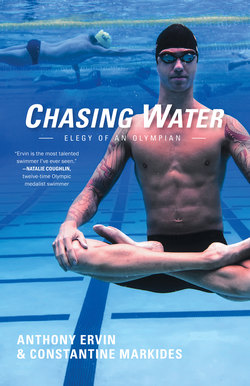

Читать книгу Chasing Water - Anthony Ervin - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1.

The Ready Room

I swear, gentlemen, that to be too conscious is an illness—a real thorough-going illness.

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Notes from Underground

Are you ready for a good time? Are you ready ready ready?

—AC/DC, “Are You Ready”

London Olympics, 50 Free Final, August 2, 2012

The reigning Olympic champion is beating his chest. His hand is cupped, which makes the sound even louder. A few others start doing it too, some sitting, some standing. The chest-slapping echoes through the makeshift room. Does inducing blood flow to these muscle groups really make any difference? Or is this a war cry, a preparatory battle sound? Maybe it’s a confidence boost.

Drop these thoughts. They’re distractions. There’s no room for error in the 50 and distractions lead to error. It is a truth universally acknowledged that an athlete in pursuit of victory must be in want of an empty mind—why is Jane Austen in my head? My thoughts are swinging like monkeys from vine to vine. I try to turn my focus back to my upcoming swim: the start, the breakout, the swim, the finish. It’s a constant tug-of-war, rehearsing my game plan without letting other thoughts interrupt it. If the thoughts come along I try to just recognize them and let them go. Same idea behind meditation.

But I can’t maintain my focus, can’t help but circle back to the chest thumping. César’s pecs are mottled red from the blows. Maybe all the hitting is a cry for attention. I look down at all the tats covering my arms. Who’s to say these aren’t a cry for attention too? Maybe I’ve also inflicted pain on myself to stand out and be noticed. I’ve always talked about them as my way of reclaiming my body after I left the sport, but maybe that’s just me trying to make something noble out of my peacocking.

Races are won and lost in this room before they even begin. It can get intense: some pray, some smack themselves, some try to intimidate their opponents by staring them down. Right now a few guys are bouncing on the balls of their feet, pummeling and kneading their muscles, shaking their dangling arms. A couple are praying and murmuring to themselves. I’m sitting perfectly still—ironic, because my mind is all over the place. How’d I get here again? It’s been twelve years and I’m back in the ready room of the 50 free Olympic final. In a few minutes, I’ll once again vie with seven other swimmers for the title of fastest swimmer in the world.

In this room, the ready room, time is compressed, magnifying my isolation. There are almost no familiar faces this time—no Bart Kizierowski, no Gary Hall Jr. But there is Roland Schoeman, who’s older even than I and still in the game. I first swam against him freshman year of college and we’ve been friends since. A knowing look passes between us. A fiber also connects me to the people I care about who are in the stands right now, who’ve flown across an ocean to watch me. I try to shake off the pressure of their expectations and redirect my attention to my start.

But that only makes things worse. My start in yesterday’s semifinal is still a radiating, pulsing memory. It’s so raw even my muscles and nerves remember it. When the starting signal went off, I pulled on the block too hard, causing a subluxation of my shoulder. I left the block in a bolt of panic and hyper-awareness. I’ve only felt adrenaline like that once before, when I almost died while running from the police. In the adrenaline rush time slows down. It gave me the space to yank my arm while in the air, causing my shoulder to suck back into place as I entered the water. But I recovered and the rest of the race fell into place perfectly. I caught up, placing third and making the finals heat. Fortuna may have shone down on me then, but I can’t afford another start like that.

There’s a roar from the crowd. We’re up. This is no time for self-doubt. We stand in file and prepare to make our entrance. It’s far less theatrical here in London than it was at Olympic Trials in Omaha, where the entire stadium was darkened except for spotlights on the lanes. But far from diminishing the occasion’s significance, the austere brightness only makes it stand out more starkly.

