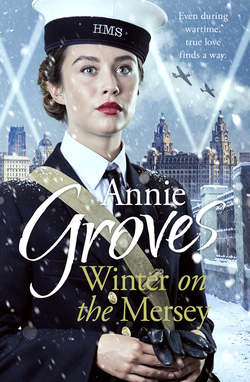

Читать книгу Winter on the Mersey: A Heartwarming Christmas Saga - Annie Groves, Annie Groves - Страница 7

CHAPTER TWO

ОглавлениеKitty Callaghan pushed a dark curl out of her eyes as she squinted at the keyhole in the fading evening light. There was just enough brightness left in the sky to find it. Of course there would be no street lamps coming on as they hadn’t been permitted since the outbreak of war. In a big city Kitty would have felt happy to stay out longer, knowing that there would be other people about, even if it meant navigating the potholed pavements with a shielded torch. Yet here, in this small town on the south coast, she felt reluctant to come back after dark. She wasn’t a country girl and there was something about her billet’s isolation that made her uneasy. Not that she would admit that to anybody.

Pushing open the door with its flaking paint, she listened for any signs of the other occupants, but the place was quiet. She shared this small house with two other Wrens and their landlady, who had been only too happy to let out her spare rooms after her husband had been called up. The rooms were small but clean, with comfortable if slightly battered furnishings, and Kitty couldn’t complain. She’d had much worse. When she’d first joined up, she had had to share a big dormitory with the other trainee Wrens, sleeping on a bottom bunk and with absolutely no privacy. Then there had been the filthy fleapit she’d been allocated when she’d been transferred to Portsmouth, which she’d managed to leave by claiming it was too far from her place of work. It wasn’t as if she came from anywhere grand either. Her terraced home on Empire Street was no bigger than this and certainly hadn’t been as comfortable, although she’d done her best. But having to run the household pretty much single-handed after her mother had died so young had been a struggle. Her big brothers had tried to help but their father drank away all the money that should have gone towards the housekeeping, and so it had been a matter of survival, with nothing left over for little extras. If it hadn’t been for their kindly neighbour, Dolly Feeny, they’d never have got through.

From Portsmouth Kitty had been transferred again to this small town hugging the coast. It was an ideal place from which to pick up signals from the continent, and in her capacity as a telephone operator she was much in demand. She had proved herself to be calm in the face of crises – when messages were arriving at an impossible pace, she was efficient in recognising which to prioritise, and unflappable when the callers were panicking or aggressive. Fortunately that didn’t happen often. But you never knew what or who you would be dealing with down the line and it was important to respond appropriately. Lives might be lost otherwise. Her exemplary work had led to her rising to the rank of Leading Wren, and everyone could see that this was well deserved.

The door to what had once been the sitting room opened and a young woman poked her face out into the corridor. ‘Oh, it’s you, Kitty. I thought I heard something. Fancy a game of cards?’

‘Sorry, did I disturb you, Lizzie?’ Kitty smiled at the young Wren who now used the ground-floor front room as her bedroom.

‘No, I was just writing a letter home … You don’t fancy playing cards for a bit, do you?’ Lizzie looked wistful, and Kitty remembered how homesick the girl had been when she’d first arrived. Maybe she should make the effort and play cards with her to try to cheer her up. But the truth was she really didn’t feel like it.

‘Maybe just one round, and then I think I’ll go up, if you don’t mind,’ Kitty said apologetically. ‘It’s been a long day.’

Lizzie nodded. ‘That would be nice; I need to finish my letter afterwards anyway. Mum and Dad are always going on at me for not telling them enough of my news.’ She opened the door to her room a touch wider and Kitty went in, sat at the little wooden table in the small bay window, and prepared to play. But her mind wasn’t on it and Lizzie beat her easily.

‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘I wasn’t much competition there, was I?’

‘It’s all practice,’ said Lizzie, not hiding her delight at beating her housemate, who was usually a sharp player. ‘Better luck next time.’

Kitty pulled a rueful face and stood, going through into the empty kitchen. Carefully she drew the blackout curtain before putting on the light and reaching for the tea leaves. She took a small scoop, mindful that there was only ever just enough to go round. She wondered whether to turn on the Bakelite wireless but decided against it.

The other Wrens in the house were lively and meant well, but Kitty found it hard to be anything other than superficially friendly with them. It wasn’t just because of the age difference; although she was older, it wasn’t by much. She just didn’t have a lot in common with them. Technically she was their superior in rank, which set her a little apart, but it was more than that. They were keen to go out, have fun, make the most of what little entertainment this place could offer. She wasn’t.

