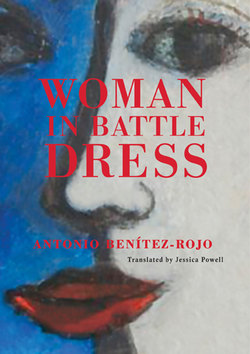

Читать книгу Woman in Battle Dress - Antonio Benítez-Rojo - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

AT THE BEGINNING OF SPRING, after an uncomfortable journey across Prussia and Saxony, I stopped in Munich to put my affairs in order. I stayed in a guesthouse on the banks of the Isar and hired an agent to take charge of the sale of the house where Robert and I had lived. I insisted that I didn’t care if I lost money in the sale; I needed to leave as soon as possible. I spent the eighteen days that I ended up staying in the city wandering through its streets and plazas, pointedly taking my time so as to fix in my memory the red bricks of the cathedral, its unfinished towers, the black statue of the great Ludwig, and, waving from the pillar of the nave, the Turkish flag captured in Belgrade; the baroque façade of the Theatinerkirche, where I liked to go from time to time to look at the Venetian paintings; the old doors on Neuhauser Strasse, the Marienplatz, with its column honoring the Virgin Mary, patron saint of the kingdom, and, facing the plaza, the squat building of the café, our café, the Hussars’ table, Robert reading the Moniteur. . . . It was a means of saying goodbye.

I was planning to meet up with Maryse in Stuttgart. I would spend a few days with her, then travel to Paris to visit Uncle Charles, who’d recently been put in charge of improving medical instruction in the city, and from there, continue on to Toulouse, where I would stay until my tenant’s rental contract was up and I could move into the château. Foix had suddenly become not only the tiny kingdom of my childhood and adolescence, full of tranquil days and pleasant horseback rides, but also something like a place of retreat, a silent monastery surrounded by forests where I could mend my heart in solitude. Robert’s death had left me empty of emotion. I ate and drank without appetite and my sleep was broken and exhausting. More often than not, I awoke with a headache and the taste of ashes in my mouth. Although I wasn’t terribly hopeful, I had the idea of asking Maryse to come with me, together with her Théâtre Nomade—I’d learned from her letters that this was the name of her traveling show that, in little more than two years, had become a retinue of carriages, wagons, wheeled cages, and mules that transported more than forty people, “and that’s without counting, dear Henriette, the many animaux savants, dancing bears and dogs, a mathematical horse and a pair of ubiquitous doves that appear and disappear at the sound of the words hocus pocus. . . .”

I scarcely remember the journey to Stuttgart. I know only that when we saw one another, Maryse and I fell into each other’s arms in a commotion of hugs and tears. Oh, how we wept! We cried all together, Maryse, Claudette, Françoise, and I. We cried at the guardhouse, in the street, at a table at the guesthouse, and finally, in my room. Our eyes swollen and our noses red, we listened as each of us told what we had to tell, which turned out to be a great many things. The most surprising news was the romantic relationship that had developed between Claudette and Françoise. “It happened without us even realizing it,” said Françoise, matter-of-factly.

“In Linz,” added Claudette timidly.

Perplexed, I turned to Maryse for an explanation, but she merely smiled and shrugged her shoulders.

“And Pierre?” I asked, to hide my displeasure.

“He’s in charge of transportation for the troupe,” replied Maryse. “A very complicated undertaking. It’s not just a matter of leading our entourage, that’s nothing for him. It’s that there’s always one problem or another, a wheel to be replaced, too much cargo, a fire in the gypsies’ wagon, a lame mule, a leaky carriage roof, anyway, why bore you with the details, my sweet? He’s always busy. At this very moment he’s combing the streets in search of Tom, one of Frau Müller’s dancing dogs. I do hope he finds him; he’s the lead dog, and the show starts in three hours.”

