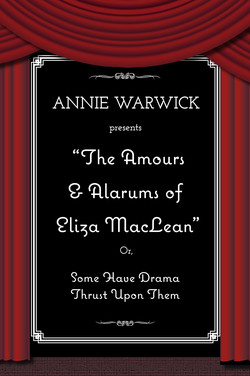

Читать книгу The Amours & Alarums of Eliza MacLean - Annie Warwick - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 4 ~ Transportation

ОглавлениеFeaturing some reminiscences on Richard’s lovers, Billy’s pointy ears, a new musical focus, a large feline, and a really satisfying charade.

Eliza had a lot to not think about, and it was straining all her not-thinking-about-things resources. She had a number of strategies which had served her well in the past. For instance:

Play violin.

Play tin whistle.

Write music (although when one was sad, the music did tend to be somewhat doloroso).

Sing Ne me quitte pas in the shower while sobbing intermittently (useful if the sad feeling refused to be avoided).

Read a book.

Write a book (the drawback was that it tended to be about the sad thing one was trying to avoid, resulting in sobbing intermittently at one’s own tragic narrative).

Watch TV.

Exercise madly to exhaustion.

Indulge in auto eroticism.

Buy clothes and boots.

Bake.

The fact was, though, she was sitting in the right-hand side of a 747, at the moment in the window seat, and, although there was a large expanse of ocean beneath her, she was not in a position to allow its depths to enfold her in a final, chill embrace. She was surrounded by people, particularly her father, and not all of her strategies for avoiding her feelings were available. She had read as many books as she cared to and the inflight movies were the sort of thing which, really, provided no competition to the alternative of cutting your own throat. If she could just sleep away the trip, perhaps arriving in Sydney would then be distraction enough.

She did surreptitiously cross her legs, trying to get an orgasm going, very very quietly, but it was more to see if she could do it than a response to an urge. Eliza had been most impressed by a woman seen recently on a TV documentary who could induce an orgasm just by contracting her vaginal muscles. At any rate, Eliza’s faint, rhythmic movement must have attracted Richard’s attention, and he brought his book down sharply on her leg.

“God, you must be bored! Do that again and I swear I will take you to the vet.” He opened the book again with a snap and a flourish, and continued reading. Eliza subsided in a sulk; although not believing Richard for a minute, she wondered if that was the answer. Perhaps she could get herself desexed, because as sure as hell her libido was causing her nothing but anguish.

If she had no libido, she would not have these continual images of kissing Billy, touching Billy, and she wouldn’t be feeling a sinking, dragging sensation like all the goodness was draining out of her, leaving her like a shrivelled piece of beef jerky. Had Richard decided to go back to Australia to keep her out of mischief? Surely not! Mischief was readily available in Australia, she was certain. For the first time, she felt she was leaving important things behind in London. Even her mother and sister – whom she saw only occasionally, and who often annoyed the bejesus out of her – represented a stable base of connectedness.

The thought of leaving her cat was, for some reason, almost as bad as leaving Billy. Richard referred to Mehitabel as her familiar, but Eliza knew she was her own furry soulmate, who had been with her since she was three, and now, in her twilight years, she was being left behind. She must be thinking that nobody wanted her, which was a horrible thing to happen. Actually Mehitabel, with feline ESP, had taken herself off to the Sylvesters’ house about six weeks previously, and had slept on Billy’s bed since then, occasionally visiting Eliza if she wanted some extra food or cuddles. Had Mehitabel sensed that Eliza was going away and wanted to avoid Auntie Danni’s place? Did she regard Billy as part of her Pride and therefore an obvious alternative source of food, affection and shelter? Cats’ minds are difficult to read, even for an Omniscient Narrator, but think about the last time you tried to get away with packing to go on holidays, prior to scooping up the cat and taking it to the boarding kennels. Did not said cat, despite your attempts to pretend it was an ordinary sort of day with nothing going on, glare suspiciously at you and hide in next door’s potting shed?

Eliza gave a sniff accompanied by a tiny, tiny whimper, so eloquent in its wretchedness that Richard abandoned his book and put his arm around her. She leaned into his shoulder and sniffed a little more, with some satisfaction at being cuddled. Eventually she went to sleep and was gently resettled into the corner of her seat, with a pillow behind her. The sense of absolute dejection would have wrung the withers of a more callous man than Richard. But she’s young, she’ll get over it, he told himself, though doubtfully.

Richard remembered the angst of being young and in love. He had a sudden masochistic urge to be beaten to a pulp by love again. It’s a sweet kind of pain, he thought, when you get a bit of perspective, but from the inside, my god, the depths, the heights, the sheer unmitigated mindless passion.

