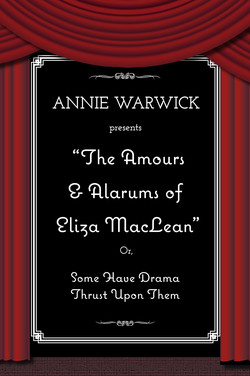

Читать книгу The Amours & Alarums of Eliza MacLean - Annie Warwick - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 1 ~ An Unusual Alliance

ОглавлениеIn which we introduce the early years of an unusual alliance between Eliza MacLean and Billy Sylvester, and Eliza knows the many joys of being an actor’s daughter.

“Begone, foul brat,” said Billy, but there was a certain fond amusement in his voice. “Duck,” he advised her, and pushed the window completely open, in contradiction to his previous instruction. Eliza climbed in, her face pink with the exercise of cycling, scaling the convenient Quercus robur growing outside in the street, and lowering herself onto the porch roof which allowed access to her Prince’s Chambers. Both tree and roof could be treacherous, so her feet were bare for this last part of her pilgrimage, with shoes being tied by the laces and strung around her neck.

At this stage, in the early 1990s, Eliza would have been seven or so, and Billy five or six years older, depending on time of year. She knew he often retired to his bedroom after dinner on the pretext of studying, but really to avoid the washing up.

The Regal Bedstead of her Prince seemed like a good place to recoup her energies for the trip home, so she threw herself onto it. Billy rolled his eyes, shook his head and lay down on the other side of the bed, holding his book with a contrived air of long suffering while she tried to take it out of his hands, prattling on all the while.

“I’m reading The Lord of the Rings,” Eliza announced.

“Uh huh,” said Billy. “How do you like it?”

“It’s hard, but I like it,” she told him.

“Who will you be?” he asked her.

Eliza tried out roles in her imagination. “I should be a hobbit, because I’m a midget, or an orc would be fun.” She pulled an evil face and snarled at Billy. “But I’d really like to be Galadriel. Would you be Aragorn? Or Gandalf?”

“Saruman!” said Billy, without hesitation.

“Ooh, yes,” she said. Then, “Billy, Galadriel is pretty. Do you think I’ll be pretty when I’m older?”

“Nah,” he said. “Hideous!”

She looked at him with her deep blue eyes opened wide and head tilted in an enquiry, to see if he was serious, so he took pity on her. He ruffled her curls and smiled at her sweet little face, already pretty. “I think you’ll be very pretty, now go home!” He opened his book again and she was effectively dismissed.

Eliza was satisfied at that, and didn’t push her luck. Somehow she knew where the line was drawn. She disappeared out of the window, and went home the way she had come, without a thought about safety. Her father, had he known, would have been very angry with her.

And he was angry, some time later, when Billy’s concerned mother phoned him to report having apprehended a monkey, apparently belonging to him, in its attempt to gain access to the upper levels. It spent several minutes disputing with her the logic of coming down and entering the front door like a civilised human being, when it would be quicker, at this stage, to go in the window. More economical of energy, as it were. The little tree-dweller’s points were cogent and well-argued, but eventually it gave up and dropped to the pavement. Billy’s mother ushered the monkey, still chattering its protest, in the front door. Since she needed to maintain her authority, she turned her face away so it didn’t notice she was trying not to laugh.

In those days, Eliza’s father was absolutely self-absorbed and knew little about raising a child in the 1990s. When she went to bed, he assumed she would stay there. Sometimes, though, when it was still light, she would pull on some clothes over her pyjamas, put on her shoes, walk quietly out of the house, and jump on her bicycle. Legs pumping furiously, she would cross the dangerous roads – where trolls lurked under bridges – separating her father’s spacious Victorian dwelling from the modest terraced house where Billy lived with his family.

No threats of trolls, in fact, or the bogeyman, had ever been used to control her, and she had no fear of being kidnapped and murdered, an obvious oversight on her father’s part. Yet with the grace of some benevolent deity who regularly looks after small children, among others, she managed consistently to avoid all fast-moving vehicles, paedophiles and serial killers, and she got to see her Prince for a few minutes.

