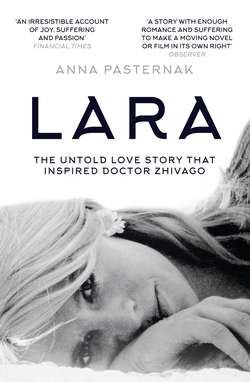

Читать книгу Lara: The Untold Love Story That Inspired Doctor Zhivago - Anna Pasternak - Страница 12

3 The Cloud Dweller

ОглавлениеIt was at a party in Moscow in 1921 that the thirty-one-year-old Boris met the painter Evgenia Vladimirovna Lure. Petite and elegant, with blue eyes and soft brown hair, Evgenia came from a traditional Jewish intellectual family from Petrograd. She spoke French fluently and had a cultural finesse which Boris was drawn to. His attraction no doubt bolstered by the fact that Leonid knew Evgenia’s family and heartily approved of the union. Boris, who always sought his father’s approval, duly fell in love with her.

‘One wanted to bathe in her face,’ he said, but also pointed out that ‘she always needed this illumination in order to be beautiful, she had to have happiness in order to be liked’. An insecure and vulnerable beauty, she was flattered by the famous writer’s interest in her. By the spring of 1922, they were married. ‘Zhenya’ was twenty-one years old.

If relationships act as mirrors to our flaws and our needs, Boris learned much about himself during his first marriage. Evgenia also had a volatile, artistic streak and their clash of egos was not conducive to marital harmony. Boris’s fame was impacting his ego; he did not consider Evgenia enough of an artist to merit her difficult, emotional behaviour. Of the two of them, he considered himself the greater artist and assumed Evgenia would lay aside her ambition to help foster his, just as he had witnessed his mother do for his father. While he was by nature active, preferring to run everywhere rather than walk – probably to help burn off his excess nervous energy – Evgenia was languid, preferring to sit around the house. Energetically, they did not seem compatible.

Boris travelled with his new wife to Berlin for a holiday in the summer of 1922. It was Evgenia’s first time abroad and the newlyweds relished their time in the German capital, visiting bustling cafes and art galleries. While Evgenia liked to sightsee and enjoy the pulsating life of fashionable quarters, Boris, like Tolstoy, was more drawn to the ‘real Germany’: the misery of slums in the northern districts of the city.

Boris was paid in dollars for some of his translation work. He spent his money freely. Ashamed of having so much relative to the poverty of so many, his tips, like his brother-in-law Frederick’s, were always blushingly generous. According to Josephine, who sometimes accompanied her brother on his walks around Berlin, he also ‘showered hard cash upon pale urchins with outstretched hands’. Boris explained his and Tolstoy’s attraction to the less privileged: ‘people of an artistic nature will be attracted by the poor, by those with a difficult, modest lot in life. There everything is warmer and riper, and there is more soul and colour there than anywhere else.’

Once the first cloudless weeks of gallery visiting and seeing old friends were over, the writer began to get restless, and irritable. Evgenia suffered from gingivitis, an inflammation of the gums, which caused her to cry a lot. But Boris was indifferent to her suffering. ‘We, the family, sided with her,’ explained Josephine, ‘but what could we do? Boris did not display any kind of callousness: he simply seemed fed up with the incongruity of the whole set-up – the boarding house, the lack of privacy, his wife’s uncontrollable tearful moods.’ The family raised eyebrows further when he decided to take a room of his own where he could work in peace. This they considered sheer extravagance. The last straw came when Evgenia discovered that she was pregnant. The quarrels became fiercer: ‘A child! Slavery! It is your concern, after all,’ Boris would say to his wife, ‘you are the mother.’

‘What?’ Zhenya would cry out, ‘mine? Mine? Oh! You, you – you forget that I am devoted to my art, you selfish creature!’

The main source of their tension was whether and when they should return to Moscow. Boris was keen to get back to Russia, while Evgenia preferred Berlin, ‘Russia’s second capital’. The vitality of Russian intellectual life reached its zenith in the early 1920s, then declined under the impact of widespread political unrest and soaring inflation. The bleakness of Germany’s fate saddened Pasternak, who later wrote: ‘Germany was cold and starving, deceived about nothing and deceiving no one, her hand stretched out to the age like a beggar (a gesture not her own at all) and the entire country on crutches.’ Typically theatrical, he added that it took him ‘a daily bottle of brandy and Charles Dickens to forget it’.

Back in Moscow the couple moved into the Pasternaks’ old apartment on Volkhonka Street. Soon after returning, on 23 September 1923, their son, Evgeny Borisovich Pasternak, was born. ‘He is so tiny – how could we give him a new, an unfamiliar name?’ Boris wrote. ‘So we chose what was closest to him: the name of his mother – Zhenya.’

Uncertain of his income, and unable to make ends meet with the advances from publishers for his own work and translations, Pasternak worked for a short time as a researcher for the Library of the People’s Commissariat for Education in Moscow. Here he was responsible for reading through foreign papers and censoring – cutting out – all references to Lenin. He turned this mundane exercise to his advantage: scouring the foreign press enabled him to keep abreast of Western European literature. During intervals he read, amongst others, Proust, Conrad and Hemingway. He also joined the Left Front of Arts, whose journal, LEF, was edited by the poet and actor Vladimir Mayakovski, who had been two years below Boris at school. When Boris became part of the front it was more as a gesture of solidarity to his old associate than a genuine desire to become actively involved in the group and its revolutionary agenda, and he broke with them in 1928. That same year he sent the first part of his autobiographical prose offering Safe Conduct to a literary journal for publication.