Do I belong here, at the world’s premiere swim contest? I do. I’m not one for false modesty. But do I deserve to be here? Probably not. Others have worked harder, sacrificed more. I’m only here because I excel at a stunt, because I’m able to move my body through water for 50 meters faster than others. It’s just a little trick, a well-performed acrobatic. For this I get to be paraded around the world and ogled over. I’m not saving a life or writing a magnum opus or masterminding some epic heist. I’m just sprinting down a pool, like a prize racehorse galloping around a track. And yet a lot of value is imposed on this. For some reason, the world finds this meaningful.

Who am I kidding, playing the blasé intellectual? For months now I’ve been correcting reporters for labeling my return to swimming a “comeback,” telling them I’m just here to enjoy the journey, to regain a love of the sport. Which is true. And bullshit. As much as I hate to admit it, I want to win. I know it in my overcharged nerves. I was just trying to trick myself into thinking I didn’t want it. It was my way of keeping the pressure off. But here, at the worst possible time, I recognize it, feel overwhelmed by it. I’m trapped by my own ploy.

It’s time. The announcer calls us out one by one. Even through my headphones I can hear the crowd. The memory of my shoulder is hovering over me as I step out onto the stage.

I’m not ready.

On January 14, 2012, a mere seven months before the London Olympics, an unexpected figure stepped up to the blocks at the Austin Grand Prix as the fastest qualifier in the 50-meter freestyle. At 6'3" and 170 pounds, he was the smallest among towering competitors—a cadre of the fastest sprinters in the US—and, with tattoo sleeves, also the most heavily inked. The Universal Sports commentator Paul Sunderland identified him to the viewers at home: “Anthony Ervin. And what an interesting story this is. Tied for the Olympic gold medal at the [2000] Sydney Olympic Games with Gary Hall Jr. and then has had, to put it mil—” he stopped himself, “some difficulties, let’s just put it that way, and has come back to swimming.”

“You know why I love this story, and this is a tremendous story,” interjected the other commentator, three-time Olympic gold medalist Rowdy Gaines. “This guy now can retire from swimming in a good way. He’s going to be happy about it. And he wasn’t happy when it happened the first time.”

It was odd to hear talk about Ervin retiring again. There wasn’t really anything to retire from yet. Except for some halfhearted, abortive attempts to work out, he had only returned to serious training the previous year after eight wayward years. During that time he had purged swimming from his life, including his Olympic gold medal, which he auctioned off on eBay in 2005, donating the $17,100 proceeds to the UNICEF tsunami relief fund. His return to the pool was motivated more out of a need for psychic rehab than any desire for a comeback. But by the end of that sunny January day in Austin, the thirty-year-old found himself in the unlikely position of being the second fastest American sprinter.

* * *

When I first met Anthony Ervin, he was sitting in the bleachers of a Brooklyn pool, reading The Professor and the Madman. He had a gaunt-English-major-turned-tattooed-indie-hipster vibe going. The kind of guy you might find behind the counter in a record store or tattoo parlor on Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue. Not the type you expect to encounter in a swim school, except maybe in New York City.

In short, I thought I had him all figured out. It was early 2009 and I’d just moved to New York from London. A former college swimming teammate had hooked me up as a part-time swim instructor with Imagine Swimming, a thriving swim school that boasted a hip roster of instructors with elite swim pedigrees or—in keeping with the program’s ethos—artistic/creative backgrounds. It was my first day on the job, so when I arrived and saw him reading on the pool bleacher, sporting a bushy goatee, I figured he fell under Imagine’s creative camp.

I went over to him. “Good book. Have you got to the penis part yet?”

He looked at me askance, as if appraising whether or not he should respond. “There’s a penis part?” he said finally.

“You’ll know when you get to it. Hard to forget.”

He shrugged. I couldn’t tell if he was amused or being dismissive.

“I’m Constantine, by the way.”

He paused. “Tony,” he finally said, and returned to the reading.