That first night, overcoming my exhaustion from the journey, I allowed Maryse to take me to the theater, a humble and poorly lighted space. In any event, at the six-thirty curtain, not a single seat was vacant, despite the fact that this was their third performance in Stuttgart. Maryse’s appearance onstage was greeted with hearty applause. She wore a Venetian mask that resembled a cat’s face, and she was enveloped in a provocative white silk wrap that accentuated the sinuous movements of her body. I had never seen Maryse on stage before. I was amazed at her grace, her naturalness, the feline cadence of her undulating shoulders as she presented the evening’s program. Suddenly, there was a great boom and she disappeared in a scarlet cloud of smoke, replaced by the four Pinelli Brothers, acrobats whose skills were far superior to those I’d seen in Toulouse with Aunt Margot. They were followed immediately by the discordant strains of an off-key French horn, announcing “The Pursuit of the Unicorn,” a charade in which Pierrot, Harlequin, Pantalone, and Punchinello, mounted on broomsticks topped with horse’s heads, ran higgledy-piggledy about the stage, chasing a strapping, horned Columbine who is, at last, and as expected, mounted by Harlequin amid much kicking and bucking and waggling of hindquarters. Then came the gypsies with their bears, Pythagoras the horse, a group of fearless tightrope walkers, and Frau Müller’s dogs that, dressed as little ladies and gentlemen, danced a minuet and exited the stage, leaping through a ring of fire. The end of the first act belonged to Doctor Faustus Nefastus, whose black brocade cape sparkled with comets, stars, and moons embroidered in silver thread. His tricks were unparalleled, and I imagined that he must be one of the better-paid members of the troupe. For his final act—which I can’t resist describing—he locked Harlequin in a square box so that only his head stuck out, then covered his head with a red silk handkerchief that he pulled from between his fingers. Accompanied by a sudden drum roll, he sawed off the head, lifted the kerchiefed bundle from the box, and walked across the stage, gravely showing it to the audience. A clarinet sounded the tremolos of a Turkish tune and Claudette, dressed as Salomé, unfolded herself from inside the box, rhythmically beating a tambourine upon which the magician placed the red bundle—the presumed head of John the Baptist on the infamous platter. Then the pealing of the clarinet became frenetic and Claudette, changing the voluptuous modulations of her dance, began to describe quick circles across the stage, holding the tambourine aloft, first in her hands, and then atop her head. She came to a stop at last and the magician, covering her with his cape, intoned a spell that I would come to memorize from hearing it so often: Hocus pocus tontus talontus vade celerite jubeo. A tremendous thundering reverberated throughout the theater and, as the smoke cleared, a fully intact Harlequin appeared, straightening, in pantomime, his wayward head. Ignoring the hailstorm of applause, Faustus Nefastus—his real name was Piet Vaalser—repeated the same spell, and the four sides of the box fell to the floor, revealing a smiling Claudette, the silk handkerchief in one hand and the tambourine in the other.

After intermission, Pierrot, Harlequin, and Columbine, dressed in tight-fitting leotards, performed exquisite tragicomical pantomimes to the strains of a solitary and sublime violin. This was followed by two impassioned Shakespearian soliloquies translated into German, and two lively Mozart quartets, featuring Maryse herself. The evening ended with a circular, Roman-style march, in which horses, wagons, consuls, magistrates, and soldiers paraded repeatedly in front of an allegorically painted backdrop, inciting such a monumental reaction from the audience that the deafening beat of the drums was accompanied, to the very last, by applause and the incessant cries of “Bravo! Bravo!”

Captivated by the success of the Théâtre Nomade and its members’ lighthearted and carefree way of life, I felt my own life turning, day-by-day, away from nostalgia and toward unpredictability. My appetite returned, my sleep improved, and I realized that my vitality was returning. Halfway to Karlsruhe I decided to cancel my trip to Toulouse and I asked Maryse if I could stay with the troupe until my tenant’s lease was up in Foix.

“But dear heart, this business is as much yours as it is mine. Didn’t we start it together in Strasbourg with our two carriages?”

“Oh, no, Maryse! I couldn’t!” I said, moved by her generosity, and I slid over to sit by her side and hug her.