In April 1930 Mayakovski suffered a mental breakdown, penned a suicide note and killed himself. His funeral, attended by around 150,000 people, was the third-largest event of public mourning in Soviet history, surpassed only by those of Lenin and Stalin. In 1936, Stalin proclaimed that he ‘was and remains the best and most talented poet of the Soviet epoch’. Olga later wrote of Mayakovski: ‘In many ways the antidote of Pasternak, he combined powerful poetic gifts with a romantic anguish which could find relief only in total service to the Revolution – at the cost of suppressing in himself the urgent personal emotions evident in his pre-revolutionary work’.

Increasingly frustrated that he did not have the freedom to write what his heart desired, Pasternak found his daily life almost intolerable. Working conditions – always of utmost importance to Boris – had become unbearable. The entire Volkhonka Street block had been requisitioned by the state and turned into one communal apartment housing six families: a total of twenty people, sharing one bathroom and kitchen. Boris and his family were granted permission to use his father’s old art studio as their living space. It was incredibly noisy, so Pasternak moved his work to the area which served as a dining room. Hardly conducive to concentration: it was open house to the other families, their visitors and relatives. Pasternak was at this time working on an intricate translation into Russian of Rainer Maria Rilke’s haunting ‘Requiem for a Lady Friend’, which the writer had penned as a tribute to his friend the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, who suddenly died eighteen days after giving birth to her first child.

By 1930 Pasternak had become infatuated again – this time with Zinaida Neigaus. What is extraordinary is that for a man with such a fierce sense of morality, Pasternak failed to honour one of the most basic codes of life – he ran off with the wife of one of his best friends.

He admired the esteemed pianist Genrikh Neigaus almost to the point of obsession. In a letter to his mother on 6 March 1930 he had written: ‘The only bright spot in our existence is the very varied performances by my latest friend (for the past year), Heinrich Neuhaus [Genrikh Neigaus]. We – a few of his friends – have got into the habit of spending the rest of the night after a concert at one another’s homes. There’s abundant drink, with very modest snacks which for technical reasons are almost impossible to get hold of.’

Boris was quickly enthralled by Zinaida. The daughter of a St Petersburg factory owner, from a Russian Orthodox family, with her black hair cut short and well-defined lips, she was a classic ‘art nouveau’ figure. She was also everything Evgenia was not. While Evgenia was highly emotional and yearned for the fulfilment of her own creative life, Zinaida Neigaus was happy to facilitate her husband’s career. When Genrikh gave winter concerts in cold halls, Zinaida would organise the arrival of the grand piano and lug the firewood in herself to stoke the fire. While her husband remained with his head in the artistic clouds – he was proud of telling friends that his practical skills were limited to fastening a safety pin – Zinaida raised their two sons, Adrian and Stanislav. She was endlessly energetic, robust, domestic and practical, unlike the elegant but languid Evgenia. Boris’s nephew Charles, who met both women, remembered: ‘Despite Boris’s ardent description of Zinaida, I found her (admittedly more than twenty-five years later in 1961) one of the ugliest women I have ever met. Evgenia was softer, more sensitive and far more attractive than the harsh, raven-haired, chain-smoking Zinaida.’

Pasternak’s interest in Zinaida grew during the summer of 1930 when he and Evgenia holidayed in Irpen near their friends, the historian Valentin Asmus, and his wife, Irina. Zinaida, Genrikh and their sons, then aged two and three, made up the party, along with Boris’s brother Alexander (called Shura by the family), his wife Irina and their son Fedia. Irpen was beautiful: languorous heat, oxen grazing in the fields, meadows filled with wild flowers and in the far distance, the shaded banks of the River Irpen: summer at its fullest and finest. Boris and Evgenia’s dacha stood in its own grounds surrounded by woods. Evgenia spent part of the summer painting an oil of a gigantic spreading oak tree which filled their plot of land. Long evenings were spent eating outside, watching fireflies and candles flicker in the dusk, discussing philosophy or literature, reciting poetry and listening to Genrikh play.

Zinaida had arranged for a grand piano to be delivered from Kiev so that her husband could practise for a recital that he was giving on the open-air stage of Kiev’s Kupechesky Gardens on 15 August. The whole group from Irpen attended the concert. As the humid night progressed, thunderclouds gathered. Genrikh played the Chopin Concerto in E minor to great acclaim. By the end of the performance, a violent storm had broken out, with flashing lightening and thunderous noise. While the pianist and orchestra were sheltered under a platform canopy, the audience became drenched. Yet they all remained, happily entranced by the music. This evening and Genrikh’s playing of Chopin’s E-minor Concerto formed the subject of Pasternak’s poem ‘Ballade’, which he dedicated to Genrikh.

While the summer proved to be the perfect tonic for Boris, Zinaida and Evgenia had taken against each other – perhaps intuitive to the fact that they were soon to become rivals. Initially, Zinaida tried to avoid the Pasternaks. She was not only alarmed by Boris’s excessive praise of her domestic prowess – he would take any chance to help or gather firewood, bring in water from the well or hang around her to sniff her freshly scented ironing – but because she disliked Evgenia. Zinaida, rigorous to the point of military standards in her domesticity, found the elegant, ethereal Evgenia spoilt, lethargic and indulgent. Meanwhile Evgenia dismissed the stocky Italianate-looking woman as unsophisticated and coarse. Boris blithely ignored the mounting tensions between them.

