Читать книгу Miss Confederation - Anne McDonald - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

ОглавлениеPrince Edward Island is always thought of as the birthplace of Confederation because the politicians of the day, including Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, met in Charlottetown to discuss the possibility of a political union of the colonies of British North America. Thoughts of union had been bandied about for years, but it was in Charlottetown that it looked like the idea would finally take hold.

That was in the late summer of 1864, and the weather, which would normally have turned cool by September first, was unseasonably warm. Not only was Prince Edward Island playing host to the politicians who had come to talk union, but, amazingly enough, the first circus in almost a generation had just arrived in Charlottetown. The Islanders, it turned out, including the PEI politicians, were more interested in the circus than in the negotiations to unite the colonies. You can’t blame them. The late summer was as lovely as summer can be in what’s come to be known as Canada’s Garden Province, and the circus was the highlight of the season.

I learned all this one unreasonably hot summer in Toronto when I was teaching an adult English as Another Language literacy class, with students from all over the world. On a whim one sleepy afternoon, all of us sweltering together in an old school without air conditioning, the class watched a video celebrating Canada’s 125th birthday. The video told the story of the PEI Father of Confederation William Pope being rowed out in a tiny boat to the steamship Queen Victoria to meet the men who had come from Canada to PEI to talk Confederation.

I was astonished. My father was from Prince Edward Island. As children, my sisters and I had gone almost every summer to visit my grandmother and aunts and uncles there. I love the Island, and I love history, and I’d never heard any of this before.

I knew I had found a story I wanted to write.

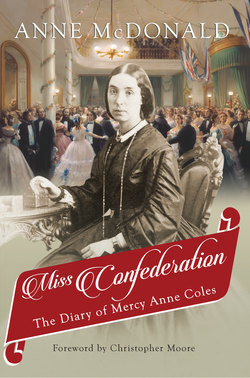

I began an enormous amount of research, and, in the course of doing so, I heard an interview on CBC Radio with Christopher Moore. He mentioned a young woman from PEI named Mercy Anne Coles. She had gone with her father, George Coles, to the Confederation conference in Quebec City in October 1864, which followed the summer meeting in Charlottetown. Mercy was one of nine unmarried daughters (only daughters went, no sons) of Maritime delegates who went to Quebec, where the now-famous Fathers of Confederation met to work out the terms for this union of all the British colonies.

And she’d kept a diary of her trip.

It was the Canadians, those from present-day Quebec and Ontario, who were most in need of a political union. At that conference in Quebec City they wanted to do everything in their power to charm the Maritime delegates. They must have realized it was crucial to keep the relaxed, convivial tone and lovely party atmosphere of Charlottetown going. And for that to happen, they knew they needed to include the women. Not only were the belles of Quebec City invited to the banquets and balls that were held alongside the political discussions, so too were the wives, sisters, and daughters of the Maritime delegates. In this way, the Canadians could court the Maritimers, and the Maritimers would be able to enjoy a sightseeing- and banquet-filled trip of a lifetime, at which their daughters could “come out.”

There are newspaper accounts of the events, banquets, and balls in Quebec City; speeches published months after the meetings; letters from George Brown (founder of the Globe, today’s Globe and Mail) to his wife; and limited minutes of the proceedings — all written by men. The story of the women who were present at the Confederation conference events has been absent from the record. Mercy Coles’s diary gives us that story.

I have transcribed the full diary, all of which is included in this book. Mercy’s two weeks of travel back home to PEI through the northern United States while the Civil War was in full swing, which has never been documented before now, is also included. This latter part of the diary was a revealing read; it captures a different side of Mercy, perhaps a more vulnerable side.

We are so lucky to have Mercy Coles’s diary. She thought to keep a record of the events, and just as importantly, she thought to preserve that record and pass it on to relatives. They, in turn, were wise enough to take care of it, and eventually share it with Library and Archives Canada.

It is the only full account of these events from a woman’s perspective. Further, it’s not tied to political ideals or machinations. It is a record caught at the moment history was being made, without the veneer or gloss that passing time creates.

When I first read the diary, I focused on the parts that were easy to read and transcribe, and used the events and timeline loosely in my novel To the Edge of the Sea, set during the Confederation conferences. It was a few years afterward that I began transcribing the full diary, reading it closely, paying attention to every nuance, and looking at the placement of words on the page.

Mercy was often travelling while she wrote — bumping along on the trains or in a carriage, and so, especially in the latter part of her diary, there are words and phrases that are illegible at points.

Because it is an original document, one can see Mercy’s style of writing and penmanship; they became an interest in and of themselves. I had to work closely with the text to understand what she was saying. For example, I wondered to whom she was referring when she wrote “Lala dined with us.… I was rather disappointed in the man.…” Whomever she was speaking of was obviously famous, but who was he? Not the yellow Teletubby, I was sure. A study of Mercy’s penmanship proved it was “Sala” I needed to look for, not “Lala.” Ah — it was George Augustus Sala, a British journalist, famous at the time, who was then travelling through Canada.

One can see how Mercy shapes her capital S, and R. The S is important to identifying Sala’s name. Her capital R is distinctive, closer to what is typically a small r, but made large enough to be a capital letter. The name Louis Riel comes out clearly, even though it is small in size, written to fit in the same line as “a Red River man,” but above it. It’s clear that the name was written some time afterward. How long afterward, though? It could very well have been later that same day. Still, the fact that it is an unknown time afterwards is important for assessing the accuracy of what Mercy knew at the time, and what she believed later. Even within this original document, then, it can be seen how the passing of time and the impulse of the author to edit her work have affected the history of the moment.

More than the study of the writing, though, it was the people, places, and events Mercy wrote of that interested me. At every turn, she piqued my curiosity. What were her relationships with John A. Macdonald or with Leonard Tilley? Why was the Victoria Bridge an important part of their sightseeing itinerary — and was that the same bridge we’d crossed over every week when I was a child to go visit my cousins in Montreal? Was diphtheria, which Mercy caught in Quebec City, really that bad? What was this “Bonnie Blue Flag” she wrote of while visiting with her relatives in Ohio?

I was intrigued by all she wrote. As I researched further, I felt like I was recreating a picture of Canada as it was at Confederation, a picture framed and circumscribed by what Mercy Coles presented to me, as it was presented to her. It is by no means a complete picture — it is, as I say, a circumscribed view of the time, the events, places, and people at an important time in Canada’s history. Importantly, Mercy has given immediacy, colour, and depth to all to which she turned her gaze, her female gaze.

That this is the first time the diary will have been published is extra-ordinary to me. Pieces of it have been quoted, but it has never been published in its entirety. That it hasn’t appeared until now speaks volumes about who and what we consider worthy of hearing. It is heartening that now, 150 years later, Mercy Coles’s writing will be available to all.