* * *

Richard could remember being really in love only three times in his life. The first love was the sort of grand passion in which young men of artistic temperament are particularly adept at losing themselves.

In the mid-1970s, Richard had lived in a huge Victorian house in Hampstead with his family, the whole shebang: his parents, himself, his sister, and both sets of grandparents. They were obscenely well-off, although he’d been discouraged from enquiring too closely into the origins of this wealth.

His grandfather had entertained many well-dressed visitors in those days. They patronised the arts with great gusto, his early stage performances being attended by the sort of people who would take you outside and give you a talking to if you didn’t applaud their favourite actor with sufficient enthusiasm. Ah well, it’s a cut-throat business!

He was nineteen, and reading English at Oxford. Naturally, coming from a family whose money was thought to derive from having, in the past, been somewhat Vigorously in Business in the East End, his background was discreetly held against him in certain quarters. Having been warned by his father of what to expect, Richard was able to use this experience to build extra layers upon an already thick hide. Money did not really compensate for his inherited chequered background, however it served to augment his natural advantages – outstanding intellect, sporting ability, good looks and charming arrogance – ensuring that he found his niche, even at Oxford in the seventies.

He was learning and practising his craft however he could, and made as many trips to Stratford-Upon-Avon as he could manage. However, in this case it was not for the theatre itself but because he had an insane crush on a Shakespearean actress who was thirty and married to a doctor, or was it a lawyer? He couldn’t remember. He only knew she was brilliant, beautiful, Junoesque. She was a goddess.

* * *

It was October 1975 and Miranda, a.k.a. Maureen Erskine, was sitting at her mirror in a tiny dressing room in a tiny theatre, preparing to remove the makeup which she had applied with a trowel earlier in the evening. “Oh for heaven’s sake!” she said tersely, as someone knocked on the door. She had already warded off a cluster of admirers and was not in the mood to be admired any more tonight. “Please God,” she said to herself, though not a devout woman, “let it be an Adonis, with wit and intelligence. Let him have black hair and blue eyes. Let him be over six feet tall and under thirty years old.” And she invited the knock to come in, so it did. The knock was the embodiment of her prayers, and held a single rose, apricot-coloured in homage to her titian hair.

He looked at her for a long moment. The smile hovering on his lips was pretending out of politeness to be uncertain.

“Hello,” she said, in a way that suggested she was not displeased to see him.

He did not speak, but held out the rose, thoughtfully de-thorned and tastefully bound with a ribbon, and he smiled, properly this time. I feel it is entirely possible that a group of concerned parents had, at some stage, considered taking out a court injunction prohibiting him from smiling within fifty yards of their daughters. Maureen, certainly, was not immune to that smile, and found herself wondering if it was time she had a toy boy, only the phrase wouldn’t be coined for another decade or so.

“Let me find you a chair,” she said, and went to rise, but he shook his head and very gently kept her in her seat, his hand on her bare shoulder and his long fingers, without any perceptible movement on her skin, seeming to caress her.

Richard:

No, precious creature;

I had rather crack my sinews, break my back,

Than you should such dishonour undergo,

While I sit lazy by.

Maureen:

It would become me

As well as it does you: and I should do it

With much more ease; for my good will is to it—

She stopped at that point and rolled her eyes, because the last line didn’t fit. They both laughed as Richard procured his own chair and placed it close to hers. “What brings you here to my dressing room, Ferdinand?” asked Maureen, wondering at the power of prayer.

Richard:

Admired Miranda!

Indeed the top of admiration! Worth

What’s dearest to the world! Full many a lady

I have eyed with best regard and many a time

The harmony of their tongues hath into bondage

Brought my too diligent ear: for several virtues

Have I liked several women; never any

With so fun soul, but some defect in her

Did quarrel with the noblest grace she ow’d

And put it to the foil: but you, O you,

So perfect and so peerless, are created

Of every creature’s best!

Richard delivered his lines without slip or omission, and Maureen was thus landed, with barely a resisting wriggle on the hook. Now she knew where she had obtained the vision for her prayer: Richard had attended several of her performances and the theatre was quite intimate, so it was difficult to miss him. She turned back to her mirror, and they talked while she scoured off her makeup, revealing the flawless complexion of a natural redhead who avoids sunshine and fresh air. She looked very young and vulnerable without it, and as she glanced at his reflection she caught an expression she recognised, that of the besotted and lustful male. Her scouring complete, and before her courage failed her, she turned around, stood up and kissed him gently on the lips to advise him of her intentions, which, as she well knew, were also his.

