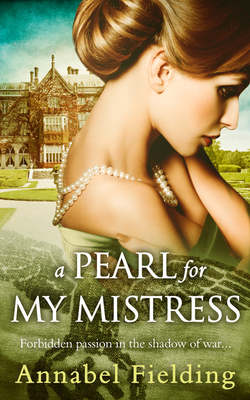

Читать книгу A Pearl for My Mistress - Annabel Fielding - Страница 12

ОглавлениеChapter Five

The pearls slid between her fingers, catching the flare of light. Polished and white to the point of translucency, but slightly uneven, just like real pearls should be.

Lucy never failed to be mesmerized by their beauty, the smoothness, the delicacy. And, of course, by the stories behind them.

They used to embody her dreams of adulthood. She had seen them for the first time (or, to be precise, she was shown them for the first time) that memorable evening years ago. She managed to get the rules right then; to guess and perform everything that was expected of her, to smile at the right moments and say something that would please everyone. For that, she had been rewarded.

You are such a sweet child, they said; you can behave so well, when you only try!

Oh, she tried. Being quiet, decorous, and speaking only when spoken to; Lucy tried her best to remake this burden into a weapon. People conversing around her forgot quickly about a ghostly child lingering nearby. But the ghostly child never forgot; the ghostly child was catching every word. She learnt quickly enough to discern the resentments and desires, and then to avoid the former and cater to the latter. She had to.

You will wear this necklace when you grow older, they said; it’s a family heirloom. You will wear it at your first Season, when you will be presented at Court and stand before Their Majesties. You will have grown into a beautiful young woman by then! And, if you continue behaving well, everything will be splendid. You will have a golden life ahead of you.

She smiled at these predictions, knowing that it would make her cheeks glow with a maidenly blush, and that the adults would find it to be heart-meltingly touching.

The idyll of that evening didn’t last, of course. Soon, the rules of the game changed once more, and again Lucy found herself at a loss, unaware, what might provoke the next scandal. These rules changed quite often, actually. She felt herself like a wanderer lost in the marshes, unsure which path to take, and whether there was a safe path at all.

Several more years passed before Lucy grew exhausted, before she understood that she would never win this game. She was never meant to win it; it wasn’t constructed that way.

The dreams acquired a desperate edge, now mixed with the yearnings for escape. But the pearls – the pearls remained.

Oh, she wore them on her neck later. She wore them during her presentation at Court, when she stood in the queue with the other anxious debutantes.

Lucy looked well enough that night, as she reflected afterwards; but the moment passed, and she curtseyed with her eyes downcast, and Her Majesty nodded, and life went on.

She wore the necklace later, during the stifling debutante balls. She sat on her gilded chair, upright and nervous, her mother standing behind and watching her closely.

The understanding mothers of coming-out ladies always organized such dances jointly. It never came cheap, they said. Have you heard how much hiring a band costs? The flowers? And say nothing of the snacks. To own a great townhouse was now beyond even the dreams of most, let alone the means. Therefore, we will need to come together, to divide the costs, to find a good hotel ballroom …

These are difficult times, darling. Surely we must help each other; how else will our daughters marry?

The heat during these events was suffocating, the etiquette even more so. But the cold, ancient pearls rested somehow reassuringly against her neck.

After all, they held her other dreams, too.

In her adolescence, Lucy used to be mesmerized by the dreams of this elegant future. But, to an even greater extent, she was transfixed by the thoughts of the murky past that the pearls came from. She never asked her mother about their origins directly: partly out of her usual wariness, partly out of fear that the blunt truth might shatter her stories.

And these stories seemed to swirl around her pearls, like moths swirl around a source of light. Maybe – small, fanciful Lucy wondered – her ancestress was a selkie, a sidhe, an elf? Maybe she brought these gleaming pearls as a keepsake from her native land? She abandoned them after falling in love with a mortal – Lucy’s ancestor who was a knight.

Maybe – older, worldlier Lucy pondered – her ancestress was a royal favourite, who received this necklace as a high gift? She took it with her after abandoning the court for the seclusion of Hebden Hall due to some magnificent scandal …

These stories whirled, and tangled, and intertwined with one another. They simply refused to lie still. They buzzed in Lucy’s head, like a swarm of bees. They ignited her blood and pricked her skin, urging her to write them down.

The pearls slid across her palm now, their sublime beauty a sharp contrast with the ugliness of the scar.

