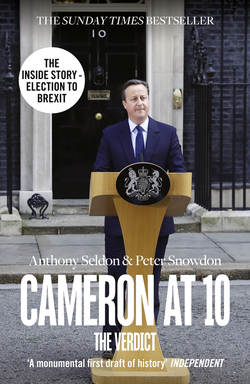

Читать книгу Cameron at 10: From Election to Brexit - Anthony Seldon - Страница 34

Coulson Departure

ОглавлениеMay 2010–February 2011

‘Yes, yes, yes!’ It is Saturday 25 September 2010 and George Osborne is on his knees. He is fixated on the television screen, in the company of Cameron and Andy Coulson. It isn’t positive news of the latest quarterly figures that has brought him to this position. It is something that he knows will have a much greater bearing on the outcome of the 2015 election. Ed Miliband is announced leader of the Labour Party, beating brother David by only just over 1% of the vote (50.65% to 49.35%), and Cameron’s team are fizzing with excitement. For the first three rounds of counting, David was ahead of his brother, but in the fourth and final ballot Ed edged over the 50% mark required for overall victory. While David is supported by most Labour MPs and constituency parties, Ed has secured the backing of the trade unions, sufficient to tip the balance in his favour. Cameron and Osborne fear David. They don’t fear Ed. Cameron agrees with his ultra-political strategist-in-chief. ‘Ed will be a thousand times better for the Conservatives,’ he says. Ed Miliband will take Labour more in the direction of Gordon Brown’s failed policies and he is ‘much less confident’ than his brother, he thinks – not that he knows either brother well.

The news plays into their hands at the party conference in Birmingham the following week, the first for fourteen years in which they have been in power. Cameron’s team had sought to undermine Labour’s conference by arguing that when the party was in power, it had brought the country to its knees with its spending and borrowing. Now that Ed, a principal architect of that strategy, is the leader, it is a much more telling line of attack.

The Tories start arriving in Birmingham in high spirits. They cheer to the rafters when Osborne announces a benefit cap of £500 per week per household.1 Boris Johnson, always a conference favourite, further whips up the delegates when he announces he will run for re-election as London mayor in 2012. David Cameron delivers a feel-good speech, light on policy commitments. It is not the product of intensive preparation as his conference speeches are to be later. Cameron and Osborne have piloted the party into government, are sorting out the national finances, and are overseeing a frantic pace of domestic reform. For all the early criticism of Plan A and the pain likely to be endured, the novelty of coalition government has not yet worn off in the public’s mind. But the storm clouds are gathering. Cameron and Osborne are about to reveal how naive and inexperienced they both still can be.

In late 2006, one year into Cameron’s leadership of the party, they were not getting their message across and concluded they needed a dynamic head of press. Rupert Murdoch was far from impressed with Cameron at the time, considering him little more than ‘a PR guy’. Conscious of their upper-middle-class backgrounds, Cameron and Osborne searched for a ballsy figure with the common touch to project their modernising message more effectively to the country at large. They were not inundated with contenders. Enter Andy Coulson. On 26 January 2007, he had resigned as editor of the News of the World, denying all personal knowledge of phone hacking but taking responsibility for it having occurred under his watch as editor.2 Osborne had got to know Coulson, while Cameron had met him a few times when Coulson was still editor. It was Osborne who first identified Coulson as a candidate for the new role of director of communications. When Osborne met him to float the idea, he was quickly convinced that the former tabloid editor could give them the populist edge they needed to take the fight to Labour.

Coulson met Cameron in his Norman Shaw South office in the spring of 2007. Cameron talked about the job and liked what Coulson had to say: he asked about the hacking concern, and Coulson reassured him about his own role in the affair. Cameron did not probe him deeply, anxious perhaps not to frighten him off, and avoided asking the most searching questions. Coulson subsequently saw Steve Hilton and then Francis Maude and Ed Llewellyn together. Later that spring, Cameron phoned Coulson while on holiday in Cornwall. Coulson again reassured him he knew nothing of the antics of Clive Goodman, the News of the World’s royal reporter who had been convicted of phone hacking.3 That was the green light Cameron needed. At the end of May, Coulson’s appointment was announced.

