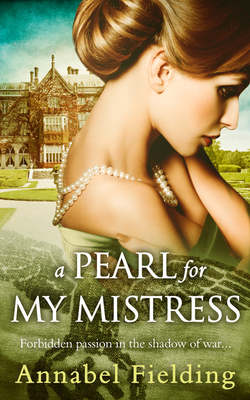

Читать книгу A Pearl for My Mistress - Annabel Fielding - Страница 10

ОглавлениеChapter Three

‘Thanks for taking these napkins, by the way,’ Abby whispered theatrically, as they ploughed their way through the snow. ‘I’d never have finished them on time myself. I’m still drowning in pillowcases.’

The landscape was weighted down with leaden winter twilight. Even after the narrow town streets, so sleepy on Sunday, the silence of the estate grounds always seemed to ambush them.

‘It’s nothing,’ Hester replied and squeezed her friend’s hand slightly. Like hers, it was clad in a coarse black glove, and still managed to freeze into rigidity as they walked from the train station. ‘I couldn’t let you drown in pillowcases, after all. That would’ve been a hideous death.’

The prospect of stuffing her precious hours of freedom with the patching of dinner napkins looked daunting. However, seeing Abigail wasting her hours of sleep away was even more daunting.

‘We’d have to make sure the Crow doesn’t know,’ the redhead continued in the same delighted whisper. ‘Otherwise she’d have a fit.’

‘Why, just because I’m lending you a hand?’

‘These are my duties, after all.’ Abby shrugged with an air of tetchiness. ‘She’s not too glad that we’re mixing so much as it is.’

‘Mixing!’ Hester couldn’t help but laugh. The word had such an air of Victorian aloofness that she couldn’t take it seriously for the life of her.

Not that she was oblivious to the intricate inner structures of the servants’ wing, of course. No one who lived there for more than a week could be. The world beyond the green baize door was as tightly regulated, if not more so, than the world of drawing rooms upstairs.

For instance, Abigail always ate in the servants’ hall, while Hester had to take her dinners in the quiet solemnity of the steward’s room. She heard that both the kitchen maid and Abby herself called it, with the cheerful irreverence, a Pug’s Parlour; the upper servants being, of course, the pugs.

‘Don’t worry,’ Abby said to her then, kissing her cheek. ‘It’s just a sort of tradition. You look nothing like a pug”. She sang the first few lines of ‘You’re the Cream in My Coffee’, a silly little song seemingly unable to leave anyone’s head.

Hester sang the rest of the line, twirling the girl in her arms. A ginger curl swept across her cheek.

Abby proved to be an inexhaustible source of intelligence when it came to this household. She had only worked here for two years, and someone like Mrs Mullet must have regarded her as a clumsy toddler; but for Hester that seemed like a treasure trove of experience.

Abby was still a little bitter about that lecture on thriftiness Mrs Mullet gave her after the housemaid decided to show her a new jumper. However, despite the not-so-affectionate soubriquet, she didn’t harbour any particularly hard feelings towards the housekeeper. Moreover, she schooled Hester in the precarious art of gaining her trust and avoiding her wrath.

At first, Mrs Mullet regarded her with sharp suspicion. According to Abigail, however, it was reserved for all the fresh young servants. Not that Hester felt particularly better for it; on the contrary, she felt her Northern vowels and bad posture more acutely than ever despite all her efforts.

However, in the tight, insulated world of Hebden Hall the new pair of ears was too seductive a gift to be scorned for long. After the cook-housekeeper finally acknowledged, that Hester worked quite well and probably wasn’t going to escape with the silver cutlery, their relationship started to warm.

Mrs Mullet’s memory was an enormous library when it came to the fascinating past of Hebden Hall and its illustrious inhabitants. She had first walked through the corridors of the servants’ wing at the dawn of the century, a shy girl of fifteen who arrived to become a kitchen maid. It was almost impossible to imagine Mrs Mullet shy; but then, it was equally impossible to imagine these quiet, grey halls as the bustling haven of activity she described them to be.

They had a proper housekeeper back then, of course, and Mrs Mullet wouldn’t have dreamt to take her place. In the steward’s room solemn silence always reigned; the upper servants were waited upon by an efficient young footman, and the butler presided over the table.

