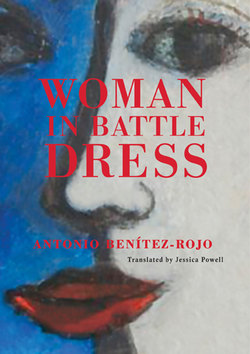

Читать книгу Woman in Battle Dress - Antonio Benítez-Rojo - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

THE URGENT NEED TO SEE Robert, to feel myself in his arms and to hear him say that he loved me; to fall asleep at his side in a big bed with white pillows and feel the heat of his body on my skin; to walk, arm in arm, along a tree-lined avenue, the leaves already crisp, glorious in their agony of gold, burgundy, and orange, and to swear my eternal love for him; to sit with him in some café in Ulm, or perhaps Munich or Augsburg, full of tobacco smoke and the sweet smell of fried onions and sausages smothered in mustard, to agree on the date and the place and the church and the time and all the other details of our wedding. (“The sooner the better,” counseled Maryse.) Yes, my desire to reunite with Robert grew within me like an endless stairway that seemed to lead to nowhere; the hours passing slowly and torturously as we doggedly followed the wagons laden with munitions and provisions through the streets of Württemberg, of Swabia, knowing that up ahead, somewhere far up ahead, marched the 5th Hussar Battalion, with Robert among them. There was no way to quiet my mind, nothing to distract me. Françoise, for some mysterious reason, was reading The Genius of Christianity, her lips moving as though gnawing on the words, her finger tracing the lines so as not to lose her place with the continual jolting of the carriage. If I decided to take advantage of a moment in which our carriages were stopped to visit Maryse and Claudette, I invariably found them going over song lyrics and dramatic dialogues, and I couldn’t help but feel like an intruder in their artistic endeavors. I didn’t doubt the affection Maryse felt for me, but she and Claudette were bound by links forged in Saint-Domingue, by a tumultuous and private past to which I did not have access, which they shared in the simple exchange of a glance, or a slight smile of understanding. And so it went all the way to the Danube, with me writing desperate letters to Robert whenever we stopped, copying the same paragraphs over and over again, watching the ink supply dwindle while still receiving no news, or at least any worth mentioning, beyond the laconic “all’s well” that circulated daily among the 5th Battalion, all the way from the Chief of Staff down to the last supply wagon. Just at the break of dawn one gray morning, we heard a distant thundering from the east. Half-asleep, I stuck my head through the carriage window and asked Pierre if a storm was coming. “It’s the war, mademoiselle!” he shouted from the coach-box. “We’ve arrived at the war!”

The following day we discovered that the battle had been fought in a place called Wertingen, on the south bank of the Danube. We passed a long line of Austrian prisoners, their white uniforms earth-stained and bloodied. They were being led by a contingent of Mounted Chasseurs who drove them forward, shouting at them as though they were oxen, and threatening the stragglers with their curved sabers. I jumped out of the carriage and planted myself in the middle of the road: The Hussars of the 9th Regiment? No, they had not participated in the battle. Robert Renaud? He is with General Treilhard. No, he’s with Field Marshal Lannes, as an aide-de-camp. No, I saw him yesterday in General Gazan’s convoy. Don’t worry, I’ll be sure he receives your letter. Consider it done, citoyenne, I’ll give him your message as soon as we return from Stuttgart. I’ll do what I can, citoyenne, I promise you. . . .

After that first victory, the nervous unease I’d been experiencing transformed into an ardent patriotism—a feeling that grew, from one day to the next, from a simple fluttering to a veritable fervor. I longed for more battles, more victories, and, above all, to see Robert marching triumphantly through the streets of a conquered city. While I’m sure my zeal had something to do with the enthusiasm of youth, I wasn’t the only one infected with what Maryse called “Napoleonic fever.” Françoise, who, a week earlier, had declared Europe to be drowning irrevocably in a bottomless pit of blood, and who dreamed of one day living serenely among the savages of America, stopped reading Chateaubriand and began praying with me for the triumph of France, of Napoleon and of all the heroic soldiers in our Grand Armée. Pierre, for his part, appeared to have forgotten his republican ideals and began to wear, night and day, a Cuirassier’s helmet that he’d found under a tree, greeting everyone he met along the road with an adamant: “Vive l’Empereur!” Even Maryse and Claudette, until that moment nonchalant, brimmed with joy at the printed proclamation, crumpled and smudged though it was by the time it reached us, that announced the Austrian debacle at Ulm. Mack’s army, in fewer than three weeks, had melted like butter: of one hundred thousand men, twenty-five thousand had died, forty thousand had fallen prisoner and multitudes of cannons and flags had been captured. The proclamation concluded with the revelation of Napoleon’s next objective: to take Vienna.