… Her mother never shouted. She was, in fact, extremely patient. She often sacrificed hours to sit by Lucy’s side after some lapse, and explain in her gentle, tired voice, how worried she was to have such a daughter. How sad that Lucy would never be received in any good houses. How heartbroken, that she would never inspire love in anyone, that her habits and outlook would earn her so many enemies, so much scorn.

What, Lucy didn’t want to believe it? Oh, of course; she was so young, so foolish. But she had to understand that no one else would tell her these things, because no one else cared about her half as much as her mother did. No one but her mother cared about her at all, in fact. At best, they were just being polite – but she could not believe empty politeness, could she? She was not that foolish, after all.

Her mother was patient, extremely patient. She could go on for hours, hours, hours. Her words filled Lucy’s head, like the thick, stifling fog of the old cities.

At the end of such conversations, Lucy was left stiff and pale as ash, choking back tears. It was so strange; it felt as if she had been beaten black and blue, and yet there was not a single mark on her skin. She felt battered, almost dead, and the fact, that she was still breathing felt somehow unnatural.

She desperately needed something else to fill her head with, some soothing alternative, some safe refuge, something.

And so, she took cover under her stories, as if they were a makeshift tent in a violent storm.

At the end of the day, it was these stories that opened the brilliant new perspectives for her. Perspectives that lay as far from the gilded ballrooms and borrowed fans as they did from the world of gargoyles and draughts.

Lucy could still feel a dreamy smile on her lips when the door creaked behind her. These doors always creaked. On the one hand, it was irritating; on the other hand, though, it provided a sure warning against any unwanted intrusions.

There was no unwanted intrusion this time, though; it was just Hester coming in with a neat stack of clothes. Lucy felt a familiar warmth touching her heart when she saw the girl’s broad features. Hester’s eyes were filled with concentration.

There was a strange pleasure in observing Hester’s precise movements. They were now getting more and more assured, Lucy noticed, as she grew used to her work and her new life. The clumsiness Hester displayed in her first days – sometimes endearing, sometimes as irritating as the creaking doors – was all but gone now.

Lucy was quietly glad. It pained her to see this sweet girl growing rigid with discomfort.

If there was one person in this house whom Lucy wished no ill, it was Hester.

As the maid turned away from the wardrobe now, Lucy could clearly see how her eyes were ringed with red, her face pallid with fatigue.

‘You look quite exhausted,’ she said gently, fighting with the desire to come closer, to stroke the girl’s hair. ‘I hope it isn’t my doing?’

‘Actually, my lady …’ Hester’s white teeth suddenly flashed in a slightly mischievous smile ‘… I am afraid it is.’

‘Indeed?’ Lucy raised her eyebrows. ‘I can only hope you’ll forgive me, then. I certainly never wanted to give you a sleepless night.’

‘Then you shouldn’t have been writing so well.’

‘I apologize, then!’ Lucy couldn’t hold her laugh now. However, her eyes focused on Hester with the utmost earnestness. ‘And, if we speak seriously … did you really like it?’

‘I thought it was marvellous!’ Hester said, agitated. ‘I only wish you would’ve written more.’

***

‘Really?’ Lucy leaned forward eagerly, staring at her maid with unnerving attention. ‘And which part did you like most?’

‘I don’t know. I am not sure … I think I loved all of them.’

‘But if you think of it carefully?’ she persisted. ‘There must be some episodes you liked more than others.’

‘Well …’ Hester struggled. She plucked a hasty answer from the depths of her memory, if only to sate that ravenous demand in Lucy’s eyes. ‘I … I loved that chapter where she outwits the Spanish convoy.’

‘I knew it! That one was incredibly difficult to write, by the way,’ Lady Lucy said with a hint of relish. ‘I think I spent days inventing a way to get the heroine out of that corner.’

Now, when Lucy’s face was ablaze with happiness, Hester felt she could relax.

Almost.

‘I only wanted to ask …’ She hesitated.

‘Yes?’

‘I thought … well, might it be possible that you were inspired … at least partly …’

‘By the story of your ancestors from Granada?’ Lady Lucy asked plainly. ‘I was, yes. Of course I was. Although, to be honest, I’ve been just as inspired by you.’

‘By me?’ The dazed question left her lips before Hester could think of anything cleverer to say.

‘But of course!’ The young lady shrugged her shoulders, as if it was the most mundane observation in the world. ‘You really do look like you’ve come here straight from the streets of old Spain. It’s plain to see for anyone who would care to look. For instance, you have such golden skin …’

Lucy lowered her voice, and Hester was forced to step closer to hear her better.

