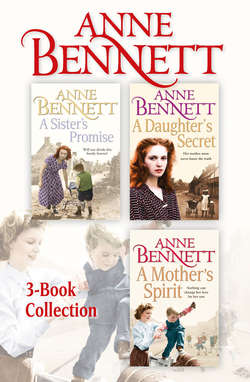

Читать книгу Anne Bennett 3-Book Collection: A Sister’s Promise, A Daughter’s Secret, A Mother’s Spirit - Anne Bennett - Страница 22

FIFTEEN

Оглавление‘Now are you sure you have everything?’ Tom whispered to Molly as she made ready to leave.

‘Everything,’ Molly said. ‘And there is no need for you to go with me.’

‘There is, and I would prefer it,’ Tom said, helping Molly through the window and following after her. ‘Anyway, I want to talk to you.’

‘Oh?’

‘Aye,’ Tom said. ‘Put your bag on your other shoulder and I will have your case, and we will walk arm in arm because it will be warmer, and I will tell you all about Aggie.’

‘Who’s Aggie?’ Molly said, glad enough to cuddle into Tom as they walked together through the raw, wintry night.

‘She was the eldest of the family.’

Molly wrinkled her brow. ‘Mom never mentioned a sister. In fact,’ she said surprised, ‘no one mentioned another girl. Did she die?’

‘I don’t know,’ Tom said. ‘I really don’t know what happened to her. She ran away from home when she was fifteen.’

Molly stopped dead and stared at her uncle. ‘Seriously?’ she asked. ‘She actually ran away from home?’

‘Yes,’ Tom said. ‘Your mother was only a year old at the time, and as we were forbidden to mention her name ever after it, she never even knew about her. That’s why, when your mother sent that letter to Mammy, it was probably like a double betrayal. Two daughters gone to the bad, as it were – not that that excuses her behaviour in any way.’

‘Did Aggie want to marry a Protestant too then?’

‘No,’ Tom said. ‘As far as I am aware she didn’t want to marry anyone.’

‘But … Uncle Tom, she was little more than a child,’ Molly said. ‘Where did she go and why?’

Tom shrugged his shoulders. ‘If she ever sent a letter to give any sort of explanation then I never saw it, or was told of it,’ he said.

‘Now,’ Molly commented, ‘why doesn’t that surprise me? But …’

‘Come on,’ Tom said. ‘We must walk before we stick to the ground altogether and it would never do for you to miss your train.’

Molly saw the sense of that, but her head was still teeming with questions about the unknown Aggie she had just found out about. She wondered why her grandmother hadn’t made enquiries of her whereabouts, get the Gardaí involved as Nellie had thought Biddy might if Molly had tried to leave before she was eighteen.

‘Did Aggie’s life with her mother just get that difficult?’

‘You could say that,’ Tom said gently. ‘Poor Aggie. As the eldest she had no childhood at all and was run off her feet in much the same way you were. Look,’ he went on, ‘though I can tell you nothing of what befell Aggie after she left here, and I was then only thirteen and not in a position to help her at all, that’s why I wanted it to be different for you.’

‘There is no comparison,’ Molly said. ‘I have a good case full of nice clothes and a money belt full of cash, even food for the journey, and that fine torch and a rake of extra batteries, as it will be dark by the time I reach Birmingham. Every eventuality is catered for and, look, I can see the lights of the station from here. You need come no further.’

But for all Molly’s brave words, Tom heard the quiver in her voice and knew she was perilously near to tears. For the first time, he put his arms around her and held her tight.

‘Don’t think the worst,’ he said. ‘Wait and see.’

‘It isn’t thinking the worst, Uncle Tom,’ Molly said, taking comfort from her uncle’s arms around her. ‘It is being realistic.’

Tom, who now knew Molly well, was aware she was very near breaking point, and though he could hardly blame her, it wouldn’t help for her to go to pieces now. He released her and said, ‘Come on now. You have to stay strong for young Kevin. If you are right – and I hope and pray that you are not – then how must he be feeling?’