Because her husband was away at a conference, she took him to her bed that very night and they enjoyed a year of insane passion before her spouse, who was obviously somewhat slow on the uptake, became suspicious. Neither Maureen nor Richard was very good at keeping things uncomplicated, and they were absolutely obsessed with each other. He begged her to run away with him, a lad of twenty still to make his fortune, and with remarkable speed the illusion of a future together was dispelled by grim reality, which, as we know, has no sense of the romantic. Maureen was fond of her husband, and particularly of the lifestyle he provided, which enabled her to live in luxury, work when she wished, and not have to count her small change.

When Maureen ended the relationship, Richard was certain he would have to kill himself. He chose the ideal place to jump into the Thames, and stood there night after night, trying to get up the courage to carry out his dramatic statement.

In the end, sanity reasserted itself, aided by a harrowing dream. In this dream, he observed himself lying on a slab in a nineteenth-century morgue, with water dripping over his white corpse. The persistent drop drop drop of the water dislodged a huge chunk of his face which slid off the bones1 even as Maureen bent over him, mourning his death. She screamed and ran out, vomiting in the street.

1 The dream may have been inspired by Émile Zola’s Thérèse Raquin, which Richard had been reading at the time. It is perhaps fortunate that his relationship with Maureen ended when it did, before Richard was inspired to tip her husband into the Thames.

On waking, Richard realised Maureen was not going to turn up at the morgue sobbing hysterically over his beautiful corpse. If he was found, he was likely to be water-logged, disgusting, and probably smelly. Or fish would have nibbled his nose. No, this was not going to be a heart-wrenchingly tragic final act, it would be farcical.

He let the curtain fall on his personal melodrama, but he always had a slight penchant for red hair and voluptuous figures. He never saw her again, so his memories remained unsullied by reality. To see her grown middle-aged and fat, with the tideline of grey growing at the roots of hennaed tresses, would have been too much to bear.

* * *

Richard’s thoughts turned to Lisette. His ex-wife and Eliza’s mother. She was beautiful and feisty. He had loved her passionately, of course; he didn’t know any other way to do it. Their relationship had been fraught with partings and reconciliations right from the beginning, usually as a consequence of his bad behaviour. We all know the strangely compelling nature of Make Up Sex, and their relationship was full of it. He’d always started out, after each rift, with the best of intentions, but in the end it seemed that she had just burned out. Love had changed, not even to hatred but to a kind of exhausted resignation. They loved each other even when it was all over, but they could never be friends, except as a performance, for the sake of the children. He loved her still, but she had remarried, someone as far from the performing arts as she could manage, someone safe and unexciting.

* * *

The third love, which was less a grand passion and more like real love, was Linda. She was an artist and sculptor whom he met when she was twenty-eight and he was thirty-six. He was quite successful as an actor by that stage, but he enjoyed teaching. Fate, that unashamed Romantic, arranged it all: Richard would be plying his trade in the vicinity of the studio in which Linda was teaching artists to paint scenery for the theatre, and he would see her and pursue her. Actually she saw him first but he took the bait nicely. Her hair was indeed red, though closer to auburn. She had a well-proportioned hourglass figure, slender in build, but the way she walked was definitely voluptuous.

For a year they had a love affair which was both torrid and tender. He taught her everything Maureen had taught him; she taught him a few things of her own. She told him about her ex-husband’s affair with a monosynaptic twenty-year-old beautician. He told her about his marriage, his children, even his indiscretions, and she had a few of her own to relate. There are always secrets in any relationship, but theirs was surprisingly open and honest.

Linda, aside from her obvious attributes, was talented, highly intelligent, well read, and had a fine sense of humour, so they also talked and laughed. Richard was completely stripped of all pretence, of anything remotely inauthentic, in her presence. There is, after all, no real need for an actor to keep on acting when he removes the greasepaint.

She painted his portrait and sculpted his head, his hands and any other bits of him which took her fancy. Linda felt it was bad for Eliza to see her father entertaining women and having to meet them at the breakfast table, so although she sometimes insisted on taking Eliza with them on family outings, Eliza rarely saw her otherwise. She appeared, on the surface, to have no impact on Eliza’s life, however Richard mellowed under her influence.

Their affair ended when Richard left for Australia for a year, and lo! she refused to abandon a well-paid and exciting job offer to go with him. So they had a fight to justify parting and enable blaming, each of the other, which numbed the pain with anger.

When he returned to England he found she had treacherously married her boss. He later heard rumour of an affair followed by a divorce, but he did not seek her out, telling himself that if they had got back together the same problems would have occurred, his job or hers, England or Australia. In reality he couldn’t stand the pain of losing her again and he wasn’t going to risk it. The thing about hiding in your cave – aside from the hygiene problems posed by bat droppings – is that although nothing bad happens, nothing wonderful happens either.

