The free samples were from companies that wanted my mother to write about them. I was keen to beat the dogs to the door, as the mail contained what was often my breakfast too.

My mother, when she eventually woke up from her naps on the desk, wrote about these new-to-market confections for the family confectionery magazine, which today is called Kennedy’s Confection. The journal, of which I am now editor, is one of the oldest business journals in the world; it even survived two world wars. Though the original name was Confectionery News in 1890, it has only changed names twice in 125 years. At this time, during the 1970s, it was called Confectionery Manufacture and Marketing, which was a mouthful for our customers, most of whom were learning English as a foreign language, so I changed it to its current title, Kennedy’s Confection, in 1990.

The family company was started by my father, John Kennedy, and my mother, who used the pen name Margaret Lang, who together acquired the magazine in 1971, along with many other magazine titles, including a turkey industry magazine, an ice-cream magazine, and something called Chemistry and Industry Buyer’s Guide, which I never even tried to understand because I always used to think it was the most boring magazine ever printed.

Today, many of the dog-eared issues are in my cellar, sitting in suitcases and cartons, or in a dark corner of my attic slowly being forgotten about over time. I am the only person now alive who knows where they are. Sometimes I take a step back in time and go up to the loft (which incidentally was built in 1860 so adds to the effect nicely), sit on an old oak beam, and tune into the past.

Sweets tended to be defined by their shapes one hundred years ago, and many products mentioned in the magazines in my attic are now all but forgotten, with product names like Marzipan Sweets, Acid Drops, Fairy Rock, Twisted Barley Sugars, Silver Comfits, and my favorite, Voice Pellets. Quite what they did for your voice, I still don’t know. Perhaps they provided the energy to shout louder for more drops.

Even the currency was better back then. Buying anything was far more engaging than it is today. The money had character and influence on your feelings; we could go into a sweetshop on the corner with a half farthing, a shilling, a crown, or guinea in our pocket. How romantic shopping for sweets used to be with words like that! Now it’s a mere mundane mechanical swipe of our debit card over a machine as both customer and seller fail to look at each other, register any appropriate human engagement, or smile.

Yes, shopping for sweets, though rewarding, is now just a monotonous beep in a supermarket as we watch them move along the conveyor belt, as we feel guilty and wonder if behind their wry smiles the checkout staff are really thinking we are just plain English Saddleback pigs. It’s nothing like walking along the beech-tree–lined country lane to the village shop with your last farthing and wondering with every step what dreams it could buy; perhaps I am far too romantic.

My mother was the editor then, and she also sold advertising space, which is a tough job, especially with a dying husband in the background. Over time my father’s illness took its hold, and with my mother’s drinking, only one magazine made it through to today—the confectionery magazine.

So, the sweets arrived in the mail and I would dig in right away and my mother would come into the lounge, before taking another secret swig of her bottle, and ask me what the sweets tasted like. I would say, “Yeah, great, Mum, sweet.” She would nod in approval, return to her desk, push her greasy glasses back to the top of her nose, and hit the keys of her self-correcting IBM Selectric golf ball typewriter. For the rest of the day, in between sleeping and sipping from a bottle wrapped in an old Budgens supermarket paper bag, she proceeded—God knows how—to write an issue of the confectionery magazine for that month.

The magazine had great authority. Oddly, my mother was a very good writer and wonderful with people. She managed to hide the drinking problem (with my help) in the beginning. Perhaps it was all that booze that gave her such a wild imagination.

Sometimes, though, I craved a conversation with a normal mum. I used to think a lot about life, and I would often sit alone on the grassy bank beside the school playground while my friends played football.

I never really found anyone to fill the gap until my mother finally married again, so for the time being I learned to reason for myself, which became a huge asset and in some ways taught me to be spiritual, as I would find myself talking to an imaginary guardian angel, something I still do to this day.

I would watch the other kids kick the ball from left to right and get upset at random moments when they didn’t have the ball and duly found myself looking for reason for my place in the world, if it wasn’t shouting about the placement of a ball. When I took a good look inside, I felt that I was just as freaky as my mother.

