Читать книгу Integrity - Anna Borgeryd - Страница 24

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление17

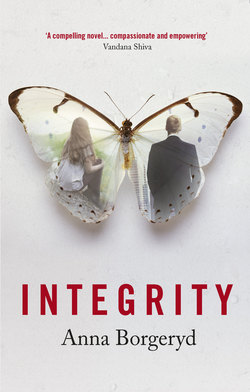

That we need a radically new economic rationality is, at this stage of history, overwhelmingly self-evident. A Green economics – or ecological economics, as I prefer to call it – transforms our destructive economic logic because it subordinates economics to the process of life, rather than, as has been the rule so far, placing life at the service of economics.

Manfred Max-Neef, ‘The Gaia Atlas of Green Economics’

For the first time in his 24-year life, Peter had been rejected by a girl. The unknown feeling was unexpectedly hard to take, and when Cissi appeared and invited him to dance to the big-band classic Just A Gigolo, his mind was still reeling from Vera’s wounding words: ‘Thank you, but I’ll pass.’ Why wouldn’t she even dance with him? What had he ever done to her? Maybe she hated Just A Gigolo? If so, that was something he could sympathize with.

‘How is Vera, really?’ Peter nodded to where Vera was sitting as he guided Cissi out to the dance floor.

‘The City hotel’s Jooohn Travolta,’ sang Renhornen’s vocalist, in a pitch-perfect voice.

‘I actually don’t know. She seems so bitter and strange tonight,’ said Cissi. ‘I wonder if it has anything to do with her…’ She broke off.

‘What?’

‘No, I don’t know. It’s none of my business, but I have a feeling she and her husband are separating. I’ve heard that can make you really unstable.’

‘Ah! No, it probably isn’t easy.’ It was a relief, and Peter struggled not to look pleased. Something else came to mind, making him feel a little ashamed.

‘Yes, and maybe she’s in pain; have you seen how she’s still limping?’ That must be why she didn’t want to! How could he have failed to see that? Maybe because he had been so preoccupied by the fact that he had suddenly realized what she reminded him of: the hair with the flowers, the small, sticking-out ears and the lovely dress made her look like an Elf – the wisest, most just, beautiful and capable mythical being in Tolkien’s world, which had enchanted his boyhood room. A creature that was above human frailties, one that did not fall for simple flirtations, but instead faithfully committed herself for life. Peter’s heart pounded harder, as if he were close to answering his most important question.

‘Well, just because your knee hurts it doesn’t mean you have to be negative about the successes of the welfare project, does it? That’s nuts!’ said Cissi. She felt a vague worry: Was I wrong to choose Vera? She glanced at Peter and wondered what he would say if she asked the question out loud.

The singer in the peppermint-striped skirt and tailcoat could really sing: ‘I ain’t got nobody – nobody cares for me, nobody, nobody…’

Cissi shook off her dour thoughts and focused on the moment, the experience of a party and the glamor of being in the arms of a good-looking man who, surprisingly, knew how to lead a woman on the dance floor, despite the fact that he wasn’t from Norrland. Things could be worse, she thought, and saw the party lights reflecting in her gold dress.

After the rewarding dance with Cissi, Peter returned to Vera, who sat over by the stairs, distractedly watching the half-moon behind the naked birch trees outside.

He knew more now and wanted to talk about the future. ‘Does your leg hurt?’ he asked.

Vera started and looked at him. ‘Yes, you could say that.’

‘Yes, otherwise you would be expected to do your duty as Woman on the project,’ he emphasized with what he thought was a charming, teasing twinkle in his eye. ‘We’re going to have to see how this pans out, us working together and everything…’ He took a step closer.

Vera looked at him as if he were behaving threateningly. She got up smoothly using just one leg. Light and strong, thought Peter. No surprise that an Elf can get up like that.

She looked at him briefly before firmly grabbing the stair rail, turning her back to the party and hobbling down the stairs: ‘Yes, I’m going to have to see how it pans out for me.’

He recognized an unfathomable determination.

And once again, she had turned her back on him and left.

Peter didn’t understand. Every other time when he, uncharacteristically, had been the one to make the advance, he had immediately been victorious. But with Vera… His usual way of making contact didn’t work, exactly when it was important that it did work, just when he had actually met an Elf in real life.

Of course he knew she was a real person – a nurse in her late twenties from inner Västerbotten. But there were several puzzle pieces that pointed directly at something that he longed for, something completely unique. She was beautiful in a hard-to-discover, secret way; she was petite yet strong, wildly curly-haired yet disciplined, superior yet good-hearted, stubborn yet evasive. She was completely unlike all the other women he had known and he sensed instinctively, without really knowing why, that she had something he needed.

