Читать книгу Bonsai and Penjing - Ann McClellan - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

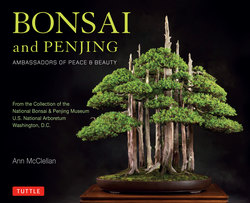

Оглавлениеchapter two

Presidential Connections

Bonsai from Japan and penjing from China, along with the related art form of viewing stones, have served as diplomatic gifts at the highest possible levels, involving presidents, emperors, kings, ambassadors and foreign dignitaries. Why? Because these beautiful trees and distinctive stones are unique gifts from nature, expressions of a country’s culture and sophistication, or rare finds from its territory. After their official presentation in the United States, these trees and stones are “honored” by being included in the National Bonsai & Penjing Museum, where they belong to the public and can be enjoyed by everyone.

In the United States, presidents have taken an interest in penjing and bonsai beginning with President Richard Nixon. He was said to have been given a few penjing trees when he visited China in 1972, though none are known to survive. There is a photograph of Nixon with a small bonsai on a credenza in the Oval Office, giving credence to the legend that says he wanted one there at all times.

President Gerald Ford was given a magnificent chrysanthemum-patterned viewing stone, Tsukiyo Kiku or “Mums in the Moonlight,” in honor of the U.S. Bicentennial. This large rock is from Neodani in the Gifu Prefecture of Japan, an area renowned for its chrysanthemum stones, and was donated by the Nippon Suiseki Association. The chrysanthemum is associated in Japan with the emperor and his family, and is an East Asian symbol of long life or immortality.

President Richard Nixon is shown at his desk in the White House Oval Office with a bonsai on a table behind him.

The magnificent “Mums in the Moonlight” viewing stone was a gift to President Ford from the Nippon Suiseki Association in honor of the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976.

John Creech mentions in The Bonsai Saga how the “Mums in the Moonlight” stone came to the U.S. National Arboretum:

There is an enormous and beautiful chrysanthemum stone in the bonsai collection that originally was sent as a gift to President Gerald R. Ford. How it came to be a part of the National Bonsai Collection is an interesting story. In the fall of 1976, Skip [March] and I undertook a collecting trip to Japan to visit nurseries. While there we met several of the donors of the plants and stones in the collection. At one bonsai nursery in Angyo, we were shown a chrysanthemum stone that was to be sent as a gift to President Ford. Several months later, I asked a White House staff member about the stone and what had been done with it. To my surprise, I learned that the crate was in storage until a decision could be made. We had excellent relations with the horticultural staff at the White House, and I suggested that perhaps the place for it was the National Arboretum Bonsai Collection. Our collection had by now received sufficient status so that the stone was duly delivered and became part of the National Bonsai Museum’s collection.

Bonsai and penjing are also used to make foreign visitors feel at home. When President Jimmy Carter and First Lady Rosalynn Carter hosted Japan’s Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda in 1977, a bonsai from Japan’s Bicentennial Gift was requested for the Oval Office at the White House for the visit. In Carter’s welcoming remarks, he noted that the close relationship between the U.S. and Japan after World War II was made possible by “the strength of the Japanese society and also the beauty which has always been characteristic of the arts that exist in the minds and hearts of the Japanese people.” This beauty is exemplified by bonsai.

In 1977, at President Carter’s request, bonsai were brought to the White House from the U.S. National Arboretum to make Japanese Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda feel at home.

Given by King Hassan II, a Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora), in training since 1832, was presented by the Moroccan ambassador to Mrs. Reagan in 1983.

A tiger-stripe stone from Japan’s Setagawa River was presented to President Clinton during his visit to Japan in 1998, a Year of the Tiger according to Asian calendars.

A gift from Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda, this Trident Maple (Acer buergerianum), in training since 1916, is a root-over-rock style, reflecting how trees sometimes grow over rocks in nature.

John Creech also mentioned President and Mrs. Carter and their appreciation for bonsai in The Bonsai Saga:

The bonsai collection was now on the State Department list of places to bring foreign dignitaries. First Lady Rosalyn Carter visited the Arboretum several times with such visitors, once with Ambassador Togo’s wife. As a result, the White House used the collection to good advantage when Japanese Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda later met with President Carter.

The White House staff was informed that Prime Minister Fukuda had a yew tree in the bonsai collection and asked us if it would be possible to have the prime minister’s bonsai sitting on the credenza behind the president’s desk during their conversation in the Oval Office. We were delighted to comply with the request, and Skip March was elected to take the bonsai to the White House. With plant in hand, he was ushered into the Oval Office with lightning speed to place the plant on the credenza behind the president’s desk. But in the location where Skip needed to place the bonsai, there was a model of the historic USS Constitution under a glass dome. The ship had to be relocated, and this required approval from the Navy. But Skip prevailed and the bonsai was set in place.

