Читать книгу Winter on the Mersey: A Heartwarming Christmas Saga - Annie Groves, Annie Groves - Страница 9

CHAPTER FOUR

Оглавление‘Are you sure you don’t want to go to Lyons Corner House?’ asked Laura as she met Kitty off the train at Victoria. ‘Somewhere nice and warm?’ She was in civvies, and even though clothing was rationed and generally hard to come by, she’d somehow managed to look devastatingly fashionable as ever, with her swing coat and little matching hat on her beautifully cut blonde curls. Heads were turning as she swept along the concourse but Laura blithely paid no notice.

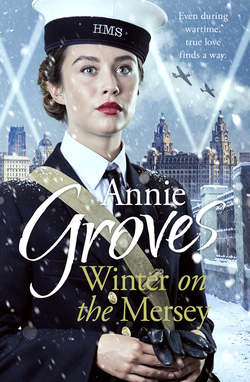

Kitty had come in her Wren’s uniform. Now she no longer shared a billet with Laura, her chance to borrow her friend’s clothes had gone, and she hadn’t felt like turning up in her slightly battered tweed coat, now several years old and looking it. Besides, she was proud of her uniform. She’d worked hard to be worthy of it, and she appreciated the approving glances it won from many of the other passengers whirling around them. She took her friend’s arm.

‘I’d really rather go for a walk, if you don’t mind,’ she said. ‘I’m cooped up inside most of the time, you know.’

‘Of course, I completely understand,’ said Laura at once. ‘But surely there are plenty of places to go walking where you are? What else is there to do, frankly? Count the cows?’ She glanced down at her feet. ‘Good job I didn’t wear my high heels. I found some divine ones in Peter Jones, did I tell you in my last letter? Anyone would have thought they were just waiting for me.’

‘Lucky you,’ said Kitty, meaning it. ‘Just don’t try driving your lorries in them. Tell you what, if we wander across Green Park we could find a Lyons after that. I don’t want to deprive you of your teacake.’

‘Come on, then.’ Laura led the way, weaving through the press of people, many in uniform, some carrying kit bags over their shoulders. Some were saying goodbye to families and loved ones. Others were waiting, maybe for a long-hoped-for reunion. Despite the ever-present threat of disruption to the trains, nobody appeared to be complaining. Kitty had been lucky; she’d come up from her small local station without a problem for once. It meant she had most of the day to spend with her old friend. Almost without realising it, she felt a weight lift from her shoulders. Confiding in Laura always made her feel better and she knew the feeling was mutual.

As they passed through the streets and headed towards the park, the crowds thinned out, but there was still a sense of bustle and activity. Kitty grinned, relishing being back in a big city. It was where she felt at home, jostling around people, being in the thick of it. Growing up on Merseyside had made her feel that this was normal, and it was where she was comfortable, despite knowing rationally that big cities were more dangerous, being targets for the enemy’s attacks. Yet she couldn’t shake off the sense that this was the sort of place where she belonged, not a quiet country town where everything went silent after dusk.

Green Park loomed ahead, with its avenues of old trees, and as they began to wander down one of its wide paths, Laura turned to face her. ‘All right, Kitty. I know you – you would usually rush straight to Lyons or somewhere like it. What’s up? What do you have to say that’s so secret you can’t tell me where anyone can overhear?’

Kitty laughed ruefully. She should have known there would be no fooling Laura, who might act the dizzy socialite when it suited her, but who underneath was as sharp as a tack. There was no point in beating about the bush.

‘Have you heard from Marjorie recently?’

‘Marjorie?’ Laura stopped to think. ‘I had a letter a few weeks ago; it had taken ages to get to me, and loads of it had been censored anyway. You wouldn’t think signals in Sussex could be that exciting. I was impressed.’

Kitty shrugged. ‘Well, let’s just say if she wrote down what she hinted at to me the other day, then you wouldn’t have had much of a letter at all. It would all have been blacked out.’

‘Now you have got me intrigued,’ Laura said. ‘Tell all, Callaghan. Out with it.’