* * *

“Dad,” said a very sleepy voice. “What’s the time? Where are we?”

“Are we there yet?” mocked Richard. “Not yet, my love. Do you need sustenance, some tasty airline cardboard food perhaps, or a cup of coffee-flavoured radiator water?” Eliza sat up and rubbed her eyes. She felt somewhat better and was definitely hungry and thirsty.

“We’re in business class,” she reminded him. “It can’t be that bad. Although if you weren’t so tight, we could fly first class, Scrooge MacLean!”

The trolley was trundling by, which probably woke her, and whatever it was Richard had ordered, it tasted pretty darned okay to Eliza. Richard, not to be deterred, muttered “pigeon or cat? pigeon or cat?” under his breath, as the trolley approached, but was charming to the flight attendants and they all wanted to sleep with him by the time he had finished making them feel special and attractive. Actors! thought Eliza, watching her father at work, but she was impressed anyway and couldn’t help smiling.

Even the most arduous flight eventually lands, with a bit of luck before you develop deep vein thrombosis of the buttocks, and so they touched down at Sydney’s international terminal, feeling decidedly unwashed and stiff, to start their next new life. For the first time, both of them felt they wanted to settle down and grow deep roots, absorb the nutrients of the culture, and make friends.

* * *

It was about this time that Billy stepped up the action on his career. Tired of working in shops and cafes or being a labourer for his father, he found himself a decent agent and set about promoting himself. He was still finishing his degree in the performing arts, and had a good network of contacts from the academy and community theatre. He took anything that was offered, a tiny bit part or an extra. Not always the sort of stuff you would want to put on the CV, but useful experience. Billy, by now, had grown some excellent social skills. He was a really nice person to talk to, and he was pleasant to everyone, whether they were acting, producing, or cleaning the toilets. You could have a normal conversation with Billy and forget he was one of the cast. He never complained, was always co-operative. Most importantly, he was good at his job, and people started remembering him.

A part came up for an episode of a popular supernatural-themed series, A Tale for Midnight – probably an updated version of the old Thriller. He was chosen to play a prince of the faerie kingdom who, instead of sticking to his own kind, had a predilection for seducing mortal women. The trouble was, he could never find one who didn’t die on him, because of the strain of living in the faerie realm, bonking a faerie prince and so on. They all tended to just fade away. Damn, the prince would think, tossing away the remains of the latest shrivelled lover, back to the drawing board. The husband of his most recent victim decided to thwart him in his wicked plan, but the prince refused to give up the wench, and of course ended up being vanquished with a choice selection of herbs and spices.

Mailbags of fan mail arrived for the mortal-loving faerie prince, because we all know girls love the bad boys,2 especially if they are hot.

2 It’s true. You can deny it all you like. We women are quite tragic, really, in that respect.

The first time Billy realised what had happened to him, he was wandering along South Molton Street, hoping to improve his sartorial image with a few purchases, when three girls bailed him up.

“Billy, Billy,” they said breathlessly, in unison. “It is you, isn’t it?” one of them said, uncertain because he seemed genuinely unaware, for a moment, of why three young females would be clustering around him. Then he got it!

“Well, my name is Billy,” he said, giving the prettiest one his best bedroom eyes, as he signed a piece of paper with his much-practised autograph: Billy Sylvester, with lots of love … “To?” he enquired, pen poised.

“Melinda,” she told him, and promptly reached up and kissed him on the cheek. The other girls crowded around and got their autographs and kisses, too. They wanted to talk about his faerie character, and seemed disposed to scoop him up and take him home with them, but he made his excuses. It occurred to him that he could possibly have taken all three of them to a hotel and got comprehensively laid. It seemed like an ignoble thought, so he pushed it away, but the idea made him smile on and off for the rest of the day.

All the girls wanted Billy’s character to kidnap them and have his wicked way with them. The producers of the show must have been kicking themselves for killing him off, because of the potential for a spinoff series, or at least another episode with the character. So Billy was on his way, and he was able to put Eliza in her Eliza box, on her Eliza shelf, along with all the letters he wrote to her and never mailed. After all, she had never written. It’s hard to pine over a lost book when there’s a whole library available.

* * *

Eliza had just showered and come downstairs in her PJs, planning to sit and watch a bit of telly with Richard and his girlfriend, whichever one she was, before getting an early night. She was a couple of weeks off sixteen, and had just started Year Twelve.