The first two years went smoothly. Coulson was rigorously professional, and his skill at bringing discipline to the relationship between the Conservative leadership and the media was prized highly by Cameron’s team. ‘What was there not to like,’ one insider said, ‘his understanding of the media was brilliant. He proved much stronger at broadcasting than people thought. He was from Essex. He had edited a red top and had a sophisticated political brain.’ Coulson began rapidly to secure much better headlines for the Conservatives, and for a time all was relatively calm. He achieved the ultimate accolade of admission to the inner circle of Osborne, Llewellyn, Hilton and Kate Fall.

The Guardian had been engaged in a long investigation into phone hacking, and refused to let the matter rest. Hot in pursuit also were two Labour MPs, Tom Watson and Chris Bryant. In July 2009, the Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee summoned Coulson to appear before it to investigate phone hacking. Again Coulson denied any knowledge. The committee concluded, however, that it was ‘inconceivable’ that News of the World executives had not known about phone hacking, accusing them of suffering from ‘collective amnesia’.4

Cameron felt that Coulson was being unfairly victimised, and on 9 July said: ‘I believe in giving people a second chance.’5 He considered that Coulson had already paid for any errors or oversights when he lost the editorship of a high-profile paper, and said he believed that the attacks were politically motivated. Murdoch had slowly begun to approve of the direction Cameron was leading the Conservative Party in, and during the Labour Party conference in late September 2009, with Labour probably at its lowest point since the night of the 1992 election, the Sun announced that it would be supporting the Conservatives at the upcoming general election, having supported Labour for the previous twelve years and three general elections.

However, concerns about Coulson refused to go away. In early 2010, the Guardian reported that Coulson had employed a private detective who had been jailed for conspiracy.6 The paper then followed up with calls to Steve Hilton, but it is unclear whether Hilton informed Cameron himself.7 Representations came into Number 10, reportedly from Buckingham Palace and the upper echelons of Whitehall, questioning the suitability of Coulson moving into Number 10 as director of communications, if the general election was won. Clegg was another who counselled restraint in appointing him, while Paddy Ashdown, Clegg’s mentor, went further, later saying, ‘I warned Number 10 within days of the election that they would suffer terrible damage if they did not get rid of Coulson, when these things came out, as it was inevitable they would.’8

Even Coulson himself told Cameron that he would be happy to call it a day and not join the premiership team. His suggestion was ignored. Cameron and Osborne were contemplating taking on the biggest challenge of their lives, running the country, and they were in no mood to jettison their worldly press adviser on the threshold of power. Coulson duly moved across into Number 10, to the surprise of some inside and outside the Conservative Party.

His first few months at Number 10 belie the concerns and appear only to confirm Cameron’s and Osborne’s judgement in sticking by their man. Coulson sets up camp in Number 12, in the same space where Brown had based himself alongside his media outfit and other chief aides. Coulson establishes strong and good relations with all media outlets, and imposes a calm and reassured regime within Downing Street. He pivots the day around two meetings: at 8 a.m., half an hour before the PM’s morning meeting with the core members of the Number 10 team, including Jeremy Heywood and George Osborne; and at 5 p.m., after the even more important 4 p.m. meeting, when further key decisions are taken. He swiftly builds a strong relationship with Jonny Oates from the Lib Dems, whom he appoints as his deputy, and Lena Pietsch who subsequently replaces Oates when Oates becomes Clegg’s chief of staff. Remaining sceptics are won over by Coulson’s professionalism and personal consideration: ‘He was very well liked, doing things people don’t normally do in that world like buying people presents,’ says an aide. Relations remain fiery with Hilton, a hangover from their long and bitter disputes in Opposition. But this relationship is an exception to the rule. Civil servants remaining in Downing Street through the transition come to see his considerable strengths. It is Coulson’s recommendation that the savvy Treasury official Steve Field becomes the PM’s official spokesman – a successful appointment.