‘Such enthralling dark eyes,’ she continued, ‘such lovely curls.’

She reached out, touching Hester’s hair, slowly moving one lock away from her brow.

Hester couldn’t see anything remarkable in her hair – sensibly cut short, as always – but she enjoyed the gesture. For the first time in her life, she wished her locks to be more unkempt, with more strands hanging out of place, so that Lady Lucy could repeat it.

‘You are too kind,’ she said quietly. ‘My curls are nothing special.’

‘Oh, but they are,’ Lucy said with transfixing softness, which turned Hester’s thoughts into a molten wax.

She was now touching Hester’s forehead; now her temple, now her cheek. Lucy’s fingertips were smooth to the touch, marble-smooth, marble-cold.

‘Ash-brown. The ashes of Granada. Your hair is the colour of burned cities …’

Hester stood, mesmerized, as the whisper turned into silken threads that bound her. She didn’t dare to move; she scarcely dared to breathe. She was afraid to unwittingly commit some error that would cause the marble-smooth, marble-cold fingers on her face to withdraw.

‘It is only a legend in the end,’ she murmured, too wary to speak louder. ‘The ashes of Granada.’

‘But it is not.’ Lucy shook her head slowly, a dreamy movement under water. ‘I believe it, and so should you. Your forebears did live in that city, the last stronghold of the fallen empire. They saw the legendary warriors marching out of the gates. They conversed with the wisest scholars from all over the Continent. Your ancestors wore silk, and gauze, and the tunics of the Arabs …’

Lucy was now standing precariously close to her; so close that Hester could feel the fleeting warmth of her breath. Then she leaned closer still, and the last words were whispered in Hester’s ear, and their heat almost scorched her.

Unwittingly, Hester leaned to her in turn, eager to be closer still, to feel it again, the warmth and the whisper and the touch.

***

Lady Lucy, however, said no more. She looked at the dark girl with strange, glazed eyes, which gleamed as if with an early fever. They stood in precarious silence, gazing into each other’s faces, each eager to read something in the other, but each unable to interpret it.

‘A Moorish girl,’ Lucy said at last, softly and quietly, never letting her gaze wander from Hester’s eyes. ‘Isn’t that what you are? My Moorish girl?’

‘I suppose I am,’ Hester replied, smiling faintly.

The spell was broken, the silken threads torn apart. Almost unwillingly, Lady Lucy took a step back.

‘I’m glad you liked my writing,’ she said, her voice back to normal. ‘Would you care to read anything else?’

‘Is there anything else?’ Hester asked, breathing slowly as if to calm herself down.

‘Oh, there’re some drafts left. Some are unfinished, I’m afraid.’

Not that many of her drafts had survived to this moment. Lucy remembered rereading some of her early stories, some of her childish attempts at grand novels, and dying of embarrassment. She remembered then feeding them to the golden flame and watching them burn – a pang of sadness in her heart mixed with a dose of relief. Now, at least, they were safely buried, and no one would know about their silliness. About her silliness.

***

‘Will you write anything more about Amina?’

‘The Moorish lady? Well, to be honest, I’m not sure. I’ve more or less finished the story I wanted to write. She survives the Spanish invasion and goes into exile …’

‘But there must be something more,’ Hester persisted. ‘Some later story. She couldn’t have reached the English shores without any adventures at all!’

‘You are right.’ Lucy’s fingers drummed briefly against the vanity table. The same nervous melody. ‘What did we have in England? The Wars of the Roses was definitely over by then …’

‘Maybe she didn’t go straight to England at all! Maybe she stayed in France for several years.’

‘Why would she cross the Channel in the end, then?’

‘I don’t know,’ Hester confessed. ‘I’d just like to read about France.’

‘I know!’ Lucy all but jumped. ‘She was recruited to spy for the French. They needed to know more about the situation as the new dynasty stepped onto the throne. The Tudors, I mean,’ she explained clumsily.

‘But that’s grand! I mean, excellent! And she was an alchemist, wasn’t she? That means, she knew a lot about poisons and … and … other things!’

‘Yes!’ Lucy gripped her hands, her face glowing with excitement. ‘Yes, that would be splendid! But she would have to cross to our side in the end. By the end of the second book, at least.’

‘She can meet a lad, some fine young Welsh archer. He will have blue eyes …’ Hester said somewhat wistfully.

