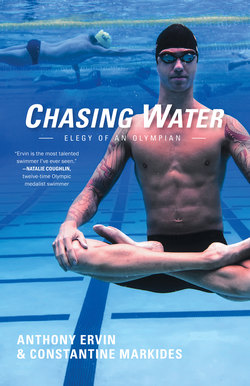

Читать книгу Chasing Water - Anthony Ervin - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4.

A Nervous Condition

Oh the nerves, the nerves; the mysteries of this machine called Man!

Oh the little that unhinges it: poor creatures that we are!

—Charles Dickens

F-f-f-feel like-a l-l-l-lightnin’ hit my b-b-brains . . .

—Willie Dixon, “Nervous”

One morning after Anthony had entered junior high, he and his brother Derek were on the couch watching Saturday cartoons. His mother walked into the den and right away noticed something out of the ordinary. Anthony’s eyes were rapidly blinking. It wasn’t the first time she’d seen this. On occasion it had happened before, but only for a few seconds. Since he’d recently been prescribed glasses, she’d always assumed it was an ophthalmological issue related to his nearsightedness. This time, however, it seemed more pronounced and longer lasting. “What’s wrong with your eyes?” she asked. He knew something was off but didn’t know what. Not wanting to interrupt the cartoon, he shrugged it off. The blinking soon passed, and they both forgot the incident.

A few weeks later, Sherry received a call from the pool. They told her to come immediately.

It happens toward the end of swim practice. That itchy feeling around my eye. It’s never happened before during practice. And this time, the tense feeling spreads downward. I can’t help but move my jaw as I wait on the wall. When I push off it stops. But when we get to the other wall it starts up again. Moving my jaw relieves the pressure. Like scratching an itch.

But this itch doesn’t go away. The guys in my lane are looking at me funny. They can’t see the blinking because of my mirrored goggles, but they can see my jaw moving side to side. The itch gets stronger. Now it’s happening when I’m swimming. Just before the turn in the shallow side, my head jerks down during my side breath. Instead of gulping air, I swallow water.

I stop at the wall, coughing, and scoot toward the lane line to make space for their flip turns. When I look up I see the coach walking toward me. She’s about to yell at me for stopping during a set. Then I see her expression change from mad to confused to worried. It’s hard to keep my eyes focused on her because they keep blinking and my head is twitching.

When Mom shows up fifteen minutes later, I’m still standing in the shallow end. I didn’t get out of the pool. I would have had to take my goggles off and they would see my blinking. The others have already finished the workout. Some are staring at me from the pool deck and saying things to each other. Only me and three older girls are still in the water. One is hugging me and I’m crying and I don’t want to cry and it’s embarrassing but I can’t help it. And I can’t help my head from jerking. What’s wrong with me? I don’t know what’s happening.

And then Mom rushes over and lifts me up out of the pool and she’s saying, “What’s wrong, Anthony? What’s wrong, Anthony?” and she looks scared, really scared.

Tourette’s syndrome is a neurological disorder typically first noticed in childhood, characterized by repeated involuntary or semivoluntary body movements and vocalizations. In 1972 it was believed that only one hundred people in all of the US had Tourette’s. Now it’s believed that one in every hundred Americans have Tourette’s, with two hundred thousand having the most severe symptoms. In milder forms, Tourette’s involves rapid blinking, throat clearing, and twitching. More rare symptoms include automatically repeating the words and gestures of others (echolalia and echopraxia), repeating one’s own words (palilalia), and involuntarily swearing and uttering obscenities, often related to feces (coprolalia). This last word translates in Greek literally to shit talker. Though only about one in ten people with Tourette’s exhibit coprolalia, there’s a widespread misconception that everyone with Tourette’s is subject to uncontrollable outbursts of profanity. This is also the de facto misimpression one gets from TV and other media (e.g., the South Park Tourette’s episode and the ranting “Tourette Guy” on YouTube).7

Little is known about what causes Tourette’s. In the fifteenth-century book Malleus Maleficarum, considered the first written account of what’s now called Tourette’s, a priest’s tics were believed to be “related to possession by the devil.” When it first entered the medical lexicon in the late nineteenth century, it was considered a “moral” social infirmity resulting from roguishness and a debilitated will. From the early- to midtwentieth century, it was characterized as a psychiatric illness requiring psychotherapy. Now that neuroscience has taken epistemological center stage, it’s seen as involving abnormalities in the brain and its circuitry, which affect the production and/or reception of dopamine,8 the neurotransmitter involved in initiating movement.