While still in England she had been put up a grade, apparently as punishment for getting into mischief. She had been caught doing her mathematics homework in French class, and when the teacher had smugly demanded that Eliza tell her, in French, what they had learned so far today, she was able to do so, fluently. It was the additional information, sotto voce, about the teacher’s resemblance to a farmyard animal, which had earned her a detention – and the grade promotion. Apparently Eliza had been doing the work standing on her head with both hands tied behind her back, and finding it boring.

With this experience behind her, when Eliza started school in Sydney she kept a low profile, but still they had given her extra work in order to get her prepared to move up to Year Twelve the following year. This was rationalised by the excellence of her marks, the fact that her birthday was early in the year – so she was really barely more than a year ahead – and her extremely mature social skills. So next year, she would be starting her Bachelor of Psychology, which was a four-year professional degree. She would be, technically, two years younger than most of her colleagues, but she had been absorbing psychology since she was twelve, the poor sick child, so the work was unlikely to be a problem. She felt a little like a science experiment, and told Richard she was thinking of changing her name to Doogie Howser, however he failed to grasp the cultural reference. She also resented having the slack taken out of the system, because she was fond of her limited leisure time.

On this day, as she prepared to use this leisure time in front of the television, Richard called out to her. “Eliza, quickly. Come and see who’s on the telly.” She padded into the room and sat down. For a moment, it didn’t sink in that the evil, yet curiously attractive, pointy-eared faerie prince was, in fact, her Prince. She had been at such pains to put him in his Billy box, on his Billy shelf, and yet here he was, looking absolutely gorgeous, and quite unearthly. And so unlike himself because if you really analysed his features, he was not the pretty-boy movie star type. This was his stock in trade, of course, being able not only to act a part convincingly, but somehow to change his face to fit the character, so he was hardly recognisable. She had watched him over the years playing a school dork, a bully boy, a pompous twit and even, once, an old lady, and his face fitted itself into each role, like a shape shifter, so she shouldn’t have been surprised.

“He’s good,” said Richard. “He’s very good.” Eliza watched the show without a word, though she would have preferred to run away, play something difficult on her violin and forget about it. He was her Billy and now he was on the telly for all to see. She knew she had lost him because they never wrote to each other, but this made it all the more ridiculous that she should be pining over him, along with probably half the teenage girls in England, and now Australia. So she put him back in his Billy box, now tightly Scotch-taped, on his Billy shelf, along with the letters she had written to him but never mailed. After all, he had never written to her.

She went off to bed without comment, and Richard shook his head. That girl needs some distraction, he thought. A rather wicked plan presented itself to him, and he dismissed it hurriedly, before anybody saw it and arrested it for loitering. The thing was, she was nearly sixteen, and had not had a boyfriend since coming to Sydney. She brushed admirers away like so many flies, and was obviously in love with her violin and her books. For a fairly neglectful father, Richard was somewhat interfering where Eliza was concerned, and his idea kept nudging at him. Because he was not constrained by the inconvenience of middle-class morals, he saw no problems, only the benefits, of encouraging a liaison between Eliza and a young friend of his.

Teague Atherton was twenty-nine, an actor of course, being one of Richard’s friends, and married for the last three years to Annicke, a lively and pretty television journalist who was away quite a bit chasing the news. Teague loved his wife but he was both missing her and chafing at the fidelity clause, which Richard well knew. When he and Eliza were first introduced, in passing, she was carrying the ubiquitous violin and rushing out of the house, but she recognised an attractive male when she saw one. She gave him a dazzling smile to fix his interest until she could get back and make discreet enquiries. He stared after her in blatant admiration, his mouth falling open a little. Richard raised an eyebrow, but he obviously had to exert an effort not to smile in amusement.

“Sorry,” said Teague, snapping his mouth to attention. “Your daughter. Very bad form to drool.”

“She’s not quite sixteen,” said Richard pointedly, but enjoying having the fruit of his loins admired so wholeheartedly.

Teague looked a little crestfallen at that. “She seems older; I guess in civvies and makeup they all look older. I would have guessed about twenty, even.”

“She’s very grown up for her age, in some respects,” said Richard, carefully. What was he thinking?! But then he had never treated her as a child, so why start now?

“No shortage of suitors, I imagine,” said Teague, equally carefully.

“She had a boyfriend in London, and hasn’t been socialising much since. She needs to meet someone to make her forget about the other one.” He did not qualify his statement to exclude Teague, but let it settle as it was.

It can’t be said that Teague immediately twirled an imaginary moustache or raised his eyebrows repeatedly while smiling lecherously to himself, but an idea did start to germinate at that point. Young girls were not his preferred fare: they were cute, with their hardly-used faces, but usually boring and often irritating. This one, based on a few words of conversation and the humorous look of understanding in her eyes, seemed different.