Lady Lucy waved the suggestion aside.

‘No, defecting for love won’t do. I mean, there are thousand stories like that written already, and almost none of them managed to convince me. I am not saying that such foolish women don’t exist, of course. It’s just that I am still yet to meet any. No, we’ll invent something more interesting. Something much, much more interesting …’

Again, that drumming. Again, that unnerving rhythm.

‘Oh, this is going to be champion. I mean, splendid,’ Hester breathed. ‘It will be so much better than all those spy stories about sinister Germans.’

‘Are they still around? I’ve noticed they’ve started to go out of fashion lately. Perhaps people are finally realizing that the war is over.’

‘Well, that’s the North for you,’ Hester joked. ‘We are slow to follow fashions. Some of our girls in the tailor’s workshop were still wearing Eton crops.’

‘Oh, speaking about the North – you should teach me this peculiar dialect of yours one day. It sounds very crisp.’

‘I would! But I’m afraid Her Ladyship will flay me alive for corrupting her daughter.’

‘Corrupting me!’ Lucy laughed. ‘No, Hester. I don’t think you will manage to corrupt me.’

‘Her Ladyship might think otherwise.’

‘My mother –’ Lady Lucy emphasized these words ‘– doesn’t need to know things that can distress her. I wouldn’t be a good daughter if I were to endanger her fragile nerves, would I? Unfortunately, my lady mother happens to be distressed by practically everything; therefore, I have to prevent all these things from reaching her delicate ears.’ She smiled a delightful, open smile. ‘I am a good daughter, after all.’

Hester didn’t find words to argue with that. Not that she tried particularly hard.

That afternoon, she left the room with a great stack of pages. Some of them were covered with a neat type, some with florid handwriting; some seemed to be almost fit for publishing, some were patched with ink stains and irritated cross-outs.

All of them promised sleepless nights.

Hester’s head was still slightly swimming from the exhaustion of the morning, but her hands were trembling with excitement. The future was great, splendid, champion, golden. It held irresistible new books she could be the first in the whole world to read. It held a service to … no, a company of her lady. It held the trip to the capital she had dreamt about since her childhood years.

She couldn’t imagine anything that could throw her from the Olympus of her happiness today.

***

The house was growing dark and sleepy. It was as if some complex mechanism was gradually coming to a halt, its intricate cogs slowing down.

The old silver downstairs was getting locked up. The kitchen maid was finishing the last of her chores, polishing the old pans with salt and lemon skins, so that tomorrow they would shine like burnished gold. The Countess’s own maid was brushing her mistress’s hair for the required fifty minutes, so they, too, would always shine like burnished gold.

Hester Blake tiptoed into the dimly lit library, a heavy tome under her arm. She had to return this anthology of adventure stories today; it wouldn’t do to keep other people’s books in her room for longer than was necessary. And, in any case, she now had plenty to read.

She would not start today. She had to sleep sometimes. But tomorrow evening … or, even better, Sunday. A whole day, spent away from the damp cold of the early spring, in the company of engrossing new stories that no one had ever read before her.

I’ll have to tell Abby I won’t be able to come with her this weekend.

But then, Abby would surely understand. She’d do just fine without her.

Hester carefully placed the old book in its usual place and threw an accustomed glance at her lady’s working table. The typewriter stood there silently, all the papers taken away. Hester couldn’t help but sigh: she wished Lady Lucy was just as careful and tidy with everything as she was with her clandestine writing. The magazines and newspapers were spread over the table rather chaotically.

Poor Abby, Hester thought. She must’ve been really tired today to forget to clean it up.

Yes, she remembered; there was a reason for that. The laundry had finally come back today, and it was up to Abby to check the state of the sheets.

These napkins, pillowcases, sheets, tablecloths, and towels – everything, that needed to be mended, patched, darned, and given a respectable appearance; it seemed to cover Abby’s life, like masses of snow.

Hester couldn’t now even breathe the velvety scent of beeswax, rising from the polished floors, without thinking of Abigail’s calloused hands.

She closed and folded the newspapers, arranging them into a neat stack. She couldn’t help but admire Lady Lucy’s diligence: here were, as far as Hester could recognize, most of the publications she either wrote for regularly or contributed to occasionally. Apparently, she tried to keep an eye on all the latest developments in the world beyond these walls.

The next title, unearthed by Hester’s efforts, made her stop and stare in a vague not-quite-recognition. The front page was adorned by a great symbol: a striking lightning bolt in a black circle. Beneath it was a similarly familiar, starkly printed name: The Blackshirt.