As I was getting my cap and goggles, the shift supervisor approached me. “So, I see you met Tony,” he said. “You’ll be coaching with him after lessons.” This was unexpected. Not all Imagine instructors have competitive experience, but the coaches do, and often at the sport’s highest echelons. With him? I scoffed to myself. Perhaps he had the ideal creative spirit for working with three-year-olds, but was he qualified to coach? He probably swam freestyle with the earnest low-elbowed chicken-wing stroke one finds at YMCA lap swims.

“Really?” I said, trying to keep the smugness out of my voice. “Did that dude ever swim?”

There was a pause. “Yeah, you could say that. He was the fastest swimmer on the planet for two years.”

* * *

Over the next few months, we got to know each other. He had the engaged, nervy presence of someone who’s had too many cups of coffee, as well as a caustic wit, sharp tongue, and lack of any self-censoring mechanism, which made him come across as more New Yorker than California native. We rarely talked about swimming, but sharing an aquatic history no doubt buttressed our friendship. Though I had dropped out of competitive swimming much earlier than he (sophomore year in college), and though I had been a big fish only in the smallest of puddles (high school state champ in Maine, a state where, with rare exceptions, the only swimmers famed beyond its borders are crustaceans), we had both left the pool to front life on our own terms, taking divergent paths that led into literary territories. As a writer who, for better or worse, had always felt uncomfortable within writer communities and rebelled against its circles and programs, I could relate, at least inversely, to Ervin’s rejection of hypermasculine sports culture. I had spent more time among lobstermen and carpenters than around writers, so it was only natural for Anthony’s unconventional merging of physicality with analytic bookishness to resonate with me. He was intrigued by my compulsion to write and I was intrigued by his rebuff of the golden platter. And what a golden platter it was.

* * *

The 50-meter freestyle sprint—one length down an Olympic-sized pool—is swimming’s glory event, the aquatic equivalent of the 100-meter dash. The world champion can boast, as could the Jamaican runner Usain Bolt after the Beijing Olympics, of being the fastest human on earth. The compound word freestyle is meant literally: any technique is permitted, even doggy paddle, corkscrew, or double-armed backstroke. Freestyle is synonymous with front crawl, the default stroke in any freestyle race, only because it’s the fastest way to swim across the water’s surface.

Though Michael Phelps is heralded as the most dominant swimmer in the history of the sport, he isn’t the fastest sprinter in history, or even of his era. If he were, he wouldn’t dominate as many events as he does. The 50-meter sprinter is a different species of creature, more cheetah than antelope, built and bred for stupendous but short-lived speed. Genetic marvels of nerves and fast-twitch muscle fibers, few can maintain their top speeds for much more than the twenty-something seconds that the event lasts. The current men’s world record, held by Brazilian César Cielo, is 20.91 seconds. He swam this Herculean time in 2009 during the two-year stretch when “tech suits” were foolishly allowed in competition, thus leading to the subsequent shattering of practically every world record.1 While purebred sprinters also often reign at the 100-meter sprint—the distance where one first starts to cross into the vast estate of Phelps’s watery kingdom—their high-RPM engines seize up when revved over longer distances.

Ervin belongs unambiguously to the cheetah camp of swimmers. USA Swimming and FINA announcer Michael Poropat once called him “possibly the most naturally gifted sprinter in swimming history.” But when Ervin was nineteen and stepped up to the blocks in the Sydney Olympics, the buzz wasn’t about his speed. It was about his race. With a Jewish mother and black father, he found himself branded as “the first African American swimmer to make the Olympic team.” It was a confusing label as he’d never viewed himself through the lens of race.

Ervin’s gifts, like his heritage, are unconventional: less physical than abstract, less about power than finesse, as much about cognizance as natural ability. After so many years of shunning competition, his return to swimming had reignited his competitive streak. But he was wary of this renewed impulse to win. To even express hesitation over one’s competitive drive is a rarity among athletes. Even the most easygoing tend to be fiercely competitive. Some would even say that competition is to athletes what creativity is to artists: without it they’re stagnant. Competition, after all, invigorates. Though often viewed with disdain or skepticism by the intelligentsia, athletic fervor is more than a predictable by-product of cutthroat capitalism or team spirit jingoism. The absurd particularity of any sport—whether it involves running around and slapping a hollow yellow rubber ball back and forth over a net, or running around and kicking a bigger ball into a bigger net, or even just running around—is simply the incidental stage upon which the passion and physical artistry play out, a clash of wills that rejuvenates both participants and spectators.