There was life in between my family’s nourishment of confectionery, booze, and nearer-to-death-every-day experiences. In a way, perhaps, both Mum and I were addicted and needed our regular fixes. I didn’t know any other way. There always was and always would be endless amounts of chocolate, toffees, bubble gum, and whatever I wanted, just about whenever I wanted to eat it. But free candy for a schoolkid was an eyebrow-raising thing to have on tap no matter what was happening at home.

In those days, you could eat as you wished and not be in the slightest bit concerned about what you ate. We didn’t worry about choosing fair trade, UTZ certified coffee beans, or Rainforest Alliance–approved chocolates, for example. We didn’t feel guilty if we chose our food from non-sustainable sources or from children trafficked into the trade in Western Africa. And we didn’t worry about the nutritional content. We didn’t know any better.

Our confectionery in the 1970s was packed full of artificial colors and flavors, but we didn’t mind. We quite happily got on with the important task of destroying the planet. Nowadays, we’re bombarded with new, often conflicting takes on why we should or should not eat something. But in those days, we did as we wanted and didn’t care too much that 80 percent of our confectionery contained artificial colors. (Now 85 percent doesn’t.)

For better or for worse, my childhood diet was brilliantly inappropriate. I certainly wasn’t on the receiving end of good nutritional advice. It didn’t seem to make a huge difference eating all that lot then. Despite my dreadful diet in my youth, I went on to row for England for the Under 23’s British junior team in 1986 in a coxless pair, and that was just before winning Henley Royal Regatta in a coxed four, a few years later.

Here I am today as one of the leading experts on candy and sugar consumption.

But now at least I can say I know how bad the things that I am eating are, when previously I had no idea.

My diet was a hit-or-miss affair. Breakfast, for example, was cooked in a frying pan that was seldom washed up, so fried eggs would have these disgusting lumps of burned garlic embedded into the base of the new, crispy, overcooked fried eggs that went into the pan.

I was overweight and my teeth were desperately out of line and full of gaping holes. I did have some dental treatment when my mother remembered, but it wasn’t until later in life that I sorted my teeth out and capped them all. I remember having a night brace at one time, to straighten my teeth out, but the dogs, to their delight, discovered it and chewed it up when I left it on my bedside table. It was never replaced.

The dogs’ teeth were in a bit of a state, too. Actually, after a while, they had no teeth left to attack the post or my brace with. Perhaps it’s because they loved the toffees so much—or rather my friends and I did. Part of the fun would be to test the toffees on the dogs and watch the poor creatures screw up their faces as their jaws stuck together. In the end, they just couldn’t be bothered to chew anything at all and swallowed most sweets whole, including bubble gum still in wrappers and a good proportion of the important letters and checks for the ailing family business.

The tiny family publishing business was based in our home. Letters were strewn all over the kitchen table, in drawers, and on the couches, with typewriters on tables and telephones dotted around the ground floor.

Peggy and Sheba, we used to joke, were the complaints department, and no kidding: I saw letters being screwed up and thrown to the dogs, who ripped them up, along with unwanted bills and terrible black and white photos of marketing directors with huge collars who wanted their faces published in the magazine. Everything was left in pieces across the floor. It was definitely the worst way to publish magazines and run a business, but there were no laws or rules, and everyone did as they pleased. It’s actually astonishing the company survived.

Peggy was called Peggy because one leg didn’t work very well from when she was a puppy, and she always had one ear up and one down and couldn’t hear too well, which explains why she never did anything that was asked of her. You used to say “sit,” and she would simply get up, limp away, and focus on doing the entirely opposite of whatever you asked her.

On vacations, she was part of the family with the cringeworthy kids and the embarrassing dogs that would chase sheep all over Welsh farms while you were trying to have a quiet picnic, enjoy the view, and go unnoticed. We lived in dread that a local farmer would leap over a stone wall with his shotgun and take our dogs out.

Sheba was Peggy’s mother, and her trick was to chew the lovely Edwardian sash windows in the house when you opened them. She had a thing about windows and car seat belts, which added to the general madness of our house. As soon as you opened a window, she would race into the room and leap toward the base of the sash, hang from it without her back legs even touching the ground, and bite it furiously. Absolutely nuts!