* * *

Eliza and Billy met when she was six and he was twelve. An unlikely match, at least for commoners in the twentieth century. He wandered past her front gate after school was out, late as usual and on his way home by a circuitous route that involved a park and an open-air theatre. She, already home, changed and ready for her make-believe world, was dressed in a pirate hat, with eye patch, and holding an overlarge cutlass. Despite his slouch and the sullen manifestation of youthful self-consciousness, she thought he was the most beautiful boy she had ever seen. He was tall and lanky, with a broad forehead, dark hair and hazel eyes which seemed too large for his pale face. He didn’t notice her at all, of course.

After that, she made sure she was in the garden at the same time every day, waiting to see her Prince. She made no attempt to engage him in conversation. Even at six, she knew that boys, especially boys so old and worldly, were not about to compromise their social standing by being seen talking to six year olds. So she just looked at him solemnly and invisibly.

One day he emerged from his thoughts for long enough to register that the garden gnome in the front yard of number thirty-one was actually a small girl. He looked at her with only as much curiosity as was seemly in one so above it all. She might have been the poster child for the Moppet Club. Her hair was almost black, and curly. She was quite pale, except for her pink cheeks and the cherry lips of a young child. Her eyes were almost too big, and almost too blue. She looked like everybody’s favourite dolly; she would probably, if tipped backwards, say “Ma-Ma”, and she was dressed incongruously in a pirate hat and eye patch.

“Arrrr,” she said, as befitted a pirate of her standing, as desperate and bloodthirsty a villain as one could hope to see in Primrose Hill on a sunny autumn afternoon. He looked back, and a smile started, reluctantly, at the left side of his mouth. Eventually, in spite of itself, the smile made it all the way across.

“Arrrr,” he returned, and continued on his way, still smiling.

* * *

Victoria Eliza Annie MacLean had rather an unusual childhood, although she had nothing with which to compare it, and therefore could find no fault. Katharine Adelaide Mary MacLean, younger by three years, was the second and last of Richard and Lisette MacLean’s daughters. British queenly names are quite thin on the ground and repetitive, so it’s perhaps as well they stopped at two. One feels that things would not have gone well in the schoolyard for little Boadicea MacLean.

On a day which rather stood out in Eliza’s memories, some months after her third birthday, her nursery-school teacher, Kirsten, drove her home as a favour to her father, and left her at the door after ringing the bell. Kirsten rushed back down the garden path and drove away at speed, as though pursued by a canine of menacing aspect and pointed teeth. The door was already open, so Eliza ran down the wide hallway and into the kitchen, whence the usual baby noise was coming, to find her baby sister, her father and her aunt hovering over a tin of formula and a bottle. Kathy, her face red from screaming, was being held and jiggled by Auntie Danni, a study in Stoicism, while Eliza’s daddy did an excellent job of Agitation, running his hands through his hair. This told Eliza he was not going to want to hear about how she had bitten little Rufus Jacobson, hard, on the elbow. Eliza considered it fair retribution for scribbling on her drawing, but realised this was not the time to present her case. She pulled her aunt’s sleeve, and whispered, “Auntie Danni, where’s Mummy?”

Her father became aware of her presence at that point, and picked her up, kissed her and tried to act all cheerful. He did a woeful job, for an actor. “Mummy’s had to go away for a rest, darling. She isn’t well.”

“Is she going to die?” asked Eliza, with interest, not really knowing what it meant to die, but then she suddenly remembered being told that Daddy’s grandfather had died. She knew he had gone away and she had not seen him again. Then Daddy had been hurt in an accident while he was out in the car. Daddy had come home from hospital after a couple of days, but she had not seen the car again, so it must have died. Suddenly Eliza felt terribly scared.

“Daddy,” she said, her mouth turning down and her eyes filling. “Is Mummy coming back?”

“Yes, poppet,” he told her, relaxing a little now because the baby, with her mouth full of milk, had stopped screaming. “Auntie Danni’s here to help us with Kathy.” He sat down with Eliza on his lap and cuddled her, possibly more for his comfort than hers.

Nobody really knew, for the moment, if Mummy was coming back. It seemed that after a few months of trying to manage her husband, her wilful elder daughter, and a baby, Lisette MacLean had a bit of a breakdown. By that, I mean she cried a lot, stayed in bed a lot, and generally sent out a distress call that was picked up by Her Majesty’s Coastguard, Thames, but nobody came to help. People probably told her to pull her socks up. She wasn’t wearing any because the washing hadn’t been done for two weeks. The only thing that occurred to her was to run away and leave both children with her husband, Richard.