Although the exact cause of Tourette’s isn’t known, recent findings suggest the condition can confer advantages as well as impediments. Tourette’s can result in increased attention to detail and heightened awareness. Neurologist Oliver Sacks has noted that, while Tourette’s is often destructive in its effects, it “can also be constructive, add speed and spontaneity, and a capacity for unusual and sometimes startling performance.” In timed neurological tests for motor coordination, children with Tourette’s were faster than their peers. In other neuropsychological studies, they showed higher cognitive control: all those childhood hours spent trying to suppress tics served as a form of mental training. One can only guess at how this cognitive advantage and nervy sensitivity might play out when applied to a complex and sensory-rich environment like water, where feel and proprioception—the awareness of one’s body movement and position—are so crucial.

A 2014 20/20 piece exploring the possible relationship between Tourette’s and athletic excellence referenced two athletes. The first was the US soccer goalkeeper Tim Howard, whose performance in the 2014 World Cup was so impressive that Americans actually started watching soccer. The second athlete was Anthony Ervin.

* * *

The day after the pool incident, Anthony’s mother took him to the pediatrician, who suspected Tourette’s and referred him to a neurologist. After several visits that included sleep-pattern tests and a CAT scan to rule out a brain tumor, the neurologist diagnosed Anthony with Tourette’s. By now his blinking fits had escalated and would commence as soon as he woke up. Concerned about the stigma surrounding Tourette’s, Sherry asked that Anthony’s condition be listed in his school records as a “nonspecific neurological disorder.” As the family learned more about the condition, some of Anthony’s elementary school behaviors made more sense. Tourette’s is a complex struggle between the self and what feels like an outside force besieging it with physical and mental compulsions. This accounts for the variety of neurobehavioral conditions that can accompany Tourette’s like OCD and ADHD. Anthony exhibited tendencies of the former: washing his hands repeatedly; spending minutes on end before a mirror to make sure his hair’s part and curl were exact; lining up books in ascending order; grouping colors.

His mother suspects that much of the waywardness during his early years could be attributed to “Anthony dealing with things neurologically that nobody realized.” And though vocal and physical tics tend to subside with age, the depression, anxiety, panic attacks, and mood swings that can accompany Tourette’s often persist through one’s adult life. Anthony’s cognitive ability in later years to train and race with the undistracted tunnel-like focus of a racehorse with blinders also had a destructive counterpart: a tendency to obsess single-mindedly over disaster scenarios and then paralyze with anxiety over a sense of impending calamity.

A chronic but nondegenerative disease, Tourette’s has no cure, though it can be treated. Anthony was prescribed clonidine, a hypertension medication also effective in suppressing tics. They started him on a quarter of a pill. Five days later they increased the dosage to half a pill, but he was still subject to frequent blinking fits. Only when they increased the dose to a full pill did he wake up without blinking or twitching.

Not until later in high school, at higher doses of medication, did the tics fully come under control. In junior high, he was still subject to convulsive episodes. But aside from excessive swearing during emotional moments (which he admits he often indulged in simply because he had the medical excuse), his tics were more physical than verbal. Ervin likens the experience of a Tourette’s fit to watching an online video with slow connectivity where the clip keeps pausing to buffer.

Jackie recalls Anthony in junior high sitting on his bed, struggling to read: “It would take him forever to get through one page. His eyes would close, and he would lose track over and over again. It was heartbreaking.”

Lorac insane, dying . . .

“Raist!” he moaned, clutching his brother tightly.

Raistlin’s head moved feebly. His eyelids fluttered, and he opened his mouth.

What?” Caramon bent low, his brother’s breath **** Caramon bent low, his brother’s breath ****** head moved fee *** fluttered, and he **** eyelids fluttered, and he ** he opened **** fluttered **** opened his mouth *** his mou ** mo ** mouth *******

* * *

I can’t. I put down the book and wait for it to pass.