Now the chauffeur, also doubling as valet, was the only male servant left. It was rational, Hester supposed; after all, one didn’t have to pay women as much.

Mrs Mullet could remember the time, when Her present Ladyship was just gliding through her first Season – tight-laced in a corset, her skirts like pale clouds.

‘They were real ladies back then,’ Mrs Mullet sighed. ‘They never forgot to conduct themselves with proper decorum. Her Ladyship in particular, she always strived to be immaculate. Nowadays young girls are allowed all kinds of debauchery. Not our Lady Lucy, of course,’ she added hastily. ‘She has always been as pure as a lily-of-the-valley. Never smokes, and certainly wouldn’t dream of cutting her lovely curls.’

She scarcely spoke of the other times, of the Dark Ages that started only several years after the joyful celebrations of Armistice. It was a picture Hester had to piece together by details, by curt comments, by throwaway remarks, usually accompanied by a wince.

For instance, how much land the Fitzmartins had to sell to pay the death duties for the late Earl. How the close-knit world of downstairs was chipped away bit by bit, until only a couple of women remained, dwelling in these enormous caverns. How Mrs Mullet agreed to take on the duties of the gone housekeeper in addition to her usual work – only temporarily, of course, until things get better. But they didn’t get better.

Sometimes, they had to pay little Lucy’s governess with milk and eggs from the estate farm.

Hester was often curious as to the whereabouts of enigmatic Mr Mullet amidst all these troubles. She even conjured up a romantic story about his brave sacrifice on the fields of Flanders. However, it turned out that he never actually existed: as years passed by, the cook merely added ‘Mrs’ to her surname as a sign of gravity.

Hester tried to picture her life, to piece together the scrapbook of the decades. Did she ever have a sweetheart? Did she ever have friends outside the servants’ hall? She certainly never had children; that went without saying.

She walked through this door when the Fitzmartins still rode horse-drawn carriages, and had never left since. She lived through the family’s triumphs and carried them through their hardships.

Was that her future fate, too?

No, Hester hastened to assure herself, of course not.

After all, these are different times.

No one would expect her to toil without rest now, and, if she decided to find a better place one day, no one would consider it to be some sort of betrayal.

Surely not.

***

The grounds of Hebden Hall greeted her with silence, as Hester made her way through wet snow. She secretly hoped for March to bring at least a hint of spring and pleasant change; however, the local weather stayed dauntingly predictable.

She was surrounded by unnatural stillness, as if the world was now encased in a giant bell. The only sound Hester heard was the sound of her own heavy breath. Her boots were already soaked, and she cursed the hour when she decided to spend this Sunday exploring the grounds.

The morning had been spent, as usual, in accompanying the family on their obligatory visit to the local church. There Hester sat, gazing at the effigies of the past Earls of Hereford, at their monuments and their plaques. She spent the time contemplating these remains of grandeur.

After they returned to the house, she should have used the chance to pass these rare free hours in warmth and contentment. She could have sat by the fire, written a couple of letters, lost herself in the pages of some good novel …

Hester was almost surprised to discover that she had, in fact, reached her destination.

A mock Roman temple: a folly, erected by one of the Fitzmartins of the past. White and serene, it seemed to have been transported straight from the lush, sunlit shores of Italy and trapped in the damp snow of the English countryside. Hester couldn’t suppress a grin, imagining this monument swishing through the air, like one of the new planes. She stepped inside and touched one of the pillars.

‘Beautiful place, isn’t it?’

Hester almost jumped, startled by the sound of this clear voice. She turned to see a petite figure seated on one of the benches inside the folly. The young woman was swaddled in a plain black coat, and her hand was still hovering over an open notebook. Her fingers, gloveless and starkly white, were visibly rigid with cold.

‘Lady Lucy, you should come back inside!’ Hester exclaimed with fervour she didn’t expect of herself. ‘You can catch a fever!’

‘You shouldn’t worry.’ Lady Lucy clearly didn’t share her anxiety. ‘I’ve been coming here for years on end, and I haven’t caught anything yet. In a way, I’ve spent more time here than I have in my own room. It used to be the only way to convince my father that I am, in fact, improving my health and pursuing the great outdoors instead of languishing in the library.’

