Читать книгу Lara: The Untold Love Story That Inspired Doctor Zhivago - Anna Pasternak - Страница 9

PROLOGUE Straightening Cobwebs

ОглавлениеIt is almost impossible, by today’s standards of celebrity, to comprehend the level of fame that Boris Pasternak engendered in Russia from the 1920s onwards. Pasternak may be most famous in the West for writing the Nobel Prize-winning love story Doctor Zhivago, yet in Russia he is primarily recognised, and still hugely feted, as a poet. Born in 1890, his reputation escalated during his early thirties; soon he was filling large auditoriums with young students, revolutionaries and artists who gathered to hear recitals of his poems. If he paused for effect or for a momentary memory lapse, the entire crowd continued to roar the next line of his verse in unison back at him, just as they do at pop concerts today.

‘There was in Russia a very real contact between the poet, and the public, greater than anywhere else in Europe,’ Boris’s sister, Lydia, wrote of this time; ‘certainly far greater than is ever imaginable in England. Books of poetry were published in enormous editions and were sold out within a few days of publication. Posters were stuck up all over the town announcing poets’ gatherings and everyone interested in poetry (and who in Russia did not belong to this category?) flocked to the lecture room or forum to hear his favourite poet.’ The writer had immense influence in Russian society. In a time of unrest, with an absence of credible politicians, the public looked to its writers. The influence of literary journals was prodigious; they were powerful vehicles for political debate. Boris Pasternak was not only a popular poet hailed for his courage and sincerity. He was revered by a nation for his fearless voice.

From his early years Pasternak longed to write a great novel. He told his father, Leonid, in 1934: ‘Nothing I have written so far is of any significance. Hurriedly I am trying to transform myself into a writer of a Dickensian kind, and later – if I have enough strength to do it – into a poet in the manner of Pushkin. Do not imagine that I dream of comparing myself with them! I am naming them simply to give you an idea of my inner change.’ Pasternak dismissed his poetry as too easy to write. He had enjoyed unexpected, precocious success with his first published volume of poetry, Above the Barriers, in 1917. This became one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Critics praised the book’s biographical and historical material, marvelling at the contrasting lyrical and epic qualities. A. Manfred, writing in Kniga I revolyutsiya, observed a new ‘expressive clarity’ and of the author’s prospects of ‘growing into the revolution’. Pasternak’s second collection of twenty-two poems, My Sister, Life, published in 1922, received unprecedented literary acclaim. The exultant mood of the collection delighted readers as it conveyed the elation and optimism of the summer of 1917. Pasternak wrote that the February Revolution had happened ‘as if by mistake’ and everyone suddenly felt free. This was Boris’s ‘most celebrated book of poems’, observed his sister Lydia. ‘The more sophisticated younger generation of literary Russians went wild over the book.’ They considered that he wrote the finest love poetry, in thrall to his intimate imagery. After reading My Sister, Life, the poet Osip Mandelstam declared: ‘To read Pasternak’s verse is to clear your throat, to fortify your breathing, to fill your lungs: surely such poetry could provide a cure for tuberculosis. No poetry is more healthful at the present moment! It is koumiss [mare’s milk] after evaporated milk.’

‘My brother’s poems are without exception strictly rhythmical and written mostly in classical metre,’ Lydia wrote later. ‘Pasternak, like Mayakovsky, the most revolutionary of Russian poets, has never in his life written a single line of unrhythmic poetry, and this is not because of pedantic adherence to obsolete classical rules, but because instinctive feeling for rhythm and harmony were inborn qualities of his genius, and he simply could not write differently.’ In a poem written shortly after My Sister, Life was published, Boris bids farewell to poetry: ‘I will say so long to verse, my mania – I have an appointment with you in a novel.’ Still though, he glorified prose-writing as being too difficult. Yet the two modes of writing actually shared an intrinsic relationship in his work, regardless of the genre. In his autobiography Safe Conduct, published in 1931, a mannered account of his early life, travels and personal relationships, he wrote: ‘We drag everyday things into prose for the sake of poetry. We draw prose into poetry for the sake of music. This, then, I called art, in the widest sense of the word.’

It was in 1935 that Pasternak first spoke of his intent to fulfil his artistic potential by writing an epic Russian novel. And it was to my grandmother, his younger sister, Josephine Pasternak*, that he first confided his ideas at their last meeting at Friedrichstrasse station in Berlin. Boris told Josephine that the seeds of a book were germinating in his mind; an iconic, enduring love story set in the period between the Russian Revolution and the Second World War.