But rumblings about him refuse to go away. On 1 September, the New York Times publishes on its website a lengthy account of phone hacking at News International claiming that Coulson himself had known about it.9 This is dynamite. His appointment to Number 10 is beginning to fail the ‘smell test’. Cameron and Osborne dig in further, compounding their earlier lack of rigour in probing Coulson’s knowledge of the affair by refusing to reconsider the wisdom of confirming his appointment. Indeed they feel it would appear weak to cut him loose in the absence of direct evidence linking him to the scandal. They hope that the noise will simply go away. It doesn’t.

The weeks following the party conference in Birmingham see Coulson’s reputation go into free fall. Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell worries that Cameron is not wanting to face up to the issue, nor to probe further into the truth of the allegations. Nor is he happy with Coulson saying that he will quit if it becomes too big a distraction: this is an admission of guilt, he believes, and tells Cameron so. Cameron still holds his ground: he appointed Coulson on the basis of what he knew at the time, and he will not now abandon him to satisfy those trying to prise him out. To do so, he says, would be to show weakness to his many enemies. He hasn’t even been charged with any crime, Cameron maintains, let alone been convicted. Internally, though, the unity of Cameron’s court is beginning to fracture. Hilton has begun to think he should go: Osborne, Fall and aide Gabby Bertin think he should stay. ‘Our whole stance was not to question what Andy said, but to accept his validation and to defend it,’ says one of them. ‘We believed it, because we made ourselves believe it.’ Coulson is willing to stand down. Again Cameron persuades him to stay. Fatally, Coulson accepts.

By December, the pressure becomes almost unsustainable. On the 21st, the Daily Telegraph publishes a transcript of Business Secretary Vince Cable stating that he has ‘declared war’ on Murdoch and will block the proposed takeover of BSkyB by News International’s parent company, News Corp.10 Following the advice of the Treasury solicitor, which stresses the need for impartiality, Cameron strips the Business Secretary of his quasi-legal responsibility for competition and media policy, giving it to Culture Secretary Jeremy Hunt. Suspicion is fuelled that he is protecting the Murdoch group. Ian Edmondson, news editor at the News of the World, is suspended early in the New Year over allegations of phone hacking at the paper in 2005–6.11

By the third week of January 2011, Coulson’s position is untenable. He quits on the 21st, saying, ‘When the spokesman needs a spokesman, it’s time to move on.’12 Cameron is mortified. ‘I’m very sorry that Andy Coulson has decided to resign,’ he announces. ‘Andy has told me that the focus on him was impeding his ability to do his job and was starting to prove a distraction for the government … he can be extremely proud of the role he has played, including for the last eight months in government.’13 Andrew Feldman says, ‘David depended on Andy for so many things. He respected him, and valued his advice deeply.’14 Cameron knows instinctively that his communications director’s departure will give licence to all who resent his leadership to come out into the open, not least the Tory MPs still simmering after the expenses scandal.

Many in Number 10 are devastated to see Coulson go. There are plenty of tears. Not from Hilton, though, who views it as the opportunity for a major push on the Big Society. But he is at one with the rest of Cameron’s team hoping that the boil has finally been lanced, and that they can look forward to a busy spring without further distractions. Yet the press reaction worries them. It is overwhelmingly negative, typified by the Independent, which says: ‘This affair casts serious doubt on the prime minister’s judgement. He saw fit to appoint Mr Coulson as the Conservative Party’s director of communications when the former editor was tarred by association with the phone-hacking scandal. Why would he want such a compromised spokesman? Was he naive enough to believe Mr Coulson’s assurances? Or did he not care about what had taken place? Neither scenario is very comforting.’15 While naivety is certainly the more plausible explanation, there can be no doubt that there was an abject lack of judgement.