Hoping that she wasn’t exaggerating, or hadn’t got the wrong end of the stick, Kitty explained what had happened. ‘So you see, she asked me to have a word with you rather than write, as she didn’t think she’d be able to get leave to see you in person,’ she finished, gripping her handkerchief in her jacket pocket in anxiety for her friend. ‘This sounds serious, doesn’t it? Can you imagine it, Marjorie going into enemy territory, probably undercover?’

Laura came to a halt. ‘Well, I don’t know what I expected you to say, but it wasn’t that,’ she admitted. ‘I thought you were going to tell me that she’d finally fallen properly for one of her blond pilots, or she’d been chosen to learn Danish or one of those other language things she gets so worked up about. Golly, Kitty. That’s ever so slightly terrifying, isn’t it? I mean, when we first knew her, she was scared of Leicester Square on a Saturday night.’

‘She’s changed since then,’ Kitty reminded her. ‘She was so certain she was doing the right thing as well. Honestly, Laura, she showed no doubt at all. She knows what she’s getting into and she’s ready for it. I’m afraid for her and yet I’m proud too. That she should be chosen – well, she must be really good at what she does.’

‘She is, I’m sure,’ said Laura with certainty. She held on to Kitty’s arm more forcefully. ‘Look, we mustn’t worry about her. That will do no good and we can’t change what she’s decided to do or what will happen. She will be needed.’ She paused, casting her glance from left to right and back again. ‘No one around, is there? Well, I bet she is going to northern France.’

‘What?’ Kitty leaned closer. ‘What do you mean? What do you know, Laura?’

Laura closed her eyes briefly and then made up her mind to share what she’d heard. ‘All totally hush-hush, of course,’ she said, as if it was even necessary to stress such a thing, ‘but it’s sort of common knowledge in certain circles that something big is going to happen. I don’t know when, and of course not exactly what, but something’s brewing.’

Kitty raised her eyebrows. ‘Has Peter said something?’

Captain Peter Cavendish was Laura’s boyfriend, and very well connected, with an uncle who was an admiral and who had attended meetings of naval top brass ever since they’d known him. At first Laura had called him Captain Killjoy, as their working relationship had begun with hostility on her part and near-silence from his; he’d also shown an uncanny knack of knowing when Laura had planned a night out, always calling her to drive him just when she was getting ready. That had lasted until they’d both been involved in rescuing a baby from a burning building after a bomb had gone off in a north London street. Peter had nearly died, and after that it had become obvious that the two of them were meant for each other.

‘Not as such,’ Laura admitted. ‘You know he’s careful never to breathe a word of what goes on at those interminable conferences of his. But I can tell something’s changed. I mean, it makes sense. Look at all the Allied success of the past year – North Africa, Italy. You’d have to say it would be no surprise if they were thinking of going into France now. Wouldn’t you, if you were in charge?’

Kitty took a step back. ‘I … I don’t know. Seeing as I’m never going to be in charge of something like that, I don’t think about it. I just get on with what I’m asked to do.’

‘Oh, so do I,’ Laura said hastily. ‘I’m just guessing. But it would be the obvious thing to do.’

Kitty glanced at her friend. Of course she would hear conversations like this all the time, even if they weren’t full of detail. But Laura was used to being around discussions at that sort of level. Kitty wasn’t, and she didn’t feel qualified to offer an opinion. Also, even after having been friends for so long, Laura sometimes still had that effect on her: making her feel inadequate, that she was on the outside looking in, while the likes of Laura forged ahead, effortlessly taking charge, knowing they were born to make the key decisions. Then she gave herself a mental shake. Laura didn’t do it deliberately. It was just Kitty’s own habit to feel under-confident in the face of such assurance. But Kitty herself had changed since the early days of training – she had to remember that.

‘Besides,’ Laura said, her tone sadder now, ‘he’s been hinting that he might not be shore-based for much longer. Nothing definite, naturally. But it’s true; ever since I’ve known him he has been mostly behind a desk rather than on board a ship. I can tell he misses it, and he feels he should get back to sea and into the heart of the action. I admire him for it, of course I do, but I can’t help wanting him to be safe as well.’

