Читать книгу Secrets of Giron Arnis Escrima - Antonio Somera - Страница 11

ОглавлениеPart One

Background

and Overview

1

Development of a Fighting Art

The history of the Philippines and her martial arts is a history of influences whose origins span the globe—extending from the Malay Peninsula, the Indonesian Archipelago, China, India, Japan, and the Middle East, to Europe and the Americas. These regions have made an impact on the Philippines through centuries of trade, migration, and conflict. The blood and ashes of such conflict has marked the landscape and national psyche of this great land for over one thousand years. This has involved a virtual kaleidoscope of cultural, ethnic, religious, and linguistic backgrounds. Throughout the ages, the people of these islands have observed, learned, and adapted from others where necessary while reinforcing and refining the wealth of indigenous knowledge already in place.

Regionalism

Regionalism in the Philippines evolved from the ancient barangay system of rule where rajahs or kings would exercise direct authority over a virtual city-state, consisting of between thirty and one-hundred families. Often, barangays with common language and customs would confederate with others, forming much larger regional kingdoms. This eventually formed the political-geographic basis of what has become today’s provincial system of government. It was during the period of regional kingdoms that the Spanish first arrived.

As if in a classical morality play, the symbolism of certain events often looms larger than the occurrences themselves. The defeat in 1521 of the Portuguese explorer, Fernando Magallanes, or Ferdinand Magellan as he is known today, while sailing under the Spanish flag, indicated such an event. While attempting to bring the rajah and datus (chieftains) of Cebu under Spanish control, Magellan foolishly assumed a lack of martial capabilities among inhabitants and blundered into a conflict which ultimately led to his demise. His nemesis was a king by the name ofLapulapu. Rajah Lapulapu was named after a colorful and aggressive coral game fish of the area. Lapulapu was not of the people commonly settled in the larger island of Cebu. He was of the Orang Lauts, or man of the high seas, from the southern Celebes.

Magellan had unwittingly encountered a fierce people whose lives were dedicated to freedom and struggle. Magellan’s defeat at Mactan became a symbol representing the inherent power of the people to resist the imposition of foreign rule. It is both ironic and illuminating that notwithstanding the long period of the Spanish rule, some 333 years, a short-lived American period, and an even briefer Japanese occupation, it is the event of victory that stands out when characterizing Filipino history. What Magellan failed to understand was that he was dealing with a people of great variety and complexity who were not unprepared for his challenge. Lapulapu and other leaders of common ancestry and experience shared a tradition of acculturation which included the study and training in the arts of war as well as other facets of life. These martial arts have continued to evolve, resulting in many of the styles and systems found in the central and southern regions of the Philippines today. In some parts of the Visayas and Luzon, knowledge of European fencing techniques generated counter measures to be woven into the fabric of indigenous styles and systems. Examples of successful resistance to foreign rule as in the case of the unconquered Moros of the southern Philippines, further served to encourage the spirit of independence among all peoples of the islands. This spirit frequently surfaced as full-blown revolts throughout Philippine history.

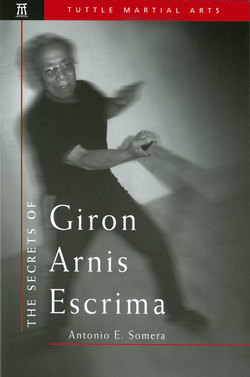

Grandmaster Giron with a panabas

Some ninety years later in a much different part of the islands, it was just such a revolt that proved to be a pivotal factor in the further development of the Filipino martial arts. The location was Pangasinan, Grandmaster Giron’s home province. In 1660, a local leader named Andres Malong proclaimed himself king and mounted a popular but short-lived revolt against Spanish rule. Governor Manrique de Lara learned of the rebellion through the capture of a letter from Malong to Don Francisco Manago. The subsequent suppression of this revolt by Spanish forces, in addition to the capture and execution of Malong, led to a scattering of former rebels under arms into the surrounding hills. From these areas of relative security, members of the disbanded units resorted to banditry, preying on local farmers and villagers. Just as the people of the south in an earlier time were not unprepared to meet the challenge of oppression, these local inhabitants banded together in common defense. For centuries, there had been many personal combat styles commonly employed in this region, all with some general relationship in terms of type of weapon, style of movement, or proximity to an opponent. During this time, however, there developed a “new” style named cabaroan.

Cabaroan was well suited to the working farmer or villager who could not devote long hours to training in the traditional short-weapon, block-and-counter styles of more experienced fighters. This new style which is now more commonly described and referred to as larga mano (or long hand), was developed through the successful use of the panabas and other similar bladed tools used for the clearing of brush or agriculture.

