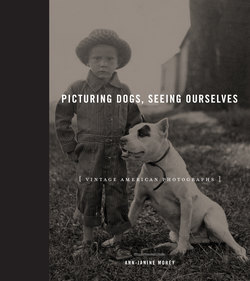

Читать книгу Picturing Dogs, Seeing Ourselves - Ann-Janine Morey - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

[Romancing the Dog]

I come from a family of picture takers and storytellers, and after a while it is difficult to tell the words from the pictures. The pictures begin with my Grandpa Morey, who wasn’t much for words but who had a mechanical and technological intelligence that was quick to recognize the potential of the camera. Like many people of their time, my grandparents were minimally educated but schooled for a lifetime of hard work, stemming from their rural upbringing. Both of my grandparents Morey were employed by the Agricultural and Industrial School in Industry, New York (near Rochester), a facility run by the New York State Department of Corrections that housed juvenile delinquents who served time in this benign “cottage system” for six months to a year. Alice Elizabeth (White) Morey was the housemother who cooked and cleaned for a dormitory of miscreants. Ibra Franklin Morey, a shop teacher at the facility, lived virtually in the shadow of Eastman Kodak, and had even worked as a machinist at Kodak before moving to Industry. Grandpa Ibra passed on his visual intelligence to his only son, my father, who has taken and developed pictures all his life. Dad works only in black and white, on the grounds that it is the true revelatory mode for photography.

Both of my parents are storytellers, however, so both have conspired to create memorable images whose genesis is neither picture nor text, but both. My mother is the daughter of a Free Methodist minister who traveled the coast from Florida to Georgia during the Depression, hauling his family from one poverty-stricken post to another. There are virtually no photographs of her childhood, which might explain the wealth of words at her disposal. Her stories are El Greco grotesques, embellished by her gimlet eye for detail, records of a South and a religious framework that have largely disappeared. A scientist by training, she has an acute sense of observation that extends from the human to the animal world, and because she loves animals, she naturally constructed memorable stories about the family pets along the way to preserving the larger moments of family history.

My dad has a gift for verbal snapshots, and he has created memorable images of my Canadian great-grandmother and the hardscrabble farm that was a summer home for him. In an unpublished memoir, he describes the scene in figure 3 as indicative of his grandmother’s ingenuity in finding things for him to do:

One of those jobs was that of “breaking” calves to a halter. At milking time I fed the calves, holding a bucket of separated milk under their noses while they drank, at which time they would frequently buck the pail and slop quantities of milk over me. Grandmother’s solution was to have me teach the calf to lead and to that end she had me tie a rope around the calf’s neck and the other end around the neck of our faithful dog Sailor. Of course this made for a totally unmanageable situation and I found I was neither strong nor heavy enough to counter the wildly bucking calf and the bewildered dog. Nevertheless I was quite serious about training the calf to walk on the end of a rope, for what good purpose it never occurred to me to ask.

Dad’s stories preserve a sense of a childhood at once rare (not many middle-class boys grow up with juvenile delinquents for playmates) and filled with longing for a childhood no longer possible, if it ever existed at all. Except that it does, now, because the pictures and the stories have made it so, and it took both words and images to make this happen.

As a child, I pored over the family photograph albums created by my young parents, who, like most parents, documented less and less as time went on. The pictures that fascinated me most were the ones of my beautiful young parents and their dogs. Probably the largest photo in our family album is of Lord Jim, a black and red dachshund out of CH Favorite von Marienlust from the Heying-Teckel kennels. He was purchased on Valentine’s Day 1947 and renamed Cupid, or Cupie. My parents were proud of his lineage, for Cupie’s sire was a world champion. Several years later, Cupie was joined by a peasant companion, a dowdy red female dachshund named Mitzi, whose biography included the romance of rescue from abuse. Although our extended family has owned several dachshunds, clever, good-looking Cupie (fig. 4) was the ur-dog, setting a narrative and visual standard for canine achievement that no other dog could approximate. Cupie did have a short-lived predecessor, however, who adds a significant visual to the family romance with dogs.

FIGURE 3

Don Morey and Sailor. Snapshot, 1929, 10 × 6.1 cm. Photograph by Ibra F. Morey. Harlowe, Ontario.

In figure 5, my parents are standing at the backdoor of Huron, one of the cottages on the grounds of Industry. It is September 1946, they are posing for my Grandpa Ibra, and they have been married just a few days. My mother is slim and proud in her elegant dressing gown and slippers, my dad resplendent in a satin-trimmed bathrobe and unscuffed slippers. The foliage behind them—cannas and morning glories—suggests a garden, and the embrace of mature trees as part of the frame indicates an unseen lawn. In the palm of my mother’s hand, sitting upright and begging for a treat, is their miniature dachshund, Buddy von Hixel. My mother and father are smiling at each other and the dog, and their hands are joined through the dog.

FIGURE 4

Cupie. Snapshot, 1950s, 14.4 × 17.2 cm. Photograph by Donald F. Morey. Los Angeles, California.

I never saw them this way; no child ever does. We catch up with our parents in the grueling middle, and sometimes the lost brightness is irrevocable. In that sense, this picture is like a glimpse of a lovely garden that has since been forfeited. To add to the poignancy of the moment, Buddy died months later of distemper. My parents were so distressed by his death that they replaced him literally and symbolically with the next canine Cupid, the Valentine’s Day Lord Jim. From the beginning and through all the vicissitudes of a long marriage, dogs remained a faithful, comforting constant. This photograph summarizes one of the themes that attend the presence of dogs in our lives, an Edward Hicks vision of a peaceable kingdom of mutual and loving communication across species, across time.

