Читать книгу Bonsai and Penjing - Ann McClellan - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеchapter one

A National Collection of Living Arts

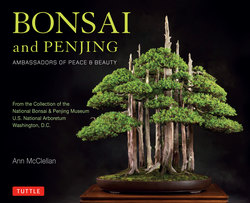

When the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum at the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C. first opened its doors in July 1976, it was the first public museum in the world devoted to the display of bonsai and penjing. With collections representative of the Chinese art of penjing and the Japanese art of bonsai, as well as an evolving North American collection, it is the most comprehensive museum in the world for the display of the natural beauty in trees writ small. The collections are wide-ranging, including some trees that have been handed down from one generation to another, spanning centuries. Even trees that are not old in years are fashioned to look as though they have been aged by time. It is this combination of small and old-appearing that fascinates the imagination, attracting visitors from all over the globe to come and stand in awe before a little landscape in a pot.

Each tree in the collections is a work of art and has a story to tell. It is these stories that add a deeper dimension to a viewer’s experience of each tree. Each was created by one artist, some of whom are legendary. These artists share the skill and eye to work with the small trees, creating works of art that capture the essence of nature’s beauty and offering viewers a different way to perceive the mystery of life itself.

In addition to highlighting several of the collections’ masterpieces, this book explores the global trends, especially the West’s fascination with all things Asian, which culminated in the creation of the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum. It also explores the roles bonsai and penjing have played in the highest levels of international diplomacy as ambassadors of beauty and peace.

The small trees’ role as ambassadors began centuries ago when the Chinese art form called penjing was embraced and enhanced by the Japanese, along with other Chinese arts like calligraphy. In Japan, the art form was called bonsai (pronounced bone-sigh), which means “tray planting.” Bonsai now has come to refer to all diminutive trees and plantings in containers no matter what their origins are. Historically and today, the goal of both art forms is to distill and evoke nature’s magnificence and grandeur into distinctive miniature living trees or compositions.

To become a bonsai or penjing, a tree or plant with a woody stem is chosen for its natural characteristics and for its potential form. Its roots are trimmed to reduce its size and its branches are cut and wired to grow into the desired shape. Most bonsai and penjing artists have an ultimate view of the tree in mind, which they enhance with specially chosen trays or pots, the same way other artists choose frames to set off their work. The process of the tree growing into the artist’s intended shape can take years or decades or even centuries.

A Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’) from Japan, a Garden Juniper (Juniperus procumbens ‘Nana’) from America, and a Cork-bark Pine (Pinus thunbergii Corticosa Group) from China represent the museum’s major collections.

Koinobori or carp kites celebrate Children’s Day on May 5th in Japan, but at the museum they delight visitors all summer long.

CHINA

Ancient China was a highly cultured, complex civilization with a myriad of different aesthetic expressions, ranging from scroll painting to architecture, and it included penjing. In the late seventeenth and into the eighteenth centuries, foreign interest in Chinese arts and goods reached a peak. It led to a fashion trend called chinoiserie, fueled by European and North American colonists’ demand for Chinese tea, silks and decorated porcelain. The fervor for all things Chinese included Chinese-style pavilions and pagodas, which were added to gardens.

A Chinese blue and white hand-painted porcelain dish from 1790–1840, 4.13 x 25.08 x 20 cm, exemplifies the idealized landscapes of the East popular in the West at that time.

After centuries of limiting commerce, the Chinese began to promote trade by participating in world’s fairs in the nineteenth century, such as the 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia and the 1915 Panama-Pacific World Exposition in San Francisco. War in the world and China’s own internal turbulence prevented them from exhibiting again until the 1982 Knoxville World Expo. After President Richard M. Nixon visited China in 1972, there was renewed interest in Chinese arts in the United States, including public Chinese gardens. Interestingly, Chinese gardens were created in Canada at the same time.