When Peter realized that Vera had actually rejected him numerous times, he understood that he had approached things all wrong. The definition of idiocy is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting a different outcome, as his Uncle Ernst used to say.

She was completely different from all the other women he had met. Obviously, he would have to use a completely different approach to get close to her. But different how? There were endless ways to be and do things. How could he get Vera to change her mind? How could he get her to see him the way young women usually did?

A wave of understanding washed over him, and he realized that he needed to get to know his opponent, something his jujutsu instructor had been nagging him about for years. Luckily, Peter, who sometimes had trouble even remembering women’s first names, recalled masses of seemingly unimportant details about Vera. Thus, he had no difficulty remembering that Vera thought books like The Gaia Atlas of Green Economics, Global Women, and State of the World were worth reading. He went to the library and looked for them. The only one that wasn’t out on loan was Green Economics. Peter realized that Vera probably still had the library’s only copy of the other two. In a fit of uncharacteristic ambition, he borrowed other books on welfare and economic development instead.

He called his father and said he couldn’t come to the board meeting next week, because he had too much work to do on the project. Lennart had sounded unexpectedly negative. When Charlie couldn’t come to board meetings it was usually accepted with considerable understanding. And Peter had thought that Lennart must have been a driving force behind him even being asked to join Future Wealth and Welfare. Perhaps Lennart had not realized that the project would take time away from Escape, and maybe even from his usual studies? If so, that was typical of his father. He always wants to have his cake and eat it too, thought Peter, with an irritation that surprised him.

Peter was also surprised that he was even considering reading about welfare. As usual, he found it difficult to read the books from cover to cover. But he read the headings and summaries until he thought he understood the important parts. It was unexpectedly interesting to pit ‘the richest one per cent’ perspective against the argument about welfare and well-being for everyone. The books about welfare on the reference list that Åke had distributed to the members of the project were about the welfare of Sweden as a whole and the welfare of the European Union.

Vera’s brief and jumbled book took a fuzzy global perspective. It was suddenly the welfare of all of humanity, and, as if that weren’t enough, even the whole planet’s. In fascination, Peter realized that it was fully possible that the scrawled pencil notes in Green Economics were Vera’s. He therefore made sure that he read everything that was circled, marked and underlined. It started with a quote from some Manfred in the preface, which claimed that we needed to change economic logic. As if logic can be changed just like that! Either it’s logical, and then we already know it, or it’s illogical, thought Peter.

Then came a depressing list of complaints. The Industrial Economy. Rape of the Earth. Exploitation of Women. Destruction of community. Disposable people. Money in trouble. Catalogue of shame. And finally, the question, ‘All for what?’ to which the response was, ‘Above the poverty level, the relationship between income and happiness is remarkably small.’ The richest one per cent who go on Great Escapes would beg to differ, thought Peter, remembering the classic line that people can say what they want about money and happiness, but it was better to cry in a limousine than a bus.

No wonder she’s bitter, if she spends her time reading stuff like this!

He skimmed the pages restlessly and read a clearly circled passage that claimed that half of the world’s population did two-thirds of the world’s work, earned one tenth of all income and owned less than one per cent of all its assets. It was referring to women.

Suddenly he realized how wrong it had been when he said that Vera was expected to ‘do her Duty as Woman in the project’. For him it had been a humorous way to offset the deeply private humiliation of asking someone to dance and getting a no. He realized now that there was a significant risk that, for Vera, it sounded like he was demanding that she conform to a World Order. An order which, if she agreed with the stuff in this mixed-up book, in her eyes put unreasonable demands on women for a remuneration that was entirely too small. Peter also understood that, at least for her, it was a completely different and worse type of humiliation. And, above all, it wasn’t his. With the social gifts that his mother’s nurturing had honed in him from boyhood, Peter knew that one could joke about one’s own humiliation, but never about other people’s.

Peter put down Green Economics. If he carried on reading stuff like this, would he become as gloomy as Vera? And even if Peter was strangely drawn to her, despite that unattractive quality, it certainly wasn’t something he aspired to himself. He lay a long time with his hands behind his head and thought. This could be a really good game. He imagined how he and Vera would debate, and how he would convince her that her pessimism was exaggerated. He was satisfied. Yes, half an hour with Vera’s book had done the job. He thought he understood more about why she was like she was, and how he could get her to change. He was like a spy after a successful mission. He had broken a code and entered, in order to dig out decisive information. He turned off the light with the satisfied feeling of having done his homework.