Here in my room, at least I don’t have to control it. I can just let it happen. At least here no one is staring at me and avoiding me like at school or like my old neighborhood friends. Everybody avoids me now. Only at swim practice do they act the same around me, probably because swimming is hard and we all do it and what we go through together and have in common is more important than what we don’t.

Yesterday I watched a nature show about animals living high up in the tall mountains. In one part there was a crazy snowstorm and nothing but snow and ice and darkness and freezing wind. It was the last place in the world you’d want to be. Most of the show was about nature and animals, but for one part during the snowstorm it showed the people who filmed it inside their tent, with a little light hanging over them. It was cramped inside and they could barely sit up in the tents and they were laughing and joking about having not showered for ages and didn’t seem to care at all about being crammed into that tiny space because they were warm and had each other. I remember that.

I remember the one bird stuck in the storm. It didn’t have a tent. It didn’t even have a tree. Just the ledge on the mountain. It ruffled its feathers and shut its little eyes and shrunk down into itself. It looked like a tiny statue someone had left on the mountain. It went quiet and deep inside its own body, so deep that it was safe and warm even if its feathers were covered in snow.

They showed lots of other stuff too, like mountain goats charging each other and slamming heads together and a wild cat with her baby. But mostly I remember those men with smelly socks laughing in their tents. And the bird all alone out there with its eyes shut in the storm, not moving because there was no other place to go.

If April is the cruelest month, then adolescence is one long April. For many of us, it’s the hardest period of our life and, like all trying periods, the most formative. It’s the time when we most want to conform and blend in with our peers, yet it’s also the one when we’re most acutely self-conscious of our apartness. It’s when we’re most prey to an excess of sensitivity—our individuality appearing to us not as uniqueness but as grotesque Otherness.9 That’s why Tourette’s is a double whammy: it not only augments that sense of being an outsider, but peaks precisely during that period when it takes so little to feel estranged. That feeling, while less overpowering, has stayed with Anthony. “I’ve always felt the story of my life has been about being normal but on the fringes of abnormality, and it’s the fringes that separate my history from the rest.”

Once Tourette’s came on full force in junior high, Anthony began isolating himself, spending his free time engrossed in books and video games. His heart no longer in competing, his performances dropped off. His mother eventually let him take a break from competitions so long as he kept attending practices. It would prove to be a three-year burnout, prefiguring the exodus that followed his Olympic success. His tendency to withdraw when upset would remain with him, also manifesting on a micro level: to this day, distress can cause him to shut down even in the presence of others into a kind of human sleep mode, a cocoon-like refuge against interaction with the outside world.

Junior high was coming to an end. The most prominent high school in the area in athletics and academics, Hart High, wasn’t in their locale, so Sherry appealed to his academic prowess to get him in. Unlike his regional high school, Hart offered AP courses. His club team was in the same district, so for the first time he’d be attending school with his swim team peers. Even so, Anthony initially resisted this because he’d be going to a different high school than his neighborhood friends. But he changed his mind after an incident that took place in a housing subdivision near their neighborhood. One of the houses there had been empty for years, a blight of a structure overrun by weeds, its back window shot out by a BB gun. One afternoon while Anthony was out with a small group of friends, they decided to climb into the house through the broken window.

Tommy climbs in first, then the others. I follow.

We tiptoe. Nothing in the house. Just a few chairs.

“Check it out, an answering machine.” Travis’s voice echoes through the house. He holds the phone up. “Hello, hellooooooo.” He slams it back down. “I guess no one’s home.” The laughter echoes.

We wander through the house, then return to the living room. In the corner is a box of fluorescent lights. Tommy pulls one out and tosses it to Mikey. Then he pulls another for himself and raises it up with two hands like a Jedi Master. “Luke, I am your father.”

Mikey also goes into dueling stance. “I see your Schwartz is as big as mine.” Then he swings. The long bulbs shatter on impact, exploding in a puff of white smoke. Tommy and Mikey jump back. We all go silent, exchanging uncertain glances. Then, out of nowhere, Mikey breaks the silence. With a cry, he grabs a chair and smashes it into the ground repeatedly until it’s in pieces. And then everybody goes apeshit. Tommy charges at the wall with his arms raised, yelling, “Ahhhhhh!” and at the last second slams his leg into it. His foot goes through the plaster all the way to his knee. They’re all yelling and running around, smashing things up and ripping tiles off the kitchen counter. It’s crazy—all this crunching and shattering and breaking and war cries and whooping and bits of plaster and wood and tiles flying all over the place . . . I don’t break anything myself, I just hang back, watching them. But I still egg them on.