There wasn’t really any one moment when we became that crazy candy family in the leafy plane-tree suburbs of North London. We were just always a bit odd from the beginning. There was a reason, I guess, for the neglect of my well-being. But, no, don’t worry! This is not an I-was-an-ignored-child book. Far from it; some say I could claim title to the best childhood ever—free sweets all the time and a mother who hardly knew or cared if I went to school.

I didn’t think much about being different until later on. When I started senior school at eleven years old, I discovered that my friends had things like clean bedrooms, ironed clothes, and other curiosities. I was used to being able to write my name in the dust under my bed and surviving with one clean pair of socks a week. The socks would stand up stiff without bending by Friday.

However, the layers of dust had been like this for many years. Years before my father contracted cancer, I developed a nasty lung condition called pleurisy, when I was six years old, that nearly killed me before him.

My diet was terrible for as long as I can remember, since my mother had always been drinking. She boasted that she drank Guinness when she was pregnant with me, right from the start. So even at the age of six, there were times when the candy was all there was to eat—so it was unsurprising that I fell ill occasionally. But I knew this illness was bad when my relations started turning up at the front door with presents and all sorts of goodies, even store-bought candies. They were a rare thing; we Kennedys never had to buy sweets.

I was left in the living room, where I could hear friends and relations sniffling and blowing their noses outside the door. I must have looked a bit rough. They talked as if they might not see me again. Even the hospital staff nurses came out to me rather than having me go to them, so I knew something was up. But at least I finally received some attention, another relatively rare commodity in the house.

There was a lot of whispering behind the living room door during my home hospital experience. I didn’t know it, but I was on the way out. The dust had taken its toll on me. I was moved down to the living room for weeks on end. I think my mum realized that the bedroom full of dust was not such a good idea.

I had lost the use of my left lung. I was nearly gone. When you are seriously ill, you don’t actually know how close you are to the end, especially when you are young. It’s a bit of a novelty. You just think it’s cool that the headmistress comes around to say hello and brings a present from the class with a signed card from all your friends saying, “Come back soon, we miss you.”

People around me seemed to be doing a lot of crying, which was a bit puzzling. I must have been close to death, but at the time I felt beautifully dizzy—there was no pain, but it was difficult to breathe. A nurse visited every day from the hospital. Each morning, I would lay on my stomach while she massaged my back, pressing hard, and with every push these hideous dollops of brown rubbery phlegm would come firing out of my lungs and into a saucepan on the floor. I’m guessing it was probably not washed up afterward and used to boil the vegetables.

The discharge from my lungs was so hard that these hideous rubbery missiles almost bounced out of the saucepan, much to the dogs’ delight. They were never too far away to make further investigations into any new types of textured food.

I remember going “spacey” as I lay down on the couch one afternoon, staring as the ceiling rose. I found everything and everyone a little distant and dreamy. I could sleep for hours with no wish to get up. My body had become part of the stationary elements of the room. I remained on my couch, staring at the black-and-white TV and gazing at the cobwebs forming around the ceiling, for weeks on end.

I knew every inch and every crack of the room from my position, and as the days passed, I felt I was becoming part of the room and no longer a mobile, active part of everyday life.

As you can imagine, my health was probably suspect before I got the lung infection. My bedroom was so cold the ice was often on the inside of the window, and my bed was right next to the windows, but I think that was common in those days. We didn’t have central heating; it was all coal and gas. To this day, I can sleep anywhere, no matter how cold it is.

I was also quite overweight at six years old. It’s just as well, really, because I lost a lot of weight while sick. I remember lying down day after day, watching Hector’s House and The Magic Roundabout kids’ programs and refusing to eat anything for weeks; nothing, not even a single American jelly bean or a licorice-flavored Black Jack chew. There comes a point when you decide if you want life. They can try to rescue you with all the medications they like, but you have to be a part of the rescue.

It’s a beautiful feeling, drifting off to the other side—so much better than Earth. I am not frightened of death. I have been close to its embrace on at least two other occasions, and here, with a lung infection and antibiotics not working, I could see why there was a sea of cards and cuddly toys on the mantelpiece over the nasty gas fire that was put there in place of a beautiful Victorian-tiled open fireplace.

There is something about inhabiting a body that has no wish to move that enables its inhabitant to tune into it. The silence speaks—you can hear your blood pumping through your veins. A bit of peace is something that I only dream of nowadays with my five children.