“Don’t be misled; we only manage to cover costs. The theaters keep the lion’s share of the money from our ticket sales. But when it comes to business, I’ve always tried to be a serious person,” she said, pulling away from me and giving me an affectionate shove toward the carriage window. “Come on, let’s talk seriously. To start with, I’ll tell you that it’s only by dint of a miracle that our little variety show even survives. Perhaps you, coming in from outside, can explain our success better that I can. I would not be lying were I to tell you that, for the most part, the show has created itself, as though it’s had a life of its own, independent of my desires and precautions. And it’s been that way from the very beginning. Musicians, actors, singers, gypsies, acrobats, well, everyone you’ve met, has joined up with the troupe purely by chance, without my having lifted a finger. Here’s how it happened: two years ago, when our carriages were detained indefinitely in Linz, I happened to see a concert hall still displaying a week-old program. I knocked on the door, intending to ask to rent it for a few nights, but the owners, like many Austrians, had fled to Hungary before our troops occupied the city. The caretaker who opened the door was terrified and allowed me to enter without argument. The place was small, as was fitting for Linz, but struck me as absolutely marvelous. There was a German pianoforte, a harp, and cabinets filled with printed scores and unused sheet music. Ignoring the presence of the caretaker, we installed ourselves in the theater. As we knew that the city’s newspaper was already dedicated to military use, we spent two days writing out the details of one of the programs we’d performed in Boulogne. While Claudette and I rehearsed, I sent Pierre and Françoise to pass out the announcements in the cafés. What can I tell you? The theater was filled to capacity, and not just that night, but all the others as well. The pianoforte was well tuned and my voice as clear as ever, although the one who stole our soldiers’ hearts was Claudette, who performed the Salomé and sang and danced merengues and calendas from Saint-Domingue.”

“She stole Françoise’s heart as well,” I said archly.

“It’s true. Although it surprises me less than it does you. I don’t know anything about Françoise’s past, but Claudette has more than enough reasons to distrust men. In any case, the Theâtre Nomade was born there in Linz. Surely you’ll remember the huge number of women who’d been traveling with the 5th Battalion. It’s true that there were all types among them, but some of them, like Claudette and me, were theater people. And not just theater people, but theater people whose resources had all but vanished, and who needed to earn a living. A young Jewish boy who was marching to Strasbourg with his father also joined us. Guess who he is? None other than Maurice Larose, our clarinetist, the jewel of our little orchestra. Of course the day arrived when we were finally allowed to move on toward Vienna. But I’m superstitious, my dear. I don’t know if I’ve told you that before. I prefer not to travel east if I can get away with traveling in any other direction. If you think about it, for us French, everything bad has always come at us from the east. It’s something my father used to say. And so, after buying a wagon and a new carriage, we set off for Salzburg, where we found the Pinelli Brothers and the Venetian Mimes. And there, I had to make a decision. My show had always been limited, more or less, to what now makes up the second act. And we’d gotten along reasonably well like that. But Rocco, the eldest of the Pinelli Brothers, convinced me that I’d do much better if I joined forces with his people and made room in the show for some circus acts, danseuses de corde, magicians, contortionists, animaux savants. ‘This way we’ll have something for everyone,’ he told me. And he was right. Later, in Mannheim, Frau Müller joined us with her dogs, as well as the gypsies and their bears, and in the market in Frankfurt, I found Professor Kosti with Pythagoras and also Piet, who’d just returned from touring in London, with Joseph Grimaldi, no less, and who, like me, was traveling across the Rhineland. And so it’s been. With the exception of giants, midgets, bearded women, hermaphrodites and other phénomènes that serve no purpose other than showcasing their physical oddities, I’m willing to accept anyone and anything in the realm of circus arts. And I’ll tell you another thing: if we continue to attract such experienced performers, I don’t see any reason that we couldn’t work in France, although not just yet; the public’s expectations are much higher there. But one day we shall cross that border. I’ve thought it all out: Strasbourg, Metz, Nancy. Little by little, we’ll be moving toward Paris. My city. Ten years, Henriette. It’s been ten years since I left Paris.”

“You’ll be back soon enough now. But what you’ve told me is simply amazing,” I said, in awe at the apparent ease with which she had organized such a complicated show. “Although I believe it’s more than just coincidence at work. I’d say it was your destiny. Of course you’ll return to Paris. You were born under a lucky star. That’s the main thing. I’ve heard that Napoleon, before promoting anyone to the rank of general, asks first if he was born under a lucky star. My star, on the other hand, well you know . . . Aunt Margot, then Robert.”

“Oh, Henriette, how little you know about my life,” she sighed.