Hester strained her memory. Where could she have seen it? Definitely not here. Still in her hometown, perhaps? Did anyone she knew read it? Anyone in her family? No, she would’ve …

And then, it clicked.

Yes, of course.

An autumn evening, an eerie glow of gaslights on Northumberland Street. And a chant, sudden like a wind, cutting her ears like a knife.

‘Two-Four-Six-Eight-Whom-Do-We-Appreciate: Mosley! Mosley! Take a leaflet, Miss.’

She took it partly out of politeness, out of a perpetual desire not to offend; partly because she was too startled to argue. She didn’t remember the text on the leaflet now, but she remembered the word. The Blackshirt. No, in plural: the Blackshirts.

Yes, she’d heard that word, she’d heard it all right. It didn’t come up regularly in any discussions; however, it still managed to reach her every now and then, touching her ears like a draught of wind.

Hester remembered the brooding young men, gathering for the meetings outside the pub. She saw them sometimes, if she passed by on a Friday evening. She thought of the hunger in their eyes, of the gloom in their faces.

And her Lady Lucy was curious, after all. She wasn’t content with dedicating her attention to – how did she put it? – christening receptions and the length of women’s skirts. She knew about the Hunger Marches, about the Northern troubles. Moreover, she seemed to be able to recall every single instance when the protesters were spotted singing Red Flag.

There is nothing to be surprised about, then. Nothing to worry about.

That was what Hester was telling herself, when her glance fell on the tiny printed words beneath the grand title.

Editor: A. K. Chesterton.

I know this name.

Of course, her inner voice reasoned. It’s just like the writer. The mysteries you used to borrow all the time, remember?

No, no, that was something else.

She must have heard it …

Yes.

She remembered the moment now; it was tinted with her own curiosity and marvel at the power of the machine.

Could it be a coincidence?

What do you think? The inner voice again, impatient. How many editors called Chesterton are there in this country?

Probably not many, Hester conceded.

I absolutely had to find these numbers.

What kind of numbers could Lady Lucy have needed for her usual articles? The number of guests at a costume party …?

Everything will change soon, Blake.

And those responsible for it will answer.

It was no empty consolation, then. It was a sincere promise.

Suddenly, Hester felt very cold.

So, her lady wasn’t merely a curious observer. She was one of the acolytes.

Why do you think it so strange? You know next to nothing about the Blackshirts. Lady Lucy is a reasonable person; surely she wouldn’t have supported them without good reasons?

Perhaps their aims were noble, even if they looked a little disconcerting. Perhaps.

And still, Hester couldn’t get rid of a tight, unpleasant feeling forming in her chest.

Apprehension. Resentment. Bitterness.

She didn’t even tell me! The bitterness in her wept, unpleasant and irrational and strong. She didn’t even tell me.

Why should she have? her mind asked in return. You are her maid.

***

Lucy Fitzmartin lay in the darkness, feeling absolutely no inclination to sleep. Her mind was ablaze with stories, with thoughts, with possibilities. She could feel the spectres of a thousand plots at her fingertips. Words flared up in her head, colliding and intertwining with one another, forming sentences and paragraphs of the stories yet to be written.

Now she had someone to read them.

What was it about Hester that made her open up like a flower, vulnerable as an overexcited child? She would have never showed these scribbles to any of the Bright Young Things she met last year – not even to Nora Palmer, sweet though she was.

Guarding her words like a poisonous medicine, remembering every favour and dissecting every gesture; it all felt as natural to Lucy as a corset must have felt to her grandmother. With Hester, that was different. Why? Was it because she was safe? A servant girl, a half-invisible creature? No, hardly. Lucy knew better than most just how painfully these seemingly harmless creatures could stab you.

Something else, then. What? Her gentleness? The spirited ring in her voice when she defended these – what was it? – landscapes of Northern counties?

Lucy found herself smiling, absent-mindedly and happily.

Well, even her grandmother must have taken her corset off sometimes.

In less than two months, they would finally be away for the Season. Lucy couldn’t wait to show her new confidante all the wonders of the ancient capital. She was also impatient to return there herself, to find herself once again at the magnificent heart of the Empire – a dying, withering Empire, but an Empire nonetheless. At the place where everything important happened. At the place where all the vital decisions were made.

She would meet, once again, her comrades-in-arms. She would shake Mr Chesterton’s hand. She would hear Sir Oswald speaking.