Molly straightened her shoulders and wiped her eyes, for her uncle was right and if some second terrible tragedy meant that they were left alone in the world, then it was down to her, because she was eighteen, almost an adult, and old enough now to see to her brother. As soon as she reached Birmingham, she intended to seek him out.

Tom saw with relief that Molly had recovered herself and said, ‘You will write? Even if you have no permanent address for me to write back to, let me know you are all right. Nellie will hold any letters you send me?’

‘I will be glad to write to you,’ Molly said. She stood on tiptoe and kissed her uncle on the cheek. ‘Thank you for your kindness to me over the years.’

Tom’s face was flushed crimson with embarrassment and his voice gruff as he said, ‘Everything I did for you was a pleasure, and you may as well know that I will miss you greatly, more than I ever thought possible. But now you must go, for the train will not wait.’

Tom watched Molly walk away until the darkness swallowed her up. Burned into his memory was the day many years before when Aggie had climbed out of the window to make for England and to the very city that Molly was making for. From the night he’d watched her climb into the cart at the top of the lane, he never saw or heard from her again and he knew he wouldn’t rest until he got a letter from Molly saying she was all right.

Molly knew the train she would travel to Derry on would be a goods train really, but she would be comfortable enough in the passenger coach they attached to the end. When she booked her ticket, the stationmaster warned her the journey would be slow with plenty of stops, but this was the only convenient train. The other passenger trains didn’t go out until too late for Molly to catch the mail boat when it sailed with the tide at about ten to eight.

That early winter’s morning, Molly entered the carriage with a sigh. She could hardly credit that she was here at last, on her way to Birmingham, and on this date, Tuesday, 19 November, more that five years after she had left it. Had she just been going home in the normal way she would have been in a fever of excitement, but the nagging knot of worry about the safety of her loved ones had crystallised into real alarm at the arrival of Kevin’s note and she wished the journey was over and she was safe at the other end.

She stacked her case in the rack above her and sat back in the seat. Thanks to Nellie and Cathy’s generosity she was warmly and respectably clad for the journey. She had delighted in the feel of the soft underclothes against her skin and the brassiere that cupped her breasts so comfortably as she had dressed that morning, and she had chosen to wear the tartan skirt and the red jumper that Nellie and Cathy had insisted she had. The thick black stockings were her own, but the fine boots had once been Cathy’s and she smiled at her reflection in the mirror as she unplaited her hair and coiled it into a bun, which she fastened at the nape of her neck. It was the way Nellie wore her hair, and Molly knew that immediately she looked more grown up.

It was a shame she thought that she had to cover her fine clothes with the old black coat, which was as drab and shapeless as ever, though even that looked better when teamed with the tam-o’-shanter and scarf that Tom had bought her that first Christmas.

The journey was, as she had been warned, very stop and start, and so slow that sometimes she had an urge to get out and push. One half of her was in a fever of excitement to get to Birmingham, to find Kevin and bring him some measure of comfort, and yet the other half of her recoiled from the idea of what she might find.

By the time the train had chugged its way into Derry, she felt as cold as ice and burdened down with sadness. The night was still dark as pitch on the train to the docks at Belfast, and though the sky had lightened a little by the time she was aboard the boat, it hardly affected Molly’s mood.

The pearly dawn had just begun to steal across the sky when she stood on deck and watched the boat pull away from the shores of Ireland. She remembered doing the same thing in Liverpool when she vowed to return, and she also remembered the promise she had made to her little brother, which she was now going to keep.

This time, although her stomach did churn a little, she was able to eat and keep down some of the food that Tom had packed for her, and she bought a cup of nice hot tea to wash it down, but it didn’t chase away the cold, dead feeling inside her, nor stop her imagining the tragic and devastating scenario waiting for her at the end of the journey. Many spoke to the young and very pretty girl travelling alone and looking so sorrowful, and although she was pleasant enough, she wasn’t up to a long, in-depth conversation with anyone. She wanted to keep herself focused on what she had to do once she reached Birmingham, because that helped keep the tears at bay and she had shed quite enough of those.