Cameron and Osborne move quickly to cover the gap. The search is on for a successor to Coulson. Because of their reluctance until the last minute to see him go, planning for this eventuality has not taken place. Although not his first choice, Coulson suggests Craig Oliver who had run World News at the BBC, as well as editing the Six O’Clock News and News at Ten. Oliver is summoned to Chequers where he talks to Cameron. They get on well. Llewellyn and Osborne approach the BBC’s political editor, Nick Robinson, for his professional views of Oliver: his reference is positive. As the job is partly an official role, Heywood is brought in: he is impressed by Oliver’s experience at running media programmes.

Number 10 communications directors (earlier called ‘press secretaries’) had traditionally come from newspapers – for example, Joe Haines under Wilson, Bernard Ingham under Thatcher, and Alastair Campbell under Blair. Cameron’s team are excited about Oliver’s experience of broadcasting. He arrives with a bang, making it clear that much of Coulson’s operation was out of date. ‘It’s all very old school, very slow and reactive: 1980s mentality,’ he is heard to say. He wants the whole operation shifted towards digital and social media. Regular Thursday slots are arranged for Cameron to talk to regional radio stations from Number 10. He continues with the ‘PM Direct’ meetings, which give Cameron the opportunity to meet and talk to people across the country. Cameron even starts ‘tweeting’.16 There is, however, a downside: handling the media in the wake of the hacking scandal would inevitably create friction. Fiercely loyal to his boss, Oliver takes on the press lobby, making enemies in the process. Not all in Number 10 adapt easily to the new style. They dislike the criticisms of Coulson’s style, and hanker for the man with whom they had worked so closely through good times and bad for four years. It is all new territory for Cameron’s close-knit inner circle. They are initially wary of the new broom, and it takes a full two years to embrace Oliver fully. But by mid-2013, he has earned his spurs, and he achieves a unique feat for a post-2010 addition to Number 10 by being accepted as a respected insider of the Cameron court. He travels regularly on tours with the PM abroad and in the UK, they talk or text several times daily, and he is a regular and influential member of the PM’s 8.30 a.m. and 4 p.m. meetings.

However, partly as a result of the departure of Coulson, morale in Number 10 slumps badly in early 2011. It is the first sustained period of reversal the team has experienced in government, and they are yet to develop resilience. Cameron is under fire from all sides: the economy is not improving, a series of U-turns in January and February, on the sale of forests and cuts in housing benefit, damage confidence in him.17 Suddenly Cameron, and Osborne too, appear at sea and struggling.

Cameron now compounds any errors over Coulson by not distancing himself from Murdoch and the tentacles of the News International empire. He continues to see Rebekah Brooks and her husband Charlie, an old school friend. In May, the Sun asks for his support to reopen the search for lost child Madeleine McCann, which he readily agrees to out of sympathy. But it prompts questions about whether he was ‘pressured’ into giving favours to News International.18 Was it demanding payback for its support at the 2010 general election? Cameron keeps trying to turn the spotlight onto the government’s domestic achievements, but the probing doesn’t go away. A fresh inquiry into the hacking scandal set up in January keeps the issue in the public eye, and Labour MPs Chris Bryant and Tom Watson are gaining traction with their questioning about whether Murdoch’s support was being traded for commercial advantage. In the summer, always a highly charged time at Westminster, Culture Secretary Hunt announces in the House of Commons on 30 June that the government is ready to give the green light to Murdoch’s bid for BSkyB, giving him enormous power over broadcasting.19