The group broke up in September and by the end of the month, only Boris and Zinaida’s families were left. They were all due to leave early next morning. The night before, Zinaida, having already packed, went to Boris’s dacha to see if they were ready. She found Evgenia assembling the canvases that she had painted all summer, while Boris was busy putting things in suitcases with the painstaking care he had learned as a child. As there was little time left, Zinaida swept in and efficiently finished all their packing. Boris was lost in admiration. Zinaida, with her proprietorial and bossy nature, must, however, have been wholly unwelcome to poor Evgenia. Later, Boris expressed his veneration for Zinaida in the opening lines of the first poem in the collection Second Birth.

Would I have found the strength to act,

without the dream I dreamed in Irpen?

Which showed me what largesse a life could hold,

the night we packed our things to go.

The following evening the two families boarded the Moscow-bound train from Kiev. Genrikh and his two sons were asleep when Zinaida stepped out into the corridor to smoke. Boris left Evgenia and their son sleeping too, to follow Zinaida. For three hours they stood in the corridor talking as the train rattled on. Boris, who could contain himself no longer, confessed his love for Zinaida.

In an almost comical attempt to dampen his ardour, Zinaida recounted an episode from her childhood. She told Boris that from the age of fifteen she had been the mistress of her cousin, Nicolai Melitinsky, who was then forty-five. Her father, a military engineer, who had married her eighteen-year-old half-Italian mother when he was fifty, had died when Zinaida was ten. Finances had been tight for her mother, who scraped to send her to the Smolny Institute for girls. Meanwhile she and her middle-aged cousin met for trysts in a flat rented for that purpose. The guilt of these years was later to torment and appal her.

Naively, she had not bargained for the fact that the burgeoning novelist in Pasternak would be more engaged by her tale of humiliation than dispirited or disgusted. Shortly afterwards, Boris described her as a ‘beauty of the Mary Queen of Scots type, judging by her fate’. Zinaida’s teenage affair was to become Lara’s ‘backstory’ in Doctor Zhivago: she is seduced by the much older lawyer Victor Ippolitovich Komarovsky: ‘Her hands astonished him like a sublime idea. Her shadow on the wall of the hotel room had seemed to him the outline of innocence. Her vest was stretched over her breast, as firmly and simply as linen on an embroidery frame … Her dark hair was scattered and its beauty stung his eyes like smoke and ate into his heart.’ When Lara talks of how damaged she is by her affair with Komarovksy, you can almost hear Zinaida on the train trying to discourage Boris. ‘There is something broken in me, there is something broken in my whole life,’ Lara says to Yury Zhivago. ‘I discovered life much too early, I was made to discover it, and I was made to see it from the very worst side – a cheap, distorted version of it – through the eyes of an elderly roué. One of those useless, self-satisfied egoists of the old days who took advantage of everything and allowed themselves whatever they fancied.’

The seeds for Lara’s character were sown by his meeting Zinaida, but when Boris later fell for Olga Ivinskaya, it was she who fully embodied as a living archetype his Lara.

Soon after his return from Irpen, Boris caused mayhem. Selfishly putting his own desires first, he confessed his love for Zinaida to Evgenia, then went to Genrikh and declared his devotion to the pianist’s wife. In typical Boris style, the meeting was emotional and highly charged, with both men weeping. Boris spoke of his deep admiration and affection for Genrikh, and in an act of gauche insensitivity presented him with a copy of ‘Ballade’. He then insisted that he was incapable of spending his life without Zinaida.

Boris’s confidante, the poet Marina Tsvetaeva, thought her friend was falling headlong into disaster. ‘I fear for Boris,’ she wrote. ‘In Russia poets die as an epidemic – a whole list of deaths in ten years. A catastrophe is unavoidable; first, the husband. Second, Boris has a wife and son; third, she is beautiful (Boris will be jealous) and fourth and chiefly, Boris is incapable of a happy love. For him to love means to be tortured.’

If Pasternak was tortured, so too were the women he loved. For months Zinaida would be torn by overwhelming guilt at breaking up her marriage. Boris was similarly racked over his treatment of Evgenia, writing to his parents in March 1931 that he had caused Evgenia ‘undiminished suffering’. He concluded that his wife loved him because she did not understand him and deluded himself that she needed rest and freedom – ‘complete freedom’ to realise herself professionally. He appeared to be projecting – he needed freedom from his unhappy marriage to Evgenia, while the melodrama he thrived on was exactly the creative fuel he required.

On New Year’s Day 1931, when Genrikh left for a concert tour of Siberia, Boris began obsessively calling on Zinaida, as often as three times a day, and temporarily moved out of the family’s apartment. Unable to withstand Zinaida’s vacillation any longer, after five months of ardent pursuit, he turned up at the Neigauses’ Moscow home. Genrikh opened the door to Boris and addressed him in German as ‘Der spätkommende Gast’ (the belated guest) and left to go to play at a concert.

