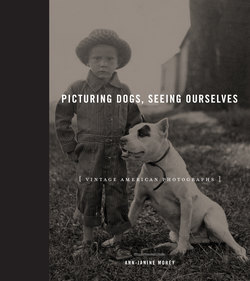

Читать книгу Picturing Dogs, Seeing Ourselves - Ann-Janine Morey - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

[SOME WORDS ABOUT THE PICTURES]

I began my career as a religious studies professor, but I’ve been an English professor for the last twenty years, so it’s safe to say that no matter where I’ve been in my career, I’ve lived by words, if not “the word.” I never planned on writing a book about pictures, although I have always had dogs, as have my sister and my brother, the latter of whom is the anthropologist who documents the funerary tenderness between dogs and ancient human civilizations (see the introduction). Yet my own family history I pretty much took for granted until one day—sometime in the mid-1990s—I was reading a library book and a picture fell from its pages. It was a trimmed snapshot of a woman sitting on the grass with her dog, probably dating from the 1920s. The original is sepia toned, which adds to the gentleness of the image, but I was pleased with the way in which the woman was gazing so thoughtfully at the dog, who is occupied with something beyond the frame but leaning comfortably against her. I kept the picture because I liked it, not anticipating how much I would later enjoy the symbolism of having the image come tumbling from the words.

Several years later I was rummaging around in an antique store and decided to flip through the photo postcards. I came across two more pictures. One of them is a small image of a pretty young woman who has posed herself and her dogs for a picture. She’s thoughtfully provided not only a chair for one dog but also a blanket to cushion the chair for the alert dog, and her proprietary hand indicates her ownership of the moment. She is proud in her stance, and her handsome dog seems to mirror her posture. Her dress is a functional work dress, and the outdoor setting suggests a farm or even frontier setting.

The other is “Buster,” so identified by the good-humored message on the back, addressed to G. M. Sneed of McLeansboro, Illinois: “This is Buster Dimond [?]. what do you think of him. Lovingly, Sister Sue.” This portrait reminded me of one of my own family dog pictures, and in pursuing my topic, I discovered that it was common for people in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century to produce solo portraits of their dogs, who sometimes became the subject of a postcard message. Charmed, I began collecting, and in doing so found an unexpected way not only to discover my own visual intelligence but also to redeem a childhood of reading beloved dog stories at the same time. In time, the words—stories—took a back seat to the photographs, which was another unexpected outcome for me.

FIGURE 1

Unused RPPC, 1908, 5.5 × 8.7 cm.

I’m not the first person to collect antique photographs of people and their dogs. Barbara and Jane Brackman, for example, present a collection of informal and formal photographs, pairing their collection with comments about dogs over time. Their work testifies to the appeal of the human-dog relationship, but the appended comments about dogs rarely have any historical connection to the picture at hand. Libby Hall has produced several beautiful volumes of pictures that are worldwide in their scope, but she presents her pictures solely to document the dog love of previous generations, not as artifacts suggestive of further meaning. The same is true of a similar collection offered by Gary Eichhorn and Scott Jones. Moreover, Hall and Eichhorn and Jones prefer formal portraits, which means that their collections have a fairly narrow social dimension as well.

FIGURE 2

Buster. Used RPPC, 1911, 8.7 × 13.7 cm.

Other photo collections offer a much wider social perspective in terms of white owners particularly. Donna Long offers some historically pertinent information about the various dog breeds that appear in her collection of cute kids and dogs. Cameron Woo gathers his collection—Photobooth Dogs—by location. Catherine Johnson’s book Dogs presents more than four hundred cabinet cards, cartes de visite, and snapshots of people and dogs, coupling the photos with ahistorical quotations in honor of dogs. Ruth Silverman’s The Dog Observed: Photographs, 1844–1983 begins with antique photos where we often don’t know the photographer, but focuses on images by famous photographers as we move through the volume. The purpose of these collections is to demonstrate the enduring affection between people and dogs. For example, Barbara Cohen and Louise Taylor gathered portraits in Dogs and Their Women to celebrate “the loving relationship that women have with their dogs,”1 and they couple their portraits with comments about the dog from the woman in the picture. In fact, all of the editors of these collections suggest the same goal, sharing their enjoyment of these pictures as any dog enthusiast would. They aren’t pursuing historical accuracy in these collections; they are documenting emotional and spiritual commitment over time.

This also means that no work considers what the dog in the photograph might mean beyond the visual surface of the subject. My work picks up from this documentation in order to delve more deeply into the cultural revelations that might arise from considering a collection as a visually expressive vehicle of cultural values. For example, there is a photograph toward the back of Johnson’s book of two white people in a doorway with a group of Great Danes. The dogs are facing the white people, clustered around them as if looking for a treat. To their left is a black woman dressed in white (perhaps a maid’s uniform) and a black man with his hat in hand. If this image were part of my collection, I’d probably suggest that the white people are displaying their possession of the dogs and the hired help. Perhaps there is other information about the photo that would clarify the relationships of the people, but in its absence, the visual information that I present in chapter 3 urges us to attend to these racial dimensions.