Doctor Zhivago is based on Boris’s relationship with the love of his life, Olga Vsevolodovna Ivinskaya, who was to become the muse for Lara, the novel’s spirited heroine. Central to the novel is the passionate love affair shared by Yury Zhivago, a doctor and poet (a nod to the writer Anton Chekhov, who was also a doctor) and Lara Guichard, the heroine, who becomes a nurse. Their love is tormented as Yury, like Boris, is married. Yury’s diligent wife, Tonya, is based on Boris’s second wife, Zinaida Neigaus. Yury Zhivago is a semi-autobiographical hero; this is the book of a survivor.

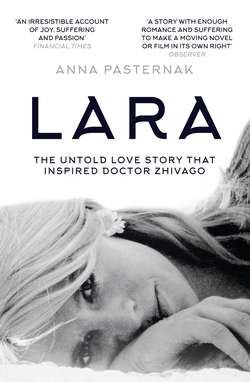

Doctor Zhivago has sold in its millions yet the true love story behind it has never been fully explored before. The role of Olga Ivinskaya in Boris’s life has been consistently repressed both by the Pasternak family and Boris’s biographers. Olga has regularly been belittled and dismissed as an ‘adventurous’, ‘a temptress’, a woman on the make, a bit part in the history of the man and his book. When Pasternak started writing the novel, he had not yet met Olga. Lara’s teenage trauma of being seduced by the much older Victor Komarovsky is a direct echo of Zinaida’s experiences with her sexually predatory cousin. However, as soon as Boris met and fell in love with Olga, his Lara changed and flowered to completely embody her.

Historically both Olga and her daughter, Irina, have received a bad rap from my family. The Pasternaks have always been keen to play down the role of Olga in Boris’s life and literary achievements. They held Boris in such high esteem that for him to have had two wives – Evgenia and Zinaida – and a public mistress was indigestible to their staunch moral code. By accepting Olga’s place in Boris’s life and affections, they would have had to further acknowledge his moral fallibility.

Shortly before she died, Josephine Pasternak told me furiously: ‘It is a mistaken idea that this … acquaintance ever appeared in Zhivago.’ In fact, her feelings for ‘that seductress’ were so strong that she refused to ever sully her lips with her name. She was in denial, blinded by her reverence for her brother. Even though in Boris’s last letter to her, written on 22 August 1958, he tells his sister that he hopes to travel in Russia ‘with Olga’, underlining the importance of his mistress in his life, Josephine would not acknowledge her existence. Evgeny Pasternak, Boris’s son by his first wife, was more pragmatic. He may not have liked Olga, displaying little warmth towards her, yet he was more accepting of the situation. ‘It was lucky that my father had the love of Lara,’ he told me shortly before he died in 2012, aged eighty-nine. ‘My father needed her. He would say “Lara exists, go and meet her.” This was a compliment.’

It was not until 1946 that fate intervened, when Boris was fifty-six years old. As he later wrote in Doctor Zhivago, ‘From the bottom of the sea the tide of destiny washed her up to him’. It was at the offices of the literary journal Novy Mir that he met thirty-four-year-old Olga Ivinskaya, an editorial assistant. She was blonde and cherubically pretty, with cornflower-blue eyes and enviably translucent skin. Her manner was beguiling – highly strung and intense, yet with an underlying fragility, hinting at the durability of a survivor. She was already a dedicated fan of Pasternak the ‘poet hero’. Their attraction was mutual and instant, and it is easy to see why they were drawn to each other. Both were melodramatic romantics given to extraordinary flights of fantasy. ‘And now there he was at my desk by the window,’ she later wrote, ‘the most unstinting man in the world, to whom it had been given to speak in the name of the clouds, the stars and the wind, who had also found eternal words to say about man’s passion and woman’s weakness. People say that he summons the stars to his table and the whole world to the carpet at his bedside.’

Having become fascinated with my great-uncle’s love story, I feel passionately that if it were not for Olga, not only would Doctor Zhivago never have been completed but it would never have been published. Olga Ivinskaya paid an enormous price for loving ‘her Boria’. She became a pawn in a highly political game. Her story is one of unimaginable courage, loyalty, suffering, tragedy, drama and loss.