Lucy’s smile was friendly, and her tone was nonchalant. However, she pressed the notebook against her chest as firmly as if it contained the secrets of the Empire.

‘Still,’ Hester said without the same conviction, ‘I’m sure there’re a lot of comfortable places where you could work …’

‘Oh, there are.’ The young lady shrugged carelessly. ‘But new thoughts seem to come quicker to me if I walk. The fresh air helps, too.’

She gestured to the bench.

‘Come, sit down.’

Hester obeyed, not without some relief. She got much more tired than she expected while wandering these endless frozen paths.

‘Have you decided to explore the grounds?’ Lady Lucy asked. Her unblinking blue stare always imbued even the most innocent questions with menacing depths.

Hester nodded. ‘There’s so much to see. To be honest, I am still getting lost from time to time.’

‘Oh, don’t worry. I was born here, and I still sometimes manage to find myself in an abandoned Elizabethan pantry. There is certainly much to see,’ she continued. ‘The house resembles a dying beast now, but there’re such fascinating stories lurking behind every tapestry. Although, I must say, not all of them are as smooth and stately as you might be led to believe.’

It was an invitation. Lady Lucy might have looked as composed as ever, but beneath her skin Hester sensed a smouldering desire to share some tale.

‘For example?’ She played along.

‘For example, let’s take the story of origin. The story of how the Fitzmartins even got to inhabit this place.’

The Fitzmartins. Not ‘my family’.

‘It happened during the reign of Good Queen Bess,’ Lady Lucy started. ‘The threat of the Armada had been dispelled only recently, and the country still stood in the grip of fear. People were looking for Spanish spies under their beds. It just so happened that the local landowners secretly kept to the old beliefs and celebrated the Mass in their estate. Some say, they even helped the Catholic priests to escape through their tunnels, although this part was never proven. Not that I find it unlikely,’ she added. ‘After all, these nooks and crannies should have been used for something. Through some efforts, Sir Hugo Fitzmartin – he wasn’t made an Earl of Hereford yet – found out about their secret allegiances and made haste to inform Francis Walsingham, the Queen’s spymaster.

‘As I’ve said, the atmosphere in the country was heady; the family was arrested and tried for their supposed treachery and links with the Catholic powers. Later, they managed to escape to France. Their estates were confiscated, and one of them was used to reward the loyal servant of the Crown, the one who had done so much to avert the danger …’

‘Sir Hugo Fitzmartin.’

‘Precisely. It’s even funny, when you think of it. The history of the noble house, the legacy they preen about so much, started with the story of betrayal and opportunism,’ Lucy’s eyes shone with wicked glee, as if she saw her enemy committing a blunder. ‘If life was as neat as a novel, one day it might even have ended the same way.’

Hester nodded, feeling uncomfortable. Lady Lucy’s speech cracked with such fire, it was impossible not to lean closer.

Hester felt the touch of some unknown grievances, secrets and stories, as one could feel the touch of warmth thrown by a flame.

‘So … are you working on something, my lady?’ she asked, following an association as much as wanting to change the topic.

‘As a matter of fact, I am.’ Lady Lucy barely nodded at her notebook. ‘There is a contract for ten articles, you see, and now I am struggling to find a topic for the seventh one. Such a shame December is long gone – there are endless lists of what one can write about Christmas.’

Hester nodded compassionately. Lucy’s grip on her notebook relaxed almost imperceptibly.

‘Well, strictly speaking, I do have an idea. I’m not sure, however, whether it will interest anyone. Something about the most picturesque Northern sites for motor excursions. What do you think, Blake?’

‘Me? I am not sure I know a lot about motor excursions …’

‘Oh, there is nothing complicated in that.’ Lady Lucy waved her hand. ‘One packs some tinned food, takes some friends, jumps into the car, rides away, and returns in the evening. The difficult part is to decide where to go. Everyone knows about Brighton and Bath, but people tend to imagine the Northern counties as one endless grey plain.’

‘Well, they’re wrong!’ That wasn’t probably the most thought-through thing to say, but Hester couldn’t check the hot prick of irritation. ‘There are so many lovely places. I know. I used to cycle everywhere.’