In the 1893 canine autobiography Beautiful Joe, the eponymous dog narrator tells a story about Eden he has heard from his human companions: “Well, when Adam was turned out of paradise, all the animals shunned him, and he sat weeping bitterly with his head between his hands, when he felt the soft tongue of some creature gently touching him. He took his hands from his face, and there was a dog that had separated himself from all the other animals, and was trying to comfort him. He became the chosen friend and companion of Adam, and afterward of all men.”1 More contemporaneously, there is a quotation on nearly every website devoted to dog love that says, “Dogs are our link to Paradise. They don’t know evil or jealousy or discontent. To sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring—it was peace.”2 These sentiments underscore the uniqueness of the canine-human relationship, and hint at why photographs of humans and their dogs could be about more than simply recording our attachment to our pets. There is something ineffable about the quality of communication between ourselves and dogs that draws us back.

FIGURE 5

Honeymoon Buddy. Snapshot, 1946, 5.9 × 10.7 cm. Photograph by Ibra F. Morey. Rochester, New York.

ANIMAL STUDIES

“It is a lovely thing, the animal / The animal instinct in me.” These lyrics from a 1999 CD by The Cranberries appeared at a cultural moment when scholars and artists alike were engaging in a growing conversation about how “human” is related to “animal.” This academic and applied social movement—animal studies—continues to gather strength a decade later, and shares with these lyrics the affirmation of “animal,” “instinct,” and “animal instinct” as not only a force demanding new reckoning but a “lovely thing,” through which we may find our way to a healthier understanding of “human.”

Speaking of humans and all animals, John Berger argues in About Looking that the gaze exchanged from the animal to human world and back again crystallizes the profound atavistic connections between humans and animals, a connection that surfaces in both metaphor and visual art. W. J. T. Mitchell underlines this idea, noting that “as figures in scenes of visual exchange, animals have a special, almost magical relation to humanity.”3 As we’ll see, this kind of mystical language about the animal-human relationship closes the circle no matter what the starting point, whether the discussant is an academician, novelist, memoirist, or musician. The enigmatic relationship between animals and humans is part of a long-standing philosophical tradition dating back to Plato and Aristotle and proceeding through the usual greats of Western philosophy—Descartes, Kant, and Foucault, for example—as a range of commentators have documented.4 In an article prosecuting the dishonesty of metaphysics, B. A. G. Fuller discusses “the messes animals make in metaphysics.” In most philosophy, it is impossible to find a place for other kinds of conscious beings, and yet we routinely award dogs a kind of consciousness that automatically confers on them moral agency and purpose. And if they have some kind of moral purpose as conscious and communicative beings, then how will we address their lives, not to mention their suffering, in a philosophical universe composed of rational agency, free will, and divine decrees? The only way to keep the “system in order and man master of it is to shoo [the animals] out of the house altogether and stop one’s ears against their scratching at the door.”5

Writing in 1949, Fuller long preceded the animal studies movement that has so complicated and enriched our contemplation of animals in the past decade or so. His questions remain unanswered, although animal studies proponents are making a concerted effort to open that door, permanently. So challenging is this territory that Cary Wolfe compares giving an overview of the field to herding cats. “My recourse to that analogy is meant to suggest that ‘the animal’ when you think about it, is everywhere (including in the metaphors, similes, proverbs, and narratives we have relied on for centuries—millennia, even).” Additionally, once the animal is foregrounded, we are confronted with a “daunting interdisciplinarity” that makes the relationship between literary studies and history look like an orderly affair by comparison.6

Animal studies is moving beyond representative collections of animal images that document the presence of animals in art and photographs, although those treatments are a valuable platform. Art historians regularly have taken note of dogs in Western painting. While these presentations offer some commentary about the shifting functions of dogs in human life or the potential symbolic meanings of the dog, their primary purpose is to trace the presence of the animal over the centuries, thereby illustrating the close, but largely unexamined, relationship between humans and animals.7 Most of these treatments tell us more about the artist or the artist’s subjects than about the animal. However, multiple sources that document the presence of animals, and especially dogs, in cultural representations finally have compelled scholars and historians to train their gaze upon how all animals become troubling mirrors to humanity. With that awareness intrudes a counterreflection, an intense consideration of the ethical dimensions of this relationship. The animal nature of humanity intersects the human nature of animals as we jockey for some purchase on ideas about consciousness, ethical behavior, and spiritual selfhood, which may not be the exclusive province of the superior human. Indeed, in anthropomorphizing animals, we humans have created visual and textual images that at once trivialize our own lives but also the lives of animals, taking for granted that their lives may be manipulated for symbolic purposes that seemingly have no consequence for them or for us. But is this true? May we do this with impunity?

