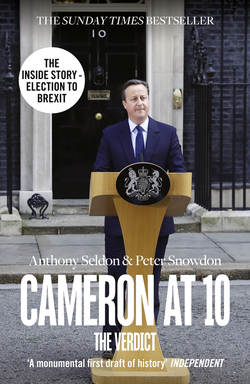

Читать книгу Cameron at 10: From Election to Brexit - Anthony Seldon - Страница 25

Bloody Sunday Statement

Оглавление15 June 2010

Tuesday 15 June, just five weeks into the premiership, sees Cameron’s first major test of his statesmanship, and of his oratory. It comes on unfamiliar territory. The premierships of his three predecessors, John Major, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown, had been deeply embroiled in the affairs of Northern Ireland. While welcoming the progress that had been made, and taking a great interest in Northern Irish affairs, Cameron is keen to avoid the Province dominating his premiership, preferring to let his Secretary of State take the lead. He is anxious to see politics in Northern Ireland move on, beyond the Blair/Brown era when prime ministers had ‘to spend hours in crisis talks with Northern Ireland politicians, making endless visits, or staying up all night in country house retreats hammering out the latest deals’.1 Besides, relations with Northern Ireland had been changing. From 1972 to 2007, the Northern Ireland Secretary effectively acted as the prime minister of Northern Ireland. But in 2007, thanks to the work principally of Blair, devolution to Stormont was restored. The Northern Ireland Office (NIO) retained oversight of national security, policing and justice. The latter two areas were ceded in April 2010, in the dying days of Brown’s premiership. A devolved assembly in Belfast, with local ministers running affairs, meant Cameron’s wish was likely to come true – assuming the Stormont institutions remained stable and there were no further terrorist outrages. He had mentioned Northern Ireland in just one of his five annual party conference speeches as Opposition leader, in 2008, and then only in passing.

‘When it comes to the union with Northern Ireland, I am very much a traditional Conservative,’ he remarked during those years. He has little interest, still less patience, in the antics of those who emphasise sectarian divisions. What he wants ideally is for Northern Ireland politics to be reintegrated into mainland Britain, believing that a continuation of their own party system in Northern Ireland has disenfranchised voters in the province from full participation in British political life. In an effort to normalise politics in the province, Cameron agreed an electoral pact between the Conservatives and the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) ahead of the 2010 general election. The pact failed to deliver any seats, not least because of the Democratic Unionist Party’s (DUP) success in replacing the UUP as the major unionist force in Northern Ireland.

One major piece of unfinished business remains in Northern Ireland. In 1998, Tony Blair had announced an inquiry into the still controversial events of Bloody Sunday which had occurred on 30 January 1972, when twenty-six protestors and bystanders were shot by British Army soldiers, half of them fatally. The inquiry was under the chairmanship of Lord Saville: a tribunal at the time of the shooting had been discredited as a whitewash. Publication was delayed until after the 2010 general election. Officials in the NIO are now concerned that the new government will bin the report because Labour set up Saville, and Conservatives have been critical of its length and cost. ‘What are you going to do with Saville?’ officials ask nervously of Owen Paterson on his first day as Secretary of State. ‘We will publish it in good order, as rapidly as we possibly can,’ Paterson replies.2 Cameron had been impressed with how Paterson, who was on the right of the party, forged good relationships on all sides in the Province as shadow Secretary. Nevertheless, the republican community in Northern Ireland have a wealth of negative impressions about the Conservatives, and dread their return to power. They believe it will be hard for a Conservative government to admit that the republican community had been wronged.

Cameron knows how much hangs on his response. He discusses Saville’s inquiry with his foreign affairs private secretary Tom Fletcher on 20 May on his first trip to Northern Ireland to see the party leaders. The visit is uncontroversial. ‘Belfast pretty solid,’ records Fletcher in his diary.3 A week later, Cameron hosts a garden party in Downing Street to thank CCHQ staff who had helped on the general election. The imminent Saville Report is much in the air. Cameron walks over to Jonathan Caine, a trusted special adviser whom he and Llewellyn had embedded in the NIO. ‘I think I’ll have to make an apology, don’t you?’ Cameron confides to Caine. ‘I think you will. What is important is how you frame that apology,’ the adviser replies.4 There is another potential problem. The Ministry of Defence (MoD) are wary that the Defence Secretary, Liam Fox, no friend or ally of Cameron’s, might seek to appease the right wing of the party. Fletcher requests guidance from the MoD on their likely response to Saville. They indicate that they will not brook anything that sounds like an apology. Fox is emphatic on this point at a meeting with officials two weeks before publication. Number 10 signals back to the MoD that the prime minister will be standing his ground.