That night, after a bath, another feed, and the singing of many lullabies by Auntie Danni, Kathy went to sleep, and thankfully slept right through the night. Eliza, however, did not. She kept getting up to check on the grownups in the lounge room, and on her sister. She eventually got into her aunt’s bed with her, and Danielle was too tired to argue.

At about three o’clock the next afternoon, Eliza, having refused to go to nursery school, announced loudly from her window seat sentry post, “It’s Mummy, she’s back. Daddy, she’s home.”

“Thank god,” muttered Richard, and rushed to the door to seize his wife in a crushing embrace, meant to convey that he could not do without her and please don’t go away again. Lisette kissed him and held him, telling him she was sorry. She kissed Eliza and the baby, then she and Richard went up to the bedroom for a while, to talk. Danielle shook her head, and sat at the kitchen table to write a list of instructions, entitled “How to look after a baby”. She had a feeling it was going to be needed in the near future.

A week later there was a lot of shouting coming from the study. Eliza sat with Kathy, shutting the door and singing some songs she had learned at nursery school. A great fear started to build in her tiny three-year-old body, and she could hardly sing for it, but being the eldest she had to look after her sister. Luckily she couldn’t hear what her parents were saying.

“I’ll take the downstairs bedroom and you can just move her in! It would save her phoning and hanging up all the time. It’ll be no trouble for her to take Eliza to school with her. We’ll all be winners!” Lisette was behaving in a way that always made Richard uncomfortable, since in his family peccadilloes were considered to be just that, and not mentioned at home. “And by the way, you’re shitting in Eliza’s nest,” she added.

“I’m sorry,” said Richard, automatically. “She’s just a fan. You know how these women get. I’ll talk to her and tell her to stop.”

“If you’d stop sleeping with them, maybe they wouldn’t get the way they do!”

And much more along the same lines.

Then Lisette ran away again. A few days later, she returned, collected the baby, and left for good. Richard MacLean, able to understand and express on stage and screen any feeling you care to name, was a Grade A moron in the emotion department when it came to his wife. Neither of them knew anything about post-natal depression or why living with a handsome, brilliant, temperamental, faithless actor would cause a woman to go off the deep end after the birth of her second child.

“I really am at a total loss,” confessed a heavy-eyed Richard to Kirsten, who looked as though she had recently finished her A levels, but in fact had reached the advanced age of twenty-four. He’d just had another traumatic evening trying to get Eliza to go to sleep, or even to stay in bed. He wasn’t a cruel father, but he was tired, so he tried yelling at her. She immediately curled herself into a tight ball on the floor in the corner of the drawing room and closed her eyes, apparently asleep. “She won’t go to bed, she won’t stay with a baby-sitter or go with my sister. She never used to be like that.”

Richard ran his hands through his hair. “When she finally goes to sleep in a chair and I take her upstairs, I’ll wake up in the morning with her in my bed.” A couple of nights ago, Richard had put Eliza to bed and locked his bedroom door, which took a lot of resolve because he was a bit of a softy. In the morning he found her stretched across the doorway, sound asleep, and he felt like an absolute monster, of course.

Richard loved his little daughter, but the poor sod had absolutely no idea what was going on. Put simply, Eliza, at three, had lost her mother and her baby sister, and was acting out, something fierce. Anybody, well, almost anybody, could see she was refusing to go to bed in case her only remaining caretaker disappeared in the night like the rest of the family.

“Get her a pet,” Kirsten advised him, with the simplistic wisdom of the young. “Cats are good,” she continued. “They’re self-cleaning and they bury their droppings.” Richard, in a state of advanced sleep-deprivation, had no fight left in him, and so decided to shop for a moggie on the following day. He obtained, from the veterinarian’s clinic, an ordinary female tabby cat, about seven or eight months old, nothing unusual except for her large, round, brilliant green eyes. They called her Mehitabel and she slept with Eliza, followed her around, and allowed her all manner of familiarity which she wouldn’t tolerate from anyone else. Calling her for dinner was a tongue-twister, so sometimes they just yelled “Belly-Belly-Belly!” And gradually Eliza adjusted.

Victoria (when a serious talking-to was imminent) Eliza (the default condition) Annie (when she was good) visited her mother and sister at preordained intervals and was told to be on her best behaviour. At such times Kathy pulled Eliza’s hair and scribbled on her books. Such behaviour during reciprocal visits met with instant and painful consequences, as nature intends. Eventually, though, the visits became less regulated and hence more tolerable.