One response through animal studies is to reexamine our representations of animals, looking for what the animal might mean to us but with a concern for what our representation might mean for the animal. This approach tries to take seriously the proposition that our representations have meaning and import in ways beyond the “merely” visual or the “merely” literary. Susan McHugh asks that we take literary animals seriously, arguing that, “now that scientists are identifying the interdependence of life forms even below the cellular level, the pervasive companionship of human subjects with members of other species appears ever more elemental to narrative subjectivity.”8 Steve Baker, in Picturing the Beast, says that the representation of animals in popular visuals is an important pathway to understanding how we see them, and how we use them in our own cultural constructions. Erica Fudge calls for an animal studies that will promote an “interspecies competence,” by which she means “a new way of thinking about and living with animals,” such that the meaning of “human” and “nonhuman” must shift radically.9 Finally, scholars are asking about the difference between “animal” and “animality,” in reviewing cultural representations of animals and humans.10 Whether they are referencing painting, literature, film, or photography, what all these scholars have in common is their shared urgency about how much our intellectualized perspectives on “animal,” and thus on “humanity,” must change. “Animal” is, in Wolfe’s words, “in the heart of this thing we call human,” whether we approach it from a humanistic point of view or a postmodern point of view.11 We must engage in animal studies, for it is a crucial pathway for rediscovering ourselves as human animals who live in what Donna Haraway, in The Companion Species Manifesto, calls “natureculture.” Moreover, many of these discussions share a common trope, that of the liminal territory between the animal and the human.

In reviewing the philosophical tradition about animals, Akira Lippit offers a dense semiotic discussion leading to the conclusion that animals are neither here nor there, but in this liminal state they trouble our conscious reflections by their indeterminate status. Just as we toggle between our contemplation of the brain and our musings on the meaning of the mind, animals become the emblem of that journey. We imbue them with, or they possess, more meanings than are apparent in the mere facts of physical existence. In Lippit’s words, “animals are exemplary vehicles with which to mediate between the corporeality of the brain and the ideality of the mind.”12 We may perceive and understand more about animals than we are able to put into words, another conundrum for human beings who are so thoroughly determined in Western philosophy, if not overdetermined, by our ability to live by words. Animals may also perceive and understand more about us than they are able to put into words, although for different reasons. Again, humans meet other species in this liminal space where words largely dissolve but communication persists, perhaps because animals are more important for constituting human reality than we have realized or acknowledged. Lippit concludes that the presence of the animal is always poised to “disrupt humanity’s notions of consciousness, being and world. . . . Contact with animals turns human beings into others, effecting a metamorphosis. Animality is, in this sense, a kind of seduction, a magnetic force or gaze that brings humanity to the threshold of its subjectivity.”13

Thus we return to the mystical language of a visual force created and sustained by our relationship with animals. Temple Grandin has famously and successfully argued that persons on the autism spectrum have many things in common with animals. In particular, they share a common sensory field. Her groundbreaking work doesn’t denigrate “regular” people, but it does gently suggest that autism might be our doorway to a better way of understanding animals, and to understanding ourselves as animals with more capacity than we have realized. And Grandin wouldn’t mind if we reversed that statement and said that a better understanding of how animals perceive and respond to their world might open latent parts of our brains that we have closed off, including our understanding of autism as part of a spectrum of human creativity. “The animal brain is the default position for people,” she suggests, and in her hands the animal instinct is indeed a lovely thing.14

THE ROMANCE PLOT

This language of mutuality, visual force, and the liminal space occupied by animals and humans well suits my exploration of photographs of dogs and their owners, for there are few animals that carry as much history and cultural freight as canines do. The unattributed legend of Adam cited above is but one of many narratives that fill in what is missing from the biblical account and build upon a treasury of dog stories, legends, and myths. According to the Kato Indians of California, the creator was going around the world creating, and he took along a dog. “Nowhere in the story is any mention made of the creator creating the dog—evidently because he had a dog.”15 Not only is the dog a first companion in the creator’s opening activities; dogs are also the companions to the last human breath, guides to the underworld, and guardians of afterlife crossings both in myth and in practice. Cerberus, the three-headed dog, guards the gates of Hades, and in British folklore a large black dog with glowing eyes is a portent of death. In Louise Erdrich’s The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse, the reservation priest is alarmed by a visit from the devil in the form of a malevolent black dog that enters through a window, puts its foot in his soup, and bargains with him for the life of a child.

Russell Hoban makes extensive use of this lore in Riddley Walker, his remarkable novel about post-nuclear-war England and its fragmented language. Riddley, the postapocalyptic Huck Finn of the title, goes on a quest to understand the story fragments that record the devastation. Early in the novel, he tells the story of “why the dog wont show its eyes,” explaining that when humans enticed the first dog to a fire, they saw that the dog had the “1st knowing,” and it shared that knowledge with them. But they misused this insight, and finally their cleverness and scheming brought humankind to the Power Ring and nuclear destruction. From then on, “day beartht crookit out of crookit nite and sickness in them boath,” leaving humans and dogs hunting each other in a desperate search for food.16 Riddley says he’s heard that dogs could be friendly, but he’s never seen it. But later in the narrative, as Riddley’s pursuit of the story of the destruction of the world begins to reknit the narrative, Riddley makes friends with a lonely black dog, signaling one more small measure of healing in the blasted landscape.

FIGURE 6

Roswell. Cabinet card, 1890s, 10 × 14 cm. Photograph by Bolander. Monticello, Wisconsin.