‘Splendid!’ Lucy’s eyes lit up as she moved slightly closer to her maid. ‘You should tell me all about it. Perhaps, I could write about your hometown as well.’

‘I doubt that, my lady. There isn’t much in my hometown that could rival Bath, or even Brighton.’

A look of concern flickered over Lady Lucy’s face, as if a twitch of some invisible flame sent shadows across it.

‘Is there some kind of trouble?’ she asked cautiously. ‘I … I happen to know a little about the situation in this region.’

‘The situation in this region’ – the Earl’s daughter couldn’t have put it more delicately. Hester was used to hearing much less tactful words. The newspaper headlines were, perhaps, a little too dramatic: ‘Places without a future: where industry is dead’. But the situation Lady Lucy was referring to definitely existed; Hester would have to be deaf and blind to argue with that.

Of course, it hadn’t touched her family yet. It couldn’t touch her family. After all, they were always so industrious, so secure, so respectable. Their doorstep was always whitened, and their kitchen range was always blackened. They had a meat joint every Sunday. They even had a piano. Their father hardly ever visited a pub. Their mother took in other people’s laundry to earn some extra money – she used to be a hotel laundress before the marriage, but, of course, no one would retain a married woman at their workplace.

Nevertheless, the spectre of hunger seemed to hover over every doorstep. Even if it was a doorstep scrubbed white.

‘Everything is fine, my lady,’ Hester finally said. ‘You shouldn’t worry about it. My father has a good job at the shipyard …’

‘Aren’t the shipyards among the places worst hit?’

So she knew that, too.

‘They are, yes,’ Hester admitted. ‘But he did retain his job. They are working on one of those giant Cunard liners now.’

Lady Lucy’s face was still tense with concern.

‘I know about these problems,’ she said quietly. ‘About whole families living on the dole. About the Hunger Marches. About youths, walking along railway tracks for hundreds of miles to find some kind of work. And, if you ask my opinion, it is a disgrace to the country.’

Hester couldn’t help but sigh. She didn’t think about these problems in such grand terms; but, come to think of it, there was scarcely a better word.

‘But everything will change soon,’ Lady Lucy continued. ‘Believe me.’

‘It will?’ Hester’s voice must have sounded more sceptical than would be polite.

‘It will. And those responsible for it will answer.’

There was a new, steely conviction in her tone. And, looking at her lady’s smile, Hester felt something like a stir of pity for those responsible.

‘Well, we all hope for the best,’ was all she managed to say.

The sight of Lady Lucy’s frozen, naked hands was still unbearable. Hester reached out and touched her palm; the cold almost burned her.

‘My lady, your hands are icy. If you aren’t writing anything now, I think it’s better to put your gloves on …’

‘Yes, of course.’ Lady Lucy nodded, but didn’t move.

Her hand could have been made of marble.

‘You have such warm fingers,’ Lucy murmured, her voice clear in the snowy silence that surrounded them.

Hester barely dared to stir. It was akin to holding a fragile bird in her hand.

Indeed, she barely dared to breathe, as if too great a sound, too brash a movement, could upset some precarious balance and get the universe falling down on their heads.

But she couldn’t resist moving her fingertips just a little, tracing the outline of the scar, as if a careful enough touch could somehow smooth it over.

Several moments passed, laden with the unbearable sense of precarious wonder.

‘Forgive my curiosity …’ she whispered, ‘but …’

‘Where did I get this scar?’ Lady Lucy’s voice was lower and softer than ever. ‘You are forgiven. I can tell you, if you want. But you must promise me one thing first.’

‘Anything,’ Hester said before she could even think about the regular, sensible ‘Yes.’

‘Promise me that you will not call me wicked.’

Hester stared at her. ‘I’d never!’

‘Or wild.’

‘Of course!’

‘Or stubborn.’

‘I wouldn’t.’

‘Yes, you would.’ Lady Lucy pressed her finger against Hester’s lips in a gesture of mock sincerity. ‘Consider these words to be under embargo.’

Hester resisted the temptation to lick her lips now, to taste the faint imprint of this exquisite, marble cold.

‘Yes,’ she managed to say.

‘Very well. It was a burn.’