The Chinese art form of penjing—the art of creating miniature landscapes on trays, sometimes with plants alone, sometimes with rocks and plants, or other times with rocks only—may have played a role in China’s presentations at the world’s fairs. Where it surely had an impact at an earlier time, however, was in Japan.

| Chinese Gardens in North America after 1980 | |

| 1981 | Astor Chinese Garden Court, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York |

| 1986 | Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada |

| 1990 | Montréal Botanical Garden, Montréal, Québec, Canada |

| 1996 | The Margaret Grigg Nanjing Friendship Garden, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, Missouri |

| 1999 | Chinese Scholar’s Garden, Snug Harbor Cultural Center, Staten Island, New York |

| 2000 | LanSu Chinese Garden, Portland, Oregon |

| 2008 | The Huntington, San Marino, California |

A 19th century Japanese woodcut print, American merchant delighted with miniature cherry tree, 35 x 23 cm, shows a man admiring a bonsai, possibly thinking of his wife.

JAPAN

Over centuries, many elements of Chinese civilization migrated eastward to Japan, ranging from the concept of a pictographic alphabet to the tea ceremony. Typically, the Japanese would embrace a Chinese model, then refine it over time to suit their own culture’s aesthetic sensibilities. Some say this trend reached an apex of expression with the importation of Zen Buddhism in Japan in the fourteenth century, crystalizing during the following centuries into forms familiar to us today. The Chinese art form of penjing is a paradigm of this trend. Penjing arrived in Japan with other Chinese arts, then evolved into the more highly codified geometric and controlled art form of Japanese bonsai.

Also following the Chinese pattern, Japan became the new source of Asian inspiration after its opening to expanded foreign trade by Commodore Matthew C. Perry in 1854. Called japonisme, this infatuation in the West with Japanese style and design, especially lacquerware, textiles and woodblock prints, emerged towards the end of the nineteenth century and into the beginning of the twentieth. It was bolstered by Japan’s own efforts to expand awareness of its country and wares through participating in world’s fairs and expositions, often highlighting gardens and plants.

Like China, Japan exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial International Exposition of 1876. The Japanese presentation included a garden, which featured a pavilion with a bonsai display. Bonsai were also shown at Japan’s exhibition at the Chicago World’s Fair in Illinois in 1893, and at the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in St. Louis, Missouri in 1904. Japan also had a significant presence at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, California in 1915, with an exhibit area more than twice the size of China’s. Once again, bonsai were shown, and one tree from the Exposition is known to survive to this day—the Domoto Trident Maple now at the Pacific Bonsai Museum in Federal Way, Washington.

THE UNITED STATES

At the same time that Japan was creating Japanese gardens for world’s fairs and expositions, private individuals began to create Japanese-style gardens around the United States. The Japanese Hill and Water Garden at the Morris Arboretum near Philadelphia, the Japanese Garden at The Huntington in San Marino, California, and the Japanese Garden at Maymont in Richmond, Virginia, were created before World War I as private gardens, which were later opened to the public. The Japanese Hill-and-Pond Garden at the Brooklyn Botanic Garden was a public garden from its opening in 1915.

While many people were introduced to Japan through its participation in international fairs and expositions, others made the long journey to the country itself and discovered its distinctive culture in person. Among the individuals who traveled to Japan were the Honorable Larz Anderson and his wife Isabel. Anderson served as Ambassador to Japan under President William Howard Taft, returning to the United States in 1913. While in Japan, the Andersons purchased bonsai at the Yokohama Nursery Co. for their home in Massachusetts, and later bequeathed them to the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, where some can be seen today.