Although the day was grey, overcast and bitterly cold, Molly was glad it was daylight when they reached Liverpool and she followed the other passengers as they made their way to the station. The train south had passed three stations with the names blacked out before she mentioned it to a fellow passenger.

‘It’s to confuse the enemy,’ the woman said. ‘You know, in case there are spies travelling about the country.’

‘But how do people manage if they didn’t know the area?’

‘Have to manage, and that’s that,’ the woman said. ‘I mean, my dear, don’t you know there is a war on? God, if I had had a pound every time someone said that to me since this whole shebang started, I would be a rich woman by now.’

‘Yeah,’ said another. ‘As if you couldn’t know. Even if a Martian landed I would say he would be aware of it, and in short order too. And the government treat us like imbeciles. I mean, look at that poster.’

The train had drawn to a halt at another nameless station and Molly saw that on the wall was a poster showing a man and woman standing beside a train ticket office that looked closed and the poster asked, ‘Is Your Journey Really Necessary?’

‘It’s because they want trains left to move the troops, my old man said,’ the first woman told Molly. ‘But I ask you, with this stop-start nature they have at the moment and the way trains never run on time, because “there is a war on”, you understand, if your journey wasn’t necessary, then I’m sure you would stop at home.’

‘This is all new to me,’ Molly said. ‘I was born in Birmingham but was taken to my grandmother’s in Ireland when my parents died five years ago.’

‘Ah,’ the first woman said, ‘how lucky to have one of your own willing to take you in, in such awful circumstances.’

If only you knew, Molly thought, but didn’t give voice to it.

‘Why come back now?’ asked the second woman.

Molly told them about her young brother staying with his grandfather and the absence of letters that prompted her to come and see for herself what had happened to them.

‘Well, I hope you find them both safe and sound,’ the first woman said. ‘But you will see Birmingham is very changed from the place you remember, and the two women regaled Molly with tales about the raids on Birmingham and the great swathes of the city laid waste, until the train drew up at a station they said was Crewe, where they had to change trains. Molly remembered it well, but for all that, was worried about missing Birmingham when she eventually got there. She was glad the two women were travelling on with her as they said they would make sure she got off at the right place.

They were true to their word, and when Molly alighted from the train, despite herself, she scanned the platform. She would have given anything to see her grandfather waiting for her, to see his eyes light up when he saw her, feel his arms go around her tight. She would smell the smoke from the pipe he always left in his jacket pocket, and she would kiss his dear, weathered cheek and tell him how glad she was to be back.

Tears stood out in her eyes at the realisation that she might never see him again, and she suddenly felt very lost and more than a little scared. She had no plan of action. She had money and knew she had to find lodgings, but she had no idea where to start. The almost sleepless night and the long and wearing day had begun to take their toll.

Two men had been watching Molly. They saw she was young and noted that there was no one to greet her. She was just the sort of girl they were interested in. Their eyes met, but they didn’t speak; there was no need. They waited until the platform virtually cleared of passengers and the girl still stood there in an agony of indecision, trying to batten down her rising panic and decide what to do first.

‘Can we be of any assistance to you, miss?’

Molly had no sense of alarm or unease, rather relief that someone had actually spoken to her, especially when the two men looked so respectable, dressed in suits and shirts and ties. The man who had spoken had actually doffed his hat, which had been a novel experience. Who better to ask advice of than these two men?

She had actually opened her mouth to say this, but she was prevented by the wails of the air-raid sirens and she looked at them, her eyes standing out in her head and intense fear displayed in every line of her body. Ray Morris, the man who had spoken to her, knew that he was on to a winner, for the girl was stunning, absolutely stunning, and he knew Vera would pay a good price for one who looked like this – when he had broken her in a bit, that was. She liked them broken in, did Vera.

But that was for later. Now there was the air raid to deal with, a raid that the girl was obviously scared rigid of. He took her arm, saying firmly, ‘Come, we must seek shelter. My name is Ray Morris and my friend here Charlie Johnson. Don’t worry, we will look after you.’