While we would not expect to see such portentous implications in family photographs with dogs, the Eden-to-Hades versatility of the dog in its mythological form does help explain some of its manifestations in ordinary daylight. For example, when bereaved families created mourning pictures of loved ones, and especially of children, it was not uncommon to include an image of a dog as part of the funerary decoration. Figure 6 is a memorial card. These mementoes usually feature a picture of the deceased from life, but the image is decorated with flowers, wreaths, and other funerary emblems. In American culture, the dog represents home, and in this context it reminds the viewer that the home is now bereft of the beloved child, although the presence of the dog could also be a throwback to atavistic mythological meanings associated with canines. The association of the dog with death takes on a different aspect when we look at archeological information. In North America we have evidence of dog burials extending as far back as 9500 B.C.E., and in more recent North American sites (from 6600 to 4500 B.C.E.), humans and dogs were buried together. As the anthropologist Darcy Morey notes, “considering the attention commonly lavished on dogs in mortuary contexts . . . it seems clear that they are about as close to being considered a person as a non-human animal can be.”17 Although many animals have served as metaphysical companions for humans, dogs seem to occupy a special category.

As an avid young reader of dog books, I imbibed many of these dog motifs. I moved quickly from picture books to adult-style narratives in which dogs or horses were no longer talking animals but main characters along with the humans. I remember my mother ordering two books for me, Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty and Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. I never did read Verne, but I still own that copy of Black Beauty. But alongside Walter Farley’s black stallion series and Elyne Mitchell’s brumby stories, I read Jack London’s wild dog adventures, Albert Payson Terhune’s collie stories, and Jim Kjelgaard’s Irish setter books. I also loved Fred Gipson’s less well-known Hound-Dog Man, preferring it to Old Yeller, which most children find horrifying because the dog dies. Inspired by these books as an adolescent, I yearned for a purebred collie and fed every stray that came by our back door, much to my mother’s consternation. We adopted some of them, of course, so there was never a time I was without a dog, or a dog book, for that matter. Collecting antique photographs of dogs unlocked the cascade of words about dogs that I’d absorbed during my own childhood reading.

Rereading these stories was fun and troubling at the same time. I hadn’t realized how much these beloved stories were romances about human-canine communication. Interestingly, we seem to be enjoying a renaissance of dog romance, most of it retailed in nonfiction accounts of personable, remarkable dogs and their human relationships. I do not reckon with these narratives in this book, however. As heartwarming as many of these stories are, they are largely one-dimensional accounts of the canine-human relationship. As such, they occupy the same cultural role as any conventional romance fiction, where the central relationship is at first tenuous or difficult, misunderstandings must be overcome, the owner finally learns to “read” the love object (who has been reading the owner all along), and they live happily ever after. My photographs certainly document the longevity of American dog love, but many publications before this one have already accomplished that task, as I’ve discussed in the preface. Picturing Dogs, Seeing Ourselves provokes a different kind of conversation, one about the covert cultural meanings ascribed to the dog or marked by the dog’s presence in the photograph. The current spate of dog-valorization stories are not intended to stimulate cultural introspection; they are intended to make us feel better. While feeling better is a legitimate outcome of reading, it isn’t the only outcome I am pursuing here.

Furthermore, there is an unsettling underbelly to the romance plot. Romantic love can prove to be blind if not lethal. The romance plot is a formulaic structure that asserts the necessary domination of male over female, and encourages women to see their fate in these power-based terms. Through romance, women learn that they cannot trust their instincts in assessing the safety of relationship with any given male, and that they must be protected and rescued by that same male, whom they cannot understand but will come to adore.18 The romance plot may also encourage women to accept an implicit, and sometimes explicit, brutality in the relationship. Perhaps the heroine is foolish and hardheaded, and needs to be “taken” by force before she can see the rightness of the male’s conquest. A bad woman—someone who has used her sexual powers illicitly—is usually killed or otherwise punished in the romance plot. Our contradictory attitudes toward women are much like cultural ambivalence about dogs. James Serpell comments on the enigma of contradictory cultural attitudes toward dogs, observing that “ambivalence about dogs seems to be almost universal.”19 It seems that humans love and loathe dogs in equal proportions. We love them when they act least like dogs and most like adoring sycophants. Speaking generally, this mirrors cultural attitudes about women, who are praised most highly for being affectionate, beautiful, obedient, and servile.

The connection I’m making here, using the cultural and literary structure of “romance” to find women and dogs inhabiting the same script, is unsettling, but it is important to acknowledge the connection between women and animals, especially dogs.20 In the romance plot, dogs are to humans as women are to men. This also means that our romance with dogs has its dark side. Our domination and domestication of dogs has not always produced benevolent outcomes for dogs, any more than the romance plot has always produced benevolent outcomes for women. The literary device of the romance plot serves as an apt narrative model for how we construct our relational world with other sentient creatures. From animal experimentation to genetic engineering and dog fighting, men have ruthlessly exploited the canine capacity for assimilation. That is the shadow side. My photographs do not engage us in direct conversation about our cruelty to dogs, but they do reveal how we have used and manipulated animals for what are often ethically craven purposes. Although I want to honor the genuine beauty of the caninehuman relationship, I also persist in exposing the cultural moments when our dog love means much less than the appearance of love and respect.