Ambassador Larz Anderson bought bonsai from the Yokohama Nursery Co. in Japan in 1913. Later, the company exhibited at the 1915 Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

| Select Japanese Gardens with Bonsai in North America | ||

| Date Created | Bonsai Added | Location |

| 1876 | Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | |

| 1894 | Japanese Tea Garden, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, California | |

| 1911 | 1968 | Japanese Garden, The Huntington, San Marino, California |

| 1911 | Maymont Japanese Garden, Richmond, Virginia | |

| 1915 | 1925 | Japanese Hill-and-Pond Garden, Brooklyn Botanic Garden, Brooklyn, New York |

| 1918 | Hakone Estate and Garden, Saratoga, California | |

| 1949 | 1976 | Asian Collections and National Bonsai & Penjing Museum, U.S. National Arboretum, Washington, D.C. |

| 1957 | 1957 | Japanese-style Garden and Bonsai, Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens, Washington, D.C. |

| 1958 | Shōfūsō Japanese House and Garden, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | |

| 1960 | Japanese Garden, Washington Park Arboretum, Seattle, Washington | |

| 1960 | Nitobe Memorial Garden, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada | |

| 1961 | Japanese Garden, Bloedel Reserve, Bainbridge Island, Washington | |

| 1963 | Portland Japanese Garden, Portland, Oregon | |

| 1965 | Japanese Garden, San Mateo Central Park, San Mateo, California | |

| 1972 | 1977 | Sansho’en (Garden of the Three Islands)/Elizabeth Hubert Malott Japanese Garden, Chicago Botanic Garden, Glencoe, Illinois |

| 1973 | Japanese Garden, Fort Worth Botanic Garden, Fort Worth, Texas | |

| 1974 | Japanese Garden, Buffalo, New York | |

| 1974 | Nishinomiya Garden, Manito Park, Spokane, Washington | |

| 1976 | Japanese Garden, Normandale, Minnesota | |

| 1977 | Seiwa’en (Garden of Pure, Clear Harmony and Peace), Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri | |

| 1978 | Anderson Japanese Gardens, Rockford, Illinois | |

| 1979 | 1987 | Ordway Japanese Garden, Como Park Zoo, St. Paul, Minnesota |

| 1979 | Shōfū’en (Garden of the Pine Winds), Denver Botanic Gardens, Colorado | |

| 1984 | Suihō’en (Garden of Water and Fragrance), Donald C. Tillman Water Reclamation Plant, Van Nuys, California | |

| 1985 | Seisuitei (Pavilion of Pure Water), Minnesota Landscape Arboretum, Chanhassen, Minnesota | |

| 1988 | 1985 | Japanese Garden, Montréal Botanical Garden, Montréal, Québec, Canada |

| 1988 | Tenshin’en (Garden of the Heart of Heaven), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts | |

| 1996 | Rohō’en, Japanese Friendship Garden, Margaret T. Hance Park, Phoenix, Arizona | |

| 2001 | 2001 | Roji’en (Garden of Drops of Dew), Geroge D. and Harriet W. Cornell Japanese Gardens, Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens, Delray Beach, Florida |

| 2001 | 2001 | Garden of the Pine Wind, Garvan Woodland Gardens, Hot Springs National Park, Arkansas |

| 2015 | 2015 | DeVos Japanese Garden, Frederik Meijer Garden & Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, Michigan |

The “Specimens of the famous Japanese minimized trees, above 100 years in pots” featured in the Yokohama Nursery Co. Catalog of 1898 are similar to bonsai brought from Japan by Larz and Isabel Anderson.

A Yokohama Nursery Co. Catalog from 1903 features flowering cherry blossoms from Japan on its cover to entice overseas plant buyers.

When he visited Japan in 1901, renowned plant explorer David Fairchild photographed a man creating a bonsai at the Yokohama Nursery Co.

David Fairchild was another visitor to the Yokohama Nursery Co. in Japan where he photographed a bonsai being worked on. A plant explorer, he and his wife Marion played key roles in the 1912 gift of more than 3,000 cherry blossom trees from Tokyo to Washington, D.C., the precursor of the Bicentennial Gift of bonsai from Japan. Fairchild introduced many hundreds of plants new to the United States, including soybeans, mangoes and nectarines, and he was a leading proponent of the creation of the U.S. National Arboretum in Washington, D.C.