Molly was only too glad to let the two men take charge, and they led her from the station. Outside was a hive of ordered activity, for everyone seemed to know where they were going. Molly and her escorts followed the stream of people. The strains of the siren died away and the dull thumping sounds of the first explosions, as yet some way away, could be heard.

Powerful searchlights lit up the sky and men with tin hats on their heads and armbands circling their upper arms urged people to hurry. Molly was never so pleased with anything as she was at the feel of Ray’s arm through hers, while his friend Charlie came behind carrying the case. They went into a brick building, which seemed surrounded by sandbags. It was cold and dank, and very dim as the only light came from a couple of swinging paraffin lamps. The place looked very uncomfortable, the only seats bare wooden benches fastened to the walls. Yet Molly was glad that Ray sat her down on one of those, with him and Charlie beside her, because there wasn’t enough seating for all the people crowding into the place and some had to make themselves as comfortable as possible on the floor.

Molly had inadvertently arrived in Birmingham at the start of the worst raid that the city had suffered so far, though none was aware of that yet, of course. Inside the shelter, people talked and smoked and played cards, and some sang while others prayed. However, as the raid went on hour after hour, the crashes, bangs and booms becoming relentless, accompanied by the ringing of the bells of the emergency services, Molly wasn’t the only one giving small yelps of terror or shaking like a leaf. The heart-rending screams and cries from the frightened babies and small children rose above everything.

The air grew muggy and stale, and Molly wasn’t sure how long they had been entombed when just above them there was one terrific explosion. Even the seasoned Brummies, well used to raids, began to wail and whimper in fear. The wardens played their torches around the roof and walls and Molly saw that the walls were bulging in an alarming way, while the roof was creaking ominously. She suddenly felt her eyes gritty and tasted brick dust in her mouth, and by the light of the warden’s torch she saw the mortar seeding from between the bricks holding up the roof trickling down on those below.

Suddenly the shelter door was opened and a warden popped his head through. ‘Get everyone out,’ he cried, ‘and quick. This place is in danger of collapse.’

There was pandemonium and panic. People were shouting and shrieking as they fought to get out first, elbowing others out of the way. Ray, however, took hold of Molly’s arms and pushed his way through the fear-driven crowd until they were out on the street, where the air smelled of smoke and gas, and scarlet flames licked the night sky. It was no safer, of course, and the warden was trying to direct the distressed people to the nearest alternative shelter. Molly stood a little way from the sinking, collapsing shelter and saw nearby buildings that seemed to crumple to the ground in a mass of rubble and masonry. The tramlines were lifted and buckled, and there were great craters in the road.

Above, the planes were all around her like menacing black beetles, flying in formation, droning like thunder, and the barking of guns, which she presumed were trying to bring them down, was incessant. She actually saw the bomb doors of the first planes open, saw the black harbingers of death toppling from them before Ray took one arm and Charlie the other as they hurried her through the streets after the warden trying to lead them to a place of safety.

Molly noted with some surprise the devastation around her as they leaped over masonry that had spilled onto the pavements, and avoided potholes, dribbling hosepipes and bleeding sandbags. By the time they reached the nearest shelter, which was in a cellar, Molly felt rigid with fear and quite surprised that she was alive and in one piece. She felt she would always be grateful to Ray and Charlie because she knew she wouldn’t have managed half so well without them.

Throughout the rest of that raid, Molly trembled and shivered in abject fear, jumping with any louder than usual bangs, and she bit her bottom lip until she tasted blood. In the end Ray put his arms around her. In fact she snuggled in further, seeking comfort, and Ray held her shaking form and encouraged her to tell him what she was doing in Birmingham.

‘It might help,’ he said. ‘Take your mind off things.’

Ray had another reason for asking. Molly had all the hallmarks of a runaway – there had certainly been no one waiting for her with arms outstretched at the station – and yet there was something about that theory that didn’t quite gel. He had to be sure there would be no marauding father after him, no policeman feeling his collar.