That evening, we uncorked two bottles from our wine stores. Then, under a boundless October moon, Maryse joined her guitar with the jubilant violin and traverse flute issuing from nearby carriages, and, in time to Claudette’s beats of the tambourine, she sang and danced well into the night.

After the victory at Ulm, we stopped fearing that an officer of the Intendance might requisition our horses. Mack’s surrender had re-provisioned the Grand Armée with hundreds of excellent mounts; so many, in fact, that some animals—though certainly not those that had belonged to the Austrians—were sold among the women and Jews following behind the troops. Other, more exhausted horses, were sacrificed in order to provide fresh meat to the regimental field kitchens. Pooling some of our money, Maryse and I bought an enormous horse with an indifferent expression and flayed hindquarters that had served with the Cuirassiers. He was thin and his ulcers reeked, but Pierre had insisted on the convenience of having a mount that would allow him to be in better contact with the farmers and merchants traveling behind us, and we deemed his judgment a reasonable one. We named him Jeudi, for the day of the week we’d acquired him, and we tied the lead on his halter to the rear of my carriage. By the third or fourth day, I worked up the courage to ride him. I put the bit on him myself and moved the reins from one side to the other so that he could become accustomed to my hand. Then, with the help of Pierre, who had also loaned me his boots and a pair of breeches, I leaped up into the saddle and took him out onto the road. Immediately, I knew we had not wasted our money. Jeudi had been well trained and obeyed, with little resistance, the pressure of the reins and spurs. Even if his walk was a bit ponderous and his trot too pronounced for my weight, it turned out that my legs were long enough to squeeze him tightly about the flanks. I was soon awash in the joy of riding and I remembered the afternoons in Foix when I’d gone riding with Aunt Margot—both of us mounted astraddle, as men do—along the edge of the forest until we met up with the road to Toulouse, where we would turn and race at a dead-level gallop all the way back to the château. (How grateful I am for the six years of riding lessons she paid for! The old cripple Laguerre, a former Captain who had lost an arm at Valmy and who lived, much beloved, in the village, used to tell me almost daily: “A horse, at the proper moment, can be worth more than a castle, mademoiselle. I will stop accepting payment from your Aunt when I see you gallop all the way to the forest ranger’s cabin without using your hands, jump over the hedge and ford the river with the water up to your neck.” That old centaur was the best teacher I could ever have asked for. When had Laguerre died? Why had I not asked after him when I returned to Foix? Oh, the things one leaves undone!) As I rode happily across the expansive plain, alongside the slow-moving train of carts and wagons, a feeling of independence swelled within me, a self-confidence that I’d never known before. For the first time ever, I felt in charge of my own life. I felt like a woman. As I dismounted, a resolution sank into my brain with the decisiveness of a nail: I would go to see Robert.

“You’re mad,” Maryse said, when I told her of my intention.

“Yes,” I replied, laughing. “Mad with love. I want to see my man, I want to hug him and kiss him and speak to him of our wedding and tell him that I love him more than anything else in the world. I must see him, Maryse.”

“Don’t be a fool, Henriette. I wouldn’t be able to go with you. Even if we were to buy another horse, I wouldn’t know how to ride it. I’m a city girl, my dear. However,” she added, suspecting that my decision was irrevocable, “there is Pierre. Pierre could go with you. Claudette or Françoise could drive your carriage and—”

“I appreciate your good intentions, but no. I feel I must go alone. After all, Robert is my business.”

“You don’t know what you’re saying. Do you imagine that you can just trot calmly by an entire army division without anything happening to you? You’d do well to think of yourself as a jar of honey and of Lannes’ troops as flies. Here, in the rearguard, things aren’t so bad. But there, out in front of the provisions wagons, where the bugles sound at dawn, you’ll be under the dominion of war. It’s not by accident that the regulations prohibit women from visiting the troops.”