“Dude, what about those!” I say, pointing up at the long fluorescent lights in the kitchen.

Travis looks up, eyes gleaming, and then he starts hurling tiles at them. The first misses but the second makes contact and the light explodes, the shards flying through the kitchen in a cloud of white smoke. We huddle for a moment, shielding our faces in our elbows.

“There’s more in the box!” I cry, and we run back to the living room where I watch him smash those.

When one of the boys, Tommy, later learned that the owner was sobbing in front of the house, he turned himself in. The families of each boy involved had to pay thousands in repairs. Anthony was let off because he hadn’t actively participated in the destruction. He talked himself out of getting in trouble (“lying to save my skin was second nature”) but he knew he was guilty through association. The incident became a forewarning of what might come if he didn’t make a change. From then on he resigned himself to moving to the new high school. His older brother Jackie, who’d already left for college, convinced him that swimming could be fun again since he’d be on the same high school team as his club teammates. He also began to think of the new school as an opportunity to start over without the stigma of a neurological disorder, since the medication he was taking suppressed his Tourette’s symptoms. In late 1995, soon after starting at Hart High, his parents sold their Castaic home and moved to a smaller house in the more upscale Valencia, which was closer to the high school.

At Hart, Anthony’s swimming burnout ended. He continued to train at the Canyons Aquatic Club team with Bruce Patmos, a demanding performance-oriented coach whom Ervin acknowledges was a good trainer who got results from his swimmers. But it was his high school coach, Steve Neale, who rekindled his enjoyment of the sport. “If it wasn’t for him I probably wouldn’t have made it to college swimming at all,” Ervin says. “Steve was all about the family of it. He loved the kids.” Beyond that personal, even paternal relationship with his swimmers, Neale also cultivated the sense, even if Anthony didn’t realize it then, that swimming was about more than just performance.

“Not that it was all fun and cookies,” Neale told me. “But swimming has to have a value and purpose. It has to be meaningful.” Anthony and his three teammates—Ryan Parmenter, John Terwilliger, and Eric Reifman—became known as the “Fearsome Freshmen.” The two standouts of the group, Anthony and Ryan, could, between the two of them, win every individual swimming event at high school competitions. Local newspaper clippings from that period with titles like “Hart Pair Making Splash” include photos of Ryan and Anthony posing in the pool with crossed arms (knuckles pressing out on biceps to make them bulge) and the kind of dour don’t-mess-with-me expressions that still seem cool and badass when you’re a teen.

Upon beginning high school, Ryan, John, and Anthony made a vow: All right, boys, we’ll be men soon. Our goal should be to each have a threesome10 before we leave high school. It was not to be, however, for the young idealists. “We were so far off,” Anthony recalls. “Not one of us even lost our virginity in high school.” Despite his swimming fame, Anthony remained introverted and shy, especially around girls. His freshman year he was particularly tongue-tied around the older girls on his swim team, who by then had come to recognize the power of their sexuality and had no qualms about exercising it over the young star swimmer.

I still have at least a half hour before the 100. Lauren and Danielle sit on each side of me on a beach blanket laid out on a grassy area right outside the pool. Their towels are tied around their waists and over their bathing suits.

“Hey, Anthony . . . ” Lauren says.

“Hi, Anthony, what’re you doing?” Danielle says. She’s sitting really close to me and smiling. Just last night she was making faces with spaghetti hanging from each nostril and an orange wedge stuffed between her lips, but now all I notice are how her boobs are squished under the bathing suit.

“Uh, nothing,” I say.

“Oh yeah, nothing?” Lauren says. She scoots over closer to me and puts her hand on my knee. “Nothing at all?” Then Danielle puts her hand on my other knee.

My thighs tense up. “Uhhh, what are you doing?”

“You know what we’re doing,” Danielle says.

“Or more like, you know what you’re going to do,” Lauren says, smirking.