‘I doubt there is anything that I can say or do that would take my mind off what is going on,’ Molly said, flinching at the noise of an eruption too close for comfort, ‘but I will tell you if you like.’ She intended to tell him a diluted version of what had happened to her, but Ray was too skilful at asking questions for her to do that unless she had been downright rude, and how could she be to someone who had been so kind to her? When she began it just spilled out of her, particularly the concern she had for her little brother and how important it was to find him as quickly as possible.

‘Don’t worry,’ Ray said. ‘I will help you do that, if you like. Though you were born and bred in Birmingham you were a child when you left it five years ago and the place is so different now.’

‘I think you are one of the kindest men I have ever met,’ Molly said sincerely. ‘And I thank God I met up with you this night. And I would be grateful for any help you can give me.’

Ray smiled to himself, but he had noticed the slur in Molly’s voice and how her eyes were glazed with fatigue. He said, ‘You look all in, if you don’t mind me saying so. Why don’t you lie against me and try to sleep?’

Molly didn’t argue. She was very tired, though she doubted she would sleep, but it was a relief just to lean against Ray and close her heavy eyes, and quite soon afterwards the exhausting events of that very long day overcame her and she fell into a deep sleep, despite the noise of the continued bombardment.

Ray, watching her sleep, told himself he was on to a winner this time. This Molly had no mother, nor father either, in fact no one but a young boy to miss her at all. It was just perfect, especially when he found out where the boy was and ensured that he wouldn’t pose any sort of problem to them.

Molly was woken with a jerk by another ear-splitting siren and, seeing her alarm, Ray gave her shoulder a squeeze. ‘That’s the all clear, sweetheart,’ he told her. ‘It’s all over, at least till the next time.’

Molly hadn’t been the only one who had fallen asleep. Around her, others were waking stiff and cold, and began making their way to the door. Molly felt sorry for the mothers trying to rouse still drowsy children, or soothing fractious ones while they gathered their belongings around them.

And then, she suddenly realised, apart from the bag that she had hung from her shoulder, she had nothing with her at all. After a cursory look around she said, ‘Where’s my case?’

Though it had always been part of the plan to dispose of the case, like they always did, Charlie looked contrite. ‘I’m sorry, Molly. When they told us to get out of that shelter and fast, the case just went out of my head.’

Molly could quite see how that would be. She had been frightened witless herself, but everything she owned was in that case. ‘It’s all right,’ she said. ‘Really, I do understand, it’s just …’

‘We’ll go back that way,’ Ray promised, ‘and see if we can salvage anything, if you like, but just now I could murder a bacon sandwich.’

‘So could I,’ Molly said. ‘But where will you get one of those?’

‘WVS van,’ Ray said. ‘Course, they don’t always have bacon, but toast and tea would fill a corner, I bet.’

‘You bet right. Lead me to it,’ Molly said.

She found it just as Ray said. Only a street away was a van where two motherly, smiling women dispensed sympathy and humour with the tea. They were doing quite a trade, both with the weary homeless and the rescue workers. The orange sky lit up the early morning like daylight and Molly could see that almost all were covered with a film of dust, on their faces and in their hair. She guessed she was the same, and that her hat was probably ingrained with the stuff. They did have bacon butties, quite the nicest Molly had ever tasted, and these were washed down with hot, sweet tea. After, Molly, who had been feeling quite frightened and tearful, was more in control.

That was until she surveyed the mound that had been where they had taken shelter earlier that night and knew she would have been killed if they hadn’t got out. What was her life in comparison to a caseful of clothes? Nothing, of course, but what was she to wear – and in fact where was she to sleep off what was left of the night?

Ray surveyed the mound with satisfaction, knowing the case would be crushed beyond recognition. And he knew the site would remain untouched: there wasn’t the manpower to clear mounds of rubbish that were no danger to anyone. It was all they could do to rescue those trapped, and so this time Ray didn’t even have the bother of throwing the case in the cut, like he’d had to do a couple of times.

He said to Molly, ‘So, what are your plans now?’

‘I haven’t any,’ Molly said. ‘Not now, I mean. I had intended looking for lodgings just for a few days while I found out a few things and, I hoped, located Kevin, but then there was the raid and all, and now I don’t really know.’