“I’ve thought of all that. I’ll pin up my hair and put on Pierre’s Cuirassier’s helmet. I’m sure he still has his white doublet among his things, as well as his blue dress livery. Françoise is an excellent seamstress and I know she could work miracles with all of that. What’s more, I’ll travel across the plain, bordering the road. From a distance, they’ll take me for a Cuirassier.”

“A Cuirassier! And where, may I ask, are your mustache, your saber and your cuirass? Did you forget them in Strasbourg, or at the encampment at Boulogne? Don’t you see that, sooner or later, you’ll have to travel on the road and mix in with the soldiers? For the love of God, Henriette, you’re not a child anymore!”

Claudette and Françoise, who had been listening to us while roasting a rabbit under a solitary oak tree, came over to join in the conversation. Neither of them approved of my little adventure, particularly Françoise who, because of a few ill-fated affairs in Tarbes, where she was from, now kept her distance from men. But over the course of dinner, once they saw that I was not going to budge, they gave up trying to talk me out of it and fell silent.

“The fact is, you’ll never pass as a Cuirassier,” said Maryse, chewing pensively on a rabbit foot.

“I’m as tall as a man,” I protested.

“It’s not only height that makes a man, my sweet. Oh, how well I know that to be true! A man is many things,” said Maryse.

“You could be an aide-de-camp, they are usually quite young,” ventured Claudette timidly.

“No, no,” interrupted Maryse. “Even the most inexperienced soldier knows what the different uniforms look like. Henriette would be noticed immediately. Some will think she’s an Austrian spy; others, that she’s a prostitute. It would not end well for her. We must think of a different disguise. Something improbable. The more improbable the better, in fact: a priest’s frock, a Jew’s topcoat, a Bavarian vest. The mustache won’t be a problem. I have them in all colors and sizes in my costume trunk. I even have beards for a Turk or a king. In Boulogne, we had the opportunity to perform parts from various operas, among them, The Caliph of Bagdad and Richard the Lionheart, both highly praised, I might add. I even managed to convince your beloved Robert,” she added, flashing me a coquettish smile, “to perform an inspired rendition of a passage from Grétry’s Blue Beard.”

“With or without a beard, in a cassock or a topcoat, she won’t fool anyone,” asserted Françoise, shaking her head in disapproval. “What would your Aunt think of all this!”

“If Aunt Margot were here in my place, she wouldn’t hesitate for even a second. In fact, she’d probably be in Robert’s arms at this very moment,” I replied blithely.

“Well, that’s enough arguing,” said Maryse. “May it be as God wills it. We’ll just keep thinking.”

In the end, it was Claudette who came up with the solution.

“We do have a Caliph’s outfit,” she murmured. “Wide-legged red pants, a green vest and a turban. Henriette could pass as a Mameluke. Their uniforms are very irregular. We also have a curved dagger and a scimitar.”

“I’ve never once seen a Mameluke on these roads,” said Françoise. “And anyway, I’ve heard that they have dark skin.”

“Claudette is right,” said Maryse, her eyes flashing with excitement. “The Mamelukes serve under General Savary, in the Imperial Guard. It might be assumed that you were delivering an important message. The matter of skin color is nothing; I have makeup for every possible race of humanity. The only problem I can foresee is that Mamelukes, when they open their mouths, invariably mangle our beautiful language.”

“I know quite a bit of Spanish. I can imitate the Spanish accent,” I said, enjoying myself. “I am a Mameluke with General Savarrry,” I added, garbling the words and hollowing out my voice.

“That could work if you invert the genders of nouns and only use verbs in the infinitive. Merde, if Molière could only hear me!” concluded Maryse.