I also use the word “romance,” however, in relation to my own beloved childhood stories. While some of these stories revisit the masculine fascination with naturalism and primitivism (itself a form of romance), others offer an enticing invitation to visit a benign paradisal world where dogs and humans communicate intuitively, where dogs are always noble and self-sacrificing and humans are willing to be tutored by the exemplary canine. These fictions are part of the cultural fabric that informs this collection, and they indeed have shaped our cultural values and sensibilities, even if we are only now discovering the dimensions of these fictional influences. Jennifer Mason argues convincingly that the dominant thread of American cultural criticism has favored the theme of wilderness as a critical formative factor in American culture and society. This focus, long the generative fence between male/female and nature/culture, is an artificial barrier to a richer understanding of the meaning of America. What is missing from the “manly male fleeing into the wilderness” trope? It is the presence of domesticated animals among us—and the meanings they carry. In Mason’s words, “domesticated animals have remained a critical blind spot in American studies, even in the work of those most committed to rejecting the dichotomized view of nature and culture, in which humans exist ‘outside’ of nature and contact between human and nonhuman renders the nonhuman ‘unnatural.’”21 Mason takes careful measure of some signal fictions and fiction writers in making her case, and work like this is an important ally in my consideration of photographs as another piece of evidence about the cultural importance of animals, dogs in particular.

In her study of modernist to contemporary fiction, Susan McHugh says that “as fictions record the formation of new and uniquely mixed human-animal relationships in this period, they also reconfigure social potentials for novels and eventually visual narrative forms.”22 Here, McHugh claims the entire expanse of cultural production as the legitimate territory of animal studies, flagging the fact that fictions about animals get translated into film, television, and digital media. Words do not supersede pictures; they become pictures. Although film, television, and digital media are beyond the scope of my book, the implicit heritage from photography and stories to moving pictures is clear, and so I call on a range of literature from the early twentieth century to the current twenty-first century. I have additional motives for including some reference to contemporary fiction, and they have to do with the substance of that fiction. I include fictional works about dogs and purportedly by dogs because so many of them offer a complex affirmation of the persistence of our Edenic longings, which have generated so much of our great dog literature. In The Dogs of Babel, by Carolyn Parkhurst, grieving husband Paul Ransome decides that he will teach his dog, Lorelei, to talk. His wife, Lexy, has died by falling, or jumping, from the apple tree in the backyard. Paul decides that the dog must have seen the tragic event, and he becomes convinced that if only Lorelei could speak, she could help him understand Lexy’s Edenic plunge earthward. At once a mystery and a meditation on what can be communicated wordlessly, The Dogs of Babel can take for granted that readers will accept the idea that an otherwise rational man might expect the dog to help him in his grieving because, in fact, we imbue our dogs with just such mysterious capacity. Invoking the mythological resonances of the dog’s name, Paul explains his project this way: “I sing of an ordinary man who wanted to know things no human being could tell him.” Picturing Dogs, Seeing Ourselves originates from the same conviction—that the dog can tell us something. In Paul Ransome’s words, “dogs are witnesses. They are allowed access to our most private moments. They are there when we think we are alone. Think of what they could tell us. They sit on the laps of presidents. They see acts of love and violence, quarrels and feuds, and the secret play of children. If they could tell us everything they have seen, all of the gaps of our lives would stitch themselves together.”23

VISUAL STUDIES

I couple my collection of antique photographs of people and their dogs with literature, where appropriate, in order to better understand some of the gaps in our public testimonies. But the photographs are always the starting point and the narrative stepping-stones. The field of visual studies articulates the understanding that images are not merely illustrations of cultural moments best represented by words but are themselves of cultural moment. In Visual Genders, Visual Histories, Patricia Hayes discusses visual studies as a new field. Quoting Christopher Pinney, she makes a case for acknowledging and studying the power of the visual to shape cultural history. Suppose that we “envisage history as in part determined by struggles occurring at the level of the visual.” And what if pictures are “able to narrate to us a different story, one told, in part, on their own terms”? What she is talking about, Hayes specifies, “is not so much a history of the visual, but a history made by visuals.”24

In the same spirit, I have tried to let the pictures suggest the story, rather than simply using them as illustrations for a story already determined by other sources. Moreover, while I want to give literature its due, I think that the communicative skills of dogs themselves prompt our interest in a more skillful visual comprehension. Alexandra Horowitz comments that she treasures dogs because they don’t use language. “There is no awkwardness in a shared silent moment with a dog: a gaze from the dog on the other side of the room; lying sleepily alongside each other. It is when language stops that we connect most fully.”25 That most animals don’t have language in the way in which we understand the term does not mean that they can’t and don’t communicate. It just means that we haven’t figured it out. But one effect of animal studies, on the applied side of things, is the awareness that better communication with animals is possible, whether we are talking about the most social of critters—dogs—or the mysteries of horses, cows, or pigs. We are learning more about visual cues in language and the subtleties of those cues. Temple Grandin says that animals see in pictures, much as autistic people do. So taking pictures seriously as evidence, inspiration, and narrative art could be a good step toward understanding what a more visually, as opposed to linguistically, oriented intelligence can discover.

I discuss my “visuals-first” approach to Picturing Dogs in chapter 1, where I introduce the physical formats that characterize the photo collection and offer some examples of how the images might be construed. More important, this chapter also broaches the question of a “visual rhetoric” created by juxtaposing seemingly unrelated images and weaving them back into their cultural context. “Rhetoric” is the ancient art of persuasion, a form of communication intended to sway an audience through eloquence, reason, or emotion. By “visual rhetoric” I simply mean the persuasive power of the visual and, in the case of the materials here, the communicative power of groups of thematically related images.