Boris begged Zinaida once more to leave Genrikh. When Zinaida refused, he grabbed a bottle of iodine from the bathroom cupboard and in some sort of weak suicide bid, swallowed it all. His gullet burned and he started making involuntary chewing movements. When Zinaida realised what he had done she poured milk down Boris’s throat to induce vomiting – he was sick twelve times – probably saving his life. A doctor came and ‘rinsed out his insides’ as a precaution against internal burns. The doctor insisted that the exhausted Pasternak must have complete bed rest for two days and that for the first night he must not move. So he stayed at the Neigauses, in a ‘state of utter bliss’ as Zinaida tended to him, moving noiselessly and efficiently around him.

Extraordinarily, such was his reverence for the melodramatic poet, that when Genrikh returned home at two o’clock that morning and learned of what had happened, it was to his wife that he turned and said: ‘Well, are you satisfied? Has he now proved his love for you?’ Genrikh then agreed to hand Zinaida over to Boris.

‘I’ve fallen in love with Z[inaida] N[ikolaevna], the wife of my best friend, N[euhaus],’ Pasternak wrote to his parents 8 March 1931. ‘On January 1st he left for a concert tour of Siberia. I had feared this trip and tried to talk him out of it. In his absence, the thing that was inevitable and would have come about in any event, has acquired the stain of dishonesty. I’ve shown myself unworthy of N[euhaus] whom I still love and always will; I’ve caused prolonged, terrible and as yet undiminished suffering to Zhenia – and yet I am purer and more innocent than before I entered this life.’

Although Genrikh was shaken and hurt by Boris and Zinaida’s affair – he had to stop playing in the middle of one concert during his Siberian tour and left the stage in tears – he was by no means an innocent party. Zinaida’s eventual break with him was eased by Genrikh’s own infidelities. In 1929 he had sired a daughter by his former fiancée, Militsa Borodkina, and he married her in the mid-1930s.

In November 1932 Boris wrote to his parents and sisters from Moscow that Genrikh ‘is a very contradictory person, and although everything settled down last autumn he still has moods in which he tells Zina that one day in an attack of misery he’ll kill her and me. And yet he continues to meet us almost every other day, not only because he can’t forget her, but because he can’t part from me either. This creates some touching and curious situations.’ However, Sir Isaiah Berlin, a great friend of Boris and Josephine, remembered that for years after Zinaida left him, Genrikh was a frequent visitor at the couple’s dacha in Peredelkino, where Boris and Zinaida lived from 1936. After one typical Sunday lunch, Isaiah Berlin and Genrikh travelled back to Moscow together on the train. Sir Isaiah was somewhat taken aback when Genrikh turned to him and said, by way of explanation for why he had let his wife go: ‘You know, Boris is really a saint.’

Sadly though, Boris was all too human. One of the things that plagued him most during his marriage to Zinaida was his fixation with Zinaida’s teenage affair with Melitinsky. As mental torture is largely irrational, Zinaida was powerless to quell her husband’s jealous anxieties. He often became paranoid staying in hotels because the ‘semi-debauched set-up’ reminded him of Zinaida’s teenage trysts with Melitinksy. The story of Zinaida’s youthful liaison became an obsession which triggered sleeplessness and mental depression. Boris once destroyed a photograph of Melitinksy which his daughter had bought to Zinaida as a gift following her cousin’s death.

On 5 May 1931, when it was clear that Boris was not going to return to Evgenia, she and her son left Russia. They travelled to Germany, where Boris’s family – Josephine, Frederick, Lydia, Rosalia and Leonid – greeted them with open arms, intent on cocooning them with familial love. ‘Look after her,’ Boris instructed his family. ‘And we did,’ said Josephine. Frederick organised and paid for Evgenia, who had been ill with tuberculosis, to spend the summer at a sanatorium in the Black Forest while her son stayed with the family at a pension on the Starnberger See in Munich.

Understandably, Boris’s family in Germany, who loved Evgenia and adored little Evgeny, were shocked by Boris’s behaviour. They saw him as having discarded his first wife and son, and handing responsibility over to them. Leonid’s censure weighed heavily on Boris, who was left in no doubt that his family were appalled by the way he had treated Evgenia and Evgeny. On 18 December 1931, when Boris was openly living with Zinaida, his father wrote to him from Berlin:

Dear Boria!

What a lot I ought to write to you on all sorts of subjects – the terrible thing is that I know in advance that it’s a pointless waste of time, because you, and all of you, act without thinking out the consequences in advance; you’re irresponsible. And of course one’s sorry for you as well, we are especially so – what a mess you’ve got yourself into, you poor boy! And instead of doing all you can to disentangle everything and as far as possible reduce the suffering on both sides, you’re dragging it out even more and making it worse!

In early February 1932, Boris wrote Josephine a letter running over twenty pages. It is part an emotional confession of the guilt he feels at his treatment of Evgenia, part justification of his love for Zinaida – who he at one stage describes unflatteringly: ‘always comes back from the hairdresser looking terrible, like a freshly polished boot’ – part a catalogue of his neurotic mental state, which seems to veer near to madness; and part grateful homage to his sister, who Evgenia said ‘did more for her than anyone else in the world’ during the previous summer in Germany.