But I did know at least a little. And I don’t mean her unfortunate relationship with Varga and the matter of the duel, things I never let on that I knew about. But one night in Vienna, in that moment of intimacy one slips into after making love, I asked Robert what he knew about Maryse’s life in Saint-Domingue. Whether because he always shied away from talking about other people, or because he actually knew little about Maryse’s past, he told me only that she and Claudette, after suffering many hardships, had left Saint-Domingue just before General Rochambeau’s surrender. “But let’s speak of happy things,” he’d said. “The stories about Saint-Domingue are too frightening. What do you think about throwing a banquet in honor of Constant’s birthday?”

“Forgive me,” I said to Maryse, ashamed. “I spoke without thinking. I know from Robert that you were very unlucky in Saint-Domingue.”

“Unlucky? I’ve suffered a great deal. First I lost my daughter’s father,” she said in a low voice. “Then I lost my daughter,” she added, turning her face toward the carriage window.

“Oh, Maryse!”

“It’s all right, Henriette, it’s all right,” she said after a moment, trying to smile beneath her tears. “But promise me something. Promise me that you will never speak to me of these things. I don’t know what came over me. I shouldn’t have told you.”

But those painful memories had already surfaced, and, like blind birds, they flew about between us, unable to return to hiding or to take flight. I drew her close. I hugged her until she understood that it would be better to give in to it and tell me everything. And so, beginning that very day, she surrendered up her story to me little by little, like the chapters in a feuilleton.

Shortly before the turbulent days of the storming of the Bastille—an appropriate date from which to begin many stories of my time—Maryse was a young and talented singer, increasingly well-received on the stages of Paris. She was in love with a married man, a wealthy mulatto from Saint-Domingue by the name of Jean-Charles Portelance, who had traveled to Paris to lobby in support of the rights of citizenship for people of color in the colonies, a category to which he himself also belonged. To this end, he was active in the Société des Amis des Noirs, an organization prominent in those years, whose members included notable men such as Mirabeau, Necker, Sieyés, and La Fayette. One day, Maryse discovered that she was pregnant. It was something that neither she nor Portelance had wanted, but they both adjusted to their new reality, if not with enthusiasm, then with calm resignation. And so, their daughter, who they named Justine, was born. After the first few months, and after a great deal of consideration, Maryse decided to live alone with her daughter and the wet nurse, since she believed it would be morally unhealthy for the girl to be raised in an illegitimate household. At first, Portelance did not approve of this separation, but, little by little, he grew accustomed to the arrangement and, like Maryse, came to believe that it was for the best, given their situation.

Despite the sincere love that bound the couple, their relationship was far from happy. This was not because Portelance’s marital status presented an emotional obstacle—his marriage was the result of an arrangement between families, and Madame Portelance, having already performed her marital duty in giving birth to a son, lived an independent life in Boston—but rather because their professional interests did not coincide and they scarcely found time to see one another. In addition to being an ardent idealist, Portelance was an intense and dedicated man who only had eyes for his political projects; when he wasn’t in his office writing an editorial for the Mercure, he was editing a pamphlet against the Club Massiac; when he wasn’t attending an Amis des Noirs meeting, he was at a secret meeting with an English abolitionist. Maryse was no different. Her career was on the ascent and, even during the lulls when she wasn’t part of the cast of a given opera, her days were full of other activities, from watching Justine play in the Jardin de Luxembourg, to taking voice lessons, from performing in a play or a concert, to visiting her dressmaker’s atelier for a fitting. Moreover, knowing that she was greatly admired, she enjoyed attending the theater and making appearances in musicians’ and artists’ salons, activities that held no allure for Portelance.

As time went on, and the revolution took an anti-Christian turn, their political opinions began to divide them as well. Maryse thought it an act of barbarism that the Notre Dame Cathedral should be co-opted in the name of Reason: “For the love of God, Portelance! Where will this end? Now we’re supposed to worship at the feet of the great Goddess Reason? What a disgrace!” she would lament. But more than anything, she was growing to detest the guillotine, and not only because the number of victims was constantly increasing, but also because she was convinced that the spectacle of public executions was irreparably corrupting people’s emotions.

“We’re becoming animals. How can you support this bloodbath?” She would demand.

To which Portelance would reply: “The road to hell is paved with good intentions. We’re at war and in the midst of a revolution, my love. Think of the guillotine as a necessary evil. It’s true that they’re taking extreme measures, but they’re also creating justice. Scarcely two years ago, despite my wealth and my education, I had no rights whatsoever. And today I do.”