John Berger points out that, by itself, a photograph cannot lie, but “by the same token, it cannot tell the truth; or rather, the truth it does tell, the truth it can by itself defend, is a limited one.”26 That is, without the story that could accompany an image, all photographs are ambiguous, “except those whose personal relation to the event is such that their own lives supply the missing continuity.” Photographs without narrative, that is, photographs that have been disconnected from their context, are permanently ambiguous unless we construct a narrative pathway. The discontinuity of the images I have gathered here, for example, “by preserving an instantaneous set of appearances, allows us to read across them and find a synchronic coherence. A coherence which, instead of narrating, instigates ideas.”27 It is those prompted ideas that constitute the “half-language” of the visual rhetoric of photographs. Julia Hirsch says something similar in commenting that “family photography does not preserve the shadows of our experience but rather their external share in ancient patterns,”28 and these patterns take their shape and structure from cultural context. I extend Berger here by suggesting that we cannot only instigate ideas but create meaningful narratives from the half language of visual rhetoric. I do so using the photographs as primary artifacts, and contextualizing them with stories.

In her guest column for the PMLA, Marianne DeKoven comments that literature is replete with meaning-laden animals, and that “analyzing the uses of animal representation” can illuminate the ways in which we use animals and animality to perpetuate human subjugation or to obscure pernicious but subliminal value systems.29 Borrowing from DeKoven, my photographs are replete with meaningladen dogs, and analyzing the photographs can illuminate the ways in which we use dogs to perpetuate malign and benign value systems. As I demonstrate throughout Picturing Dogs, these images offer further evidence and narrative for understanding race, class, family, and gender in American culture. In these photographs, the animal body—in this case, the dog—communicates the presence of multiple “pernicious,” “subliminal,” and, I would add, sentimental and fervently affirmed value systems in American culture. The dog in the picture is part of a larger system of visual rhetoric.

The American preoccupation with respectability and achievement leans toward an index that involves the display of material goods. The dog came into play when “breeding” emerged as one of those watchwords designed to isolate the uncouth. Americans did not invent the snobbery of breeding, but we were quick to assimilate its implications. Speaking of the English, Harriet Ritvo shows how pet keeping became respectable among ordinary citizens, who came to think of the pet as a reflection of oneself, such that “most observers felt that ownership of mongrels revealed latent commonness.”30 It is no accident that the fascination with pure dog breeds coincided with the rise of nativism in American life, as political and cultural pundits used animal metaphors to analyze and judge human society. Chapter 2 considers the contribution of literature and photography to the American concern with material appearances, and the role of the dog in facilitating this kind of representation.

American racism and resistance to racism are represented in ways both saddening and surprising. Images of African Americans with dogs can be found throughout Picturing Dogs, but the ambiguous meanings of “animal” and “dog” take on ominous proportions when dogs and African Americans are in the same frame. The material in chapter 3 bypasses the spectacular racism of “black Americana images” and looks at ordinary photographs and snapshots of black and white people with dogs, wherein the gaze of the viewer may readily and inadvertently reinforce the insult offered to black subjects through the original composition.

The mystery, and sometimes playfulness, of family life surfaces in chapter 4. These photographs represent and misrepresent the reality of American family life. The display of home, children, and dog all go to the heart of the American dream. At the same time, these images surface the unarticulated dimensions of power and gender and race that are explored in other chapters. Defining “family” has become a way of excluding unwanted intruders. And yet the facility of the dog’s representational value undercuts the severe family boundary drawn by cultural purists. Several animal studies theorists have commented pointedly that the canine body stands in for the marginalized other. Teresa Mangum argues in “Dog Years, Human Fears” that the aged dog speaks for the aged person in literature, a sentimental strategy that upholds the value of marginal creatures. Marianne DeKoven and Cary Wolfe argue the same thing in relation to women. Following Carol Adams’s thought in The Sexual Politics of Meat, Wolfe endorses the idea that the sexualized bodies of women and the edible bodies of animals are both housed within the same “logic of domination, all compressed in what Derrida’s recent work calls ‘carnophallogocentrism.’”31 In fact, because most marginalized persons are at one time or another represented as animal rather than human, the dog, with its cultural fluidity, is most likely to stand in for any number of marginalized persons, not just women.

Chapters 5 and 6 follow up on the gender discussion initiated in chapter 4 by examining the collusion of literature with long-standing gender prejudices. Hunting photographs indicate the women who are missing from the cultural narrative, while also documenting male anxiety about masculinity at the turn of the century. Moreover, while the appearance of the woman hunter issues a cultural challenge to constructs of American masculinity, the female hunter also challenges current feminist positions about gendered perspectives on animals. Finally, the anxiety of white manhood is inflected by male attitudes not only toward women but toward African American men as well. While women seem to be excluded in the masculinity narratives, African American men may find themselves either assisting the great white hunter or being displayed as the prey, as is well documented in lynching photographs. Ironically, this same group of photographs invokes a well-attested cultural fascination with wilderness and American Edens, the narrative headwaters where childhood, innocence, and new beginnings are perpetually renewed, even if those paradisal cultural locations are not accessible to every American.