‘Oh, Laura.’ Kitty gave her friend’s arm a squeeze. ‘He’ll have to go where he’s sent, won’t he? Like the rest of us. We know he’s brave, there’s no question of that.’

‘He feels he hasn’t taken his share of the risks,’ Laura said flatly. ‘We both know it was taking the risk of jumping through that window with all the shattered glass that injured him, so you can hardly accuse him of taking the easy way out with a desk job. They had to keep him from active service for ages while he built up his strength again – not that you’d get him to admit it. But he feels everyone thinks he’s taken the cushy postings, when really the opposite is true. He lives with the consequences of that injury every day; he’ll never be fully free from pain.’ She pulled a face. ‘Anyway, there we are. Nothing I can do about it. If he does take part in whatever’s coming up, maybe he’ll bump into Marjorie, to say bonjour.’

Kitty gazed up to where the tree branches almost met in an arch above their heads, the new leaves beginning to bud. ‘It feels like it’s all a long way off, doesn’t it? Standing here in this quiet bit of the park.’

For a moment it was easy to forget that they were in the middle of the biggest city in the country, millions of people going about their business to fight for everything they held dear. The spring sunlight filtered through the swaying branches with just a hint of warmth to come.

Laura smiled. ‘Yes, but it’s not, is it? So, my girl, we have to grasp every moment. And in my book that means a nice cup of tea and maybe a cake if they’ve got any. Or a crumpet at least. Come on, I’ll treat you.’

Kitty relented. Laura clearly wasn’t going to be kept from a café for much longer. ‘All right, you win,’ she said. ‘Now you know the news and I know yours. Peter’s all right otherwise, isn’t he?’

Laura gave an even bigger smile. ‘Yes, still the dashing captain.’

Kitty knew that Laura had tried to keep her friendship with Captain Cavendish under wraps, as such relationships, while not exactly frowned on, and not uncommon, were not actively encouraged within the service. Once it had come to light, there had been a fair bit of jealousy of Laura and some very hurtful comments had been aimed her way. It being Laura, they had just bounced straight off her, but even so, Kitty was aware her friend never put herself forward for promotion or any kind of privilege, concerned that the immediate assumption would be that her boyfriend or his illustrious uncle had used their influence. Laura loved her job as it was, and she was very good at it, but Kitty wondered how long that would last, especially if Peter was called back to active service as seemed likely.

‘As long as you’re happy,’ Kitty said loyally.

‘I am,’ Laura assured her. ‘He’s the best thing that ever happened to me, I don’t mind telling you, and even better he says the same about me. I just adore him, however foolhardily brave he might be. Wouldn’t have him any other way.’

Kitty nodded, pleased for her friend. ‘And no news about—’

‘No, none,’ Laura said hurriedly. She didn’t have to check what Kitty meant; there was one person they both knew was never far from Laura’s mind. Her cheerful attitude masked a deep-seated sorrow for her lost brother, a pilot missing in action since before they had started their training. No confirmation had ever come about what his fate had been, and so there was no way of knowing if he was alive or, more likely, dead. So Laura kept going, trying to remain positive, but with a little bit of hope dying away every day.

‘No, nothing. Of course I’d tell you if there were. And who knows what might happen if we invade France? I might at least find out, one way or the other. But for now it’s limbo as usual. Come on,’ she tugged on Kitty’s arm, ‘I’m perishing. I’ve put on my most glamorous new coat for you, I hope you recognise, and it turns out to let the breeze right through it, so if I don’t have a hot drink soon I might well expire, and you wouldn’t want that on your conscience, would you?’

‘Definitely not, Peter would kill me,’ said Kitty, allowing Laura to lead her towards Piccadilly and the promise of tea and crumpets.

‘So will you look after Georgie on Saturday evening, Mam?’ asked Nancy, quickly checking her reflection in the mirror over Dolly’s fireplace. She carefully smoothed her victory roll, making sure every hair was in place. She had red hair like her sister Rita, but Nancy’s was more Titian in tone, and she always styled it, whereas Rita usually made do with anything that was tidy enough to fit under her nursing sister’s cap. Nancy nodded quickly in satisfaction. She’d been told she had a look of Rita Hayworth about her, and thought there might be some truth in it.