Who was Richard pimping anyway, his daughter or his friend?

It can’t be said that Richard offered his daughter to Teague. It can’t be said that he actively encouraged a relationship between them. He simply invited Teague for dinner with him, his own girlfriend, and Eliza. Then he sat back and waited.

The dining room lighting was subdued, and the food and wine excellent. Richard knew how to cook when he chose to. Eliza, because she knew Teague was coming to dinner, decided to wear something feminine, and almost completely failed to look like a schoolgirl of not yet sixteen. The short, lacy vintage top made it appear that an occasional glimpse of cleavage was entirely accidental, while the flowing skirt emphasised her slim waistline. Her jeans, tee-shirts and boots were abandoned in her wardrobe, there no doubt to sulk and plot revenge.

Eliza was well trained in dinner talk, and had a wide range of topics with which she was comfortable, but that night she was conscious of an odd distance between herself and her own conversation, as evidently a different part of her brain had other ideas.

“So, Eliza,” said Teague, “Obviously you play the violin, but I’m wondering what sort of music you prefer to play.”

Eliza didn’t want to talk about her violin, for some reason. “Just the usual,” she said, brushing the topic aside. “Orchestral. A bunch of fiddlers, fiddling away with smoke coming out of their instruments.” Her eyes were on Teague’s chest, but not because she was shy. She pulled her gaze back to his eyes with some effort. “But don’t worry, the blood from our fingers usually puts the fire out. Do you play an instrument?” she added politely.

“Classical guitar, or at least I try,” said Teague modestly. “We could play duets, and reduce the smoke if you like.” Eliza smiled at that. Richard noticed neither of them was eating much.

As the evening and the spirituous liquor progressed, everyone relaxed. Eliza and Teague didn’t notice that Richard and his girlfriend had retired to the kitchen to make coffee, or that this exercise was taking an unusually long time. Eliza had taken her shoes off and was curled up on her end of the couch, talking with Teague about books, music, psychology. She even made a concession and talked about theatre and acting, occasionally poking him with her foot to emphasise a point.

He appreciated her somewhat cynical philosophy, her sense of humour, and her shattering straightforwardness. And, of course, her physical attractiveness, which she took for granted. She would have hated to lose it but otherwise she did not pay it much attention. When we describe someone, we might say that they are like this person or that, but there was no-one to whom you could point and say, that’s the type Eliza is. Her face still had a little puppy fat to obscure what was excellent bone structure, and she was likely to improve with age for that reason. Her smile, when she chose to use it, was charming, but it was her eyes – the same curious dark blue as her father’s – and her colouring that caught people’s attention.

Teague was attractive, well built, medium height, which suited Eliza’s five-two nicely. She had planned to grow, but hope was fading, and high heels were looking more desirable these days, despite the adverse effects on the feet and back. Teague’s hair was a light brown; he had a lovely smile and there was something about the curve of it, or the slightly flirtatious way he looked at her, his glance flicking from her eyes to her lips and back again as he talked to her, something that reminded her of Billy, but she tried not to think about that too much.

On Eliza’s sixteenth birthday Teague turned up at the house and dropped off a small parcel for her, obviously containing jewellery. She was not in, so Richard received it on her behalf. “Are you planning to be my daughter’s married lover?” he enquired, with his usual directness. Teague was taken aback but decided to weather it with dignity.

“If you have no objection, Richard,” said Teague, holding Richard’s gaze without any defensiveness.

“If Eliza has no objection, I can’t see why I would,” he said. “Of course if you don’t treat her like a princess, I will have to kill you.”

“Understood,” said Teague, and that was all that was said. Usually, in the old days, a man would approach a girl’s father for permission to pay his addresses, and perhaps this was a modern variation.

So in due course, after a bit of to-ing and fro-ing, Eliza and Teague found themselves in sole possession of the house, sitting together on the couch. She was being passionately kissed, and passionately kissing him back. And then she was lying on the couch and had pulled him towards her, so he was lying on top of her and continuing to kiss her. For the average sixteen year old from a respectable middle-class background, a young man could expect there to be quite a lot of this, over quite a long time, before he would get any further. But Eliza was not your average sixteen year old, and her family was neither average nor respectable. Nobody had told her how to play games like What sort of girl do you think I am?, and she was very attracted to Teague. The feeling of being pressed against a hard male body excited her beyond all reason, and her thighs flew apart without her permission, wrapping themselves around his, the better to feel the bulge in his pants against her.

They ran up the stairs and made love in her bed, hurriedly the first time, and Eliza found that although Teague wasn’t Billy, her libido was her own. She found her new lover to be skilled and sensitive, and he in turn found her to be more responsive and less inhibited than he would have expected of a sixteen year old, or even perhaps a thirty year old. The fit was very nice indeed. It took Eliza’s mind off Billy, and Teague’s mind off other women who might have threatened his marriage.