From the mid-1920s, as Stalin came to power after Lenin’s death, it was established that communism would not tolerate individual tendencies. Stalin, an anti-intellectual, described writers as the ‘engineers of the soul’ and regarded them as having an influential potency that needed to be channelled into the collective interests of the state. He began his drive for collectivisation and with it mass terror. The atmosphere for poets and authors, expressing their own individual creativity, became unbearably oppressive. After 1917 nearly 1,500 writers in the Soviet Union were executed or died in labour camps for alleged infractions. Under Lenin, indiscriminate arrests had become part of the system, as it was believed to be in the interest of the state to incarcerate a hundred innocent people rather than let one enemy of the regime go free. The atmosphere of fear, of people informing on colleagues or former writer friends, was actively encouraged in Stalin’s new stifling regime where everyone was fighting to survive. Many writers and artists, terrified of persecution, committed suicide. Where Pasternak’s semi-autobiographical hero Yury Zhivago dies in 1929, Boris himself survived, though refusing to kowtow to the literary and political diktats of the day.

Stalin, who had a special admiration for Boris Pasternak, did not imprison the controversial writer; instead he harassed and persecuted his lover. Twice Olga Ivinskaya was sentenced to periods in labour camps. She was interrogated about the book Boris was writing, yet she refused to betray the man she loved. The leniency with which Stalin treated Pasternak did not diminish the author’s outrage towards his country’s leader; he was, he lamented, ‘a terrible man who drenched Russia in blood’. During this time an estimated 20 million people were killed, and 28 million deported, most of whom were put to work as slaves in the ‘correctional labour camps’. Olga was one of the millions sent gratuitously to the gulag, precious years of her life stolen from her due to her relationship with Pasternak.

In 1934 Alexei Surkov, a poet and budding party functionary, gave a speech at the First Congress of the Soviet Writers’ Union that summed up the Soviet view: ‘The immense talent of B. L. Pasternak will never fully reveal itself until he has attached himself fully to the gigantic, rich and radiant subject matter [offered by] the Revolution; and he will become a great poet only when he has organically absorbed the Revolution into himself.’ When Pasternak saw the reality of the Revolution, that his beloved Russia had had its ‘roof torn off’, as he put it, he wrote his own version of history in Doctor Zhivago, defiantly criticising the tyrannical regime. In it Yury says to Lara:

Revolutionaries who take the law into their own hands are horrifying, not as criminals, but as machines that have got out of control, like a run-away train … But it turns out that those who inspired the revolution aren’t at home in anything except change and turmoil: that’s their native element; they aren’t happy with anything that’s less than on a world scale. For them, transitional periods, worlds in the making, are an end in themselves. They aren’t trained for anything else, they don’t know about anything except that. And do you know why there is this incessant whirl of never-ending preparations? It’s because they haven’t any real capacities, they are ungifted.

In the last century few literary works created such a furore as Doctor Zhivago. It was not until 1957, over twenty years after Pasternak first confided in Josephine, that the book was published, initially in Italy. Despite being an instant, international bestseller, and even though Pasternak was then seen as Russia’s ‘greatest living writer’, it was over thirty years later, in 1988, that his book, regarded as anti-revolutionary and unpatriotic, was legitimately published in his adored ‘Mother Russia’. The cultural critic Dmitry Likhachev, who was considered the world’s foremost expert in Old Russian language and literature in the late twentieth century, said that Doctor Zhivago was not really a traditional novel but was rather ‘a kind of autobiography’ of the poet’s inner life. The hero, he believed, was not an active agent but a window on the Russian Revolution.

In 1965 David Lean made film history with his adaptation of Pasternak’s novel, in which Julie Christie was cast as the heroine, Lara, and Omar Sharif as the hero, Yury Zhivago. The film won five Academy Awards and was nominated for five more. Lean’s Hollywood classic has left millions of viewers with images as magic and endurable as Pasternak’s prose. It is the eighth highest-grossing film in American film history. Robert Bolt, who won an Academy Award for the screenplay, said of adapting Pasternak’s work: ‘I’ve never done anything so difficult. It’s like straightening cobwebs.’ Omar Sharif said of it: ‘Doctor Zhivago encompasses but does not overwhelm the human spirit. That is Boris Pasternak’s gift.’ Of the enduring quality of the story, he concluded: ‘He proves that true love is timeless. Doctor Zhivago was and always will be a classic for all generations.’