* * *

Although this story isn’t about the supernatural, both father and daughter had the look of the Sidhe, with that unearthly beauty which can both fascinate and repel, causing the suggestible to believe that faerie kind and humans can and do mate, producing offspring that are unholy and probably dangerous. Eliza was independent, argumentative, slim, and dark-haired, like her father. Unfair though it was, and as much as he tried to hide it, Richard preferred her to her softer, more compliant sister. Eliza knew her father loved her but there was no doubt that his preoccupation lay with other matters at times, principally his work, and his love life.

Richard wasn’t averse to monogamy, unless he was married, so he only had one woman at a time, changing partners once or twice a year. Apparently the Post-it note stuck to each of their foreheads showed the use-by date clearly enough. Due to the turnover, there was no point in Eliza’s regarding them as potential mother figures. In any case, they were mostly in his bedroom or in the kitchen fixing a snack and wearing either her father’s shirt or the Emperor’s New Clothes. Apparently having a man walking around naked in front of his own little daughter could be grounds for summoning a social worker, but having his girlfriends flashing the gifts God gave them was no problem. Eliza was quite blasé about the naked human female form after all this.1

1 She was curious to see her father naked, just for completion, however he obstinately remained fully clothed at all times in her company, so she was forced to ask some of her little classmates to show her their willies. This got her into trouble of course.

In the fullness of time, Kirsten went the way of the others. She did not take it well and, eventually, with great reluctance, Richard took Eliza out of the nice, friendly, new-age nursery school where some of his friends in the profession took their children. Her new nursery school had a fee structure which assured the desired exclusivity, and consistent progression all the way through her school years. Eliza, however, was distressed at the premature change, and Richard realised, to some extent anyway, what Lisette had meant about shitting in Eliza’s nest. He made a mental note never again to seduce a woman, no matter how comely, involved in his daughter’s education.

Eliza grew up with the firm belief that, mostly, if you wanted anything done you had to do it yourself. This included buying clothes and school books, and putting dressings on wounds. On one occasion, she phoned a taxi to take her to hospital to have her broken arm set, returning home, while the hospital staff had their backs turned, in time to feed the cat. Mehitabel was a constant in these times of continually shifting role models and thankfully she came from a line of long-lived felines with good road sense.

* * *

It was sometime in February, 1989, and Eliza was about to turn five. She had a mulish look on her face, one that Richard recognised only too well.

“No, I won’t,” she said emphatically.

“Why not?” asked Richard. “You’re always acting. I’ve seen you as a pirate, a princess, a vampire. I think you’d be good at it. Why don’t we get you some lessons, and you can learn to do it properly as part of your schoolwork.”

“I don’t want to,” she said, uncertainly, not wanting to disappoint her father. She didn’t know why she felt so strongly about it. Maybe she had already overdosed on theatre, having spent days and evenings sitting with the other theatre orphans, wrapped in blankets against the cold, while their parents rehearsed. Whatever her motivation, she remained adamant that she would not be following in his footsteps and treading any kind of boards. If she had been a little older, even by a couple of years, she may have told him what she already felt, but didn’t yet have the words for: I want to be normal. I want to be myself.

So he yielded with bad grace, and therefore, because some kind of performance skills were mandatory for a MacLean, he insisted that she learn no fewer than two musical instruments and undergo vocal training. Regular practice, if Eliza was recalcitrant, was enforced on pain of being shouted at, vis-à-vis, in a terrifyingly loud and resonant voice designed to reach the back stalls. Richard excused this example of harsh parenting on the grounds that projecting his voice was instinctive because of his calling2 and averred he had no intention of terrifying small children.

2 “Acting is the art of speaking in a loud clear voice and the avoidance of bumping into the furniture.” – Alfred Lunt.

She had long since got over her tendency, when shouted at, to curl up in a ball in the nearest corner. At four or five she started standing her ground and shouting back at him. From seven on she just folded her hands and waited for him to finish. One could almost believe she had decided not to reinforce bad behaviour with attention. Much later, she ignored him or shouted back as the occasion demanded, and neither of them thought very much of the altercations.

