Читать книгу Miss Confederation - Anne McDonald - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Two

ОглавлениеCharlottetown: The Circus, Champagne, and Union

Thursday September 1, 1864, was a momentous day in Canadian history, the start to one long, sun-drenched, champagne- and circus-filled party.

On September 1, the Fathers of Confederation landed in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, to almost complete indifference, to talk about the possibility of a union of the British Provinces, or Confederation.

There was certainly political indifference, as it was the Canadians themselves who had wrangled an invite to a Maritime conference discussing a Maritime Union. The Maritimers weren’t interested in that union either, but were forced to consider the proposal by Arthur Gordon, the power-driven lieutenant-governor of New Brunswick. As Christopher Moore writes in 1867: How the Fathers Made a Deal, Gordon was “unshakeably certain that he was meant to rule New Brunswick as an Imperial potentate.” Gordon assumed he would have more power if the Maritime provinces united. He was definitely not interested in a union of all the British provinces.

There were many contentious issues in any discussion of Maritime Union: Where would the capital be? Who would head that government? How would issues of commerce, schools, shipping, or trade be decided, and by whom? All these questions and more made the Maritime politicians less than keen to join their three small provinces together, and so, in a brilliant effort to be free of any blame for what could develop from any union, or discussion of a union, the politicians and parties in power made sure to also include the Opposition. It was a bipartisan approach to a singular and significant event in Canada’s history, and the very bipartisan nature of the talks are what helped make Confederation successful. Moore attributes the initial bipartisan move to Charles Tupper. Delegates from all the political parties were invited to, and were part of, the Charlottetown conference. Further, the Canadians’ proposal for a union of all the British provinces was welcomed as a proposition that would sideline the issue of Maritime Union. This larger union would also, later, be viewed by the Maritimers as a way to extend their influence, and Maritime issues, beyond the narrow confines of their small provinces.

Prince Edward Island would not even have participated in the talks if they hadn’t been held on the Island. Living on an island, residents were self-sufficient. They didn’t feel they needed anyone else; indeed, they felt that they would only lose out in any federation, or larger union. They believed that such a union would deprive them of the fruits of what they had already accomplished for themselves. This stance is made clear in an editorial from the Islander, June 24, 1864, reprinted in the Charlottetown Guardian, June 30, 2014:

UNION OF THE COLONIES. In this Island, the newspapers generally have declared against it, and it is seldom that one meets, among our agriculturalists, a man who will listen to anything in favor of a proposition which would deprive the Colony of its existence as a separate Government.

“We are very well as we are,” say our farmers, “our public debt is nothing — it is not, in reality, equal to half a year’s revenue. The neighboring Provinces have created large public debts by building Railways, why should we agree to share their indebtedness, seeing that without doing so we enjoy all the advantages of their Railroads?”

Being the smallest province, and, of course, being separated from the mainland, made it likely that the Islanders were correct about how things would go for them. And it was the railway (its creation, and its debt) that eventually “drove” Prince Edward Island into Confederation — but not till 1873.

Still, as the noted PEI historian Francis Bolger points out, there was some positive talk of the idea of a federal union on Prince Edward Island, certainly more positive than that of a Maritime Union. Nevertheless, the interest was so lackadaisical that the lieutenant-governor of PEI, George Dundas, had to be spurred on by a sudden visit from the lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia, Richard MacDonnell, even to answer a telegram from Governor General Lord Charles Monck outlining the Canadian government’s request to make a presentation at the conference. And thus, finally, Charlottetown was chosen as the location for the conference, and September 1 was set as the date for its start.

In this sultry late summer, the Maritime delegates (minus Newfoundland, which was not included at this point) convened at Charlottetown to begin their talk of Maritime Union, and to wait for the Canadians — to hear from them about the more palatable idea of a federal union.

And why would the Maritimers be interested in a federal union? In brief, there was the possibility of an intercolonial railway, and the threat of the ongoing American Civil War. The colonies (all the colonies, both from the Maritimes and Canada) worried that the expansionist mood of the States might lead its government to pursue the annexing of Canada and the Maritimes.