There is a Russian proverb: ‘You cannot know Russia through your head. You can only understand her through your heart.’ When I visited Russia for the first time, walking around Moscow was like being haunted, as I had the sense not of being a tourist but of coming home. It was not that Moscow was familiar to me but it did not feel foreign either. I marched through the snow one wintry February night, up the wide Tverskaya Street, to dinner at the Café Pushkin restaurant, acutely conscious that Boris and Olga had used the same route many times during their courtship, over sixty years earlier, treading the very same pavements.

Sitting amid the flickering candlelight of the Café Pushkin, which is styled to resemble a Russian aristocrat’s home of the 1820s – with its galleried library, book-lined walls, elaborate cornices, frescoed ceilings and distinct grandeur – I felt the hand of history gently resting on me. The restaurant is close to the old offices of Novy Mir, Olga’s former workplace on Pushkin Square. I imagined Olga and Boris walking past, their heads bowed low and close against the snow, wrapped in heavy coats, their hearts full of desire.

Five years later, on another visit to Moscow, I went to the Pushkin statue, erected in 1898, where Boris and Olga frequently rendezvoused during the early stages of their relationship. It was here that Boris first confessed the depth of his feelings to Olga. The vast statue of Pushkin was moved in 1950 from one side of Pushkin Square to the other, so they would have started their courtship on the west side of the square and moved to the east side in 1950 where I stood, looking up at the giant bronze folds of Pushkin’s majestic cape tumbling down his back. My Moscow guide, Marina, a fan of Putin and the current regime, looked at me standing under Pushkin’s statue, envisaging Boris at that very spot, and said: ‘Boris Pasternak is an inhabitant of heaven. He is an idol for so many of us, even those who are not interested in poetry.’

This reverential view echoed my meeting with Olga’s daughter, Irina Emelianova, in Paris a few months earlier. ‘I thank God for the chance to have met this great poet,’ she told me. ‘We fell in love with the poet before the man. I always loved poetry and my mother loved his poetry, just as generations of Russians have. You cannot imagine how remarkable it was to have Boris Leonidovich [his Russian patronymic name†] not just in the pages of our poetry but in our lives.’

Irina was immortalised by Pasternak as Lara’s daughter, Katenka, in Doctor Zhivago. Growing up, Irina became incredibly close to Boris. He loved her as the daughter he never had and was more of a father figure to her than any other man in her life. Irina got up from the table we were sitting at and retrieved a book from her well-stocked shelves. It was a translation of Goethe’s Faust which Boris had given her, and on the title page was a dedication in Boris’s bold, looping handwriting in black ink, ‘like cranes soaring over the page’ as Olga once described it. Inside, Boris had written in Russian to the then seventeen-year-old Irina: ‘Irochka, this is your copy. I trust you and I believe in your future. Be bold in your soul and mind, in your dreams and purposes. Put your faith in nature, in the spirit of your destiny, in events of significance – and only in such few people as have been tested a thousand times, and are worthy of your confidence.’

Irina proudly read the final inscription to me. Boris had written: ‘Almost like a father, Your BP. November 3, 1955, Peredelkino.’ As she ran her hand affectionately across the page, she said sadly: ‘It’s a shame that the ink will fade.’

It was a timeless moment, as we both stared at the page, considering perhaps that everything precious in life eventually ebbs away. Irina closed the book, straightened her shoulders, and said: ‘You cannot imagine how knowing Boris Pasternak altered our lives. I would go and listen to his poetry recitals and I was the envy of my friends at school and my English professor and the teachers. “You know Boris Leonidovich?” they would ask me in awe. “Can you get the latest poem from him?” I would ask his typist if we could just have one line of his verse and sometimes he would distribute a poem for me to hand out. That gave me incredible prestige at school and in a way his glory rubbed off on me.’

The Russian people’s reverence for Pasternak, which remains to this day, is not just because of the enduring power of his writing, but because he never wavered in his loyalty to Russia. His great love was for his Motherland; in the end, that was stronger than everything. He renounced the Nobel Prize for Literature when the Soviet authorities threatened that if he left his country, he would not be allowed to return. And he never became an émigré, refusing to follow his parents to Germany, then England, after the 1917 Revolution.