But I never once believed I would die. Being unaware of being ill saved me, really; ignorance of what can polish you off can be a great form of medicine. I had a friend at college who seemed healthy and very happy. She went to see a doctor for a routine test, was told she had cancer, got really depressed, and soon after that passed away. I am sure the chemo and the anxiety killed her. I often think she might have lived with the cancer if she had not known she had it. Just like I lay there on death’s door but quite happy, without the thought of ever dying.

The decision to get up and live again seemed to be within me. I was drifting peacefully, waking up and not knowing where I was lying, and then the great day for my mum’s diary took place. One morning, my mother wobbled into the room, trying hard to look positive and to hide her despair while carrying the daily hopefully-this-time breakfast that she had lovingly prepared on a tray.

Each breakfast had new things to eat, laid out differently. Sometimes there were handwritten “get better” notes, or toys, or anything to help wake me up and take an interest. She was running out of ideas and I was running out of time, something of which she was acutely aware.

She must have blamed herself for ignoring the dust building up and the cold temperature of my bedroom. She would never have forgiven herself if I had left her.

But that morning, I asked for one of my favorites at the time. It was a toss-up between a Curly Wurly and a tube of Smarties.

“Mum, can I have some Smarties?”

The words took a moment or two for her to register, as my simple statement seemed to hit her like an alien magnetic force field.

She nearly dropped the whole tray of breakfast as she stood in front of me with her mouth open and a look of uncontrollable panic at the thought I might change my mind. She placed the tray on the coffee table while the dogs moved in and hugged my emaciated body so tightly my ribs nearly met from both sides. There was such a commotion. It was like she didn’t have a second to spare in case I really did change my mind, fall asleep, or succumb to some other dreadful inconvenience like dying.

She grabbed the tray and ran into the kitchen, bacon and all sorts of goodies flying off in her wake, to the complete delight of the frenzied pets, who followed the trail of descending goodies. She searched frantically for some Smarties in the kitchen drawers. I could hear her pull them so hard, I was sure they would come clean out of the cabinet.

Not finding any, my mother grabbed the keys to her brilliantly underpowered Renault 4, skipped out the door, revved the tiny 950-cc engine so much I thought the car would explode, and raced up to the corner shop on Highgate Hill. She returned with the sacred candies, tore the lid off the tube with pieces firing in all directions, handed it to me with her shaking hand, froze, and then waited in great anticipation for me to start eating them without taking her eyes off me.

Another unavoidable and almost crippling hug came my way, and then she was quickly on the phone to tell “Mother.” She always called her mum “Mother.”

“He’s eating, yes, Angus, he’s eating now,” she screamed into the phone. It was a truly great day to have one less name on Muswell Hill’s homemade death row list.

She really did love me; she did care a great deal about her kids. To this day I never blame anyone with a drinking problem. People with alcohol dependency do not love you any less, even though it seems that way. The love is always there, deep down behind all the booze and confusion.

It takes some wisdom to see through it all. Better surely to have a drug addict who loves you than a healthy parent who doesn’t. Ironically, I learned more from my mother than I would have if she had been in good health, and I can’t blame her for the way she was. You have to be very strong to deal with the forces that drive you to drink. Moreover, you can’t blame yourself for not being able to rescue anyone from it. They alone can make that final decision, just like I did, in a way, when I decided that the mini-Wonka would live on!

After my first close shave with my maker, I tried not to inhabit my body for illness anymore. It doesn’t really matter what the illness means—what matters is the meaning we give to the illness. If you survive, you learn; if you die, they learn. At last I was on the slow road to recovery. The chocolate treats that I had eaten to fatten me up before may well have saved my life. It’s difficult to finish off a candy kid.

—

My mum changed a little after realizing that my immersion in dust was not of great use to me or the rest of my family. I considered my brother, James, two years older than me, the lucky one, as shortly thereafter he went to boarding school. My half sister, Helen, from my mother’s first marriage, was eleven years older than me, and it wasn’t much longer before she was off to university and I was left in the house.

However, after a short respite, the dust and mess reaccumulated, causing another looming problem. This time it was in my bedroom, where another close shave was on its way, ready to take me away in the middle of the night. It wasn’t long after the pleurisy; I was still six years old.