Once she had been, but that was before Elliott had died. It had been over two years now, but Kitty knew she would never again be that young Wren eager for adventure. Dr Elliott Fitzgerald had shown her a side of life that she had never thought would be open to her when she’d first met him. He’d been working in the hospital where two of her brothers were being treated, and she had found it hard to believe that he’d preferred her company to that of all the many pretty nurses he saw day and night. Yet he had, and their courtship had stood the test of separation, with him remaining in Liverpool while she began her training in north London. He’d given her confidence, stability, faith in herself and hope for a shared future – until he’d been killed in one of the final raids of the blitz over Bootle. After that she had hardened her heart and directed all her time and energy into her work. There seemed little point in going to nights out at the local hall or nearest air base. Elliott had been a wonderful dancer – even a champion when at medical school – and once she’d had him as a partner and tutor, there was little chance anyone else would come close. She didn’t begrudge her co-billettees their evenings with the airmen, but had no wish to join them.

Slowly she made her way upstairs, carrying the tea, relishing its welcome warmth in her hands. Her bedroom faced the back garden and she stood at the sash window, looking at the vegetable beds in the last of the daylight. Her landlady had dug over her lawn and taken to supplementing the rations with home-grown produce. Soon it would be time to start spring planting, and Kitty had offered to help. Whenever she was home on leave she would be roped in to help in Dolly Feeny’s victory garden, so she knew a little of what she was meant to do. She’d never begrudged helping Dolly on her precious few weekends back home, as it was largely thanks to the Feenys that the young Callaghans had survived their childhoods. It had made the two families particularly close. At one point Kitty had fancied herself falling for the oldest Feeny son, Frank; but now she knew better. He saw her as another little sister, and there had been no more to it, no matter how fast her heart had pounded at the sight of him. These days he was walking out with one of the young women based at his place of work and that was much more suitable all round. She forced her mind away from the image of them together.

Turning back to her room, she sat on the narrow bed with its rather worn candlewick spread, setting down the tea on a little wooden table that the landlady’s husband had made. Kitty sighed. The other reason she wasn’t keen on spending the evening playing cards with Lizzie was that she couldn’t help contrasting her with the two friends she’d made when they had all been trainee Wrens together. Both of them had known and liked Elliott and had helped her through the bleak time after he’d died. Then they’d all gone their separate ways, but had resolutely stayed in contact, mostly by letter, meeting up if their work allowed.

That was what Kitty had been doing today. Marjorie was someone she would never have met if it hadn’t been for the war: a teacher, who had moved in very different circles to those of Empire Street. Kitty had been overawed by her cleverness to begin with, but then again Marjorie had been shy, ill at ease with the opposite sex, unsure of herself in social situations. Kitty had grown up with three brothers and had then managed their local NAAFI canteen, and so was completely at home with young men and their teasing banter. Gradually she had realised her humble beginnings didn’t matter now they were all throwing themselves into the war effort, and Marjorie had relaxed enough to enjoy dancing with the young men from the Forces they’d met in the clubs Elliott introduced them to whenever he’d managed to visit London. She’d always been deadly serious about her work, though. She had been picked out for her brains and aptitude with languages, and was now stationed not far from her own home in Sussex, where she’d been working in signals. That was the official version, anyway.

When they’d met for lunch today, Marjorie hadn’t exactly contradicted that idea. However, she’d insisted on taking the corner table in a quiet little café, far from where anyone could overhear them, staring at the chequered cloth as if trying to decide what to say. Finally she had looked at Kitty and given her a small smile. ‘Look, you know how it is,’ she said. ‘I’ve been given a new posting and thought we should meet up before I left. I can’t say when I’ll be going, but it’ll be sooner rather than later.’

Kitty had raised an eyebrow, desperate to know more but only too aware that you didn’t ask questions.

Marjorie shifted in her seat. She was still birdlike, seemingly tiny enough to be blown over by the first hint of a strong wind. But Kitty knew inside she was made of sterner stuff. ‘So, I realise I can’t tell you what I’ll be doing but – well, this one I really, really can’t tell you.’ She rolled her eyes. ‘You’ll just have to put two and two together, Kitty, like I know you’re good at doing. Who knows, one day you’ll be putting through a call that’s a result of what I’ve been up to. That’s as much as I can give away.’

Kitty had sat up straighter. Adding that to Marjorie’s crammer courses in French and German, this was a strong hint that her friend was going to be sent abroad – and that must mean it was very hush-hush. There were rumours of young women being sent on secret missions into enemy territory. Now maybe her friend was to be one of them.

‘Really?’ Kitty was impressed and filled with trepidation on Marjorie’s behalf. ‘And you are happy about it?’

Marjorie’s chin went up and her eyes were alight. ‘Yes, absolutely,’ she’d said. ‘I can’t tell you what I’m doing, Kitty – but I can tell you I’m pretty darn good at it.’