‘Well, you can’t go looking for lodgings at this time of night – or morning, I should say,’ Ray said, ‘because it isn’t yet five o’clock.’

‘I know,’ Molly said. ‘Maybe I should go to the police station. They could probably direct me to a rescue centre, or something.’

That was the very last thing Ray wanted her to do, but he showed no alarm. Instead, he draped an arm around Molly’s shoulder and said softly, ‘Look, around you, Molly. This sea of rubble used to be streets and streets of houses, and the people that once lived in them are filling the rescue centres. They are bursting at the seams. The raid you witnessed tonight was one of many. The city has been pounded since August.’

‘What, then?’ Molly asked helplessly.

‘Well,’ Ray said, ‘I am looking after a flat for a friend who can’t live in it at the moment. It’s the first floor of a house not far away and the place is completely empty. It would be somewhere to lay your head down for tonight, at least.’

How Molly longed to do just that, but maybe it wasn’t wise – not that the men had said or done anything remotely suggestive or improper, and Ray in particular had been kindness itself.

‘Neither of us has designs on you, so don’t think that,’ Ray said, and he spoke the truth for he was not attracted to women, men and boys being more his scene. And as for Charlie, though he would sample both, he liked his woman older, far more experienced and willing to indulge in fairly kinky sex. Girls like Molly did not interest him in the slightest.

When Ray said, ‘We won’t even be there; we both have our own places,’ the last of Molly’s reservations fled.

‘All right then,’ she said. ‘I would like to have the use of the flat for tonight at least.’

The house Ray took her to was on the end of a terraced row, and next to it was a wide entry bordered on the other side by a high wall that had once been part of a factory, until it had been decimated by the bombing. The house had been converted into two flats very skilfully, and both were completely self-contained.

Beyond the front door, stairs led to the flat on the first floor while the door underneath the stairs led to the groundfloor flat. In the flat itself, just inside the door, was a hallway. Charlie helped Molly off with her coat, and she took off her dusty hat and scarf too. As she pulled her money belt over her head, she said, ‘I had all my money in there. I was advised that it was the safest way to carry it.’

‘Quite right too,’ Ray said, putting it in the drawer of the cupboard next to the coat stand. ‘There are all sorts of strange people about today. Come on in and see the place.’

Molly was amazed when she saw the opulence of the flat, which even the blackout curtains couldn’t entirely spoil. The floor of the very large living room was carpeted and lit with two glittering chandeliers. And if that wasn’t luxurious enough, two maroon settees and an armchair, which Molly was sure were leather, were grouped around the gas fire with a shining brass fender. Two bureaus of dark wood were in the chimney alcoves, on top of one a fancy wireless, which it bore little resemblance to the one Tom had bought in Buncrana. Against the far wall was a shining, dark wooden dining table, and tucked beneath it were six chairs, again upholstered in maroon leather. And the whole place was heated by radiators.

‘It is absolutely marvellous,’ Molly said. ‘But, Ray, won’t your friend mind me just moving in like this?’

‘No, Molly, he’ll be pleased,’ Ray said. ‘And that is the honest truth. You wouldn’t know the way your old city is now. Empty properties are either occupied by squatters, who have been bombed out, or commandeered by the military. My friend has only got away with it so far because this is on the first floor. Anyway, it’s only for a few days.’

‘Yes, that’s right,’ Molly said. ‘He must have a fine job, this friend of yours.’

‘I wouldn’t know what he does,’ Ray said vaguely. ‘A bit of this and a bit of that.’

Molly thought it a funny sort of job, but she reminded herself that he was Ray’s friend and it really was none of her business. She contented herself with exploring the rest of the flat. There were two doors from the living room. One led to a sparkling kitchen that Molly knew it would be a pleasure to work in. At the other side of the room a door opened on to a small corridor with two further doors leading off that. The first was a bathroom and it had all manner of beauty products left there: body creams and lotions, even some cosmetics, as well as shampoos and soaps such as Molly had never seen in her life before. She wondered at the manner of woman, for it must have been a woman, who would leave all this behind, as if she had left in one hell of a hurry.