Eliza had already demanded to learn the violin at the age of four. She chose the tin whistle as her second instrument, which was, as he informed her, pushing it. Fortunately she sang beautifully, and little work was required aside from turning down the volume knob on the high notes to preserve the glassware and any passing eardrums.

Richard appeared to have a considerable private income, over and above what he earned in his profession. He didn’t come from old family and old money, but nonetheless he grew up with the belief that he didn’t have to impress anybody, and so felt free to live in whatever manner he chose. His house had been in the family for generations, one of many such pieces of real estate, and he didn’t bother much with the décor or home maintenance, unless something was leaking or about to explode. Being a celebrity in theatrical circles ensured that people thought he was merely charmingly eccentric.

So at least Eliza didn’t have to raise herself in poverty. Someone came in to clean the house, do the washing, and cook five meals a week. A modicum of domestic competence was expected of Eliza, and she was tested in these skills from time to time, although she was probably far too young to be put in charge of a roasting pan and a gas oven. Baking was more fun than cleaning the bathroom, or peeling veg, she decided, and playing culinary jokes on her father, like making Chelsea buns for dinner, appealed to her sense of humour.

Richard required that school work must be completed with high grades, but otherwise Eliza’s time, what remained of it, was her own.

Although this is not Kathy’s story, it is predictable that she eventually pursued an acting and dancing career. No sibling rivalry was needed here as, well into her twenties, Eliza regularly fell over nothing on non-slip floors, using this deficit to further substantiate her claim that acting was an unsuitable career for people like her.3 Interestingly, she had no trouble climbing trees or keeping her balance on a roof.

3 See note 2 above on bumping into furniture.

Because this is Eliza’s story, it is also Richard’s, and lest it be thought that he was an uncaring father, let us be clear now that nothing could be further from the truth. He absolutely adored Eliza, and let her know it frequently, but when, shortly after his thirty-first birthday, he assumed full care of her, he was still young, in the way some men tend to be when they have been surrounded by admiring women all their lives. Unless hit on the head with some evidence of his parental neglect, he assumed everything was going well.

* * *

Billy You wouldn’t do old Hook in now, would you, lad? I’ll go away forever. I’ll do anything you say.

Eliza Well, all right, if you say you’re a codfish.

Billy I’m a codfish.

Eliza Louder!

Billy (screaming) I’m a codfish!

Eliza Hook is a codfish! Hook is a codfish!

Billy tries to stab Eliza with his school ruler, but she dodges and he falls into the sea (a.k.a. the grass). Eliza changes roles and becomes the crocodile. She snaps at his heels as he swims away frantically.

Eliza Tick tock tick tock tick tock …

Billy Nooooooooo!

* * *

Billy did not appear to regard Eliza as a nuisance, in fact he apparently sought out her company at times, which puzzled both Richard and Billy’s parents. She came into his life at an awkward and painful age, when he did not have many friends to whom he could relate, and none who understood his obsessive drive to act. Perhaps he saw in Eliza a kindred spirit, hopping the fence after school and playing Captain Hook to her Peter Pan. She in turn would help him with his lines in the school play by reading the other parts, which also improved her reading skills. Eliza was always glad to see him and never told him lies, even if the truth hurt, thus she was his earliest and most honest critic as well as his most admiring fan.

When the student is ready, the teacher appears. At about the time Eliza and Billy first exchanged Arrrs, Richard, who loved to teach acting almost as much as the acting itself, was involved in Saturday drama classes for young people. Billy eventually joined the class on Richard’s suggestion. He had noticed a certain raw talent in Billy, perhaps seeing himself at a similar age, and decided to encourage him. At that stage, Richard became the drawcard for Billy: a male role model who didn’t expect him to go into the family business or ridicule him for his theatrical penchant.

Billy took correction and impatience from Richard which would have had him spitting tacks at his father and slamming out of the house. He tried it once, but Richard merely said, to his departing, huffy back, “Do you want to act or not?”

Billy stopped on his way to the door. After a pause, he turned, and said, “Yes”, which was accompanied by a few remaining un-spat tacks.

“Then you will need to take your critiques with your accolades,” said Richard. “Don’t ever do that again!” he added, a touch of irritation in his voice. Billy was hot tempered, but he could always change direction if the map suggested he was going to drive into a gully.