Her introduction to the movement was almost as accidental as her introduction to the Society journalism. Lucy fulfilled the promise, given to herself that sunny afternoon in the restaurant of Claridge’s hotel. She set out to find out everything she could about Oswald Mosley and his supporters.

Initially, she was prepared for something laughable – something like Sanderson’s English Mistery that proposed to re-institute feudalism in Britain and condemned pasteurised milk as a cause of physical degeneracy. She was prepared to join in the hearty ridicule, to participate, at last, in her companions’ witty banter about these thugs.

Lucy was glad to have an aim, even such a petty aim. She gulped down all the information she could find as hungrily as she used to gulp down old novels or her cousin’s textbooks. Newspapers and pamphlets, brochures and weighty political tomes.

Yes, it felt good to have an aim.

But the things she found out didn’t make her laugh. In fact, they didn’t even make her smile. To be extremely precise, they made her freeze in horror.

Sir Oswald’s aims were very, very far from laughable. And the more she learnt about the problems he proposed to combat – in other words, the more she learnt about how things really were – disbelief and horror slowly turned into anger.

She could guess, of course, that the country wasn’t exactly in its halcyon age. Even in the careful isolation of the debutantes’ society, she caught some offhand remarks, some weary sighs about the inept government officials, some distant fears of a Communist invasion. Nothing you should concern your pretty head with, darling. Better think about the upcoming dinner at the Astors’.

Surely nothing to be concerned about. It was just her country crumbling around her. Nothing to worry her pretty head about. Better to sit in her doll’s house and write about other doll’s houses, before the hurricane comes and tears them all to shreds.

She learnt more and more, eagerness mixing with fear, about the closed shipyards and silent factories. She learnt about the towns, counties, regions quietly going mad with desperation. She learnt about the ‘children of the Empire,’ given up by starving families and sent to the colonial farms as cheap labour.

These tragedies didn’t play out in some far-flung land; they were only a couple of steps, perhaps a short trip away. And yet, here she was, insulated in petty Society dramas.

And the government officials, it seemed, were just as unwilling to touch these problems as any debutante on a golden chair would be.

Of course, she wasn’t supposed to think about such things, much less bring them into a discussion. For a lady to mention such an interest in a conversation with an eligible young man was a disaster in the eyes of any mother.

Today’s gentlemen are quite superficial and airheaded, they said; one could even go so far as to say they tend to be quite brainless. We cannot change that. Therefore, you will have to make every effort to hide any intelligence you possess. Imagine how the poor boys might be scared otherwise! And you don’t want to scare them off, do you? Talk about weather, ghosts, and the royal family. One cannot go wrong with these topics.

She couldn’t share her fears and thoughts with anyone of her acquaintance; she couldn’t let out the words, screaming in her mind.

Fine.

If they won’t listen to me, then I’ll find someone, who will.

It was with these thoughts she slipped away one fine afternoon, plainly dressed, to hear Sir Oswald speak.

She had heard many outrageous things about Oswald Mosley. He was a philanderer who broke his poor wife’s heart and finally drove her into an early grave. He made her younger sister Alexandra his mistress even before that.

Of course, the innocent young debutantes weren’t supposed to hear such gossip. However, as no one cared enough to seal their ears with wax, they still did. Lucy certainly did: she was well trained, after all, to keep quiet unless spoken to and listen to what others had to say. And others had a lot to say, especially if prompted gently in the right direction.

Thus, she heard the heart-wrenching story of Cynthia Mosley, née Curzon, and she despised Mosley the man.

However, at the same time she couldn’t now help but admire Mosley the leader.

It was as if they were two different spirits trapped in the same body, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde of the new century. As Mosley rose to the tribune and addressed the crowd, Lucy didn’t see a sleazy adulterer, a patron of the resorts of the French Riviera and a tireless seducer of married ladies. Before her stood an ardent genius, a visionary leader, whose words were as clear and merciless as an Oriental blade.

She had heard that Mosley never resorted to radio broadcasts, that he even disliked using a microphone. Now she saw why. No radio waves could have ever conveyed such a fiery presence.

She also saw why he had initially called his movement the New Party. It was new; it was different. He was different. Who had ever heard before of a peer resigning from a brilliant career in Parliament to lead a street movement? For many, that was a reason to sneer at him in their drawing rooms.

He is strange. He is mad. He is not like the other, normal politicians.