Why the Canadians wanted Confederation is the subject of a whole other book, or many books. In short, Canada, known then as the “United Province of Canada,” which was made up of Canada East (now Quebec) and Canada West (now Ontario), was in the midst of an interminable power struggle. Each half of Canada had equal representation, an equal number of votes in Parliament, and the population and government of both sides often disagreed. The issues of Canada East — rural, French, and Catholic — were significantly different from the issues of Canada West — growing in number with its influx of immigration. The parties in power kept falling, and the United Province of Canada was at an impasse.*

The Macdonald-Taché government of Canada fell on June 14, 1864, defeated by just two votes. There had already been four elections in two years. The government was in deadlock. That’s when George Brown of the Reform Party offered to form a coalition with the Macdonald-Taché government, if they agreed to consider representation by population through a union of the British colonies — in other words, a confederation. Historian W.L. Morton described the reaction when John A. Macdonald announced the agreement in The Critical Years 1857–1853:

The House, wearied of piecemeal and sterile politics, wear-ied of a prolonged crisis, rose cheering, and leaders and backbenchers alike stumbled into the aisles and poured onto the floor. The leaders shook hands and clapped shoulders; with a spring the little Bleu member for Montcalm, Joseph Dufresne, embraced the tall Brown and hung from the neck of the embarrassed giant. The tension of years of frustration broke in the frantic rejoicing.

The Canadians were in far greater need of Confederation than the Maritimers, and they’d done everything in their power to get an invite to the Maritime conference. Macdonald had the governor general make the official request to the Maritimers. It was luck and coincidence that things lined up the way they did.

The other (and more exciting) cause of the indifference in Charlottetown to this historic conference was the presence of Slaymaker and Nichols’ Olympic Circus, the first circus to play on the Island in twenty years. People came from all over the colony, and even across the Northumberland Strait, from Shediac, New Brunswick, and beyond, to see the circus. The circus arrived Tuesday, August 30, and was leaving September 2. All the hotels, carriages, everything had been booked by the circus-goers, leaving the Canadians, the famous Fathers of Confederation — John A. Macdonald, George-Étienne Cartier, George Brown, D’Arcy McGee, and the others — to stay out on their ship, the Queen Victoria. They did have a hold full of champagne, mind you.

The lack of attention given to the arriving delegates was reported on disparagingly in all the newspapers. On September 2, the Islander commented this way:

Upon arriving in Charlottetown [at noon on Thursday, September 1], Honourable W.H. Pope, Colonial Secretary, met the Delegates, but no carriages were in waiting except for a few private ones belonging to friends of one or two of the delegates. The reason why the whole duty devolved upon Mr. Pope, I have been told, was that his colleagues in the Government were all attending the circus, the feats of horsemanship, the saying and doings of Goodwin’s clown … having greater attention for them than men of like pos-ition with themselves.

Of course, the Islander was owned by Pope himself, and so he is given credit, but this report was, in fact, true. William Pope was the only person from the PEI government to greet the Canadians, though the greeting was hardly very official-looking or formal. Because the whole town was at the circus, Pope had to have himself rowed out in a small bumboat — a boat that met arriving ships in the harbour to sell them local produce.

Pope had also gone to meet the New Brunswickers, who arrived along with Lieutenant-Governor Arthur Gordon on the Princess of Wales, at eleven o’clock the night before. Their rooms were at the Mansion House, while Gordon was the guest of George Dundas, PEI’s lieutenant-governor. The Nova Scotians had arrived earlier in the evening of Wednesday, August 31, but weren’t met. Pope reportedly found them and showed them to the Pavilion Hotel.

Under the heading “And Still They Come,” the Vindicator reported on Wednesday, September 7:

On Wednesday night [August 31] the Princess of Wales brought some 200 passengers from Shediac and Summerside.… The circus also drew a large number of persons from all parts of the Island into the City, which has never been so crowded, except during the visit of the Prince of Wales, in 1860.

And thus the party began and continued: circus, champagne, sun, and union together. George Dundas gave a dinner party that first evening for as many of the delegates as he could fit at his house. No doubt Arthur Gordon was in attendance. He left PEI soon after, probably peeved that the Canadians had taken the wind out of his desired Maritime Union sails.

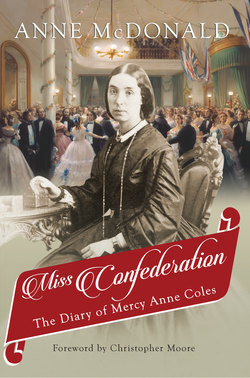

In the Guardian’s “Extract from a Diary,” Mercy Coles wrote:

The delegates from Quebec, Halifax, and Saint John arrived in Charlottetown on August 30, 1864 and held their first meeting in the Council Chamber. Dr. Tupper came to see us and said that a party of them had had an enjoyable ride and a shoot that was more amusing than profitable. This excursion, if not immortalized [was] at least commemorated by the Island Bard, the late John LePage.

This excerpt demonstrates the difficulty with the 1917 newspaper article. The dates are wrong, and because it is told as a summary of something that happened in the past, it loses the vividness of her original diary.