Traces of gender, race, and class dynamics knit all of these images into a cultural whole. In the conclusion, I revisit the perspectives of animal studies and visual studies in order to reflect upon what we can learn from a photographic collection like this one. An animal studies approach takes animals seriously as significant presences in our lives. We can learn more about ourselves as human animals by understanding more about what animals experience, on the one hand, and by understanding what animals contribute to our own understandings as persons, as a culture, on the other hand. In Animals Make Us Human, Temple Grandin looks patiently at each animal species—its unique abilities and requirements—by way of suggesting what each species can offer us and how we can better communicate with them. While the word “human” is the foundation for the word “humane,” we humans fall far short of that implied value in our behavior toward animals. Being more humane in our treatment of animals could lead to our becoming better humans. Thus it seems appropriate to acknowledge the Edenic longings that we attach to the canine body, and while I have undermined its efficacy in places, I also want to validate the honesty of that yearning. I don’t want to lose sight of the beauty that is expressed through a collection like this, so I allow a closing set of photographs to tell that story, and perhaps it is the story of our yearning for a more perfect and peaceful world.

THE CONTRIBUTION OF DOGS

Early in this project, one of my writing group members asked, “Why dogs?” I wanted to whip a smart answer back—“Because that’s what I collected.” But her question made me realize that, as much as I love horses, there is a reason why the antique dog pictures are so appealing. Of all domesticated animals, dogs have become our best friends forever. Cats are too independent to appeal to a broad spectrum of human personalities, and horses, which are more like magnificent aliens in our world, require a much different kind of communication from dogs. Horses can see nearly 360 degrees around them, but not immediately in front of them, because they need to be constantly surveying the landscape for predators. Despite the fond imaginings of horse owners, most horses would prefer to be with the herd, and their herd behavior makes them malleable to our interventions, which must be composed more of physical cues than voice and facial messaging. The cues we give to horses have to be unlearned from what we know about dog behavior, because what dogs respond to seems so natural. I talk too much to my horse, but I never talk too much to my dog, who responds alertly to tone, face, and physical cues all at once. We’ve learned that when a horse licks its lips and chews, it is mulling over what you have just tried to teach it, but the horse still has to decide whether it wants to comply. A good deal of enlightened horse training these days is more about the way we ask for cooperation than about the brutal “breaking” that once passed for training. Like dogs, horses are greatly romanticized, but they are also much more like mythological creatures who haven’t quite realized how powerful they are, so they tolerate our impositions without fully joining our culture. We don’t “ask” for a dog’s cooperation. We assume that will happen once the dog understands what we want, and we assume that the dog wants to cooperate no matter what.

More than any other domestic animal, dogs are cultural travelers, crossing back and forth from the canine to the human world, bringing their exotic animal natures into our homes while learning our language and our manners. Indeed, we are so close to dogs that we easily recognize the truism that owners and their dogs come to resemble one another over time, in much the same way that longtime married couples begin to resemble each other physically. A diversity of writers insist that there is something special about dog love. Marjorie Garber, for example, calls attention to the anomaly of masculine attachment to dogs from males who otherwise would be culturally expected to keep those unseemly emotions under control. In the title of one of her chapters, she summarizes one reason why we humans are so devoted to our dogs. It is their ability to convince us that we are the recipients of “unconditional love,” a quality of loyalty and dedication uncomplicated by sexuality or ambiguity. Moreover, dog love (our love for them, theirs for us) occupies “an emotional place that is not determined by sex or gender,” or for that matter by race, nationality, or age.32 Dogs seem to look beyond our physical selves and our faulty selves and lovingly accept the best parts of us.

In addition to their emotional and spiritual contribution to our lives, dogs have provided necessary services to human beings. Dogs hunted, herded, and guarded precious livestock, goods, and families. They pulled carts, wagons, and sleds—from door to door or across forbidding frontier expanses. They were playmates and companions. Children who saw their parents harness a horse for travel played with their dog by harnessing their patient pet to a wagon or cart. Or perhaps the parents colluded in that play, as we see in figure 7. This is “King the Alsatian Husky” and Spaulding T. Eaid, who is five months and seventeen days old, and not yet ready to hold the reins. Spaulding is propped up in a sulky. There are many play pictures like this from the turn of the century, often with older children who are perfectly capable of driving the dog. But at one time folks might have expected to harness the dog as a means of conveyance, and sometimes for more serious purposes than backyard play. Figure 8 is an early image showing a young woman, possibly Chinese, in her driving rig, which could have been originally intended for a pony but seems well adapted for a dog. In a much later photograph, “Carlo” is the dog power behind John M. Tuttle’s wheelchair, which has been constructed so that he can steer as the dog pushes (figure 9). Today, dogs still play a vital role for disabled persons, as well as serving as guardians and protectors in a larger cultural sense—they are used in police, military, and forensic work because of their keen sense of smell and their ability to understand the task before them. Their persistence and empathy has touched and supported humans through many a cultural upheaval. The dogs brought to Ground Zero to find survivors and victims have been lionized in a variety of publications and anniversary commemorations of the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center.33 Studies of the World Trade Center’s dogs and their handlers after those traumatic events are producing medical and mental health insights, as we use the experience of dogs to better understand our own.34

FIGURE 7

Spaulding T. Eaid and King the Alsatian Husky. Used RPPC, 1907–1920, 12.1 × 8.9 cm.

FIGURE 8

CDV, 1860s, 9.2 × 5.6 cm. Photograph by Ladd. Laconia, New Hampshire.