Their fingers are moving along my knee. “Wha—what are you doing?”

Lauren tosses her hair so that her auburn curls fall down over part of her face. “You’re going to rise to the occasion for us.” Her hand starts moving up my leg.

I’m frozen. I shake my head. “No . . . no, I won’t.”

Danielle leans into my ear and whispers, “Oh yes, you will.”

I look down at their hands and gulp, then look straight ahead. From the pool, I hear the whistle blow for the start of a race. The starting signal goes off to a roar of cheers. I don’t look down but I feel their fingers slide along my thigh, slipping under the hem of my board shorts.

“No,” I whisper. My mouth has dried out. But it’s too late, it’s happening. I can feel it happening.

Lauren’s eyes widen as she notices the movement in my lap and she looks over at Danielle. They both start giggling and then run off.

In high school Ervin shifted from backstroke to freestyle—mostly, he claims, because he tired of colliding into lane lines. Though he was the fastest sprint freestyler on the team, his friend Ryan led every practice. Anthony would push off five seconds after Ryan, sprint to catch up, and then hang back and draft off him the rest of the way.11 This isn’t something lead swimmers usually tolerate, since it’s like having a parasite dangling off your toes, but Ryan endured it without complaint for years.

Bruce Patmos’s workouts often consisted of high-intensity sets with plenty of rest, unlike the default high yardage/minimal rest grind that characterizes most club-level practices. This training was ideally suited for Anthony, who improved dramatically with each successive year. As Ryan, who’d been training with Anthony since the age of eight, recalls, “It was junior year when he really started separating himself from the pack and going crazy fast.”

At the biggest regional meet of the year, Anthony qualified for US Nationals in the 200 free, as it was easier to qualify in longer events than in sprints. Though he died in the last 100 yards,12 he went out so fast that he still qualified: he claims he went out in forty-four seconds for the first hundred yards and fifty-three for the second. At the end of the race, he was, as he puts it, “pretty much vertical.” It’s a tactic he’d employ in the future for his 100 sprints: go out like spitfire and then, when the polar bear jumps on his back near the end, hang on in hopes that the others can’t catch him. But this turn-and-burn, fly-and-die tactic does have a downside: it hurts.

Stroke analyst Milton Nelms remembers watching Ervin light it up off the blocks at a college meet only to perish in the final meters: “It was like he was struck by a headhunter’s curare blow dart. But that’s why I love to watch the guy. He doesn’t care. The dude races. We lose that in the sport because everything is so patterned and planned. You rarely get outliers that way, who break free.”

Among the college coaches scoping out potential recruits in the junior class that year was the Cal–Berkeley co–head coach Mike Bottom. When he first saw Anthony race, he knew he was witnessing a pure sprinter’s instinct in action. Even though Anthony didn’t win that particular race, and even though his stroke wasn’t all that great at the time, there was something about how he moved through the water, something about, as Bottom put it, “how he put his hand on the water,” that caught his eye. Other coaches would recruit him, but it was Bottom who pushed the hardest and ensured he was offered a full scholarship. (After meeting Sherry Ervin, he knew it would take a full ride to get him.) Anthony, meanwhile, had no plans to swim in college beyond his first year. He saw swimming as means to an end, as evinced by his quote at the time from a local newspaper article: “I wouldn’t say I really enjoy [swimming], but I know it’s something I need to do. It’s like work to me. I’m out there to get into college.” This sunless and calculated mindset is something he now warns against: “It’s a cliché, but it really is about the journey, not the destination. Using swimming to get to college or a scholarship is a destination. That’s not the right way to think about it.”

As Ervin grew taller and larger, his medication requirements also increased. He was soon up to three pills daily. His Tourette’s symptoms were now somewhat controlled, but at the cost of sedation. He was constantly napping during the day, which then led to nocturnality. His mother would hear him getting online to play video games in the middle of the night (this was back in the laborious and noisy dial-up era when logging on sounded like R2-D2 getting into a car crash). So she would lift and set down the phone receiver, repeatedly. “I wasn’t doing it to be mean,” she says. “I was doing it to force him to fall asleep. Eventually I would wear him down.”