All is far from rosy. He admits to Josephine that he struggles with Zinaida’s oldest son, Adrian, ‘a hot-headed, selfish boy and a brutal tyrant towards his mother’. Living with another young boy makes the absence of his own son, Evgeny, even more painful. Boris also explains why, on his father’s insistence, he did not vacate the rooms in Volkhonka Street for Evgenia and her son. They had returned to Moscow on 22 December 1931 but had been forced to go and live with Evgenia’s brother for some time because it was apparently difficult for Boris to move apartments or find new ones due to restrictions imposed by the authorities and the requirements of necessary permits. This was not helped by the fact that Pasternak was already encountering restrictions due to the content of his work. ‘All this comes at a time when my work has been declared to be the spontaneous outpourings of a class enemy,’ Boris confided, ‘and I’m accused of regarding art as inconceivable in a socialist society, that is, in the absence of individualism. Verdicts like these are quite dangerous, when my books are banned from libraries.’

Probably Boris and Zinaida’s happiest time was the period they spent together in Georgia. In the summer of 1933 Pasternak had been commissioned to translate some Georgian poetry, and in order to master the language properly, and familiarise himself with the native tongue and colloquialisms, he visited the country.

To many Russians, Georgia, with its ‘abundance of sunshine, its strong emotions, its love of beauty and inborn grace of its princes and peasants alike’, was a place of enchantment and inspiration. Georgians were considered earthier and more passionate than their strait-laced Russian cousins. Pasternak made great friends with the acclaimed Georgian poets Paolo Yashvili and Titsian Tabidze. Of Yashvili he wrote: ‘Talent radiated from him. His eyes shone with an inner fire; the fire of passion had scorched his lips and the heat of experience had burnt and blackened his face, so that he looked older than his years; and as though he had been worn and tattered by life.’ Pasternak’s love affair with the Caucasus would continue throughout his life, and he referred to Georgia as his second home.

According to Max Hayward, the Oxford academic who would later be recruited to translate Doctor Zhivago into English, the poems Pasternak composed to describe his journey over the Georgian Military Highway to Tbilisi (‘probably the most breath-taking mountain road in the world’) have not been equalled in calibre since Pushkin and Lermontov wrote on the same theme. For Pasternak the Caucasian peaks, receding in an infinite panorama of unexampled grandeur, offered a simile for a vision of what a socialist future might look like. But even in this prodigious setting, Pasternak favoured images that were domestic and intimate: the rugged lower slopes, for instance, reminded him of a ‘crumpled bed’.

Pasternak’s translations of Georgian poetry would be greatly admired by Stalin – a fact that may have saved the writer’s life. Over a decade later, in 1949, as the secret police became increasingly aware of the controversial, anti-Soviet nature of the novel Pasternak was writing, a senior investigator in the prosecutor’s office claimed there were plans to arrest him. However, when Stalin was informed, the leader began to recite: ‘Heavenly colour, colour blue,’ one of the poems that Pasternak had translated. Stalin, who was born in Gori in Georgia, was moved by Pasternak’s lyrical translations of Georgian poetry. Instead of having him imprisoned or killed, as was the fate of many of Pasternak’s contemporaries, Stalin is supposed to have said: ‘Leave him in peace, he’s a cloud dweller.’ And on Pasternak’s KGB file the immortal words were stamped: ‘Leave the cloud dweller alone.’

In the early flush of happiness at his newfound stability, and possibly because he had anticipated from the start that she would play that role, Boris saw Zinaida as the facilitator of his craft. He wanted and needed her to be indispensable to his functioning as an artist. ‘You are the sister of my talent,’ he told her. ‘You give me the feeling of the uniqueness of my existence … you are the wing that protects me … you are that which I loved and saw, and what will happen to me.’

When Evgenia finally cleared her belongings from the Pasternak apartment on Volkhonka Street in September 1932, and Boris moved back in with Zinaida, they found the house in a dilapidated condition. The roof leaked, rats had gnawed and ripped the skirting boards, and many window panes were cracked and missing. A month later, when Boris returned from a three-day trip to Leningrad, Zinaida had wrought an amazing transformation. The windows were repaired. She had hung curtains, fixed herniated mattresses and fashioned a new sofa cover from one of the spare curtains. The floors were polished, the windows were washed and sealed for the winter. Zinaida had even added various rugs, two cupboards and an upright piano which, extraordinarily, came from her ex-in-laws, Neigaus’s parents, who had moved to Moscow and were now living with the abandoned Genrikh.

In 1934, Boris married Zinaida in a civil ceremony. So caught up was he in his fantasy image of Zinaida that he failed to see her shortcomings. Zinaida may have been a dab hand in the house, but for a man as impassioned as Boris, she was not the champion and soul mate he yearned for. Not only did Zinaida not understand his poetry, she could not fathom her husband’s creative courage. Worse, she increasingly feared his poetry’s power to upset the equilibrium of her well-managed household by provoking official disfavour.

A considerable strain in their relationship was caused by the arrest of Boris’s friend, the poet Osip Mandelstam. One evening in April 1934, Boris bumped into him on a Moscow boulevard. To his consternation – even ‘the walls have ears’ he warned – Mandelstam, a fearsome critic of the regime, proceded to recite an incredibly scathing poem he had written about Stalin. (Lines included: ‘His fingers are fat as grubs,/And the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips …/His cockroach whiskers leer,/And his boot tops gleam.’)

‘I didn’t hear this; you didn’t recite this to me,’ Boris said to him, agitated. ‘Because, you know, very dangerous things are happening now. They’ve begun to pick people up.’ These were the early ominous beginnings of what would become the Great Terror, when hundreds of thousands of people accused of various political crimes – espionage, anti-Soviet agitation and conspiracies to prepare uprisings and coups – were quickly executed or sent to labour camps. Boris told Mandelstam that his poem was tantamount to suicide and implored him not to recite it to anyone else. Mandelstam did not listen and inevitably, was betrayed. On 17 May he was arrested by the NKVD.