On Friday, September 2, William Pope gave a large luncheon in the late afternoon consisting of Prince Edward Island delicacies: oysters, lobster — and champagne, of course. The moon was full, and it was a beautiful night. Some of the Canadians went boating, other delegates took drives or walked in the evening air. George Brown wrote that he spent the evening on Pope’s balcony, “looking out at the sea in all its glory.”1

It was the Canadians’ turn on Saturday, and they gave a sumptuous luncheon on the Queen Victoria. The delegates ate and drank so much that the party continued until late in the evening. Brown wrote to his wife, Anne:

Cartier and I made eloquent speeches — of course — and whether as a result of our eloquence or of the goodness of our champagne, the ice became completely broken, the tongues of the delegates wagged merrily, and the banns of matrimony between all the provinces of B.N.A having been formally proclaimed and all manner of person duly warned then and there to speak or forever after to hold their tongues — no man appeared to forbid the banns and the union was thereupon formally completed and proclaimed!

The delegates were swept up in a new and optimistic nationalist mood. The party continued that evening at a dinner held by Premier John Hamilton Gray at his estate, Inkerman House. His daughters, Margaret and Florence, helped him host at the dinner, as their mother was ill. Margaret was one of the daughters who also went to the Quebec conference.** There was a short piece, titled “She Saw Canada Born,” in the Winnipeg Free Press on September 1, 1937, that told some of Margaret’s story in Quebec.

George Coles gave a grand luncheon at Stone Park Farm on Monday, September 5. Brown was taken by the Coles women: “At four we lunched at the residence of Mr. Coles, leader of the Parliamentary opposition. He is a brewer, farmer and distiller … and gave us a handsome set out. He has a number of handsome daughters, well educated, well informed and as sharp as needles.”2

On Tuesday, September 6, Edward Palmer gave the luncheon, and the lieutenant-governor and his wife gave a grand ball at Government House in the evening. On Wednesday, September 7, the Canadians hosted the lieutenant-governor and his wife, and the delegates and theirs, on the Queen Victoria. Mercy’s newspaper extract doesn’t include this event, though one imagines she must have attended.

Thursday was a holiday for the delegates — from the talks, at least, though not necessarily from the festivities — and they went on excursions into the country and to PEI’s warm north shore beaches. The evening held the final grand ball and banquet at Province House. There was dancing that started at ten o’clock in the assembly room, a bar and refreshments in the library, and a lavish dinner at one in the morning in the council chamber. And then the speeches began and went on for nearly three hours, even though the women were still part of the party. No doubt Mercy Coles came home very tired and “went immediately to bed,” as she wrote later of other, similar occasions.

This last event, the famous “Ball and Supper,” received a mishmash of odd comments in the press. Especially disparaging was the piece comparing the event to the circus.

The less-than-enthusiastic comments the Ball and Supper received after it was held matched the skeptical reception it had garnered beforehand. In the beginning, there had been such little interest in the Canadians’ arrival and their proposals for union that the tickets for this last big event hadn’t sold well. On September 15, Ross’s Weekly wrote, the Ball and Supper “numerically considered was a failure; the attendance would have been a skeleton one, had not the Executive, finding at the last hour … twenty tickets only had been sold [sent free invitations to Charlottetown’s elite].”

A week earlier, on the night of the banquet itself, the editor had complained how the government and its friends were attending the big ball for free, while “the citizens, Tom and Dick, and Pat, really and bonafide the givers of the Banquet and the Hop, [attended] at their own expense.” The Protestant newspaper lambasted the circus as evil, and another retorted back that it was the Ball and Supper at which evil showed itself.

Nevertheless, the Ball and Supper, in the end, was a success. The speeches went well, if long, and the partying and drinking had continued. The Canadians and the Maritimers went back to the Queen Victoria together at five o’clock, reportedly as befogged as the harbour. They were to head together to Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, but a thick mist had descended, and they waited till mid-morning to leave, no doubt a good thing for their “foggy” heads.

In contrast to the time in Prince Edward Island, with its unseasonably warm temperatures and sunny times, the conference at Quebec City involved lots of work, long hours, and incessant rain. There were still plenty of balls, dinners, and events to showcase the women; the Canadians wanted to show the Maritimers a good time in order to persuade them to join Confederation after all. The terrible weather, however, certainly affected the conference. The newspaper accounts talk of the endless rain; there was an early snowstorm when the Queen Victoria arrived with the rest of the Maritime delegates; and both the men and women fell sick and missed crucial discussions and the all-important events. Mercy Coles caught potentially deadly diphtheria.

* This is but a brief note on the why and how Union appealed to the people of 1864 — there is much more discussion of the topic in many history books and journals. Here, as our interest is in Mercy Coles, I am including but the briefest of notes for some context on Canada’s Confederation.

** Margaret Gray wrote diaries throughout her long life, and likely kept one for 1864, but it hasn’t been found. She lived to be ninety-six, and died in December 1941. The last diary in her collection is from 1937.