And as their arguments went on with neither of them budging an inch, Maryse would feign a headache and leave Portelance’s house in a sour mood. Other times it was he who, taking his hat and cane, would brush Maryse’s lips with his own and take his leave, suddenly remembering that he had a dinner that evening with an influential member of the Convention. And it’s not that Portelance wasn’t repulsed by the continual rolling of heads, it was just that, a politician to the end, he believed that if the Convention were to abolish slavery once and for all—which had become his most cherished dream—it would do so impelled by its most radical faction. When the day finally arrived for that longed-for decree to be made public, Maryse, brimming with joy and immediate plans, ran to Portelance’s house to celebrate the occasion.

“You must be so pleased, my love. No one knows better than I how much time and effort you’ve dedicated to the toppling of that horrible institution. A toast to your success,” she said, raising the glass Portelance had just filled.

“A toast to the fraternity of races,” he said, raising his own glass. “It doesn’t seem possible. Can you imagine it? No more slaves. The French plantations will be worked by free people. The black man will be master of his own body again. Oh, if only ships could sail as swiftly as lightning! While we’re here celebrating the triumph of social justice, weeks will go by before those poor souls in the colonies will receive the good news.”

“Don’t spoil this happy moment with your impatience, my dear. The news will arrive in due course. Tonight we should think of us,” she said, setting her glass aside to caress Portelance’s hand. “After all, our moment of happiness has also arrived. You’ve finished your work and your affairs are in good order: your son is in school in Boston, your brother is in Philadelphia, managing your ever-increasing fortune, your wife leaves you alone, and I love you madly. The time has come for you to enjoy what you have, Portelance! In fact, just a few minutes ago, I was thinking that it wouldn’t be such a bad idea to leave Paris for a while.”

“Leave Paris? Good heavens, I’d have wagered that you wouldn’t leave Paris for all the gold in the world!” exclaimed Portelance. “And your career? Your friends?”

“Things have changed, my love,” said Maryse, deciding to reveal her most recent preoccupations. “Perhaps you aren’t aware that theater folks are falling out of favor with the Convention, or at least with Robespierre. Not even Talma the Great is exempt from suspicion. It’s rumored that he’s going to be denounced as a conspirator. It’s not exactly that I’m afraid, but you know well the opinion I hold of the Jacobins and you also know how I am. Sometimes I express my ideas a touch liberally and . . . who knows what could happen? But above all, I’m thinking of Justine.”

“Come now, Maryse. If you were under suspicion, someone would have let me know. I can assure you that you’re not in any danger, my love,” said Portelance in a soothing tone. “And yet, it’s true what you say: my work here is done. There can be no doubt about that.”

“Do you mean that you wouldn’t object to leaving Paris?”

“No, I would not object. In fact, I’d planned to tell you this evening that, eventually, I’d be going on a trip. I had been putting off telling you because I’d never imagined that you’d be of a mind to accompany me. Paris has always been your home.”

“Oh, my love, how happy you make me!” said Maryse, standing suddenly and moving to Portelance’s lap. “Do you know where I’d like to go? To Spain. According to Monsieur de Olavide, it’s quite easy to cross the border. There are theaters there . . . Madrid, Barcelona, Seville. How happy we’ll be! We’ll live apart from politics, isn’t that so? Promise me? And we’ll live together, like a family. Now that Justine has been asking me questions about her father, I see that my decision to keep her from you was a mistake. She’ll come to understand. . . . Tomorrow I’ll introduce you to Don Pablo de Olavide, a celebrated political exile. He’ll tell you all about Spain.”

“But, my dear, what would I do in Spain?” he said, smiling. “It wasn’t Spain I was thinking of.”

“Where, then?” asked Maryse, intrigued.

“To Saint-Domingue, of course.”

“But you yourself have told me that there are violent uprisings going on there, that the colony has been invaded by foreign troops,” protested Maryse.

“Precisely. They have named Chambon to implement the abolition of slavery decree. Any anarchy will disappear once they have the news. The black insurgents will unite with the French. The English will have no choice but to evacuate their forces. As for the Spanish, they’ll be relegated to their part of the island.”

Maryse disentangled herself from Portelance’s embrace, stood up, and, looking at him disconsolately, said: “And you’ll be going with Chambon, is that it?”