And there I was, trotting along the left-hand side of the road, my skin tinted a chestnut brown and dressed up as a Caliph, although I must have looked more like a Turkish clown, since every soldier I passed, without exception, pointed and burst out laughing at the sight of me: “Have a good day, Lieutenant Mohammed! Mecca is behind you, cretin! Ugh, it reeks of of camel! Has the carnival arrived?” they shouted. But the fact was, pressing ahead through the mockery and the laughter, I was getting closer and closer to Robert, and leaving the rest behind: the carts laden with barrels of flour, rice, peas and lentils, jugs of oil, strings of garlic, casks of wine and cognac and huge rocks of salt, as well as the contingent of walking meat—old cattle slavering at the mouth, lame and poorly patched-up horses. By midmorning I had already counted fifty wagons piled high with animal fodder, uniforms, saddles, harnesses and even drums. By noon, thanks to Jeudi’s long stride, I had come to the ambulances, and to the wounded, calm and as silent as blindfolded marionettes waiting for someone to pull on their strings (and if Robert were among them?). Then I passed the wagons filled with powder kegs and munitions, the cannons pulled along by four horses—the howitzers by six—and the lines of artillerymen on foot, whose gray uniforms I had already learned to recognize. Then I left behind the endless companies of musketeers, many of them barefoot and in rags, some clenching empty pipes between their teeth, others talking amongst themselves, but most of them quite serious, surely thinking of all they were missing—a bed, a meal of roasted meat, the kiss of a loved-one. And thus marched the 5th Battalion on the road to Linz, across the plains and cropped, straw-colored fields, through a sudden cool breeze that foretold of rain, a wind out of the west that sent shakos and balls of snarled hay tumbling.

“Where are you going, Mameluke?” demanded a Dragoon lieutenant who, flanked by half a dozen men, had blocked my way.

“9th Hussars!” I cried, pulling up on the reins and forcing poor Jeudi, who was already past the point of exhaustion, to rear up on his hind legs.

“They are over there,” said the lieutenant, looking at me curiously and extending his arm toward a distant cavalry troop whose colors were blurred in the whirls of dust and the strange violet light of that afternoon. “Your horse is on the verge of collapse,” he added, noting Jeudi’s ragged breathing and lathered muzzle. “But this is not a Mameluke’s horse.”

“Cuirassier horse. My horse break hoof,” I said firmly.

“From whom is your message?” he asked, with a suspicious air.

“General Savary. Imperial Guard.”

The lieutenant nodded assent. Before turning his horse, he advised me to dismount and to go by foot along the road. “You needn’t hurry. We’ll be stopping shortly, as soon as the sun sets . . . or the rain begins,” he added, peering at the thick clouds in the western sky.

Accepting his advice, I crossed my leg over the fleece that covered Jeudi’s saddle and jumped to the ground. After ten hours of riding, my muscles ached atrociously. I took a few steps and promptly realized that the pain in my waist and upper thighs would make it nearly impossible for me to walk. Suddenly, as though he’d only been waiting for me to climb off his back, the noble Jeudi folded his front legs, gave a muffled snort, and fell on his side, hooves in the air, smacking the ground with a dull and fatal thud. I knew immediately that there was nothing to be done. That old horse had fought his final battle. This time, he hadn’t charged against an enemy battalion, but rather, against time, my time, my desire to reach Robert as soon as possible. And he had lost. Unable to stand, he’d be slaughtered at dawn and served to the musketeers I’d seen marching a few hours back. Yes, I thought, horrified, Jeudi will be disemboweled, quartered, and eaten, just like so many other useless horses. I could not bear to think of it further. I merely untied the saddlebag containing my jewels and papers, and abandoned the rest of my luggage. With an abrupt gesture, I turned away from Jeudi, and began walking toward the road, by now scarcely visible. My legs were stiff, as though made of wood. On top of everything, it started to rain, first a few fat, scattered drops that pelted my ridiculous turban like hailstones, but quickly becoming a torrential downpour.

I have no idea how far I walked. In my memory, I see myself—as sometimes happens in dreams—wandering through the rain and the night like a lost little girl, crying out in anguish and desolation, my voice gone hoarse from screaming Robert’s name.

This morning, as I always do after drinking my ounce of rum cured with garlic cloves—a Cuban remedy, highly recommended for rheumatism and as a strengthening tonic for the body—I began to revise the pages I wrote yesterday and crossed out, in red ink, many unnecessary adjectives, a defect characteristic of my writing, as is my illegible handwriting—a doctor’s script that is difficult, even for Milly, to transcribe cleanly. I also discarded an episode that, no matter how hard I tried, I could not manage to narrate in a natural way, perhaps because, in it, I spoke of how I had finally reunited with Robert on that harrowing night. In any case, my conscience is clear; I have spared from posterity those “sublime and poignant lines”—as my Milly, ever the romantic, called them—in which I described our reunion, how safe I felt under his cloak, the tender words and professions of love that we whispered in each other’s ears beneath the drumming of the rain, how, from then on, Robert called me, affectionately, “my little Turk.” To complete my narrative of the episode, I’ll mention that, days later, I entered Vienna hidden in a wagon belonging to Ma Valoin, sutler of the 9th Hussar battalion, a voluminous and good-natured woman, without whose complicity I would never have been able to remain by my lover’s side.