FIGURE 9

John M. Tuttle and Carlo. RPPC, 1926–1939, 13.1 × 8.2 cm. Davenport, Washington.

Finally, dogs provide the not inconsiderable service of companionship and entertainment. In the United States, it is this feature of dogs that largely defines their presence in our lives today, and we are accustomed to a culture that dotes on dogs, sometimes to extremes. At the same time, we are aware that dogs (and often other animals) are exploited, witness reports about dog-fighting rings and puppy mills. Sadly, the history of humans and dogs is filled with as many stories of our cruelty and indifference as of our admiration and love. And yet, no matter how we treat them, dogs come back. They are part of the picture even when we didn’t plan for it (figure 10).

FIGURE 10

Snapshot, 1920s, 7.7 × 10.5 cm.

The dogs in Picturing Dogs are witnesses whose bodies and presence speak far beyond the literal. Could we achieve some of these insights using other kinds of photographs, some other animal? Yes and no. For me, the dog was an accidentally chosen sorting device, and perhaps I might have assembled a different group of antique photographs to much the same effect. Thus the question must be posed another way: what does the canine bring to a photo that is not available in its absence? First, it adds a relational element that complicates the way in which we view the subject. Like occupational implements in photographs, the dog is part of the human subject’s self-definition, and the staging of the photograph offers insight into the various meanings that can accrue around the canine body. A sitter stooping to greet a dog chooses a different presentation from the sitter who has selected a formal setting, where the human and canine never touch. Moreover, although both may be isolated from the human, a canine posed at the feet occupies a different meaning space from the canine perched on a table. As I argue throughout this book, the canine body is symbolic of cultural values that still define our family life today. These images are not merely illustrative. They are part of a visual history whose import we have felt and internalized.

FIGURE 11

Used RPPC, 1912–1915, 8.7 × 14 cm.

Second, the dog also adds a compositional element that enriches the photograph. Even if all of these pictures could have been taken without the dog, many of them would be diminished, if not disintegrated, by the loss of the dog. In figure 11, it is impossible to imagine the man without his dog. They are entwined, and the note scribbled on the back does nothing to disentangle or separate the two: “Who is this” could refer to the man, the dog, or both. They belong together. Similarly, the exuberant energy of the toddler and her setter in figure 12 makes a captivating image. Either subject could have stood alone for a portrait and made a pleasant image, but their shared energy animates the portrait in a way that neither could have accomplished alone. Obviously, not all photographs with dogs will offer interesting aesthetic or compositional dimensions. Sometimes the living dog is merely a prop, and eliminating the dog from the picture would not change the overall suggestion of the image, although even that comment tells us something about the sitter, as we learn more about the use of the dog in photographic composition.

FIGURE 12

Cabinet card, 1900–1910, 8.8 × 12.2 cm. Photograph by Hatton. Lansing, Michigan.

Third, seeing dogs in pictures enhances our sense of the humanity of our forebears, especially when we consider how messy and even fragile an enterprise dog ownership was at the turn of the century. Flea control, now a matter of a monthly dose between the shoulder blades, would have been a constant issue in the spring and summer months (and in the South, all year round). Distemper and rabies vaccines were not developed until the late 1920s, so that loving a dog (as opposed to simply owning one) would have subjected one to predictable and periodic loss.

Fourth, unlike any other animal, “home is where the dog is.”35 Certainly in American photography, the dog becomes part of the patriotic iconography embracing all the meanings of home—family, fidelity, comfort, protection, nurturance, and love—as well as symbolizing some of the less palatable meanings of home and family—domination, subservience, and violence. Generations of American politicians have used dogs to validate their claim to an upright character, and so an entire nation can debate what kind of dog the president will chose, because dogs are such an important symbol of everything we say we hold dear.

Finally, the dog invites our participation in a moment otherwise largely inaccessible to us. One of the features of antique photographs is the stiffness of the unsmiling subjects. For example, my Grandma Morey was suspicious of the camera, and not always very supportive of Grandpa’s interest in the new instrument. She is famous in family pictures for crimping her lips instead of smiling, and I was given to understand that she was vain, and didn’t think she looked good smiling. But histories of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photography suggest that people were advised that only a lower-class person would be so vulgar as to show his or her teeth in a photograph. A slack, open mouth suggested a slack character. So Alice White, born in 1897, may simply have been following the conventions of the day. The commanded smile is a later development in the history of photographic conventions, and has become a conventional artiface. But for contemporary viewers the smile establishes a friendly, welcoming moment. Smiling people are inviting, opening the doors so that we can easily see ourselves joining those scripted moments around the birthday cake, graduation ceremony, or family picnic table. Without the smile, there is no implicit welcome that speaks to us.

I suggest that the dog is the missing smile in the photograph. The strangeness of our ancestors’ clothing, homes, and manners is normalized by the dog, who, in the photographic moment, seems timeless. Dogs sprawl, sleep, pant, and wriggle, just as they always have. And because we recognize dogs as familiar and valued, the dog smiles to us that these people are not so different from us, and that despite their stiff demeanors and strange clothing, they too might have joined the dog on the floor in a game of tug-the-sock. Whether we meant for them to be in the picture or not, dogs are unselfconsciously themselves, speaking across time and cultural boundaries. By presenting their dogs, our forebears open the door and welcome us in.