No archive is value neutral, and this statement certainly includes one as modest as what I present here. Paula Amad comments on the seeming objectivity of archival collections, noting that we should be aware of how much an archive is “produced, ideological, and often deeply personal.”2 To illustrate from the Picturing Dogs collection, in order for these photographs to be available, their originators or owners had to have the means of preserving them. So we have many more artifacts from middle- and upper-class subjects than from the working class and poor. I had to have the time to look for them and the financial means to purchase them, both class-based elements. The process of selection was subject to my liberal arts educational framework, along with my class, gender, and racial biases. I gravitated toward pictures of women, for example. And then my intuitions were in play as well. I often purchased a photograph without being able to say at the time why it seemed important. But as the collection grew, so did my vision of what was required to tell the emerging story.

Other factors that shaped the collection may also be significant. In contrast to some of the sources mentioned above, I prefer informal poses to formal studio portraits, although I use both. Unlike a collector, I have not been concerned with acquiring a pristine image, feeling that a battered image was also part of the record, although I have sometimes improved the clarity of the digital image with Photoshop. My collection was sometimes limited by cost, and since I began collecting, most of the traffic in photographic images has been rerouted through the Internet. It is increasingly rare to find a good image by canvassing antique stores.

The cost of clean images in cabinet-card or carte-de-visite format (I discuss the various image formats in chapter 1) can range from $9.99 to $50, with real photo postcards commanding somewhat less. When toys or guns are part of the ensemble, images of people and dogs may cost anywhere from $75 to $200. Photographs of African Americans with dogs are rarer, and an image in good condition can sell for several hundred dollars. In the case of material on African Americans and dogs, I have looked at many more images than I own, including major collections of African American photography housed at Yale University and the New York City Public Library.

Over the past decade, I’ve gathered more than three hundred antique photographs of people with their dogs. While the collection ranges from a possible early date of 1860 to the mid-twentieth century, most of the images date from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When possible, I indicate dates or decade frames, but these attributions are necessarily tentative because very few of the pictures are actually dated. The easiest photographs to date are the real photo postcards, because the stamp box and lettering, along with postmarks, can place the card within several years of its origin. There are also guidelines for dating cabinet cards and cartes de visite based upon the thickness, cut, and embellishment of the cards, although these standards are difficult to use without expert guidance. In most cases I have been content with identifying a decade, unless there is something particular to an image that narrows the time frame. Sometimes clothing can be helpful, and I have used several sources to better identify the time frame and the content of the image itself, relying largely upon Joan Severa’s beautiful presentation in Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion, 1840–1900, supplemented by Olian, Blum, Dalrymple, and Harris.3

For dating snapshots, I used my dad’s collection of family photographs. By comparing sizes and formats with dated images in his collection, I devised a rough template for approximating dates. For those pictures, not only was clothing helpful, but the appearance of the family automobile also indicated a rough time frame. In addition to the obvious vagaries and uncertainties of dating, most of my photographs come from persons and contexts unknown, so any conclusion about a single photograph must be taken as suggestion, not fact. Having said that, however, the operating perspective of the book assumes that while no single photograph can have meaning by itself, these photographs do have meaning as a collection. They were gathered randomly at first. I simply bought pictures that appealed to me visually. I took pleasure in looking at them, and in contacting local historical societies in an effort to identify persons or dates. When I discuss the several image formats (chapter 1), I offer some average measurements for each format that include the backing and framing. But in the text, I measured only the image itself and did not include the borders around it or the backing material. The size of each image is given in centimeters for greater precision. What I discovered in the process of looking at the pictures was the cultural force of a shared visual rhetoric. I added to this sense of visual coherence my own childhood reading of dog stories, which, I realized, could illustrate what I was seeing in the photographs. Finally, I consulted a number of authorities in cultural studies, with special attention to scholars working across a variety of disciplines in animal studies. How and why we represent animals—in this instance, dogs—becomes more than a pleasant historical moment when viewed as part of larger cultural patterns. I submit that we can better understand the broad fabric of cultural attitudes and values by looking at the artifacts that have been left behind, and by assembling them in ways that restore at least the public portion of the cultural story that gave them life. I also assert that the role of visual and material culture in shaping and sustaining cultural values and prejudices has yet to be fully reckoned or integrated, so much have we been a people absorbed by words and narrative. Women and African Americans in particular have long been cognizant of the power of visual images to free or constrain a person, and the struggle of identity and self-determination for many people on American soil has been a matter of recognizing that “the field of representation (how we see ourselves, how other see us) is a site of ongoing struggle.”4 While not every discussion in the pages that follow is about cultural struggle, I was astonished by how a topic that had seemed so simple and transparent—pictures of people with their dogs—proved to be far more enigmatic than I could have imagined. Perhaps that enigma can be traced directly to the dog itself, which, in the historical record, is treated with great tenderness and love but also with disgust and cruelty. Because of the dog’s uncanny ability to adapt to our cultural expectations and reflect our emotions, the canine is a mirror of ourselves and our society, and so we have treated and used the dog in ways that reinforce this atavistic ambivalence. Or, to use another metaphor, our relationship with dogs is steeped in all the contradictory and multiple purposes of any great passion, bringing us great comfort and love or great satisfaction in our ability to dominate and hurt. Both elements—comfort and love, domination and hurt—tell the story of our romance with dogs, and this collection of photographs brings us closer to that story in ways that words alone cannot.