Vienna surrendered on the 11th of November. The Grande Armée’s triumphal march lasted two full days and nights, though I, myself, was witness only to the cavalry passing by. Although the Austrian Court had fled to Budapest, the vast majority of Viennese citizens did not appear to fear our troops, so much so, in fact, that thousands of them lined up, on both sides of the road, to watch, openmouthed and somewhat shamelessly, as the incomparable military machine that had conquered them paraded by. Upon seeing the Mamelukes pass by, I asked myself how on earth anyone had mistaken me for one of those exotic-faced Moors with jet-black eyes. It also amazed me, dressed now in Ma Valoin’s drapey clothing, with a red handkerchief knotted about my head, that people were unable to see through my latest disguise. (“The habit makes the nun, my dear,” Maryse would say, years later. “If you dress in mourning, you’ll be a widow or an orphan; if you dress as an old woman, you’ll look ten years older than you are; if you don an ermine cloak and a golden crown, you’ll be a queen.”) In any event, after spending an entire morning watching thousands of Grenadiers, Dragoons, Chasseurs, Cuirassiers, Carabineers, Gendarmes, Lancers, and Hussars file past, I had the thrill of seeing Robert parade by in his dress uniform, his saber unsheathed, his white glove holding the reins of his mount Patriote as delicately as if he were carrying a cup of tea. We were married that same week.

My honeymoon lasted for three nights—during the day Robert worked inspecting the city’s arsenal, whose stores of weapons and gunpowder had been captured intact. I could narrate those nights one by one, during which Robert went about successively filling all the portals of my body with love, erasing the rushed and mediocre experience in Strasbourg. How shall I explain those long hours dedicated to my apprenticeship in the erotic arts? Though “apprenticeship” isn’t the right word, since what I mean has to do with that false passivity of the novice who, though appearing to give herself over like a living statue, does so with all of her senses in a heightened state of alert; sight, touch, smell, sound, taste, all of them presaging pleasure, anticipating it by means of a damp and secret memory, an ancient memory that goes beyond instinct and that springs fluidly forth from the great goddesses, the immortal women, Hera, Leto, Demeter, Aphrodite. How can I describe those hours during which my body signed the sexual contract once and for all, the contract of all contracts, origin of all origins, the indelible writing of the fingers and the nipples, of the tongue and the clitoris, of the unyielding junctions and the intimate liquors? What words could I use to recreate, with my pen, the fatigue that comes from continual pleasure, that fainting from desire at the end of the night, when starlight and candlelight burn out to make way for a clear dawn of sweat-soaked sheets, tousled hair, and swollen eyelids, when sleep, sudden and heavy, drapes over the temples like an iron crown, vanquishing the body, exhausted, fingernail-raked, bitten, sucked, bruised; a body that soon wakes, yawning and stretching sleep-numbed arms to bolster itself with a breakfast of wine and cold meats and pleasantries until a deliberate kiss ignites desire all over again?

“I can’t anymore, Robert. I can’t,” I’d told him. “If I don’t get up this very minute, I’ll die between these sheets. I need to come up for air. And anyway, I must see to the matter of my dowry.”

And a short time later, bathed, my hair done up, bejeweled and attired like a Viennese lady—I’d spent the last of my money on two new dresses, a cape and a hat—I watched as Robert braided his hair down the sides of his face and waxed his mustache in front of the mirror, an operation he carried out with great seriousness in spite of my teasing. Satisfied with our appearances, we said goodbye to Frau Wittek, the widow who’d provided us with a room on the second story of her house on Bäkerstrasse, and stepped out into a lustrous morning in which the sun set the colors of the fallen leaves ablaze with light and shone cleanly on the monumental façades of Vienna—St. Stephen’s Cathedral, the Hofburg Palace. . . . Oh, my beloved Robert, how proud I felt on your arm as we wandered the streets in search of the banker that the kind priest at St. Michael’s had recommended to us. How surprised I’d been by your command of German: Guten Morgen, gnädige Frau. Wir suchen Herrn Kesslers Bureau. Once we’d found the house, we crossed the vestibule and entered a busy office in which several men with black bankers’ sleeves affixed to their shirts were pouring over account ledgers and piles of papers. “Herr Kessler?” Robert inquired, and an elderly man, hunched and very pale, with hairy, agile hands, stopped moving the balls on an abacus and stood up.