Three weeks pass, during much of which Cameron is busy on the economy and domestic policy. At 3.30 p.m. on 14 June, ten copies of the Saville Report arrive at the NIO, then housed at Millbank on the north bank of the Thames. The summary alone is crystal clear: every single person shot had been unarmed, and the killings were unjustified.5 It is a lot to take in: it is the first time that anyone outside Saville’s own team have seen the report, with the exception of the lawyers who have been through each page with a fine-toothed comb looking for national security concerns. NIO officials divide it up into sections to read it over and prepare the government’s response, working out the possible questions that will demand precise answers. At 4.30 p.m., the full report and summary arrive at Downing Street. Cameron is just off a plane from his first visit as PM to Afghanistan. He already has one fight on his hands with the MoD over bringing British troops home. He picks up the summary.

Cameron reads it sitting on his chair next to the fireplace in his still new office. He is very quiet and seems lost in thought. ‘This is the most shocking report I have ever seen,’ he tells aides. He wants to give nothing less than a full apology.6 At 6 p.m., he convenes a meeting for those most directly concerned. Present are Paterson accompanied by Caine, Nick Clegg, Ed Llewellyn, Fox, Attorney General Dominic Grieve, and the chief of the general staff, David Richards. Cameron picks up the summary off the table and throws it dramatically back down again: ‘I’ve just read this twice. It’s the worst thing I’ve ever read and I’m going to tell you exactly what I’m going to do about it.’ He proceeds to tell his hushed audience the gist of what he wants to say in his parliamentary statement the following afternoon, the tenor of which remains unchanged. Those present murmur agreement, even Richards, a surprise to Cameron’s aides. As Britain’s army chief, they had anticipated more resistance, though even Richards is comfortable with the apology being unequivocal. Cameron reassures Richards that he is aware of the nuances of this, and how the apology must avoid denigrating the record of service by British forces in Northern Ireland throughout the decades of the Troubles – a point that Paterson also makes. ‘We can’t let Bloody Sunday be the defining point of the entire Operation Banner,’ says Caine, referring to the code name given to the British military operation in Northern Ireland between 1969 and 2007.7 ‘Hear, hear,’ responds Richards, very audibly. The MoD’s preference for a more nuanced response is, Cameron makes clear, not an option. Fox sees the way the wind is blowing, and decides against opposing the prime minister’s settled will.

Cameron’s speechwriters, Ameet Gill and Tim Kiddell, are frantically taking notes while Cameron has been speaking. The meeting breaks up and Gill and Kiddell work to turn Cameron’s off-the-cuff words into a formal speech, complemented by drafts from the NIO and Cabinet Office. They sit around Kiddell’s screen, joined by Caine and Simon Case, another official, working until midnight producing a draft speech for Cameron to deliver the following day which they put in the PM’s overnight box.

Cameron rises as usual soon after 5 a.m., finds their draft but makes relatively few comments on it. At 7.30, Paterson and Caine come into Downing Street to discuss final tuning of the speech. They have little to contribute because Cameron is so clear on what he wants to say. At 9.00, Tom Strathclyde, Leader of the House of Lords, comes in for a briefing as he will be speaking on the government’s response in the Upper House. At noon, Cameron leaves for the Commons. He reads through the speech once more before asking for his Commons office to be cleared: ‘I want to go through it on my own to give it one final polish.’ He strikes observers as more than usually calm, confident and focused.8 In Londonderry (or Derry as it is known by nationalists and republicans), where Bloody Sunday occurred, many expect the worst, believing Cameron will seek to make excuses. Crowds gather outside the Guildhall in the city, where relatives of those who died have been invited to read the report. A giant TV screen outside will broadcast live Cameron’s statement in the House of Commons. The long wait is over. At 3.30 p.m., on the dot, the prime minister rises in the chamber:

Mr Speaker, I am deeply patriotic. I never want to believe anything bad about our country. I never want to call into question the behaviour of our soldiers and our army, who I believe to be the finest in the world … But the conclusions of this report are absolutely clear. There is no doubt, there is nothing equivocal, there are no ambiguities. What happened on Bloody Sunday was both unjustified and unjustifiable. It was wrong … In the words of Lord Saville, what happened on Bloody Sunday strengthened the Provisional IRA, increased nationalist resentment and hostility towards the army and exacerbated the violent conflict of the years that followed. Bloody Sunday was a tragedy for the bereaved and the wounded and a catastrophe for the people of Northern Ireland.9

Cameron will not make a better-received speech over the next five years in the House. In Derry, the crowds applaud and there is cheering. ‘Last Tuesday was an unforgettable day,’ writes Edward Daly, the priest who attended to the dying on Bloody Sunday. ‘The great dignity of the families, the immense power and magnanimity of the prime minister’s speech, the international media presence, the brilliantly sunlit afternoon, the ringing declaration of innocence of each and every victim and the minute of silence for all the victims of the past thirty years all added to the wonderful emergence of the truth after such a long time.’10 Even that morning it seemed inconceivable that a Derry crowd could respond positively to a Tory PM. In fact, security arrangements are made to ensure that officials could escape from the Guildhall should the atmosphere turn ugly. Julian King, British ambassador in Dublin, is profoundly struck and moved by the reception on both sides of the border in Ireland. The statement from Cameron so early in the life of the government sets the context for the British government’s relations with Dublin and Belfast for the years that follow.11 It paves the way for the Queen’s historic visit to Dublin in May 2011, the first by a British monarch since Ireland broke away from Britain in 1921, and for the Irish president’s return visit in April 2014.

It is not all plain sailing. On 1 October 2011, Cameron experiences an unpleasant personal encounter in Downing Street. The controversy surrounding the death of Pat Finucane, a Belfast solicitor murdered in 1989 by loyalist paramilitaries who had been colluding with British security forces, was left for Cameron to deal with following the previous Labour government’s unfulfilled commitment to hold a public inquiry. Finucane’s widow, Geraldine, and her family are demanding a fully independent inquiry into the whole episode, something which has the support of the republicans and all parties in the Republic, but is opposed by unionists. The government thinks a review by a senior QC will establish the truth of what happened more effectively and speedily than a statutory inquiry. The review itself would be entirely independent. The family are not convinced by this: so Cameron takes a personal decision to invite Mrs Finucane into Downing Street. He knows the meeting will not be easy. He sees her, one of her sons, a lawyer, and Pat Finucane’s two brothers in the white drawing room on the first floor. Paterson, Caine and two other officials are also present. From the very beginning, it is clear she is in no mood to be mollified; Cameron tells her ‘I know you have no reason to trust or believe me, but I think that a statutory inquiry is neither right nor necessary. It will take years and be bitterly fought over. But there is someone I know who can get to the truth for you far more quickly.’ While Mrs Finucane is extremely disappointed, she remains dignified throughout. At one point the officials believe that one of Finucane’s brothers is about to thump Cameron. Sensing the tension in the room, Cameron draws the meeting to a swift close. Mrs Finucane then storms out of Downing Street to the waiting press outside, telling them that she is so angry she can hardly speak. ‘All of us are very upset and disappointed,’ she exclaims.12

Northern Ireland continues to simmer throughout the next five years, with violence never far away, and political difficulties after the failed talks in 2013 led by the American diplomat Richard Haass, which tries to resolve disputes over the use of flags, parades and other ‘legacy’ issues associated with the Troubles. Many both north and south of the border, as well as in London, are disappointed that the government didn’t build more on the momentum and goodwill of the Bloody Sunday statement to settle outstanding issues. Progress is made with the Stormont House Agreement in December 2014, following cross-party talks initiated by Theresa Villiers, Paterson’s successor as Secretary of State. A crisis is averted over Stormont’s budget and some consensus emerges on dealing with the sensitive legacy issues.

Cameron’s Bloody Sunday response remains his defining moment concerning Northern Ireland. It sees him at his best, instinctive, courageous, fired with moral zeal. Here, his pugnacity does not land him in trouble, as it would later do periodically. The tone of the speech and the words, unusually for a prime minister, are almost entirely his own. ‘It wasn’t my first opportunity to speak on Northern Ireland. It was my first opportunity to be prime minister,’ he said shortly afterwards. He might have favoured similar openness on Iraq, but he deemed it inappropriate to intervene while the long-awaited Chilcot Inquiry was still deliberating. But he could press ahead on Britain’s other twenty-first-century war: Afghanistan.