The next thing he knew President Carter entered the Oval Office just prior to receiving the prime minister on the South lawn. Skip was introduced and had a brief conversation with the president. President Carter suggested that perhaps the tree could stay at the White House. Skip said very diplomatically, “no, it might die if kept indoors.” Then President Carter suggested that perhaps two trees could be left if alternated. Well that idea did not go over very well with Skip and he again politely said, “no, Mr. President,” and the president desisted, much to the relief of the White House Garden staff. Then the president went off to greet the prime minister, and Skip had the opportunity to watch the ceremony from the Blue Room.

Saburo Kato (far left) joined Prime Minister Obuchi and Mrs. Obuchi and President and Mrs. Clinton in admiring the Ezo Spruce at the White House in 1999.

Bonsai were also on view at the White House when Prime Minister Keizō Obuchi visited President William Clinton and First Lady Hillary Clinton in 1998. Saburo Kato, Chairman of the Nippon Bonsai Association and a key figure in the donation of the Bicentennial Gift from Japan, was present, accompanying the prime minister, his bonsai student. Obuchi’s gift to Clinton in 1998 of an Ezo Spruce collected by Kato in the 1930s and a tiger-stripe stone given by former Prime Minister Hiroshi Mitsuzuka were displayed when Clinton visited Japan. The stone, honoring 1998 as a Year of the Tiger in Asian calendars, is from the Setagawa River area in the Shiga and Kyoto prefectures.

Bonsai from the museum again graced the White House when President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush hosted a dinner honoring Japan’s Prime Minister Junichirō Koizumi in 2006. A Eurya (Eurya emarginata), in training since 1970, served as a focal point in the Blue Room, while an Ezo Spruce (Picea glehnii) and a Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora) were placed elsewhere.

Other nations also use bonsai as the highest level of diplomatic gifts. His Majesty King Hassan II of Morocco gave President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan two Japanese bonsai from his personal collection in 1983. The king’s Japanese White Pine (Pinus parviflora) survives to this day and has been in training since 1832.

The United States also uses trees as national gifts. In April 2012, 3,000 dogwoods were given to Japan in honor of the centennial of the gift of flowering cherry trees from Tokyo to Washington, D.C. The gift was announced by Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton at a dinner for Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda held at the National Geographic Society. The dogwoods were selected by plant geneticist Richard Olsen, now Director of the U.S. National Arboretum, who took into consideration the soil conditions, temperature ranges and insect pests for the trees to survive in Japan. One thousand dogwood trees were planted in Tokyo and another thousand in the Tohoku region that had been ravaged by the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster in 2011. The remaining thousand were planted at schools and other organizations throughout Japan. The State Department specifically requested that Saburo Kato’s Ezo Spruce be exhibited at the dinner, a beautiful reminder of the power of trees and other living art forms to be symbols of peace and international friendship.

President Clinton and Prime Minister Obuchi flank Saburo Kato in the Blue Room, admiring a California Juniper (Juniperus californica), in training since 1967, and one of the first bonsai to enter the museum’s North American collection.

An Ezo Spruce (Picea glehnii), in training since 1925, was carried on a traditional four-handled tray for its return from the White House to the museum.

Eurya (Eurya emarginata), an evergreen shrub native to the seacoasts of China, Japan and Korea, made Prime Minister Koizumi feel welcome in the White House Blue Room.

SPOTLIGHT ON Saburo Kato

Saburo Kato (1915–2008) was a respected, charismatic and influential bonsai master. The son of a bonsai master, he grew up with bonsai from his earliest years. He experienced the grim days of World War II in Japan when even gray water was rationed and many bonsai were planted in the ground to survive. After the war, there was a resurgence of interest in bonsai, driven in part by American GI’s fascination with the miniature trees.

Kato’s leadership of the Nippon Bonsai Association (NBA) included the facilitation of the Bicentennial Gift of bonsai to the U.S. in 1976. In fact, he was instrumental in convincing NBA members to participate by donating trees and coming to the U.S. to teach Americans how to care for the trees properly. He himself came to work on the bonsai in advance of their display at the Dedication Ceremony and returned to the museum on many occasions over the years to give advice on the care of the collection. The museum, in turn, honored Saburo Kato during his lifetime for his invaluable role in making the Bicentennial Gift from Japan a reality by naming one of its gardens the Kato Family Stroll Garden.

In 1989, Saburo Kato founded and served as the first Chairman of the World Bonsai Friendship Federation (WBFF), an organization whose mission it is to bring peace and goodwill to the world through the art of bonsai. Today, the WBFF honors Kato’s memory by sponsoring World Bonsai Day on the second Saturday of each May, and at the World Bonsai Convention held every four years. Kato believed that the spirit of bonsai, bonsai no kokoro in Japanese, was accessible to people everywhere, that by nurturing bonsai anyone could experience how their love and care creates peace and beauty, a feeling that can be extended to all of nature and the wider world.

The Kato Family Stroll Garden honors the long-term support Saburo Kato and his wife provided to the museum and its collections.

Saburo Kato came to America to prune the bonsai in quarantine, preparing them to be displayed at the Dedication of the Bicentennial Gift on July 9, 1976.