Herr Kessler spent half an hour carefully examining our papers, scrutinizing mine in particular. Finally, he cleared he throat and addressed Robert in a guttural and disjointed French: “Everything appears to be in order, isn’t that so? Were it not for the war. . . . Ah, the war. . . . I would be able to advance you a larger amount. Surely you understand. . . . The collection fees, no? Excessive, Monsieur Renaud, excessive. Just imagine, a bill of exchange to be cashed in Toulouse. We are in Vienna. . . . Such an ill-fated war, don’t you think? Well, we shall be able to do something for you. Not much, to be sure, in these times. . . . There is hardly any money left at our disposal. And gold, well, gold is scarce, monsieur. The Emperor has taken it with him to Hungary. Of course, I realize . . . you are a newlywed. . . . The madame has a dowry. . . . Quite a large amount, I should be able to advance something to you . . . ” And on and on he went, talking without pause as he consulted a mysterious ledger that he had taken from his desk drawer, and knocked the balls on the abacus together, moving them from here to there with vertiginous speed.

“And?” said Robert impatiently.

“I can give you, tomorrow, at the same time . . . four hundred Guldens.”

“We need five hundred,” bartered Robert.

In the end, the amount was fixed at four hundred twenty-five Guldens. Since Robert was to rejoin his regiment the following day, early, as always—Lannes had not stopped over in Vienna and was already on the march in the direction of Olmütz—Herr Kessler agreed to bring the money to me at the flat on Bäkerstrasse, initiating a business relationship between us that would be revived some months later.

With nothing better to do until six that evening when the opera would begin, we headed toward the Prater, an enormous park on the outskirts of the city that we’d been told was nothing short of miraculous. (You, reading me now, if you can travel through time—and I say this with more hope than irony—do not fail to visit the Prater of my youth. There you will find gorgeous paths lined with chestnut trees, shops, cafés, taverns, restaurants where you’ll eat fried chicken and drink Pilsner beer and Hoffner wine. Seated at a table facing the Danube, you’ll admire the tall willow trees that line its banks and the groups of deer, gentle as sheep, that graze upon the grass. If you like horses, as I do, you could ride on an excellent course without fear of crashing into anyone, or step up to an arena at which you’ll be dazzled by daring equestrian exercises. Or, you might simply pass the time watching the children wave to their parents as they spin about on a carousel, mounted on brightly-colored plaster steeds. If you’re a lover of music and dance, follow the main avenue until you come to the Augarten, where you’ll find dance and concert halls and where the air is filled with waltzes and marches and songs and the sweet murmurings of lovers.) After a lunch of sausages and beer, we returned to the city.

Despite the normalcy with which the Viennese had carried on with their daily lives, at sunset they began to return to their houses. Few people remained in the streets, and, upon arriving at the theater, we saw that the foyer was nearly empty. There were scarcely any women, and the men, for the most part, were officials with the Grand Armée. Given the low attendance, we had no trouble securing a pair of box seats. As the orchestra was tuning their instruments, a hushed murmur ran through the theater; a dignitary with gray hair and a deliberate mien had just occupied the Imperial box. “It’s Talleyrand, the Grand Chamberlain of the Empire,” whispered Robert, rising from his seat to stand behind me, his bearskin hat resting, in a soldierly manner, between his forearm and right shoulder. At a sudden burst of applause, I turned my gaze to the orchestra pit. In walked the conductor, a small, bespectacled, dark-haired man who acknowledged the applause with a brusque nod of his head, then sat down perfunctorily on the bench in front of the pianoforte. I looked at the program. He was the composer of Fidelio, the opera being premiered that evening. The music was quite good but what really fascinated me—possibly because Robert had sunk his fingers into my hair and was caressing the nape of my neck—was to see how the resolute Leonore, having donned men’s clothing in order to rescue her husband, went about seducing the jailor’s daughter, arousing in her an ardent passion that resonated within me. Motioning to Robert to bend his head near mine, I whispered in his ear: “You see, I’m not the only one who dresses as a man to get what she wants.” Robert smiled and said nothing. That night, the last we’d spend together on Bäkerstrasse, we made love until dawn. When we said our goodbyes and I begged him to be careful, he began a sentence, but left it unfinished, as if he had decided that saying it would have hurt me too much: “Any hussar who hasn’t died . . . ” Then he kissed me once more and, looking me in the eyes, murmured: “I’ll be careful, my little Turk.”