When he found out, Pasternak valiantly tried to help his friend. He appealed to the politician and writer Nikolai Bukharin, recently appointed editor of Izvestiya newspaper, who had commissioned some of Pasternak’s Georgian translations. In June, Bukharin sent Stalin a message with the postscript: ‘I’m also writing about Mandelstam because B. Pasternak is half crazy about Mandelstam’s arrest, and nobody knows anything …’

Pasternak’s entreaties paid off. Instead of being sent to almost certain death in a forced labour camp, Mandelstam was sentenced to three years’ internal exile in the town of Cherdyn, in the north-east Urals – Stalin having issued a chilling command that was passed down the chain: ‘Isolate but preserve’. Boris was astonished to be called to the communal telephone in the hallway at Volkhonka Street and told that it was Stalin on the line. According to Mandelstam’s wife, Nadezhda:

Stalin said that Mandelstam’s case was being reconsidered and that everything would be all right with him. An unexpected reproach followed – why didn’t Pasternak turn to writer’s organisations or ‘to me’ to plead for Mandelstam? Pasternak’s answer was ‘writer’s organisations haven’t been dealing with this since 1927, and if I hadn’t pleaded, you might not have got to know about it’.

Stalin stopped him with a question: ‘But he is an expert, a master, isn’t he?’

Pasternak answered, ‘That’s not the point.’

‘Then what is the point?’ Stalin asked.

Pasternak said that he would like to meet and speak with him.

‘What about?’

‘About life and death.’

Stalin hung up the phone.

When word of the telephone conversation with Stalin got out, Pasternak’s critics claimed he should have defended his friend’s talent more vigorously. But others, including Nadezhda and Osip Mandelstam, felt happy with Boris’s response. They understood his caution and thought he had done well not to be lured into the trap of admitting that he had, indeed, heard Osip’s ‘Stalin Epigram’. ‘He was quite right to say that whether I am a master or not is beside the point,’ Osip declared. ‘Why is Stalin so afraid of a master? It’s like a superstition with him. He thinks we might put a spell on him like shamans.’

In 1934, Pasternak was invited to the First Congress of the Soviet Writers’ Union. He was disquieted by the official praise and by efforts to turn him into a literary public hero who had not been politically compromised. His work was increasingly being recognised by the West and he felt uncomfortable with this attention. Ironically, his writing was becoming more difficult to publish, so he concentrated on translation work. In 1935 he wrote to his Czech translator: ‘All this time, beginning with the Writers’ Congress in Moscow, I have had a feeling that, for purposes unknown to me, my importance is being deliberately inflated … all this by somebody else’s hands without asking my consent. And I shun nothing in this whole world more than fanfare, sensationalism, and so-called cheap “celebrity” in the press.’

Pasternak and his family now accepted accommodation in the Writers’ Union apartment block on Lavrushinsky Lane in Moscow and a dacha in Peredelkino. Pasternak acquired the rights to one of the properties, shaded by tall fir trees and pine trees, with the money he had received from his Georgian translations. In 1936 he still held high hopes that his parents would return to Russia and live with him there. This writers’ colony, built on the former estate of a Russian nobleman outside Moscow, had been created to reward the Soviet Union’s most prominent authors with a retreat that provided bucolic escape from their city apartments. Apparently, when Stalin heard that the colony was to be called Peredelkino, from the Russian verb peredelat, which means to re-do, he suggested it would be better to call is Perepiskino, from the verb to rewrite. Kornei Chukovsky, the Soviet Union’s best-loved children’s author, described the system of the writers’ colony as ‘entrapping writers with a cocoon of comforts, surrounding them with a network of spies’.

Such state controls did not sit comfortably with Pasternak. Nikolai Bukharin once said that Pasternak was ‘one of the most remarkable masters of verse of our time, who has not only strung a whole row of lyrical pearls on to the necklace of his talent, but has produced a whole number of revolutionary works marked by deep sincerity’. But Pasternak pleaded: ‘Do not make heroes of my generation. We were not: there were times when we were afraid and acted from fear, times when we were betrayed.’

At a writers’ meeting in Minsk, Pasternak told his colleagues that he fundamentally agreed with their view of literature as something that could be produced like water from a pump. He then put forward the view for artistic independence, before announcing that he would not be part of the group. Almost an act of literary suicide, the audience were stunned. No one risked so public a speech as this until after Stalin’s death. After this, there were no more efforts to draw Pasternak into the literary establishment. For the main part he was left alone, while the purges on writers continued with terrifying frequency and force. In October 1937, his great friend Titsian Tabidze was expelled from the Union of Georgian Writers and arrested. Paolo Yashvili, rather than be forced into denouncing Tabidze, shot himself dead at the offices of the Writers’ Union.

When in 1937 Osip Mandelstam was allowed to return from exile, Zinaida feared having any contact with him and his wife, in case it threatened her family’s safety. Boris abhorred what he saw as such moral cowardice. On several occasions, Zinaida prevented him from receiving friends and colleagues at Peredelkino for fear of contagion by association. Once, when Osip and Nadezhda turned up at the Peredelkino dacha, Zinaida refused to receive them. She forced her husband back onto the verandah to tell his friends lamely and with considerable embarrassment: ‘Zinaida seems to be baking pies.’ According to Olga Ivinskaya, Zinaida always ‘loathed’ the Mandelstams, who she considered were compromising her ‘loyal’ husband. Olga claimed that Zinaida was famous ‘for her immortal phrase: “My sons love Stalin most of all – and then their Mummy.”’