Eliza had some rules for him. He must never cause Annicke to be suspicious, by his attitude or behaviour. Even if it meant leaving Eliza in the lurch without an explanation. “If she finds out, or even starts questioning you, it’s over,” she said. She did not really believe in betraying the sisterhood, and certainly not in breaking up their marriages.

Teague was fond of both Irish and Bluegrass music and so it was he who first introduced Eliza to a group of musicians starting up a band named “Pig in a Pen”, which they always intended to change. To Eliza it was like talking her own language with a different accent, so she jumped in with both feet, abandoning, for the time being, her classical violin work for the rush she experienced in playing with the band. Sometimes they busked in Sydney streets, at open air functions, or places where she could legally go, which did not include the pub or any venue where alcohol was served. Although there was another fiddle player who could work these venues, the rest of the band was champing at the bit for Eliza to reach eighteen. They would normally have settled for the legal-age fiddler but it was obvious they could not let Eliza go, and two fiddlers had to be better than one.

The timing was perfect, as Eliza had begun to feel like a mechanised violinist as she practised with the orchestra on playing incredibly quickly and perfectly in time. Such technical perfection was fascinating to listen to, and for her, as a musician, painfully lacking in soul.

Teague did not join the band himself, as it could draw undesirable attention to their affair. Eventually, inevitably, after almost a year of illicit but discreet frolicking, he decided to take his marriage seriously and part from his very youthful mistress, because Annicke was by then six months pregnant with their first child. He had come closer to falling in love than Eliza had, but parting was a sad business for both of them.

Perhaps it is a necessary part of every woman’s young life to have an affair with a married man. Heaven knows there are enough of them hanging out for it. Eliza didn’t feel guilty but it reinforced her belief that men did not readily engage in exclusive relationships. She wasn’t sure she could, either. Fifty years making love with the same person, my god, she thought, deciding it would be enough to make you want to join a nunnery or take to drink.

* * *

With Teague’s departure, Billy’s spectre began to haunt Eliza again, and she began exploring the internet for signs of his progress. She found it, in terms of guest spots on TV series and parts in movies. It seemed that at close on twenty-three he was moving fairly frequently between London and the States, and although he was not attracting much press attention, he had a devoted following of quite obsessed female fans. She knew a bit about the classification of mental disorders, but nothing at all about the classification applied to celebrities. Definitely not A-list or B-list according to the criteria, but C-list didn’t really apply either. He was just a young actor who was well known in some circles, probably fairly high on a number of prominent agencies’ casting lists and always working. She was proud of him, more so, perversely, because he wasn’t super famous like those people who were notorious for being in and out of rehab and hounded by the paparazzi. She referred to them as the papilloma: a kind of excrescence hanging onto people’s skin and feeding from their blood supply.

Eliza promptly had a dream in which she was walking through Dover Street Market, and he was coming the other way with a blonde on each arm. She greeted him, but he only looked her up and down, saying, “and who the hell are you?” This is not how Billy would behave but it still felt real when she woke up. She returned to her studies with a shudder but she was not happy.

A couple of years previously, when first they’d arrived in Sydney, it had been clear to Eliza that, having settled into a new country, a new school and a new dwelling, the next logical step must be to acquire a new feline. Eliza had seen a most desirable specimen on a home and garden television programme, phoned several breeders, and informed her father that they were heading west at the earliest opportunity. As it happened, there was some delay in carrying out this plan.

In the end, forward motion coincided with the descent of the Misery-Guts Demon upon Eliza. She was miserable, and when Eliza was unhappy, everybody was unhappy, or so Richard believed. It didn’t occur to him to sit down with her and try to get her to talk about it, but he did remember the benefits of feline therapy.

The Blue Mountains, rising to a height of 3,000 feet, if one is still disposed to think in feet, are named apparently because of their characteristic blue haze. This haze is the result of oils from the Eucalyptus trees which grow cheek by jowl in the area. Dust particles, water vapour and short-wavelength rays of light are, I believe, also involved, but we need not bother ourselves with those. What we are concerned with is the Maine Coon, the breeder of which was located at the highest point on the mountains. There are many websites and many photos of these animals now on the internet and the two characteristics which stand out are Huge and Fluffy. They are also pleasant, well-mannered and don’t eat more than two or three wombats in a year, even fewer if they are fed well and housed in the city.