Ervin has never been a conventional sleeper. To this day, perhaps out of some neurological quirk, he can’t sleep in complete darkness. He requires light and sound, preferably the preternatural glow and buzz of a screen. “It’s almost like when you eliminate the stimuli, it becomes a heightened sensation,” he says. “Nothing wakes me up faster than total darkness and silence.”

In high school he started swimming twice a day year-round (previously he only swam doubles over summers), which also contributed to his fatigue. Unable or unwilling to get up on days he had morning practice, Anthony would be dragged out of bed by his mother. After swim practice and before school, he’d take his medication. By the second or third class, when the pill kicked in, he’d often fall asleep. By lunch the medication would wear off and he’d take another pill, leading to lethargy during his afternoon classes. Sleeping in class wasn’t as alienating as the tics, but the regularity with which he drifted off still left him feeling like he was on the periphery of the “normal” high school experience. “The meds almost caused me to become less myself,” he recalls. “Not much of anything, really.”

My eyelids are so heavy. I lift my left foot up and hold it off the ground. That works but I can only do it for so long. I let it drop. I try to just close one eye at a time, but it’s a struggle keeping the other eye open. Mr. Mansfield is writing a formula on the chalkboard. I try to focus on it, but my eye starts fluttering. The scraping of the chalk sounds so far away. So far away . . . I let both eyes close. Just for a little while. Just a little.

Just . . .

. . .

. . .

I raise my head and look around. There’s laughter. Where am I? I don’t recognize anybody. This isn’t my class. Kids I don’t know are grinning at me. Mr. Mansfield is standing over his desk, chuckling. It’s the next class. I slept through the end of my class and he didn’t wake me.

“Don’t worry, Anthony,” Mr. Mansfield says. “Your study hall teacher was notified that you were . . . otherwise preoccupied and would be on your way shortly.”

Everybody starts laughing again. My face is hot.

“Sorry,” I say, and grab my backpack. I try to laugh but a weird sound comes out of my mouth. He smiles and opens the door for me. I walk out, the laughter following me out the door.

I stop and just stand there for a while until my face cools off. Then I walk down the empty hallway toward study hall, trying not to step on any lines.

His first two years in high school, his friends were exclusively swimmers. But as an upperclassman he needed some separation and escape from that world, which incidentally was mostly white. His junior year he met Quincy, a Filipina, who became his best friend. Through her, he made a new posse of friends, among whom he was the only non-Asian. “A couple of them fulfilled a warped form of the ‘model minority,’ acing tests while regularly ditching or sleeping through class,” Ervin recalls. “Otherwise, they probably cared more about break dancing than school. And more about cars and girls than anything.” Something about their laid-back indolence as protest against demanding parents, their outsider status as Asian Americans, and even just their plain friendliness and acceptance of him, Tourette’s and all, appealed to and comforted Anthony. They also may have helped him get in touch with a minority root he didn’t know he needed at the time. But mostly they offered him an alternate community outside of his routine of swimming and family—something he would continue to look for through college and after. One of them, Vouy, cut everyone’s hair, including Anthony’s, in a high tight fade. “J.R., Peter, Ray, George, Jabez, Sandro . . . it was like the black barbershop thing except it was a crew of Asians,” he says.

One day they bought black T-shirts with red nWo logos (a pro wrestling team) from the mall, posed in them for a group photo as a wrestling troupe, then returned the shirts for the refund. Another time they took off in a three-car day-trip caravan for San Diego to challenge a master gamer at the video game Marvel vs. Capcom in a drop-in tournament, “just like karate masters in old Japan might travel to challenge somebody to a fight.” It’s the only trip he recalls from high school that didn’t involve swimming or family.

Throughout high school he associated swimming with straight-laced restraint. Swimmer gatherings consisted of “eight people sitting quietly in a room, drinking punch and eating cake.” It wouldn’t be until his recruiting trip to University of Southern California that he got his first sip of college swimming life.

“Chug it, chug it, chug it, chug it . . . ” Others get in on it. “CHUG IT, CHUG IT!”

I raise the wine cooler to my lips. It’s half full but I don’t lower the bottle until it’s empty. It’s sugary sweet and goes down easy. I slam the empty bottle onto the table. They all start laughing.