However, on 5 July, Murdoch’s hopes of extending his empire are shattered. The Guardian reports that the News of the World had hacked the phone of murdered teenager Milly Dowler, while she was still officially missing. Ed Miliband seizes the moment, ushering in his most vibrant and effective period as leader. He tackles Brooks head on, suggesting she consider her position in the company, and takes aim at News International. Dominoes start falling. On 7 July 2011, News International chairman James Murdoch announces the closure of the News of the World. On 8 July, Coulson is taken into custody on suspicion of conspiring to hack phones and corruption. On 13 July, News Corp withdraws its bid for BSkyB.20 On the same day, Cameron announces that Lord Leveson will head an inquiry into the media. On 15 July, Rebekah Brooks resigns as CEO of News International. Two days later, she too is taken into police custody before being bailed. On 19 July, Rupert and James Murdoch, father and son, as well as Rebekah Brooks, are humbled before the Commons Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee. The nation revels in a rare moment of Schadenfreude at the expense of the Murdoch family.

Following a week of fast-moving developments, Cameron cuts short a visit to South Africa to make an emergency statement on the crisis in the House of Commons on 20 July. He comes the closest yet to making an apology. ‘Of course I regret, and I am extremely sorry about, the furore it has caused,’ he tells MPs. ‘If it turns out that Andy Coulson knew about hacking at the News of the World, he will not only have lied to me, but he will have lied to the police, a select committee and the Press Complaints Commission, and of course perjured himself in a court of law … if it turns out that I have been lied to, that would be the moment for a profound apology.’21 In a test of stamina, he answers 138 questions from MPs after the statement. It is a bruising experience, but he survives.22

When announcing the inquiry a week earlier, Cameron says that the aim is ‘to bring this ugly chapter to a close and ensure that nothing like it can ever happen again’.23 It is a naive hope. The Lib Dems and the Conservatives are not in agreement. Cameron’s team want to stop the inquiry investigating the role of politicians; the Lib Dems do not, and win. Cameron initially resisted setting up any inquiry at all. He had visibly reeled when Craig Oliver told him on 7 July that the News of the World was closing. He goes up to the flat and talks about how to respond with Osborne, Llewellyn, senior aide Oliver Dowden and with Craig Oliver. Heywood has been arguing forcefully that an independent inquiry establishing the facts would be in the prime minister’s own interests. Cameron’s political staff agree, believing it is the only way to draw the sting from Ed Miliband’s ferocious attack. Gove vehemently disagrees. He subsequently briefs the press against Heywood for advocating the inquiry, which to Gove, as a former journalist, is anathema. Cameron knows that an inquiry will be a minefield, but he heeds Heywood’s advice: he has to do something to stop the firestorm gathering around him. ‘Camp Cameron was hanging by a thread,’ recalls a senior figure in Number 10. ‘He had to find a way of getting through this and calming everything down.’ He is under the greatest pressure in his premiership to date by a distance.

Discussions follow over who should chair the inquiry. O’Donnell is one of many to advise against appointing a judge, on the grounds that their investigations go on forever (Saville’s twelve years on Bloody Sunday are still fresh in everyone’s mind). Nevertheless, they land on Lord Justice Leveson because he has gravitas, and is known to be seeking one of the top positions in the judiciary, and is thus unlikely to want to spread out the inquiry too long. The Lib Dems are strongly supportive of the inquiry, and want it conducted in as public a manner as possible. The decision is taken that the inquiry will be televised, adding extra layers of strain on Cameron and Number 10.

Problem over? Those who hoped Coulson’s departure, and announcing the inquiry, would calm the storm are in for a rude shock. Cameron’s woes are only just beginning. Miliband’s tail is up – he knows he has Cameron on the run. Any honeymoon Cameron may have enjoyed with the media is over, as they probe consistently and relentlessly. One of his team offers this interpretation of what is happening: the ‘Telegraph and Mail think Cameron got into bed with News International before the general election, that he fell in love with Rebekah Brooks who persuaded him to appoint Coulson, an act of naivety and folly that led to the setting up of Leveson, which is going to stuff the British press. For that reason, they are giving us hell.’ Their questions rain down on Number 10. Did Hunt break the ministerial code in dealing directly with News Corp over the BSkyB bid? Was Cameron foolish bringing Coulson into Downing Street? What due diligence did he undertake? Had he allowed the Murdoch empire undue influence over him? When his judgement and integrity are called into question, it galls him, and makes him miserable. He has only himself to blame. It is his worst episode in Downing Street.