“Not exactly. I’m waiting to receive a large sum of money from my brother. We shall depart in a few weeks.” Portelance removed a habano from a case on the table, held a straw to the candle flame, used it to light the cigar, and watched the smoke rise. Finally, he said: “I won’t hide anything from you. I’ve been charged with a secret mission. I am to observe what happens in the country until the Convention sends a group of officials with legal powers.”

“I see. Back to blood and politics,” lamented Maryse. “As if nothing else existed in the world. Oh, Portelance, I’d had such hope!”

“I’m sorry to upset you, my love,” he said, trying in vain to draw her near. Without getting up, he watched her fix her hair and take her overcoat from the coat rack. “Don’t be silly, stay a bit longer. We should talk.”

“I’m all in a muddle, Portelance. I need to think,” said Maryse before closing the door.

That very night, on her way home, Maryse decided to break with her lover. She would go to Spain with Justine. It was a sudden decision, made from one moment to the next, without deliberation. When the carriage stopped at her street she told the driver to take her to Talma’s house. She knew she’d find Olavide there, fond as he was of rubbing elbows with musicians and theater types. She would ask him to write letters of introduction on her behalf to his friends in Madrid and Seville. But when she arrived at Talma’s house, Maryse saw two guards at front of the door. Fearing the worst, she instructed the driver to take her to Gervaise Duclos’ house, her closest friend and frequent castmate. When she arrived, a man dressed in a footman’s livery, whom she’d never seen before, said to her in a mocking tone: “The citoyenne Duclos was arrested this afternoon.” Guessing that he was actually a police officer, Maryse, enraged, shouted in his face: “This is what happens nowadays to decent people! I assume others of my friends have met with the same fate.”

The man, looking her lasciviously up and down, replied: “Correct, citoyenne Polidor, and if you weren’t caught in the raid as well it was only out of consideration for your mulâtre. You be careful now, and don’t go looking for trouble.”

Curled into a ball on the seat of her carriage, Maryse wept out of helplessness and rage. For the first time ever, she felt like a stranger in her own city. She felt an urgent need to hear a kind voice, feel the warmth of a caress. Crying convulsively, declaring her love amid sobs, she surprised Portelance in his nightshirt, who, as he held her tight, had absolutely no idea just how close he’d come to losing her.

When Portelance and Maryse arrived in Brest, they learned that the port authorities had prohibited all passengers bound overseas from boarding the ship. It was a preventative measure: the previous night, a special messenger dispatched by the Convention had delivered news of the events of the 9th of Thermidor, namely, that Robespierre and Saint-Just had been sentenced to death. On the way back to Paris, Portelance was stopped and interrogated about his mission and his relationship with the Committee of Public Safety, and, in particular, with Robespierre. His response was clear and direct: “For many years my sole objective has been to restore human dignity to the people of color of Saint-Domingue. If that constitutes a crime, then I am guilty.” As there were only suspicions, but no serious accusations lodged against him, he was assured that the interrogation had been merely a formality and that he should not be concerned. “Calmly return home. You’ll be contacted soon,” he was told.

But months passed, and no one sought out his services. It was true that the new Government, in altering the radical course that the Revolution had been following, now faced problems far more serious and immediate than the chaotic war in the Antilles—prices were going up, currency was being devalued, people were hungry and rebelling and the Jacobins were perpetually plotting—but it was no less true that, in the new political circles, Portelance was generally mistrusted.

However, the moment finally arrived for Saint-Domingue to return to the stage. In the wake of a series of decisive victories, the Republican armies had occupied Belgium, the United Provinces, and the German territories to the west of the Rhine. From this position of power, France had negotiated a deal with Spain: France would return the occupied territories on the other side of the Pyrenees in exchange for Spain’s ceding the colony of Santo Domingo, which bordered Saint-Domingue.

“A wise move by the Directorate. Now the entire island is Saint-Domingue. This means that colonial issues have regained importance,” said Portelance, showing the newspaper to Maryse. “If only the Directorate would consult with me. Who better than I to recommend a political course of action there?”