Zinaida’s antipathy towards the Mandelstams would have incensed Boris and caused further rifts between them. Boris’s belief in his destiny at this time gave him a certain fearlessness that Zinaida could not begin to match. She later admitted: ‘no one could know on whose head the rock would fall and yet he showed not an ounce of fear’.

On 28 October 1937, Boris’s friend and neighbour at Peredelkino, Boris Pilnyak, was arrested by the secret police. His typewriter and the manuscript of his new novel were confiscated and his wife arrested. The NKVD report implicated Boris too: ‘Pasternak and Pilnyak held secret meetings with [the French author André] Gide, and supplied him with information about the situation in the USSR. There is no doubt that Gide used this information in his book attacking the USSR.’ In April, after a trial lasting just fifteen minutes, Pilnyak was condemned to death and executed. His final words to the court after months of imprisonment were: ‘I have so much work to do. A long period of seclusion has made me a different person; I now see the world through new eyes. I want to live, to work, to see in front of me paper on which to write a work that will be of use to the Soviet people.’

Another of Pasternak’s friends, the playwright A. N. Afinogenov, who had been expelled from the Communist Party and from the Writers’ Union for daring to criticise the dictatorship through his work, was abandoned by all his friends except Boris. On 15 November he wrote: ‘Pasternak is going through a hard time now; he has constant quarrels with his wife. She tries to make him attend all the meetings; she says he doesn’t think about his children, and his reserved behaviour seems suspicious and he will be arrested if he continues to be aloof.’

Pasternak confided to the literary scholar and critic Anatoly Tarasenkov in 1939: ‘In those horrendous, blood-stained years anyone might have been arrested. We were shuffled like a pack of cards. I have no wish to give thanks, in a philistine way, for remaining alive while others did not. There is a need for someone to show grief, to go proudly into mourning, to react tragically – for someone to be tragedy’s standard bearer.’

In spite of unimaginable pressures, Pasternak stayed true to himself in his professional life. His loyalty to his friends was unwavering. Osip Mandelstam was again arrested in 1938 and eventually died in the gulag. The only person to visit Mandelstam’s widow after his death was Boris. ‘Apart from him no one had dared to come and see me,’ said Nadezhda.

It is almost miraculous that Pasternak was not exiled or killed during these years. Why did Stalin save his ‘cloud dweller’? Another quirk that may have saved the writer’s life was that Stalin believed the poet had prescient powers, some sort of second sight.

In the early hours of 9 November 1932, Stalin’s wife, Nadya Alliluyeva, committed suicide. At a party the previous evening, a drunken Stalin had flirted in front of the long-suffering Nadya and had publicly diminished her. That night, when she heard rumours that her husband was with a lover, she shot herself in the heart.

The death certificate, signed by compliant doctors, said that the cause of death was appendicitis (as suicide could not be acknowledged). Soviet ritual required collective letters of grief from different professions. Almost the whole of the literary establishment – thirty-three writers – signed a formal letter of sympathy to Stalin. Pasternak refused to add his name to it. Instead, he wrote his own letter in which he hinted that he shared some mythical communion with Stalin, empathising with his motives, emotions and presumed sense of guilt.

In his letter, Boris wrote: ‘I share the feelings of my comrades. On the evening before, I found myself thinking deeply and continually about Stalin for the first time from the point of view of an artist. In the morning I read the news, and I was shaken just as if I had been present, and as though I had lived through it, as though I had seen it all.’ It appears that Stalin may well have believed that Pasternak was a ‘poet-seer’ who had prophetic powers. According to the émigré scholar Mikhail Koryakov, writing in the American Russian-language newspaper Novy Zhurnal: ‘from that moment onwards … it seems to me, Pasternak, without realising it, entered the personal life of Stalin and became some part of his inner world’.

As neither Pasternak nor an increasingly nervous Zinaida could have known about this golden protection from on high, that he continued to work on Doctor Zhivago, drafting the structure throughout the mid-thirties, seems almost to be a further act of literary suicide. Looking back, he explained to the Czech poet Vitezslav Nezval: ‘Following the October Revolution things were very bad for me. I wanted to write about this. A book in prose about how bad things were. A straightforward and simple narrative. You understand, sometimes a man must force himself to stand on his head.’

Pasternak forced himself to stand on his head yet again in 1937 when the Writers’ Union asked him to sign a joint letter endorsing the death sentence of a high-ranking official plus several other prominent military figures on charges of espionage. Pasternak refused. Incensed, he told the union: ‘the lives of people are disposed of by the government, not by private individuals. I know nothing about them [the accused]. How can I wish their death? I did not give them life. I can’t be their judge. I prefer to perish together with the crowd, with the people. This is not like signing complimentary tickets to the theatre.’ Pasternak then penned a letter to Stalin: ‘I wrote that I had grown up in a family where Tolstoyan convictions were very strong. I had imbibed them with my mother’s milk, and he could dispose of my life. But I did not consider I was entitled to sit in judgement over the life and death of others.’