Cameron projects his anger onto Miliband who he thinks is posturing cynically. His distress reaches new levels when, on 30 April 2012, the Labour leader forces him to the House to answer ‘an urgent question’ about whether Hunt breached the ministerial code in his handling of News Corp’s bid for BSkyB. Speaker John Bercow’s support of Miliband’s action infuriates Cameron: he regards Bercow as biased and currying favour with Labour. Nerves are very frayed. Llewellyn insists the close team avoid any hostile briefing of the press. Heywood’s critics believe he pushed Cameron towards an inquiry, not because it is in the PM’s interests, but because it suits the Civil Service to rein in News International. In truth, Heywood advocated an inquiry because he judged it to be the best way for Cameron to respond to allegations of impropriety.

Cameron’s personal discomfort grows the next month. He endures acute personal humiliation when personal texts he sent Brooks are released, which he sometimes signed off ‘LOL’, mistakenly believing it stood for ‘lots of love’ (rather than ‘laugh out loud’). They are universally and rightly condemned as embarrassing and inappropriate, above all because they are between a prime minister and a senior figure in a highly partisan media outlet. Some of Cameron’s aides became frustrated earlier by his unwillingness to criticise Brooks personally and say publicly that she should stand down. They wonder whether he has learnt the lesson from his misplaced loyalty to Coulson. Cameron is in a terrible place, skewered in a complex web of loyalties and sense of duty. Charlie Brooks is close not only to Cameron but also to Cameron’s brother Alex. ‘Charlie is one of my oldest friends. I’m not going to dump him,’ he tells his team. He has yet to learn it is his duty as prime minister to stand back from any friendships that might compromise him or cloud his judgement.

The most hazardous moment for Cameron is when he is called to give evidence on 14 June 2012 in front of the Leveson Inquiry. He is questioned for nearly six hours. Number 10 had begun to prepare for the appearance in March and much of his time and energy is devoted to it. Tristan Pedelty, an official in the Private Office and a former barrister, pilots him through the evidence. Cameron worries about his memory and whether he overplayed his hand in his written statement to the inquiry: was his memory at fault? He is often prone to fret about the reliability of his memory when unsupported by written documents. He worries about his ability to master so much detail: he describes it as like a marathon PMQs session. He remains acutely embarrassed about the texts to Brooks. But he is sure of his ground with Murdoch, and tells the inquiry he doesn’t believe he overstepped any mark, or has gone any further in his relations with News Corp than Blair and Brown had done. Officials have never seen him so anxious or exercised, before or since. Equally, they have no sense of a ‘guilty secret’ that might be rooted out in the inquiry. Some pressure on him eases after Hunt, who has himself been brought under intense scrutiny, provides what are generally considered reasonable explanations for his decisions on BSkyB. Cameron’s appearance in front of the inquiry adds to the febrile atmosphere inside Number 10 during the summer of 2012. The unravelling of the Budget, unpopularity of the NHS reforms and threat of a fuel strike all contribute – as we see in subsequent chapters – to falling poll ratings for Cameron personally and the Conservatives. Aside from the respite of the Olympics, this is a bleak time. Discussion inside Number 10 is about a general feeling of drift and loss of grip as much as it is about Leveson.