And it was true – he was not. Lucy saw it now, as clearly as the light of the day. He was a fire to their marsh, a strike to their meddling, a thunderbolt to their drizzle. A thunderbolt now adorned the banners of his new movement, and the movement itself acquired a new name: the British Union of Fascists.

Having arrived at the rally with a mixture of apprehension and curiosity, Lucy now clung to his every word with ravenous hunger. Every word filled her heart with thrill and her head with new clarity.

Suddenly, everything she had ever heard, or read, or felt or wondered about started to make sense. These vague, disconnected patches of knowledge, rumours, and suspicions were now coming together, intertwining to form a whole picture. She saw the full extent of the danger looming over her country; she also saw the way to save it from this danger. And, above all, she saw the man who could do it.

When, after his speech ended, the burly young men around her shouted in enthusiastic agreement, she shouted too. She must have looked quite comical – a dainty, small lady in white gloves, jumping and flushing and screaming. But she couldn’t help herself – the wave of fire engulfed her, and the fire seeped into her veins. It prodded, propelled her, driving and begging her to do something, to run, to fight, to help the cause.

At present, the only place she could run to was to the respective stall, to sign up for the membership and receive her badge. She had to hide that one, too, as she took care to smooth her appearance over and hurry back home.

But the thoughts didn’t leave her, and neither did the fire.

She had never felt so alive before. She was afraid to lose that feeling, to slip into the apathy and frustration once again; but her fears proved to be unfounded. Soon, she started to fill her diary with furious drafts and excepts from yet-unwritten articles: ‘What do we keep our government for? To organize elaborate processions? What is the purpose of the government, if it stays deaf to the needs of the people it supposedly serves?’

She tossed and turned at night, thinking of how, precisely, she could help the cause. She looked enviously at the glowing newspaper photos of tough Blackshirt girls practising jiu-jitsu. But she couldn’t join them, of course – literal fights were out of the question.

Nominally, she was now a part of the Women’s Section, headed by the motherly Lady Maud Mosley (who was, quite literally, the leader’s mother). Really, Lucy rarely had either time or opportunity to attend their meetings.

Several sleepless nights later, she had worked out a way she could be useful to the new movement. Frankly anyone could distribute leaflets on the street; however, not many could write them.

If her skills looked sufficient for the proprietor of national newspapers, then, perhaps, they would prove somewhat useful for the leaders of a fledgling movement?

At first, Lucy was too anxious to approach Mr Chesterton, the newly appointed editor of The Blackshirt. She had actually feared that her own modest title might create some difficulties, or even bar her from active participation altogether. After all, wasn’t she the very part of the enfeebled old world the new movement vowed to sweep aside?

But her fears proved to be unfounded. Moreover, Lucy discovered that she had drastically miscalculated the situation. Yes, dashing Sir Oswald professed to despise the ‘old guard’ of traditional parties and the cautiousness of landed gentry. However, at the same time he desperately wanted to cultivate some allies among these very groups: the allies, who could lend a measure of legitimacy to his controversial Union.

Not only did Mr Chesterton accept Lucy’s overtures – he welcomed her with open arms. He welcomed her, in fact, even before Lucy managed to show him some of her clumsy drafts.

Once again, her title proved to be an unexpected asset; once again, the arsenal of illusions gave her a weapon. Naturally, this time it was not the flair of elegance, but the might of tradition. It promised to give clout and respectability to the rough young movement.

It was a lesson for her to remember: not even the most daring, inspiring leader could ignore the realities of power. And who said that illusions have no power? They certainly hold significant power over people’s minds, whether those people read The Blackshirt, The Times, or Tatler. And isn’t the power over people’s minds the ultimate power, in the end – the one from which all the other kinds of power stem?

The more she pondered it, the more reasonable it looked. After all, people don’t usually tend to respond enthusiastically to the prospect of being swept aside.

Lucy moderated the tone of her own articles accordingly: fewer exclamation marks and radical statements; more gentle suggestions and solid numbers. The dissatisfied youths from the destitute industrial towns, who joined the BUF by thousands, could be responsive enough to the flaming rhetoric. But smart people, educated people, people holding important posts – in short, people who mattered – would demand a sound proof of each claim.

Well, then Lucy wasn’t going to disappoint them.

Fewer exclamation marks. More gentle suggestions.

I am certainly far from saying, that the current Party system is intrinsically vile and ineffective, she wrote. However, it was designed by and for another century. It worked well enough during the days of Queen Victoria; under its reasonable guidance Britain became the greatest empire in the world. But, as much as we laud the successes of the past, we must look to the future.