Kitty nodded. Coming from someone else it could have sounded like boasting, but Marjorie had never been like that. For all her social awkwardness to begin with, she’d never had any doubts about her academic abilities. She’d had to fight her family for the chance to use those talents as a teacher and now she was turning them to good use in the service of her country.

Kitty had grinned. ‘Well, good luck then.’ She’d raised her tea cup. ‘And let’s hope wherever it is there’ll be some dishy airmen to fill your leisure hours.’

Marjorie beamed. ‘Suppose there might be. It’s hard to say – they never brief you on all the really important things like that. If I’m really lucky there’ll be some fair-haired ones. That’ll take my mind off work very nicely indeed.’

‘Marjorie!’ Kitty pretended to be shocked, but she knew there was nothing Marjorie liked better than being whirled around the dance floor by a fair-haired pilot, particularly if he’d promised her a martini. It didn’t hurt to dream. Though there might not be many cocktails for her friend in the near future.

They’d parted shortly after, with hugs and promises to keep in touch if possible, and neither had given in to the thought that Marjorie was going into danger and they might never see one another again. Kitty picked sadly at the bedspread now, wondering what was in store for her friend. She didn’t doubt she had reserves of courage and resourcefulness, but she had seemed so small as she’d waved her goodbye on the train platform. ‘I haven’t been able to see Laura,’ Marjorie had said. ‘I’ll write of course, but if you see her, will you tell her I was thinking of her?’

‘Of course,’ Kitty had promised. Laura was the third of the group who’d bonded so closely during the initial weeks of training. She was still in London, working as a driver, horrifying her very well-to-do family with her willingness to get her hands dirty fixing engines rather than sitting in their ancient pile in Yorkshire making polite conversation.

Clearly Marjorie was so close to being sent off to do whatever it was that she couldn’t even make it up to London; if that was the case, perhaps Kitty could go in her stead. She brightened at the thought. She’d see when she next had leave and if it coincided with Laura being able to take some time off. That would be something to look forward to.

Danny Callaghan drew the rickety wooden chair closer to the fireplace. He had lit the kindling when he’d got in from work, and now he poked it and added a few pieces of coal, just enough to take the chill off the room which had been empty all day. He warmed his hands and then reached into his pocket for the letter he’d picked up off the worn doormat. The writing was familiar, scrappy and uneven, clearly done in a hurry.

Ripping open the envelope he was curious to see what his young brother Tommy had to say for himself. Tommy wrote often but never at great length. He had been evacuated to the same farm as their neighbour Rita’s children, where he’d soon taken to the life. Seth the farmer had been delighted as, having no son of his own, he had begun to struggle with all the daily tasks once his young farmhands had been called up. Tommy had become a real help. The arrangement suited everyone. In the past Tommy had been a proper handful, and had nearly got himself killed in a burning warehouse down at the docks, where he had had no business being in the first place. His older siblings had been at their wits’ end trying to work out how to keep him safe at home, and so sending him to the farm had been the best solution all round.

Danny drew out the single sheet of paper and scanned it quickly, then looked again more carefully. He’d been expecting more of the same sort of news that Tommy had been sending for the past couple of years: what fences he’d helped to mend, if the fox had managed to get into the hen house, what treats Joan, Seth’s wife, had baked. There was some of that, but the main reason Tommy had written was he wanted to come back to Bootle.

Danny groaned. Of course his little brother was growing up. He was thirteen now and would soon turn fourteen. It hadn’t escaped Tommy’s notice that this meant he could leave school. So he thought the best thing would be for him to move back in with Danny and then see if he could help the war effort in any way – he had heard that boys of fourteen could join the Merchant Navy.

‘Oh no,’ Danny breathed, knowing full well the sort of life that would mean. Plenty of the men and boys he knew who’d grown up around the docks had joined the Merchant Navy, and of course Eddy Feeny would come home with tales of what it was like, so Tommy knew all about it – or at least the tales of adventure, dodging U-boats, mixing with seamen of all nations, all working for a common cause. It would appeal to any boy. But Danny didn’t want his little brother to be in danger like that. He groaned aloud once more.

‘Danny! Whatever’s the matter?’ Sarah Feeny pushed open the back door and set down a scratched enamel pot on the hob in the back kitchen. ‘Mam made extra stew and thought you might like some. Don’t get your hopes up; it’s nearly all potato and beans, hardly any meat in it. Seriously, what’s wrong? You haven’t taken bad again, have you?’ Her animated face was etched with sudden concern.

‘No, no, nothing like that.’ Danny shook his head and his thick black hair glinted in the firelight. ‘You shouldn’t have.’ He nodded at the pot. ‘Thank your mam for me, she spoils me.’

‘She likes to,’ Sarah said with a grin, pulling up another chair. ‘So, tell me what’s happened.’ She shivered and drew her nurse’s cloak more tightly around her.