That was clearly a mere preamble. Hester tried not to let her gaze linger on her lady’s fingertips or think of the wintry tenderness of their touch, before prompting: ‘What kind of burn?’

‘A silly one, really. I touched a fireplace grate. Accidentally, of course. I only wanted to retrieve the letters.’

Hester’s head was starting to swim. ‘The letters?’

‘Yes. My cousin’s letters.’

‘Did they end up in the fireplace by accident?’

‘Oh, no,’ Lady Lucy assured her. ‘It was very much deliberate. My mother threw them there. Those letters she could find, that is. But she managed to uncover most of them. The search was quite thorough.’

The meaning of these words didn’t sink in instantly; and when it did, Hester froze.

‘I was careless, of course,’ Lady Lucy continued, her voice now tinted with old scorn. ‘I shouldn’t have left that letter in the library. You see, Blake, I was under a naive impression that my dear mother would never stoop low enough to read other people’s correspondence. After all, wasn’t she raising me to be a paragon of good manners? But, as I’ve found out, she didn’t apply these same rules to herself – at least, when it came to those who couldn’t answer.’

Hester didn’t dare to say anything more, but Lucy needed no encouragement.

‘I’ve never told you about my cousin. What should I say? His name was Albert. He was older, than me – two years older, I think. He studied at Harrow back then, and we can safely say he was very unhappy about it. He hated the cold, hated the discipline, hated the sport. He wasn’t any good at it, either. Weak and pale, just like me; a lover of poetry, just like me.

‘Can you imagine – he tried to teach me Latin by correspondence! I wasn’t tutored in Latin myself, of course. Or in rhetoric. Or in anything much else. He tried to help me with all possible sincerity; he transcribed for me every interesting thing he heard at school.

‘Sometimes he stayed with us over the holidays, and then we used to sit together in the library for hours on end. It was always the same way: he was talking, I was listening, asking questions and writing down everything I could. I was so afraid; you wouldn’t believe it now! I was afraid to forget anything, to lose anything.’

Lady Lucy stopped for a second. Her cheeks were glowing, her breath ragged, her eyes half-closed. Hester caught herself staring, transfixed by this strangely indecent sight.

‘It-it was chaotic, I know it now,’ the young woman continued, evidently trying to speak slower. ‘Everything in one great pile – languages and rhetoric, history and natural sciences. I didn’t think about some system, or about what am I going to do with it. I-I just devoured it all, I think, like some child let into a cupboard with sweets. I was so hungry for sentences, for stories, for information. I never knew before just how hungry I’d been.’ She paused. ‘Perhaps, I am hungry still.’

‘There are worse sorts of hunger in the world.’ Hester smiled slightly with only one corner of her lips.

‘Such as?’

‘Oh.’ She didn’t expect an earnest question. ‘Hunger for wealth, for instance. For fame. For power.’

Hunger for fame. The outlines of one face flared up in her mind, then faded away in the mist.

This isn’t the time.

‘But knowledge is power in its own right, don’t you think so?’ Lucy asked. ‘And power shouldn’t be wielded without good knowledge. Our politicians are the best example of that, I think.’

‘So what happened to your cousin, my lady?’ Hester swerved hurriedly, afraid to let the conversation stray again into that strange, dangerous territory Lady Lucy was oddly attracted to.

‘Ah. My cousin. You’d think, no doubt, that it must have been an awful chore for him – tutoring his little cousin in the dark library instead of spending his holidays in sunshine and games. But, believe me, he enjoyed it. I know it for sure. We’d been exchanging books for years, you know. Well, mostly it was he who sent me anything interesting he got his hands on. Once he even stole a book from the school’s library because he thought I might like it, and I only learnt about it from the news about his detention.

‘He used to say that I was the only one who didn’t laugh at his poems. And how could I laugh? How could anyone laugh? They were wonderful. I used to send him some of my writing as well. He didn’t laugh either. He said it was wonderful. He said I was the only one who understood him.

‘Such bizarre fantasies we used to share! But they were innocent. They were all innocent. Or, at least, we thought them to be innocent enough. We dreamed about getting married as soon as we grew up. We even talked about eloping together! There was no serious planning, of course, but we loved to imagine it from time to time. We pictured enjoying an idyllic life in some secluded cottage, surrounded by meadows. Something about walking hand in hand, exploring secluded groves and bathing in cold blue lakes.