“My darling. I want you to know, above all, that I am perfectly happy with you and am ready and willing to follow you wherever you choose to go. But I’m concerned about your health. You don’t eat well, you sleep poorly and you spend your days waiting for them to contact you. I have promised not to interfere in your affairs, but there’s a limit to everything. I’m afraid for you, Portelance. If you continue like this, you’re going to go mad. You must do something to escape this situation.”

“Such as renounce my principles and go to live in Spain? Isn’t that right?” he said bitterly.

“It wouldn’t be all bad, but it would make you unhappy,” said Maryse, without losing her composure. “What I propose has everything to do with precisely that: your principles. You have waited more than patiently and you now run the risk of being forgotten. Why don’t you write a letter detailing what should be done in Saint-Domingue and send it to Barras or to any other member of the Directorate? Or better yet, why not request an interview?”

“Maryse, Maryse, how little you know me! I have already written three proposals and the answer is always the same: ‘We are grateful to citoyen Portelance for his Discourse on Fomenting Peace and Industry in the Colony of Saint-Domingue, which we have forwarded to the corresponding office of the Minister of the Navy and Colonies.’ And I have asked to see each one of the members of the Directorate not once, but twice. The truth is . . .”

“Then why do you continue to torture yourself?” interrupted Maryse. “If they don’t want to listen to you, it’s their loss.”

“No, it’s Saint-Domingue’s loss. France’s loss. I must keep trying, especially now that the entire island is French.”

“What are you going to do? You can’t go on like this.”

“I’m thinking of writing a book. That way I could express my political and economic ideas as fully as they require. But above all, I’ll write about Toussaint Louverture, the only man capable of pacifying and reconstructing Saint-Domingue. A black man, an ex-slave, who has proved himself an excellent military man and a capable administrator. The territories under his control are peaceful, orderly and industrious. What’s more, he’s the only one who truly understands the futility of racial wars. He knows that the only way to reestablish the island’s production of coffee and sugar is through cooperation among whites, blacks, and mulatos. I have this all from a reliable source. My brother Claude represents his business interests in Philadelphia. If our plantations were once the wealthiest in the world, there is absolutely no reason that they shouldn’t be again, especially now that slave labor is a thing of the past. But power must be in Louverture’s hands. He and he alone should be the next Captain General and Governor of the island. And when I say ‘the island,’ I am no longer referring to a colony, but rather to an overseas province with sufficient autonomy to govern itself and trade freely. If it fails to follow this course,” concluded Portelance, “France will lose Saint-Domingue.”

Maryse, moved by Portelance’s unshakeable perseverance, offered to help in any way possible: “I’ll stop taking voice lessons and cancel my commitments. Just tell me how I can be of use to you.”

They worked tirelessly for four solid months. While Portelance wrote, Maryse went to the library and copied the documents and articles he requested. But they were also in love like never before, united, for the first time, by a common purpose. When the book was finished, Portelance took it to the printer, paying twice the established rate so that it would be published immediately—the Directorate had yet to name the new Commissioners who would take charge of Saint-Domingue, and Portelance hoped that his ideas, once in print, would spur them to bring him on as an advisor.

When the book was published, Portelance followed Maryse’s advice and invited a group of friends, politicians, and journalists to a grand dinner. Only a very few accepted, all of them Jacobins. At that moment, he realized that his dealings with Robespierre, limited though they had been to issues concerning Saint-Domingue, had been misinterpreted. “They take me for a Jacobin, plain and simple, a spy for Robespierre,” he told Maryse bitterly. “Now I know the reason they have marginalized me. No one will read my book. All our work has been in vain.”

A few weeks later, the newspapers published the names that would comprise the Commission to Saint-Domingue: Sonthonax and Roume, on the civil side; Rochambeau, on the military. There were also members of lower rank. Upon reading the name Julian Raymond, his old ally from back in the days of the Amis des Noirs, Portelance commented sarcastically: “At least they named a mulatto.”

“Listen, love,” said Maryse, bound and determined. “What’s stopping us from boarding the same ship as the Commission and traveling to Saint-Domingue of our own accord? Don’t you own property there?”

“It would be pointless. I have no official title to back me. If I meddle in their politics, they’ll turn against me. No, my love, now is not the moment to travel. But mark my words,” he added, smiling, “that day will come.”

And, in time, the day did come: through his brother, Portelance would receive the incredible news that Louverture had learned of his book and wanted him at his side without further delay.