The 2,000-page Leveson Report arrives in Downing Street on 28 November 2012. Leveson had indeed moved, as expected, with commendable speed. As with the Saville Report, Number 10 is given twenty-four hours to prepare its response before publication. Llewellyn, Oliver, Dowden and Heywood pore over the principal findings. There is huge relief that the inquiry found no evidence of wrongdoing or impropriety by either Cameron or Hunt. It also finds there was no breach of the ministerial code. Had Hunt not been exonerated, his inevitable resignation would have been very damaging indeed to Cameron. There is, however, a serious sting in the tail. Cameron always recognised that the inquiry could be a minefield, and his apprehensions are justified in the recommendation that a new body to regulate the press be set up. Even though this body would be non-statutory, its existence would be ‘underpinned’ in legislation. The Guardian is positive, News International, understandably, are not overtly hostile. The Telegraph group is against, but the main opposition comes from the Mail group. The report divides the coalition. Clegg approves of proposals to protect the public from unjustified media intrusion. Cameron’s view on regulation is more nuanced. He doesn’t want to impose anything that smacks of political interference with a free press, fearing that any party that introduces mandatory regulation will be ‘done over’ all the way up to the next general election. The notion also grates with his instinct on the sanctity of press freedom.

With Labour and Lib Dems in favour of regulation, and the press overwhelmingly against, Cameron’s response is to hand the problem over to his ‘arch-fixer’, Oliver Letwin. Following negotiations with James Harding, outgoing editor of The Times, Letwin proposes on 14 March 2013 that press regulation be overseen by a Royal Charter, similar to the one that brought the Bank of England and the BBC into being. But the Royal Charter is not a compromise that the press will accept because it still maintains the spectre of press regulation, anathema to most of the profession. The Spectator leads the way in declaring it will not sign up to any Royal Charter. In April, the press produces its own proposals.24 Any collective will to act is being lost. The whole fandango to make the press more responsible and accountable fizzles out. Inevitably, many think.

There is a final twist in the tale. In October, a romantic affair between Rebekah Brooks and Coulson is revealed at the phone-hacking trial. It makes Cameron’s judgement in befriending both appear even more tawdry. On 24 June 2014, the verdict of the court is announced: Brooks and other defendants are cleared, Coulson is found guilty and jailed for eighteen months. ‘I think, once again, it throws up very serious questions about David Cameron’s judgement in bringing a criminal into the heart of Downing Street despite repeated warnings,’ is Miliband’s fiery response.25 To add further embarrassment, Cameron decides to go on television to make a ‘full and frank apology’ for hiring Coulson.26 His comments are immediately criticised by the judge presiding over the phone-hacking trial for launching ‘open season’ on Coulson while the jury is considering other charges against him. The jury is later discharged and a retrial is announced. ‘It was unwise. He should have taken some legal advice first, but I doubt whether it crossed David’s mind,’ Ken Clarke, a former QC, tells the media.27 On 21 November, Coulson is released from prison with a tag under curfew, after serving five months.28

Cameron was greatly unsettled and traumatised by the whole episode. Exceptional though Coulson was as his communications director before and after Cameron became PM, his appointment was a very major error of judgement given the toxicity of the phone-hacking scandal. It revealed how naive Cameron was in dealing with figures far more worldly-wise than him, above all the Murdoch family and Rebekah Brooks, and how flawed his openly trusting approach could be, as indeed could be that of his inner circle. They were a world apart from the harder-nosed courts of Blair, with figures like Campbell and Mandelson, and of Brown, schooled in Labour’s tribal politics.

By initially backing Leveson but then turning away from its recommendation for statutory regulation, Cameron further managed to earn contempt from all sides. The cynical Whitehall view is that ‘governments in the end always give way to the press, every single time’. The fact that Cameron’s worst episode as PM came in one of the areas where he had personal expertise, public relations – he had been director of corporate affairs at ITV company Carlton in the 1990s – makes it all the more perplexing. He displayed insufficient maturity in understanding the dignity of the office of prime minister and the need to be above suspicion, which includes ensuring that one’s close friends are also above suspicion. Most prime ministers have tumbles and lapses in Downing Street – the pressure is so intense, it’s not surprising. The question remained: had Cameron learnt sufficiently from his errors of judgement?