‘He promised to dedicate poetry to me, to write it every waking hour. I promised to weave white flower wreaths for him. They would have looked so nice in his dark hair. I honestly don’t know what I was thinking about. It was as if I had been intoxicated. Perhaps, in a way, I truly had; he was my only friend, you see.

‘My father had always been a little Oriental in his desire to guard my purity – even his acquaintances said so. Male friends were out of the question for me, except the closest of kin. Female friends were … very, very much frowned upon. Sometimes I even think that he must have wanted me for himself.’

Lucy laughed briefly, and Hester thought she had never heard a laughter so brittle and hollow, so entirely devoid of mirth.

‘In other circumstances, Albert would’ve been a sweet companion, nothing more; but as it was, he seemed to be my soul mate, my heavenly twin, my star-crossed lover. I couldn’t imagine living without him. Nor did I want to.’

Lucy stopped to catch her breath, her face flushed and her voice trembling. And, even looking at her with ravenous attention, Hester couldn’t understand, whether it was a tremble of the coming tears or that of a long-buried rage.

‘When my mother read that letter … I would have said there was a scandal, but scandal is too mild a word. I was a little whore, a disgrace, a curse, a monster. I hoped against hope that she wouldn’t find other letters – that this silly parlourmaid wouldn’t confess – that her affection for me as a ‘sweet child’ would be enough to override my father’s authority. I was wrong. I was foolish.’

Hester could see that moment in all its awful vividness. A frightened, enraged child, her face red and wet with weeping. The fire, hot and furious and hungry, devouring the things she held dear. The desperate attempt to salvage one piece before someone’s strong hands dragged her away.

‘I think I kicked someone.’ Lucy’s voice was quiet, but the line of her mouth was set and hard and bitter. ‘And probably bit. I certainly screamed a lot about my hatred. I was overpowered quite easily, of course. Knocked to the ground. My head swam for hours later. I didn’t even realize how it happened – one second I was standing, and the next I was lying on the floor, my head hurting like it would break into pieces. But it forced me to keep quiet, which was just what they wanted.

‘It could have been worse, I suppose. I suppose. They shipped off me to Devon, to live with my aunt for a year. It’s a beautiful place, Devon. And my aunt wasn’t as strict as I feared she would be. But she kept no books, and I wasn’t allowed to take any of mine. Naturally, I harboured some plans of revenge.’ She didn’t change her tone. ‘I even thought about burning the house down – in Gothic novels it always seemed to help. But then, I decided it wouldn’t solve anything in the long term …’

Lucy’s voice trailed off. Her face was now rigid with exhaustion, her eyes gleaming with long-forgotten hatred.

Or not quite forgotten.

Hester felt a lump in her throat. ‘That’s awful.’

There were some more phrases she could use now. However, they ventured very, very far beyond the invisible border of politeness. Too far even for this strange hour in a secluded folly.

Lady Lucy turned away. ‘Thank you, Blake.’ She stared down at her hands, her grip on Hester’s fingers stiff.

Looking out of the corner of her eye, Hester couldn’t help but notice that her lady was blinking unnaturally fast.

‘Forgive me if I’m imposing on you. I am too sensitive …’

‘Not at all!’ Hester hastened to assure her.

However, Lucy continued, her tone monotonous, like a rain-swept plain: ‘Perhaps, it runs in the family. Yes, it must run in the family. My grandmother used to weave bracelets out of the hair of her dead children. Actually …’ She didn’t look up, but something stirred in her voice. ‘It feels tremendously strange, calling you Blake. It sounds a little like a boy’s name, and you look nothing like a boy.’

‘I hope not!’

‘Then, I hope, you wouldn’t object to telling me your Christian name? I promise not to use it in front of anyone. Certainly not my family.’

Of course, Hester thought. By now, Lady Lucy must have adopted a firm policy of not saying absolutely anything in front of her family. Or, at least, anything that could possibly be used against her later.

‘My name is Hester.’

‘Hester.’ Lucy repeated it softly, as if recalling a dream. ‘It sounds like dry leaves in autumn. Were you born in autumn?’