Tensions now erupted with Zinaida, who argued with Boris and urged him to sign the Writers’ Union letter, fearing the consequences for their family if he did not. His adherence to his beliefs made him seem selfish in her eyes. Zinaida was pregnant, which sadly did not seem cause for great celebration at the time. Their marriage was struggling due to their extreme ideological differences and to the political pressures of the times. When Boris first learned of Zinaida’s pregnancy, he wrote to his parents that her ‘present condition is entirely unexpected, and if abortion weren’t illegal, we’d have been dismayed by her insufficiently joyful response to the event, and she’d have had the pregnancy terminated.’ Zinaida later wrote that she very much wanted, ‘Boria’s child’, but her acute fear that Boris could be arrested at any moment made it hard to carry the pregnancy. So convinced was Zinaida that Boris was likely to be arrested at any moment that she had even packed a small suitcase for this emergency.

‘My wife was pregnant. She cried and begged me to sign, but I couldn’t,’ wrote Boris. ‘That day I examined the pros and cons of my own survival. I was convinced I would be arrested – my turn had come. I was prepared for it. I abhorred all this blood and I couldn’t stand it any longer. But nothing happened. I was later told that my colleagues had saved me – at least indirectly. Quite simply no one dared to report to the hierarchy that I hadn’t signed.’

It offers insight into his bullish mentality that, fully aware that he might be shot or seized that night, Pasternak wrote: ‘We expected that I would be arrested that night. But, just imagine, I went to bed and at once fell into a blissful sleep. Not for a long time had I slept so well and peacefully. This always happens to me after I have taken some irrevocable step.’

On 15 June Pasternak saw his signature displayed on the front page of the Literaturnaya Gazeta, along with those of forty-three other writer colleagues. He rushed from Peredelkino to Moscow to protest to the secretariat of the Writers’ Union about the unauthorised inclusion of his signature, but by then the heat had gone and no one took much notice. Again, against his better instincts, he had been saved.

Boris’s dear friend Titsian Tabidze was not so lucky. After his early morning arrest on 11 October 1937, he had been charged with treason, sent to the gulag and tortured. He was executed two months later, though no announcement was made at the time. It was not until after Stalin’s death in the mid-1950s that the truth emerged. Boris mourned his friend keenly, remaining loyal to Titsian’s wife, Nina, and daughter Nita. All through the 1940s, when they all prayed that Titsian was alive somewhere in Siberia, Boris assisted the family financially, sending them all the royalties from his translations of Georgian poetry and regularly inviting them to stay at Peredelkino. Titsian’s crime was similar to Pasternak’s. He had written with conscience about Russia, and been openly defiant at a time when literary modernity was crushed by the Soviet state. After an attack on Titsian in the press, Boris had urged him in a letter: ‘Rely only on yourself. Dig more deeply with your drill without fear or favour, but inside yourself, inside yourself. If you do not find the people, the earth and the heaven there, then give up your search, for then there is nowhere else.’

Pasternak’s second son, Leonid, was born just into the new year, 1938. Boris wrote to his family in Berlin on New Year’s Day: ‘The boy was born lovely and healthy and seems very nice. He managed to appear on New Year’s night with the last 12th strike of the clock. And he was mentioned in the statistics report of the maternity hospital as “the first baby, born at 0 o’clock of the 1st January 1938”. I named him Leonid in your honour. Zina suffered a lot in childbirth, but she seems to be created for difficulties and bears them easily and almost silently. If you’d like to write to her and can do so without feeling obligated, please write.’

It is a mark of how far his marriage to Zinaida was unravelling that, eighteen months earlier, while Zinaida organised the house move to Peredelkino from Moscow all by herself – moving her sons and all the family’s furniture – Boris went to stay with his former wife Evgenia, at her Tverskoi Boulevard home. ‘He was very drawn to young Zhenya and to me. He lived a few days with us and entered our lives so naturally and easily, as though he had only been away by chance,’ Evgenia later wrote to her friend Raisa Lomonosova of Boris’s stay with her that summer; ‘But despite the fact that, in his words, he is sick to death of that life, he will never have the courage to break with her [Zinaida]. And it is pointless him tormenting me and reviving old thoughts and habits.’

For Boris, Evgenia’s artistic temperament suddenly seemed less stifling, compared with Zinaida’s bland domesticity. It gave rise to a nostalgia in Boris for his first family and underlined his dour sense of duty to his second. He found Zinaida’s personality ‘challenging’ and ‘inflexible’ and was by now aware that their characters were too different for them to reside together in any sort of harmony. Years later, Zinaida’s daughter-in-law, Natasha (who married Boris and Zinaida’s son, Leonid), said of her mother-in-law: ‘She had a very rigid character. She was practical and disciplined. She would say “now we go to lunch” and everyone would sit down. She was the head of the table, like a captain running a ship.’

Pasternak’s friend the poet Anna Akhmatova observed that at the beginning, being blindly in love, Boris failed to see what others perceived: that Zinaida was ‘coarse and vulgar’. To Boris’s literary friends, she did not share his desire for spiritual and aesthetic pursuits, preferring to play cards and chain-smoke into the early hours. But Akhmatova correctly predicted that Boris would never leave Zinaida because he ‘belonged to the race of conscientious men who cannot divorce twice’. It was inevitable that his emotional journey was not yet over. He was about to meet Olga, the soul mate who would be his Lara, for whom he had longed all his life.