Inevitably, Billy gradually became absorbed into the MacLean household. Richard was happy to have another source of Eliza-sitting at his disposal and Billy was quietly pleased to be associated with this guru of the dramatic arts. A certain stitched-up atmosphere prevailed at Billy’s home, and the unconventional MacLeans made him feel unrestricted and more aware of his own dreams and potential. His aura at home would have been a tealight, at the MacLeans, a candelabra.

* * *

The friendship which had developed between Eliza and Billy ended when she and Richard moved to Australia for a year in 1994. He was appearing in a TV series as a handsome but sinister doctor, providing himself with extra income and intellectual stimulation by teaching Voice to the next generation of teenage soapie stars. Eliza was just ten, attending a private girls’ school in one of Sydney’s leafy suburbs, and finding no shortage of invitations to attend parties and sleepovers. This puzzled her since, although friendly and entertaining when in the mood, she was quite at home in her own company and did not seek out friends. She investigated this unusual phenomenon.

“Angie, why did you invite me to your sleepover? I’m pretty sure you don’t like me that much.” Later on Eliza would fine-tune her social skills but for now she was just being honest.

“No, you’re right. I don’t like you at all, actually.” Now here was a girl who didn’t have any trouble with expressing the truth as she saw it.

“So … ?”

“My mother has a king-size crush on your father.”

“What! Did she pay you a fee? Why can’t she just dance naked on our front lawn or something? He’d probably take her in, he’s not that fussy.” Eliza was mortified and it manifested itself in sarcasm.

Angie gasped in outrage. Slaps and punches ensued. There was flying fur, hissing and growling, hair pulled, shins kicked, foul language, all to the excited cheering of onlookers. Eliza, who would probably never have given up even if she was bleeding from the ears, was later deemed by a panel of gladiatorial spectators to have won because Angie started crying. Cue arrival of outraged duty mistress. Attendance at principal’s office, detention in separate rooms. Note to parents.

Just to ensure her research was accurate, Eliza asked one of the other girls but modified her approach, taking the above experience into account. “Kyra, did you invite me to your birthday party because someone in your family has a crush on my father?”

“Yeah, sorry. Don’t hit me!”

“That’s okay. Happens all the time.” Eliza patted the girl on the shoulder. Kyra and Eliza became friends after that, although they both agreed they would keep it secret from Kyra’s oldest sister.

It occurred to Eliza that she had very few friends who apparently liked her for herself. It was all a bit depressing, because although she didn’t crave approval, she had grown up expecting it. Really, Richard could have put her on her guard about this, as he had been the object of female adoration for over twenty years. From Richard’s point of view, Eliza’s absence at a sleepover merely represented an opportunity for him to pursue his amours.

The Note came home. “What the bloody hell is this?” was Richard’s initial response, since his daughter’s school reports had never before been sullied by anything as crass as a cat-fight.

“Girls have been inviting me for sleepovers because their mothers have a crush on you,” said Eliza, who felt it was time he took some responsibility. “And sisters,” she added, pedantically. “I got angry.” She told him what Angie said, and what she said, and what happened. “Dad, I want to be normal,” she added, with emphasis.

Richard’s Anger immediately looked abashed and tried to hide under a chair, as he began to remember his sister having similar complaints when they were at school. Even then, Richard’s saturnine good looks and air of smouldering sexuality caused schoolgirl hearts to beat faster. Their schools were segregated, of course, but there were brothers and sisters attending each school, and it didn’t take much: family attendance at school recitals, or a school play in which Richard would, of course, be appearing. Danielle, only fifteen months younger and in the year below him, was inundated with invitations and overtures of best-friendship as a ploy to get to know him.

Danielle loved her brother, but once he started to make a name for himself, she never admitted to their relationship and would deny it most elegantly if questioned. “I wish!” she would say, as convincingly as one would expect of a MacLean. “But no, he’s no relation. I expect there’re lots of MacLeans in the phone book!” Fortunately for Danielle, she took after her mother in appearance, however Eliza’s resemblance to her father was so striking that denial was futile.

“Sorry, poppet,” Richard apologised belatedly. “I had no idea females could be so manipulative.” He smiled at her a little ruefully. “What should we do if we find school mums dancing naked on the lawn?”

“Hose ’em down?” suggested Eliza, much entertained by the possibility.

Eliza felt that females were often unreliable and usually hard to fathom, except for Mehitabel. At present she didn’t even have Mehitabel, who had been sent off, under protest, to live with Auntie Danni in the Cotswolds.