‘No, my lady. I’m afraid my birthday is in May.’

‘Still, it was worth asking. I promise to prepare a good present for you.’ Lady Lucy smiled, her face mellowing for the first time since she’d mentioned Albert’s name. ‘Hester.’

Glancing down, Hester noticed that their hands were still linked; moreover, her finger was still trembling, moving in a futile attempt to smooth over the old scar.

***

You shouldn’t worry about me. Everything is going peachy (crossed out) very well. I even have my own room here, and, believe it or not, a maid comes every morning to light the fire and prepare a bath for me. It feels very strange, almost as if I had a servant of my own. I hope you won’t think I am getting wrong ideas! She is a very sweet girl, in fact; her name’s Abigail. We usually spend Sundays together; we are going out to the nearest town this Sunday, if the weather isn’t too bad.

The house is freezing; the very stones seem to seep with cold. I’m getting used to it, though …

Hester put her pen away for a moment and gazed upon the smooth lines, stretched before her on the white plain of paper. A plain, that seemed endless.

She’d never imagined having to choose her words so carefully while writing to her mother.

Hester remembered the Saturday dances of her hometown, the ones she used to reminisce about with Abby. The giddy evenings, her hair tense in the painstaking (but so elegant!) Marcel wave, the entrance fee clutched in her wet palm. The lively sounds of the foxtrot; for some reason, the band always started with the foxtrot.

There will be a dance tonight, Hester thought dreamily. I wonder, will the orchestra be brave enough to play a tango, or will they stick to waltzes again?

These were exactly the kinds of silly questions she would not dare to put in the letter.

Not now. Not after she’d spent several years all but shouting from the rooftops about her dream to become a proper lady’s maid.

Naturally, becoming a factory girl or a shop girl would have been much easier. But a factory girl or a shop girl spent her life shut in the same little town – one could say, in the same little room. She would never see either great houses or exotic shores, except in magazines.

With a pang of regret, Hester saw that she couldn’t expect straight away to find a job in some magnificent household, serving the lady of the house, who could travel the world as much as it pleased her. It didn’t mean, of course, that Hester didn’t secretly hope for that kind of outcome. But, in the end, reality won: an inexperienced girl with an awkward accent could only hope for a junior post like this.

But this is just a start, she whispered to herself. Just a beginning, and not the worst one, either.

Closing her eyes, Hester could see the course of action she charted for herself like a battle plan. Two, at most three years here; then she could apply for a post as a fully fledged lady’s maid through some well-reputed agency. She would ask for higher wages this time, of course; that was the only way a girl in service could progress, moving from one grand household to the next.

What then? Two years to gain more experience and ensure glowing references; then, perhaps, she could try her luck at one of the great families. The Londonderrys, whom her uncle admired so much. The Grosvenors. The Astors.

What makes you think they’d want you? her inner voice whispered. There’re plenty of unemployed girls who can sew. Now more so than ever.

I am better than any of them! Hester stiffened her grip on the pen.

How so?

Well, I am … I am industrious … I am patient … I am doing everything right!

From the depths of the room, the coloured postcards looked at her with mute expectation.

Hester remembered all these times when, still in her hometown, she used to find some pretext to go to the train station. She lingered there longer than was strictly necessary; she spent time gazing at the passing trains, reading about some possible destinations and imagining others. She felt possessed with longing to jump onto their steps. They would have taken her to the black stones of Edinburgh, to the ancient gates of York, or further South, all the way to the magnificent capital.

No, no, she had absolutely no reasons to complain. In only two months (how could it be March already?) she would be going precisely there. Lady Lucy was, after all, bound to have her second Season, just as she was bound to accompany her.

Hester didn’t doubt that her young mistress would become the belle of every ball. How could she not – with her graceful neck, her ivory skin? Admittedly, Hester was no expert when it came to the ladies of Society; to be precise, she had never met any. But she was sure that none – or, at least, very few of them – could be more beautiful, than her mistress.

But, of course, moving to London also meant another thing. A thing that had nothing to do with Lady Lucy and her romantic prospects.

Almost involuntarily, Hester’s gaze shifted to the lower drawer of her table. Somewhere there, another letter slumbered. It lay quietly in the darkness.

It waited to be answered.