A decade ago, we declined to follow other countries’ examples and invest in the research on diesel; we clung stubbornly to our steam technology, the technology that made us so prosperous during the last century. This failure has cost us millions. Now, in a similar vein, we stubbornly refuse to be inspired by the examples of strong leadership, unhindered by the bulky Party machine, which we can see on the Continent …

The North, where she had to spend her winter and spring, certainly provided her with enough research materials as well as inspiration, however horrid. But, deep down, she always longed to return to the capital. That was where everything happened; that was where she could feel the pulse of life.

Besides, this year everything would be different. She was no longer a clumsy debutante, knowing nothing and no one, meeting only at closely supervised receptions with the fellow clumsy debutantes. Now, she had some connections, and an income, and a degree of freedom, and prospects, and a cause …

And, last but not least, she had her Hester.

Lucy smiled softly, thinking of her maid’s (her friend’s!) dark, perceptive eyes. No doubt she would be delighted to see London.

Yes, she thought, drifting at last to sleep. This is definitely going to be an interesting Season.

***

County of Northumberland, May 1929

The crowd outside the cinema was enormous. Even Hester, whom everyone considered to be too tall for her fourteen years, had to stand on her tiptoes to see the end of it. The ‘children’s afternoon’ on Saturdays always attracted hundreds of hungry viewers, but today they looked like an army ready to charge.

Hester resented the name of the programme; she was not a child, after all. She cheered the special prices, though. One penny for the stalls – that was something! The balcony was still off limits, though.

She would always sit in the balcony, once she got a job of her own; Hester promised that to herself.

‘Thanks for holding my spot!’ Susan stood before her now, her cheeks flushed, her breathing heavy. Had she run here all the way from that corner shop?

‘I thought they’d stamp me to death! No need to run, actually. They won’t open the door for five more minutes at least.’

‘Oh well. Didn’t want to be late.’ Susan was still trying to slow her breath down, her fair hair glinting with sweat. ‘If I was, I’d never find you here. It’s madness, isn’t it?’

‘I know!’

The cinema bore the majestic name of Embassy. It was built to resemble an Egyptian temple, a grand structure of black and gold. The craze for Egyptian mysteries, prompted by the discovery of that tomb a couple of years ago, was dying down now; but the cinema remained as alluring as ever.

Every afternoon crowds gathered outside the entrance, and Hester never failed to be annoyed with these people, despite being one of them. She stretched her neck impatiently now, awaiting the signal that the doors were open. Her heartbeat measured out the seconds.

‘Have you got it?’ she asked Susan, turning to her again.

‘They had no more Mint Imperials.’

‘Oh!’

‘I bought some Fry’s instead. Is it okay?’

‘Yes! I love chocolate. I’ll give you the halfpenny back after the movie. Will it do?’

‘Ab-so-lu-te-ly!’

When Susan spoke, she often tried to emulate the glamorous gangster sweethearts she’d seen on screen. Hester found it adorable, and honestly tried not to laugh.

They both loved ‘talkies,’ even though some of their friends derided the silly accents now uncovered.

‘I hope they won’t screen the old movies today,’ Susan breathed.

‘Me too! They showed that one with Lillian Gish last Saturday.’

‘Oh, but I love Gish! Isn’t she a doll?’

‘I know! Did they say how long this one would last?’

‘Nae. Why do you ask?’

‘I’ve got to be home by evening. I’ve a lot to do. I still have to blacken Da’s boots for Sunday, and …’

‘Oh, Hettie! You should relax for once. Naebody will die there without you. And won’t Sophie help you?’

‘Sophie isn’t here any more,’ Hester reminded her.

‘Oh, damn. I always forget. It’s so strange, isn’t it? The thing she’s done. It’s … well, it’s really like in the movies! It usually ends badly in the movies, but still.’

‘Well, thanks for cheering me up; I wasn’t worrying enough myself.’

‘You can always count on me!’ Susan giggled.

Hester almost stumbled as the crowd to both sides of her started to move. Her own feet carried her forward, caught up in the momentum. She clutched Susan’s hand, slippery with the sweat of excitement. Soon, they would enter the palace of dreams, where she wouldn’t need to think of boots to blacken, or stockings to mend, or breakfasts to cook.

When the last of the young spectators had crossed the threshold, the door shut behind them with a deafening thud.