When I went to Peredelkino, to the writer’s colony, a fifty-minute drive from central Moscow, where Boris spent nearly two decades writing Doctor Zhivago, I felt a profound sadness. As I sat at Boris’s desk in his study on the upper floor of his dacha, I traced the faint ring marks his coffee cups had left on the wood over fifty years earlier. Icicles hung outside the window, reminiscent of David Lean’s film: I was reminded of Varykino, the abandoned estate in the novel, where Yury spends his last days with Lara, dazzling in the sun and snow; the lacework of hoar frost on the frozen window panes; the crystalline magic conjured on screen; Julie Christie, embodying his Lara, effortlessly beautiful beneath her fur hat. I thought of my great-uncle Boris looking out of the window, across the garden he adored, past the pine trees to the Church of Transfiguration. In the distance lies Peredelkino cemetery, where he is buried. Earlier that day, my father, Boris’s nephew, and I had trudged through deep snowdrifts in the cemetery to visit his grave, where I was touched to find a bouquet of frozen long-stemmed pink roses carefully placed against his headstone. They must have been left there by a fan. I was struck that no words of Boris’s adorn his grave. Just his face etched into the stone. Powerful in its simplicity, nothing more needs to be said.

I leaned back in Boris’s chair in his study and considered how often he must have turned back from the undulating view to his page (he wrote in longhand), inspired, to create scenes of longing between Yury and Lara. When I was there the snow was gently falling outside, enhancing the stillness. The room is almost painful in its plainness. In one corner stands a small wrought-iron bed with a sketch of Tolstoy hanging above it and family drawings by Boris’s father, Leonid, to each side. With its drab grey patterned cover and the reddish brown cut-out square of carpet close by, the bed would not have been out of place in a monastic cell. Opposite, a bookcase: the Russian Bible, works by Einstein, the collected poems of W. H. Auden, T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, Emily Dickinson, novels by Henry James, the autobiography of Yeats and the complete works of Virginia Woolf (Josephine Pasternak’s favourite author), along with Shakespeare and the teachings of Jawaharlal Nehru. Facing the desk, on an artist’s easel, a large black and white photograph of Boris himself. Wearing a black suit, white shirt and dark tie, I considered that he looked about my age, mid-forties. Pain, passion, determination, resignation, fear and fury emanate from his eyes. His lips are almost pursed, set with conviction. There was nothing soft or yielding about his sanctuary; he saved his sensuousness for his prose.

I thought about Boris’s courage, a courage that meant he could sit there and write his truth about Russia. How he defiantly stared the Soviet authorities in the face, and how persecution and the threat of death eventually took its toll. How, despite outliving Stalin, in spite of his colossal literary achievements, he lived his last years here in imposed isolation, the Soviet authorities watching and monitoring his every move. His study became his personal quarantine: writing upstairs; his wife Zinaida downstairs, chain-smoking as she played cards or watched the clunky antique Soviet television, one of the first ever made.

And I imagined his lover Olga Ivinskaya, in the last years of Boris’s life, anxiously waiting for him every afternoon to join her in the ‘Little House’ across the lake at Izmalkovo, a kilometre away. Here she would soothe and support, encourage and type up his manuscripts. Not visible in his home by way of cherished photograph or painting, her absence is jarring. For what is the love story in Doctor Zhivago if it is not his passionate cri de coeur to Olga? I thought of her endlessly reassuring him of his talent when the authorities taunted that he had none; how she brought fun and tenderness into his life when everything else was so strategic, harsh, political and fraught. How she loved him but, just as crucially, how she understood him. Many artists are selfish and self-indulgent, as he was. It would be easy to conclude that Boris used Olga. It is my intention to show that, rather, his great omission was that he did not match her cast-iron loyalty and moral fortitude. He did not do the one thing in his power to do: he did not save her.

Looking around his study for the last time, I knew that I wanted to write a book which would try to explain why he performed this uncharacteristic act of moral cowardice, putting his ambition before his heart. If I could understand why he behaved as he did and appreciate the extent of his suffering and self-attack, could I forgive him for letting himself and his true love down? For not publicly claiming or honouring Olga – for not marrying her – when she was to risk her life loving him? As he writes in Doctor Zhivago: ‘How well he loved her, and how loveable she was in exactly the way he had always thought and dreamed and needed … She was lovely by virtue of the matchlessly simple and swift line which the Creator at a single stroke had drawn round her, and in this divine outline she had been handed over, like a child tightly wound up in a sheet after its bath, into the keeping of his soul.’

* Josephine married her cousin, Frederick Pasternak, hence the continuation of the surname.

† Every Russian has three names. A first name, a patronymic and a surname. The patronymic name is derived from the father’s first name. The usual form of address among adults is the first name and the patronymic.