All my efforts to locate Maryse and Françoise in Vienna had failed. And not only that; I had reason to believe that I might not see them again for a long time. It was rumored that days ago, near Linz, a pack of marauders had attacked the women and merchants following the army. True or not, the fact was that all camp followers had been detained in Linz, making it impossible for them to continue on to Vienna. The detention order had come down from the General Staff, and had been published in the Wiener Zeitung, now directed by an Austrian in the service of the French. Robert himself had translated the curt text for me on the morning of our wedding. As it was rumored in the cafés, the order was an attempt to mitigate the burden on the Viennese, who would already be overwhelmed with the necessity of feeding and housing the twenty thousand men that Napoleon would leave behind to secure the city. “Don’t worry,” Robert had said, seeing my anxiety rise. “You know Maryse. She’ll find a way to get to Vienna and find out where I’m stationed. If she arrives after I’ve finished my assignment, I’ll leave her a note in the arsenal.” But a week had gone by and there was still no word from her.

Fortunately, the same was not true of my uncle, who appeared at Frau Wittek’s door two days after Robert left. Always thinking ahead, Doctor Larrey had determined that, while the bulk of the medical service would follow the Imperial Guard on their march to Moravia, Uncle Charles would remain in Vienna to organize large-scale convalescent hospitals. When I told him of my adventures as a Mameluke and of how I’d found Robert in the middle of that stormy night, Uncle Charles rose from the armchair and took me in his arms as affectionately as if I were his own daughter. “You have no idea how happy it makes me that things have gone well for you. Your aunt must be helping you from heaven. I owe you a wedding gift. You know, army life is not easy for any woman, but it’s especially difficult for unmarried women. Anyway, have you heard from Maryse?” he asked in an off-handed manner, returning to his chair.

“I’m sure she’s in Linz. Françoise too. If I could get my hands on a safe-conduct pass that would allow me to come and go freely, I’d rent a carriage and go in search of them,” I said, hoping that he would help me attain such a permit.

Frau Wittek appeared in the doorway and gestured for us to come to the table. Refusing to sit with us, probably for patriotic reasons, she served us the wine that Robert had bought, white bread and the best of what she had left in her cupboard. She was a good woman who, torn between loyalty to her country and her habit of treating her guests with generosity, couldn’t make up her mind how to behave with me, the wife of an invader.

After helping himself to a thick slice of ham, my uncle raised his glass and said: “A toast to those not with us tonight.”

“Yes,” I said, raising my glass as well, “and may their absence be brief.” Swallowing my first mouthful, I added: “You have no idea how much I miss Maryse.”

“Maryse, yes, of course. I miss her too. We are good friends. It’s just that now is not the best moment to travel to Linz,” said my uncle, and, turning to address Frau Wittek, who was setting a delicious-looking apple tart on the table, he said, still smiling: “Your mother was a whore and your food smells like shit.”

Frau Wittek, whose knowledge of French was limited to two words—the bon jour with which I greeted her each morning—smiled back, and served him an enormous helping of apple tart.

“Well, one can never be too sure. There are many spies,” Uncle Charles said, by means of apology. “The fact is, somewhere in Moravia we will fight a great battle against Kutuzov’s Russian troops, who are coming down from the East with Czar Alexander, and against what remains of the Austrian Army. Only Napoleon knows exactly where it will take place. Larrey told me this before leaving. It will be a decisive battle. Just imagine it; a battle of three emperors.”

And, as it happened, this was precisely what Austerlitz would come to be called: the battle of the three emperors. At first it was nothing more than a rumor, dismissed by most of the Viennese; then, as the details of the great French victory came out in the newspapers, many said it was pure Bonapartist propaganda; days later, when the prisoners and the wounded began to arrive in the city by the thousands, there were some who still insisted that those ragged men were Russian deserters, forced to take part in some great ruse. But—as Aunt Margot always said when faced with an undeniable truth—one cannot cover the sun with a finger, especially not the sun of Austerlitz, the sun that illuminated, as no other, Napoleon’s military career.