If you have ever woken up to flames in your bedroom, you will never forget that noise or the terrifying sight reaching to the top of your walls.

After my lung condition was diagnosed, I had been given a breathing apparatus that basically consisted of a “placed candle” under some waxy substance to keep some liquid hot and airborne, I guess to help me breathe at night. I hated it. It was the size of a small saucer and could be placed anywhere near the patient. My parents were so frightened of me contracting a lung infection again that they were adamant about this new routine. By trying to save me, they were unwittingly planning another potential casualty.

So, every night a live flame was placed on my bedroom mantelpiece, next to a few cuddly toys and old Airfix model boxes, to burn until the following morning. Above it were posters stuck on with dried Blu Tack that always came down, and around it were all sorts of other very-willing-to-ignite articles and tubes of glue. I guess it was bound to happen at some point. I’m not an expert on house fires, but it seems like in the 1970s just about anything in your bedroom could catch alight rapidly.

If you have suffered a house fire at night in your youth, you may never sleep soundly, no matter how old you become. You wake to any noise. Since the night my room caught fire, I have always been a very light sleeper.

I am not sure how I woke up. There was so much smoke, I should have been unconscious. I found myself sitting up in bed watching the magnificent display of huge orange flames burning up the curtains at the side of each window. The flames were so hot and I only had the covers to keep the heat away. Everywhere I looked it seemed there were flames licking everything, and I was having trouble staying focused as my blanket and sheets started to catch fire at the edges.

In such a situation, you might want to scream as loudly as possible, but my voice was hoarse and weak from the smoke, and I felt confused and dizzy. It was a miracle I was sitting up in bed at all.

It wasn’t long before I couldn’t really see anyway; I was short of breath and unable to move. I wanted to scream but I couldn’t. There was so little oxygen that nothing seemed to work in my body. Doesn’t anyone know I am going to die (again)? I thought. I want my dad, my mum, anyone.

In a house fire, you’re likely to pass out and suffocate long before you fry, but I was awake as the flames worked their way up the wall, sizzling the woolen blankets in search of their grandest prize of all—a human life.

The noise was terrifying. Cracking, spitting, small things in the room popping, wooden curtain poles falling off the walls: you never forget the deathly noises of being so close to a fire.

Where’s my mum? Is there no one there? Where’s my dad? Are my parents dead too? Help me, please, God, help me.

I could think but not act. I was going to pass out, be the fuel and not the victim.

My mum always slept heavily, as she was likely unconscious from the bottles of anything she had left that day. My dad was a big man with a heart of gold. Though none of us knew it, he was soon to be struggling with cancer. Was I going to be the one welcoming him to heaven first?

There was a huge crash. A wall coming down, a ceiling, I don’t know. A blast of some sort? I heard screaming, my name being called out. My bedroom door flew off its hinges, and this time it was Dad’s turn to save Angus. My angel and my hero stood strong at the doorway, and what a magnificent display it was to see him there with the door lying on the floor at his feet.

He flew across my room to rescue me from that burning hell. I was in my dad’s arms, wrapped up in a cold blanket and whisked down the stairs to the sounds of sirens and the imminent arrival of the emergency services.

After being close to death a few times, I am not scared of it. I should be dead, so I just think I am lucky. Anyway, it’s not the length of the life that matters, it’s how much we can teach before we die.

It turned out it was only a fire in the bedroom and hadn’t spread at all, so what seemed like the whole house burning down to me, was just the curtains and a few posters. My father extinguished it easily, and it wasn’t long before things were back to normal. Though my school friends were never sure what to expect when I next came into class. This time, they really thought I was a spectacle returning to school after being starved, baked, and asphyxiated. There was never a normal entry to school for me at any time, something I just got used to. I guess nothing has changed, even today.

The lung infection and the house fire left a half-baked, nutritionally starved, candy-laden kid on the block; my general health was affected even a few years later. And as the time passed, I had to watch out for another hazard—the less conventional ways of cooking my mother employed.

Eating was another near-death experience. It was almost a race to see who would go first: my dad, mother, or me. We were all truly excellent candidates for what now seemed to be regular appointments with potential death.