Danny let out a long sigh. ‘It’s our Tommy. This arrived today. He’s reminding me that he’s going to be fourteen soon and won’t have to go to school any more. He says he wants to join the Merchant Navy.’

Sarah gasped. Like Danny, she thought of Tommy as the young tearaway who’d settled down once he was given responsibility on the farm, and although if she’d added it up rationally she would have known how old he was, it was still a shock to realise he was well on the way to becoming a young man. ‘It doesn’t seem possible, Danny. Surely you don’t want that.’ She tried not to let her anxiety show, not only for Tommy but for Danny too. She knew better than anyone what he struggled so hard to keep hidden. Although technically now part of the Royal Navy, Danny had never gone – and could never go – to sea. All of the armed forces had turned him down, despite his obvious courage and willingness to sign up, as rheumatic fever had left him with an enlarged heart. Any extreme physical activity would put him at risk. They’d only found out when he’d stood in for a fallen fireman at a vast blaze down at the docks. Danny had taken the man’s place without hesitation but had collapsed afterwards. Sarah had rescued him but the news had got out. When it came to fighting for his country, Danny Callaghan was damaged goods.

By a stroke of luck, Danny had shown an uncommon aptitude for solving puzzles and crosswords while recuperating, and this had led to him being recruited to join Western Approaches Command, as they were in desperate need of that rare kind of skill to help decipher enemy signals. Frank Feeny worked there as a naval officer, and had recommended his old friend, against some opposition from the more traditional superior officers. Danny had only ever worked down on the docks up till then and had been a tearaway himself when in his teens.

This was exactly what was on Danny’s mind as he reread his little brother’s letter. He recognised that feeling of wanting to join up, do his bit, and also see the world and test himself against the odds, take a risk and worry about the consequences later. It was precisely why he wanted to protect Tommy from it. Now he was older, he wished he’d paid more attention at school, but at the time he couldn’t be bothered, couldn’t wait for it to end so he could get out and live his own life. It had meant that his work at Derby House had been extra hard to begin with as he’d had to learn so much from scratch. He could see with hindsight how he would have benefited from listening to his teachers when they’d insisted he could have gone further. All right, the family had needed him to go out and earn his keep – but he’d wasted the last year in the classroom. He wanted better for Tommy.

Now he looked across at Sarah, with her sleek brown hair pulled back away from her caring face, knowing that she’d be worried for him. He didn’t want his anxieties to burden her. ‘No, I’d much rather he stayed where he is. At least we know he’s safe there, and well fed.’

‘And Michael and Megan look up to him,’ Sarah said. ‘They’d miss him if he came back.’

‘It’s been good for him to be like a big brother to them,’ Danny agreed. ‘The trouble was, we all let him get away with murder because he was the youngest and he could wind us round his little finger. Now he’s had to grow up a bit.’

‘Sounds like he’s started to grow up a lot,’ Sarah said ruefully, getting to her feet and opening a cupboard. ‘Here, Danny, I’ll put this on a plate so you can have it now while it’s still warm. News always feels better after a full meal.’

She knew her way around the Callaghan kitchen as well as her own, as – ever since Kitty had left – Dolly would often make a bit extra for Danny and have Sarah take it across the street. ‘There you are.’ The delicious smell filled the small room, and Danny tucked in gratefully.

‘Thanks, Sar.’ Finally he pushed the plate away. ‘You’re right. You can’t make good decisions on an empty stomach.’

‘I wonder what Kitty thinks?’ Sarah replied. ‘Do you think he’ll have written to her as well? It’s not up to just you, is it?’

‘She’ll have to know,’ Danny said. ‘Even if he hasn’t asked her, I’m going to tell her. Sometimes he listens to her. She can persuade him to stay at the farm better than I can.’

‘Not much she can do about it from wherever it is she is down south,’ Sarah pointed out. ‘All the same, you’d better write to her. And she’ll want to know all about the new baby. Mam sent everybody a letter to say Ellen had been born but didn’t have time to give any details.’

Danny looked sceptical. ‘That’s more your sort of thing, isn’t it? I don’t know what Kitty will want to know. I’m glad for Rita, of course I am, but all babies look the same to me.’

‘Danny!’ Sarah gave him a straight look. ‘That’s your niece you’re talking about. Honestly, you men, you’re hopeless sometimes.’ Her expression was affectionate though. She could never be truly cross with Danny. He was too good a man for that. She knew he was just teasing – in that special way he seemed to reserve just for her.

‘You tell me what she’ll want to know, then,’ he grinned. He had realised long ago that Sarah knew him better then he knew himself. ‘Better still, write a note and I’ll put it in with my letter about Tommy. That’ll sweeten the pill.’ He grew serious again. ‘Sar, just think of it, young Tommy wanting to put his life on the line like that. I can’t have that. It’s too much. Somehow, we have to stop him.’