However … it is one thing to be warned that your kitten will grow into something which could weigh 9.1 kilograms, and quite another, a year down the track, to put it on your bathroom scales and see that it is equal to two standard house-cats or three Yorkshire terriers. Perhaps if Richard had heard the animal’s potential stated in imperial weight – 20 pounds – he would have listened more closely, but as it was, the MacLean household was improved by one kitten, about three months old. At that age, the cuddly little creature, named Warwick for no particular reason, gave little hint as to food consumption and the difficulty level of prising him out of Richard’s favourite chair. But Eliza was suitably distracted, having her own baby cat to care for, and Richard heaved a sigh of relief.

Eliza began looking forward to starting her precocious first year at university. She was absolutely fed up with being a schoolgirl in an all-girl school; she sometimes felt that she was a hundred years old and trying to fit in with a bunch of kindergarteners. She could hardly believe it when the previous Richard-based problems re-emerged with a new cast towards the end of Year Twelve. He had a romantic role in a long-standing TV series, and as usual the fans – teenagers to grandmothers – were gathering momentum. Eliza received some invitations she wasn’t expecting and this time she refused them all politely, with an excellent Regretful Expression and a Plausible Excuse, or so she thought.

This wasn’t good enough, however, for Mia Stevens who, Eliza knew, did not like her a bit. On one of her visits to the locker room, she was bailed up by Mia. A really dedicated bully never travels alone, so Mia was backed up by her trusty henchgirls, Zoe Liebermann and Phoebe Curtiss. They immediately began to bait her about being stuck up and too good to socialise with mere mortals, being the daughter of a celebrity, yada yada yada.

“Why do you say that?” asked Eliza, with a sigh. She could see which way this was headed and she wasn’t sure she could take on all three at once without blood being spilled.

“People invite you to their houses and you won’t accept, because you think they’re not good enough for you,” said Mia, petulantly.

“How do you know that’s the reason I refuse?” asked Eliza.

“Well, why do you refuse, then?” asked Phoebe, snarkily.

A fair question. “No comment,” said Eliza, who suddenly didn’t want to reveal herself too much to this belligerent threesome, and Mia pushed her, hard. Eliza staggered back, recovered, clenched her fist and, with remarkable restraint, resisted the temptation to slug the offender in the nose. Still, she was getting angry, so she seized Mia by the lapel of her jacket.

“Now listen up, bitch,” she said, having heard the phrase in a TV show recently. “Keep your hands right off me. It’s none of your business whose invitations I accept. My father has friends in low places, and if any of you comes near me again, for any reason, he will send some of them around to visit you, all of you!”

Mia was trying to pull away so Eliza let her go suddenly, and she lurched backwards. When Eliza walked out of the locker room, the three made no attempt to follow. Eliza probably should have been an actress, because she certainly convinced the ghastly trio she was not to be trifled with, however her bravado deserted her once she got around the corner and her knees started shaking.

“I’m sick of this!” she told Richard that evening, and repeated her cri de coeur: “I want to be normal!” She explained what had happened, and what she had said, and to her annoyance he was inclined to be much amused. He appeared to be considering something highly entertaining for a few moments, then he turned to her again. “Do you want me to give them a scare, poppet?” he asked.

“How?” she said, “and yes, please.” He told her, and she forgot her indignation, laughing so hard that tears ran down her cheeks.

* * *

As Mia got out of her mother’s car after school, she noticed a black vehicle with darkened window glass parked opposite their house. Leaning against the car were two young men in double-breasted pinstriped suits, black shirts, white neckties and black hats. They had dispensed with the violin cases, a superfluous anachronism. One of them was looking down at what appeared to be a large knife, which he was ostentatiously sharpening with a stone. The other man stared at Mia, and when she caught his eye he tipped his hat to her. She gasped, and ran inside the house.

The men lounged around, menacingly, for a few more minutes, and then departed. They did not bother to repeat the performance at Zoe’s or Phoebe’s. Mia was the ringleader and she was the chosen one. It worked wonderfully well, and Eliza was not bothered again. She always greeted them cordially thereafter, and they responded politely, if somewhat anxiously. Eliza thought they had been rather easily scared by a couple of clichés.

The two young drama students reportedly thoroughly enjoyed themselves getting kitted up as gangsters and pretending to sharpen a rubber knife. Richard paid them for their time but they would probably have done it happily for free.

* * *

So at last Eliza’s schooldays drew to a close, much to her relief. After Teague, she decided that she rather liked having sex from time to time. She knew enough about the double standard to avoid the Eager Hounds effect. She sought out her occasional lovers, none of whom realised she was the one doing the seducing, from areas of endeavour other than acting, just for comparison. She wasn’t sure she ever wanted to get married, but she had no intention of being celibate for the rest of her young life.