My third bottle. Most I’ve ever had. Snoop Dogg is bow-wowing from the speakers. Two guys are holding one dude by the legs upside down over the keg and a crowd is around him chanting out the seconds: “One, two, three, four, five . . . ” He makes it to twelve and then foam starts spilling out of his mouth and over his face until he gags and sputters, spraying beer everywhere. They put him back on his feet, his face red and dripping. He throws his arms up and beats his chest. The next guy goes up and lasts seven seconds and everyone boos. Another guy is slinging his arm around any girl he stumbles upon, pulling her face into his pecs and whispering into her ear. They don’t even seem to care. One girl, after he says something in her ear, even turns to him and squeezes her boobs between her biceps, shaking them back and forth. Her friends start hooting and shouting, “You go, girl, shake those titties!”

What the hell is going on here?

The guy who did the kegstand dry heaves during a game of beer-pong and charges to the balcony. We all watch him through the window as he doubles over the balcony banister and barfs. People throw their arms up, cheering and high-fiving.

Soon people are laughing too loud and too hard over things that aren’t even funny, and the place starts spinning, so I head into one of the bedrooms where there are fewer people. I sit on the bed and start talking to a girl. She keeps leaning in close and her T-shirt falls open, displaying the bright orange of her bra. After a while the others in the room leave and it’s just the two of us. I don’t even know how it happens but we start kissing. I can’t believe it. I’ve only made out with a girl twice before and she was my friend so that was weird and didn’t really count.

I don’t know what to do so we just keep kissing while sitting on the bed. And then she gets up and turns the light off and comes back to me. I can’t believe this is happening . . . Now what? What if she wants to—

And then the door opens and this guy comes in and turns the light on.

“Hey! What the hell? That’s my bed,” he says. He’s got the broad jaw and face of an action figure.

“Don’t worry, it’s cool,” I say.

“What do you mean, Don’t worry, it’s cool? Get off my bed!”

And then, next thing, I’m back out in the noise and harsh fluorescence of the living room and the girl leaves with her friend and my chance is gone.

But the following morning, even though I have a killer headache, I don’t even care because I know I was at a real college party where I made out with a real college chick.

For real.

_________________

7. Fucking pop culture. Return to text

8. The and/or reflects scientific uncertainty. Research now suggests that individuals with Tourette’s don’t have an excess of dopamine production, as previously believed, but rather a supersensitivity of the postsynaptic dopamine receptor sites. Specifics aside, the gist is that the nervous system is jacked up and there’s some serious neural firing going down. Return to text

9. That, at least, was my experience growing up in a rural Maine blue-collar mill town as a shy, bookish, gangly kid with heavily accented immigrant parents and a long foreign name that allowed for all sorts of mocking back-of-the-school-bus adaptations (the worst two being Constantine Stringbean, which played on my insecurity over my daddy longlegs physique, and Constanteenie-Weenie, which I found grossly unwarranted since the girl who coined it had never even seen my weenie). Junior high felt like a three-year trek through a minefield. But if I now try to pinpoint how I was actually victimized, I come up short, which makes me think I was just hypersensitive and insecure and 90 percent of my angst and fear and persecution complex was self-inflicted. It’s representative of what most kids go through, though I probably bottomed out lower on the insecurity spectrum than most. I even told my YMCA swim club coach to call me Chris instead of Constantine, which explains why the bulk of my Y meet ribbons are awarded to Chris Markides. My mother and father, who were the inverse of the Überinvolved stopwatch-in-hand swim parents, had no clue about my alter ego until a run-in with the pool director, in which he shook their hands and congratulated them on Chris’s performance. Return to text

10. Not with each other. Return to text

11. Drafting is when one swimmer tailgates the swimmer in front—fingertips entering the water just inches behind the toes of the lead swimmer—and thus gets pulled forward in the current, or slipstream, created by the lead swimmer. Basically it lets the person in front do the work for you. For a Look, Ma, no hands! illustration of this principle, stand in waist- or chest-high water a few inches behind the head of someone who’s doing a backfloat. Then start walking backward through the water and, presto, the person floating will get sucked into your wake and travel along with you.Return to text

12. To “die” in swimming is standard lingo for describing the state of All Systems Fail at the back end of a race. Unlike the pleasurable la petite mort of an orgasm, this little death brings only the fireworks of pain. Return to text