Dolly looked up from the comfy armchair, where she was knitting something in mustard yellow with wool unravelled from Violet’s old cardigan, which had finally given up the ghost. ‘Saturday evening? Are you off out, young lady? Don’t forget your poor husband, stuck in a Jerry prison.’

‘Of course I never forget Sid,’ snapped Nancy, annoyed, ‘but it doesn’t mean I have to spend every hour God sends with his miserable mother in her horrible house. Honestly, Mam, she keeps it so cold it’s a wonder I haven’t turned blue. It’s making Georgie ill, I swear it. He’s got a bad chest again, poor little soul.’ Sid Kerrigan had been a prisoner of war since Dunkirk and had never even seen his little boy. Now and again Nancy felt guilty about that, but usually she was too preoccupied by the idea of her youth disappearing fast and having nobody to go dancing with. ‘Anyway, it’s not as if I’m off gadding about. My WVS group has joined forces with the WI to put on a dance for the visiting servicemen and they need volunteers. Of course I said I’d help out when they asked. They rely on me for that sort of thing.’

Dolly sighed. She’d tried for ages to get Nancy involved with the local branch of the Women’s Voluntary Services, of which she was a mainstay. Then Nancy had outmanoeuvred her by announcing she was indeed joining the WVS, but the branch in the city centre. Nancy assured her mother it was because they were most in need of help – and as it was just after the dreadful days of the Liverpool Blitz, this was true – but it also had the advantage of being away from her mother’s eagle eye, and mixing with the influx of American servicemen, a trickle which grew to a flood after Pearl Harbor. Nancy was fooling nobody – and the fact that she was never without a new pair of nylons spoke volumes. Dolly had a pretty shrewd idea what Nancy got up to in order to get them, but she had no proof. She wasn’t going to stand for her middle daughter letting the family down, and had warned her often enough. Now she had another reason to object.

‘That’s all very well, Nancy, but I said I’d have little Ellen that evening,’ Dolly told her. ‘Rita’s worn out with her, and I promised to give her a few hours when she can grab some unbroken sleep. And no, before you ask, Sarah’s working, Ruby’s apparently going out with a friend and Violet is keeping the shop open late. I can’t risk having Georgie if he’s got a bad chest; he might pass it on to Ellen and she’s far too tiny to cope with that.’

Nancy all but stamped her foot in frustration. ‘But, Mam—’

‘Don’t you give me any of your soft soap, my girl,’ said Dolly sternly. ‘I love Georgie to pieces, and well you know it, but there’s someone else smaller than him to consider now. You might as well get used to it. You’ve got his other grandmother who could help out, after all.’

Nancy huffed in indignation. ‘I’d sooner let him play in the dock road. She’s useless, Mam, all she goes on about is how she’s suffering ’cos Sid’s a POW, as if she’s the only one who’s got anything to complain about. I wouldn’t trust her to notice when Georgie was hungry or if he needed anything. She’s not like you and Violet, you know.’ She turned on her dazzling smile, but it was wasted on Dolly.

‘Well, has she got him now?’ she demanded.

‘You have got to be joking!’ Nancy pouted. ‘No, she hasn’t.’

‘Where is he, then?’ Dolly wanted to know.

‘With Maggie Parker, as was. You know, Betty Parker’s big sister. Her house got bombed out and she’s moved back in with her family here and she’s got a kiddie just a bit younger than Georgie,’ Nancy explained. ‘I thought it would be nice for him to have a playmate the same age. Particularly if everything here is going to revolve around a new-born baby,’ she added crossly.

‘Nancy, you can’t be jealous of your own little niece,’ Dolly sighed in exasperation. ‘Betty Parker, now there’s a name from the past. She was Sarah’s best friend all the way through school, then she went and joined the Land Girls, didn’t she? They’re a nice family, so they are. Why don’t you ask them to mind Georgie on Saturday? It’s not as if you’ll be out late, is it?’ She gave her daughter a straight look.