But at the same time, competition also favors antagonism over cooperation and necessarily entails winners and losers. Reconciling his zeal to win with his ambivalence over the nature of competition itself is one of the many ways Ervin resists the stereotype of the one-track-minded athlete. He brings to his swimming the analysis and hyper-self-consciousness of the modern intellectual, a self-awareness that facilitates his speed in water, even if it may undermine him on the starting block. Again and again, Ervin deconstructs the socially defined binaries: thinker vs. jock, black vs. white, rebel vs. role model. If there were such a thing as a postmodern swimmer, he’d be its poster boy.

The established story is that Ervin left swimming because he met his swimming goals and wanted to pursue other interests like music; that he auctioned off his gold medal out of humanitarian impulses. All true enough. But truth is like a matryoshka doll, with dolls nested within dolls: take apart the outer shell and you’re left with a severed façade and a deeper truth. His athletic efforts may have transpired under spotlights, but deeper struggles unfolded in isolation. Medals, titles, and records may bestow fame, but a short-lived one; athletes are doomed earlier than most to the fate of time-ravaged Ozymandias. As A.E. Housman wrote in “To An Athlete Dying Young”:

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

Or as Charles Bukowski more bluntly put it:

being an athlete grown old

is one of the cruelest of fates . . .

now the telephone doesn’t ring,

the young girls are gone,

the party is over.

By discarding the laurel, Anthony Ervin preempted destiny, cheating it of its cruel withering hand. As with Andre Agassi, another gifted athlete who resented his sport for most of his career, Ervin stands outside the archetype of the driven, striving champion. His story is interesting not for what he achieved and lost, but for what he rejected and rediscovered.

Waiting behind my block before the race, I’m an automaton, body and mind on cruise control. The entire process is ritualized and rote—walking out in line, sitting down, removing the uniform and headphones, standing up, taking deep breaths—every aspect programmed to keep all distractive thought at bay. The official’s whistle calls us up to the blocks. The crowd is loud. I bend down, arms hanging, poised to clutch the block. There are a few final cries and exhortations before it finally goes silent.

“Take your mark” rings out. I hunch down, gripping the block. But I’m unable to obey the simple command of those three words, unable to take my mark, or at least stay on it. Instead I’m off balance, swaying. For whatever reason, I can’t keep my energy coiled and find myself falling forward. It’s a slight movement, but it’s enough. The starter holds the signal for longer than usual. I pull my body weight backward, trying to offset my forward momentum. Just as I lean back, the starting signal goes off. Maybe the official was waiting for me to stop moving. Or maybe someone else took awhile to come down. Who knows.

We all dive off the block, but not at the same time. The seven of them dive and I follow. I’m last off the block, last by a lot, still airborne when the others are already underwater. I was hoping that by some miracle I’d have a great start, one that might put me in favorable position for gold. That miracle doesn’t come. But this time I can’t blame it on my Achilles shoulder. There’s no dislocation, no shockwave of adrenaline in midflight, no need to pop my shoulder back into socket. There’s only the awareness that I had a terrible start.

When I surface, over half a body length behind the others, I do the one thing I know how to do. Or rather the one thing that comes naturally to me. It’s less something I do than a feeling I search for, one of continuous acceleration, a feeling not of fast but faster. It’s the essence of how I train and race. It’s something like what opium addicts refer to as chasing the dragon, the desperate quest for that elusive and irreproducible first high. Except in my case, it’s not a high I’m chasing but a fluid connection. And the vessel isn’t opium but water.

I put my head down and swim.

_________________

1. By reducing drag and increasing buoyancy, tech suits turned humans into hydrofoils, especially in sprints. They were swiftly banned. But by then the damage was done, both to the record books as well as to all the swimmers not around for that two-year tech suit bonanza. Return to text