Interest in Japanese-style gardens and in bonsai languished during World War II when anything related to Japan was considered suspect. Following the war, there was a resurgence of interest because Americans returning from Japan were eager to introduce their compatriots to the expressions of natural beauty they had experienced there. Bonsai enthusiasts who had hidden or given away their collections during the war brought them forward or reclaimed them. Some formed clubs while others taught bonsai techniques, leading to a broadening of awareness of the art form. Japanese-style gardens also enjoyed renewed popularity after the war, encouraged by Japan which sought to strengthen bonds of peace and friendship. Some of these gardens were developed privately and some were public, often created through “sister city” relationships.

A glass lantern slide by Francis Benjamin Johnston in 1923, 8.26 x 10.16 cm, shows The Huntington’s moon bridge five years before the gardens were opened to the public.

The Japanese Hill-and-Pond Garden of the Brooklyn Botanic Garden is one of the oldest Japanese-inspired gardens in the U.S. It opened to the public in 1915.

Not every Japanese-style garden or arboretum could include bonsai because they require a major commitment of financial and personnel resources due to their need for daily care and skilled maintenance. The Brooklyn Botanic Garden was one exception: it was given a bonsai collection in 1925. The Arnold Arboretum was another when it received part of the Larz Anderson collection in the 1930s.

Other major public gardens added bonsai to their collections after World War II. The Longwood Gardens bonsai collection began in 1959 with 13 trees purchased from Yuji Yoshimura, who also played a pivotal role in the development of the national collection at the Arboretum. The Huntington collection began in 1968 with the gift of a personal collection. The National Bonsai & Penjing Museum itself was founded to house the Bicentennial Gift of bonsai from Japan to the United States in 1976. A year later, the Chicago Botanic Garden opened its bonsai collection, followed by other major collections across the country and in Canada.

Today, the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum is proud to show exemplars of the finest bonsai from around the world, brought together to allow visitors to experience nature’s most delightful and enchanting qualities as expressed in these living works of art.

SPOTLIGHT ON Dr. John L. Creech

Distinguished horticulturist and plant explorer, Dr. John L. Creech (1920–2009) was Director of the U.S. National Arboretum from 1973 to 1980. A Rhode Island native, Creech’s creativity and gardening skills kept him and 1,500 fellow prisoners of war alive in remote Poland during World War II. Returning to civilian life in 1947, Creech joined the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Office of Foreign Plant Exploration. In 1955, he made the first official American plant-hunting trip to Japan after World War II, searching for plants to be used for food crops, pharmaceutical research or ornamental purposes. While there, he met Yuji Yoshimura, leading to Yuji’s eventual move to the U.S. where he played an important role in bringing bonsai to Washington, D.C.

An enthusiastic and successful plant hunter, Creech was involved in the introduction to the United States of new varieties of camellias, azaleas, daylilies, chrysanthemums and sedum. Most famously, he found and collected the seeds of a Crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia fauriei) on the remote Japanese island of Yakushima, which became the source of powdery mildew resistance in the modern crapemyrtle hybrids developed at the U.S. National Arboretum.

When Dr. Creech became Director of the U.S. National Arboretum in 1973, he began to imagine what role the arboretum might play in the nation’s Bicentennial Celebration in 1976. Inspired by David Fairchild’s instrumental role in the gift of flowering cherry trees from Tokyo to Washington in 1912, and relying on his own experience and contacts, Creech thought the gift of a few bonsai from Japan might be possible. The rest is history, as they say, well told in Creech’s book, The Bonsai Saga, excerpts from which are included as Chapter Seven of this book.

John Creech and Masaru Yamaki in the Japanese Pavilion, visiting Yamaki’s Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora ‘Miyajima’), in training since 1625 and the oldest tree in the museum’s collection.

Dr. John Creech shown with a Crapemyrtle (Lagerstroemia fauriei) resistant to powdery mildew, grown from seeds he brought back from a remote Japanese island.

A Japanese Red Pine (Pinus densiflora), given by Emperor Hirohito, was permitted to be at the White House when he and Empress Nagako joined President and Mrs. Ford there for a reception preceding a state dinner in 1975.