Nancy squirmed, but couldn’t exactly say what she’d had in mind for Saturday. It certainly didn’t involve coming home directly after the dance. Common sense told her to quit while the going was good, though. ‘That’s an idea, I’ll ask,’ she said. ‘I’ll go and do that right away – it’s time I was picking Georgie up anyway.’

‘That’s right, love, you do that.’ Dolly approved of the Parkers, and felt she could rest easy that Nancy couldn’t get up to anything now. She picked up her knitting again, Pop coming though the back door just as Nancy went out.

Pop shrugged off the heavy donkey jacket that he wore for his salvage work, and turned to wash his hands at the kitchen sink. ‘Did I miss anything?’ he asked, coming through the narrow doorframe between the back kitchen and the kitchen proper. He bent to kiss Dolly on the cheek. ‘What did Nancy want? The usual?’

Dolly laughed up at him. ‘Of course. She can’t have her own way this time, though.’ She recounted their conversation.

Pop raised his eyebrows. ‘She’ll have to get used to the new way of doing things,’ he declared, running his hand through his shock of white hair. ‘We’ve helped her a lot and we’ll do so again, but she has to realise little Ellen needs us too. I don’t want our Rita took bad because she’s tried to do much too soon. You know what she’s like.’

‘You’re right, she’ll be angling to get back to work any day now,’ said Dolly, untangling a length of wool that had tied itself in a knot. ‘She’s not to rush it. We’ll have to keep an eye on her, see that she takes her time.’

‘She never thinks of herself, that one,’ Pop said. ‘What’s that you’re making there, Dolly? That looks familiar.’

‘So it should.’ Dolly held her work at arm’s length and inspected it critically. ‘It’s the wool from the cardigan Violet’s been wearing these past three years, which was more hole than cardie by the time I came to use it. I don’t know, it’s been washed so often it’s gone all scratchy and uneven. I reckoned I could make it into a bolero for her so she could still get the warmth, but we’ll have to see.’

‘If anyone can do it, you can,’ said Pop proudly. He never ceased to be amazed at his wife’s skill, even though they had been married thirty-odd years. She could sew, knit and cook, she was the street’s auxiliary fire-watcher, she ran make-do-and-mend classes as well as working for the WVS. She had raised five children, helped with three grandchildren so far and was hoping for more, though she never said anything in case Violet got upset. There was no doubt where most of their children got their work ethic from. He returned to the subject of the one child who hadn’t.

‘Our Nancy all right, was she?’

‘She’s got some do on, and says she’s been asked to volunteer. I don’t doubt she has, but it’s what she gets up to while she’s there that worries me.’ Dolly clacked her needles together. Both she and Pop were very strict about the sanctity of marriage and had brought their family up to hold the same view. That was why it had been so hard to stand by when Rita was married to that manipulative bully Charlie Kennedy, but Rita had never given them any cause to worry, even when he treated her so badly. The same could not be said for Nancy, who’d been caught out with Stan Hathaway, a local boy now in the RAF, in a bus shelter a couple of years back. Nancy had sworn nothing had really happened and she wouldn’t go so far again, but Dolly knew only too well what she was like.

‘Don’t see trouble where there isn’t any,’ Pop warned. ‘She’s a good girl at heart, our Nancy. You can’t blame her for hankering after a bit of excitement. Sid’s been gone a long time and she’s still young. It’ll all be harmless fun, you see if I’m not right.’

‘Yes, I’m sure that’s all it is really,’ said Dolly, not wanting to worry Pop. ‘Anyway, she’s found someone else to babysit occasionally, so all’s well.’

‘There you are then.’ Pop rubbed his hands in front of the little fire. ‘Now tell me something really important. What’s for tea?’

Dolly brightened up. ‘Funny you should ask. I found a recipe from the government that uses parsnips in a pudding, and we’ve just dug up the last ones from the victory garden. It’s perfect. You mix them with cocoa and milk and it says it’ll be just like a chocolate pudding.’

Pop’s eyes widened. Even with Dolly’s talent in the kitchen he couldn’t see how this idea would work. ‘Lovely,’ he said loyally. ‘Can’t wait.’