She shrugged. That wasn’t her problem and she was more than glad the things were available when she caught sight of herself, for her face was coated with dust and dirt, which was even gilding her eyelashes. Feeling a little daring, she filled the basin with water, which was piping hot, washed her hands and face with the delicious-smelling soap and dried them with the soft, fluffy towels left behind the door. Then she tidied her hair with the comb that she found in the little glass-fronted cabinet on the wall.

Feeling better and more refreshed, she went from there to the bedroom. The bed was very large and she noted the sheets were silk. The fact that they were black with cream edging was unnerving enough, but what really threw her were the mirrors on the ceiling and down the length of one wall. Then she knew that however lavish this place was, she would breath easier when she was away from it.

Back in the main room, the men had opened a bottle of brandy that they said they had found in the cabinet part of the bureau and they had a glass filled for her too, diluted with lemonade. There was something else added to Molly’s glass, which would make her sleep like the dead, for Ray said he didn’t want to come back and find the bird had flown, though he would take the precaution of locking the door.

Molly’s heart sank. She was incredibly tired and would have preferred to seek her bed, even with the black silk sheets, but she knew Ray and Charlie only meant to be kind.

‘I have never tasted alcohol,’ she said, lifting the glass and sniffing apprehensively.

‘Bout time you did then,’ Charlie said. ‘What age are you, anyway? Sixteen? Seventeen?’

‘I was eighteen in February,’ Molly said.

‘Then the brandy will do you no harm at all, and once you have it drunk you will sleep like a top.’

‘I think I would sleep well enough without the brandy.’

‘It’ll be better with, trust me,’ Charlie said. ‘Isn’t that right, Ray?’

‘It’s right,’ Ray said. ‘And when you have it drunk then we will leave you to sleep the sleep of the just. So let us toast the fact that we met up with you tonight.’

Oh, Molly had no trouble toasting that. She didn’t dare think of what might have happened to her if she hadn’t met up with these lovely men. ‘Down the hatch,’ Charlie said as the glasses chinked. Molly took a large swallow and found she liked the taste, and accepted another when she found her glass empty.

But when she had finished that one, she felt very peculiar. She knew Ray and Charlie were talking, but she wasn’t able to register what they were saying. Her head had begun to swim quite alarmingly and when she tried to speak, her voice was befuddled and she couldn’t remember what she had wanted to say.

‘I would say you are a wee bit drunk,’ Ray said with a smile.

Molly tried to say she was sorry but her tongue seemed to have swollen to twice its normal size and what came out was just gobbledegook. Ray and Charlie laughed.

‘Come on,’ Ray said. ‘We’ll help you to bed and be on our way.’

Molly tried to say she didn’t need help, but she was unable to form the words, and when she tried to stand, she found she couldn’t do that either. It was as if her legs belonged to someone else. The two men carried her to the bedroom and laid her on the bed, where her eyes closed of their own volition.

‘What are you doing?’ Charlie asked as Ray began easing Molly’s jumper up.

‘Undressing her.’

‘But, why?’

‘Well, I don’t want to leave her in her clothes all night,’ Ray said. ‘She won’t remember any of this. If we were that way inclined, we could both take her now and she’d be none the wiser. But she is more valuable to us as she is because I am positive she is a virgin and I have Collingsworth looking for just such a girl. He is willing to pay and pay well if the girl is untouched.’

‘So what are we doing this for?’

‘Because when she wakes tomorrow under the sheets and in a slinky nightdress, and we say we left her fully clothed, she won’t remember a thing about it and I have a feeling that will unnerve her a bit and that’s what I want.’

Charlie shrugged. ‘You are a queer kettle of fish, mate,’ he said. ‘But I won’t argue with you because I think we are sitting on a little goldmine with this one, if we play our cards right.’

‘That is what I am counting on,’ Ray said. ‘So you just look in those drawers and get me the slinkiest, sexiest nightdress you can find.’

And Charlie, with a grin, did just that.