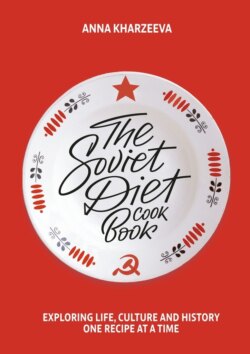

Читать книгу The Soviet Diet Cookbook: exploring life, culture and history – one recipe at a time - Anna Kharzeeva - Страница 16

13. The breakfast all Russians love to hate. Mannaya kasha (semolina porridge)

ОглавлениеThis week, my breakfast meal was mannaya kasha or semolina porridge, affectionately known as manka. This is the breakfast that Soviet people really had every day, unlike the one described in the Book.

These days, however, I would never serve it for breakfast if I wanted people to speak to me again. Not that everyone hates it, but your chances of at least half the people in the room having a reaction of: “anything but this, I can’t believe this is happening to me” when served this meal are very high.

The reason for such a reaction is that manka has always been considered the best breakfast meal for kids, and it is served everywhere – at home, in preschool, at school, at the office cafeteria… It’s a milky gooey mass on a plate that, if not quite cooked right, or not very hot, turns quickly into… a milky gooey mass that is slightly less edible. It is a real life nightmare for many.

In a famous short story, “All Secrets Become Known,” a boy has to eat his manka or he won’t be allowed to go to the Kremlin. He hates the stuff and pours it out the window and straight on to someone’s hat. I still remember the drawing in the book with the porridge coming off a tall skinny man’s hat, nose and coat. I know many people who would say that’s exactly where it belongs.

Lucky for me, I actually like manka. Granny will make it for me on the odd occasion and I’m always happy to have it. I even ordered it at a restaurant recently! I loved watching people’s reaction when I told them what I ate. I think I narrowly avoided being put in a mental institution.

Even though I have manka every now and again, up to this point, I’ve been able to avoid making it for myself, as I know it’s not easy to keep it from forming lumps and/or burning. I was really focused and trying very hard, yet my porridge didn’t turn out perfectly – it was a little bit burnt, and had a few lumps in it. I ate it anyway.

Granny says she was surprised when in a kind of home economics class she conducted at school, a pupil was making manka with cold water. He put the dry manka in the proportion of 2 tablespoons per 1 cup water into cold water and then slowly brought it to a boil. He explained that this way there were fewer lumps. Granny took his advice to heart and makes manka that way to this day.

I also feel grateful to manka, since I recently found out it helped my parents survive. They were both born in 1963, a year in which, according to Granny, “all the food suddenly disappeared from shops.” “There were no grains,” she said. “When your mom was little, I was surprised to find a packet of manka in the shop, and when I took it home, I saw that it had worms and bugs in it. Turned out it was the ‘strategic reserves’ that had been made a while ago and had gone bad.”

My dad’s mother says that when she was pregnant with my father and living in Kursk, she had even less food than there was in Moscow. She would be given some manka as well as some other foods at a special office for women who were pregnant or had young children, and that was a huge help.

It seems to me that unlike we young modern Russians, the Soviet adults stayed loyal to their childhood savior.

“There were carrot, cabbage and beet rissoles with manka for sale in the ‘gastronomy’ sections of restaurants and cafes,” Granny remembers. “They were all very popular.”

Granny’s friend Galina Vasileyvna also shared this story about the ubiquity of manka in the Soviet diet:

“When ‘ptichye moloko’ (bird’s milk) cake first appeared, it would be sold at the Praga Restaurant. It was so popular that you had to put in a pre-order and then wait your turn. Those who didn’t want to wait developed a recipe for it that could be made at home. In it, they replaced the soufflé with manka porridge. The recipe went around the whole country, traveling from city to city.”

I will continue to stay loyal to the meal that kept me, my parents and grandparents full in the mornings – the porridge, not the cake. That would be my Soviet nightmare.

Recipe:

¾ cup milk; 3 teaspoons semolina; ½ teaspoon sugar; 1 teaspoon butter.

Add ¼ cup water to the milk and bring to a boil. When the liquid is boiling, slowly add the semolina, stirring constantly.

Add the sugar and a pinch of salt and cook on low heat 10—15 minutes. Put the butter on top of the porridge before serving.

Granny’s method:

2 heaped tablespoons semolina

1 cup milk or water, or half of each

Sugar to taste

Pinch of salt

Place the semolina into cold water in a pot, slowly bring to boil, add salt and sugar, reduce heat and stir constantly until it thickens up. Serve with jam.