In general, the panabas consists of a twenty-inch blade attached to a twenty-inch bamboo or wooden handle. Although the use of farm implements as a means of self-defense is by no means unique to Luzon, the specific method of employing these tools is what characterizes the larga mano style. The fundamental essence of the style is found in its concepts of fighting range, economy of movement, and its ability to blend with the older styles of arnis and escrima. From this point on both the “old” (cada-anan) and the “new” (cabaroan) escrima and arnis styles continued to grow, often in unison. In fact, Grandmaster Giron, a native of Bayambang, relates that “there eventually came a time when if one was asked what style he played, and he answered both old and new, you would then see the inquirer’s tone and general demeanor turn less arrogant, with words carefully chosen to deal with the developing situation.”

The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

The history of resistance and revolt continued throughout the Philippines for the next two centuries. The successes of the Spanish colonizers during this period may largely be attributed to specific policies which included the use of Spanish or peninsular friars to instill the fear of the Divine against rebellion. In addition, a divide-and-conquer strategy employed peoples of one Philippine region or ethnic background to suppress the revolt of another. This two-hundred year cycle was broken by another Spanish blunder, the martyrdom of three secular or native Filipino priests who were not affiliated with the Spanish friars. In an attempt to discredit the development of an independent priesthood in the Philippines, Spanish authorities exposed the political link between the friars and the government. In 1872, during what may otherwise have become simply another footnote in the history of local revolt, native members of the militia in Cavite province rebelled against additional taxation of their pay vouchers. Authorities seizing upon this as an opportunity to accuse and discredit secular native priests in some unspecified conspiracy, arrested, secretly tried, and executed the three local clerics Fathers Gomes, Burgos, and Zamora. This event served to alienate many citizens from the established Spanish church and became a unifying event for those who began to seriously consider independence. Filipinos were well aware that the independence of Mexico in 1821 began with the actions of the Creole priest, Miguel Hidalgo, in 1810. Cavite thus became another focal point in history, symbolizing the divisions between the colonial authority of Spain and the naturally assumed rights of all Filipinos. At this moment, the quest to be nationalized was prevalent.

It should be noted that during the later part of the nineteenth century, Spain itself was undergoing a period of political turmoil. Much of the Spanish empire in the western hemisphere had vanished under a wave of independence movements. One hundred and sixty thousand Spanish troops were required to deal with 40,000 insurgents in Cuba. Moreover, and the Spanish government under the regency of Maria Cristina was deadlocked and suffered from corruption within. Various conflicting groups were seeking alternatives to the stagnation of a strong monarchy, constitutional parliamentary monarchy, other forms of democratic rule, regional autonomy, and freedom for territories abroad.

One element that played a role in this mix of ideas and opinions was the freemasonry movement. Influenced by the anti-monarchical, anticlerical upheaval which occurred in France during the latter part of the eighteenth century, freemasonry became a vehicle throughout Europe and its colonial possessions for secretly organizing individuals opposed to the traditional partnerships of church and state. Given the widespread negative reaction to the executions of Fryers Burgos, Zamora, and Gomes, a strong attraction toward these secret societies took place in the Philippines.

The political movements in both Spain and the Philippine Islands found common interests, but at the early stages did not appeal to a wide range of citizens from either country. In 1888, the Hispano-Filipino Association and the newspaper La Solidaridad were established in Barcelona, Spain, later relocating to Madrid. Under the protection of the laws of association in Spain surfaced the names of Serrano, Ramos, Luna, Lopez, Rizal, and Pilar. Jose Rizal returned to the Islands in 1892 and before being exiled to Dapitan, Mindanao in 1893, succeeded in organizing the beginnings of La Liga Filipina, based upon Masonic organization and nurtured by the writings of La Solidaridad. La Liga Filipina soon gave way to a new organization as earnest attempts were made to broaden the base of support for independence. Thus, the Katipunan (revolutionary brotherhood) was formed under the guidance of Macario Del Pilar in Madrid, and the more direct leadership of Andres Bonifacio, Ladislao Diva, Teodoro Plata, and others. By 1896, Katipunan membership in Manila and its provinces alone exceeded 14,000 with no less than 20,000 others residing in Cavite, Batangas, Laguna, and Nueva Ecija provinces. Additional members were spread throughout Luzon.

The Symbols of Unity

This moment in time brought together a convergence of ideas, opinions, and interests, however varied, upon the one unifying concept of independence, and with it all of the symbols of a culture striving for common expression. The initiation rite of the Katipunan highlights the importance of the triangle, the light of candles, and the pacto de sangre (blood oath). It is among such symbols that we see intertwined in the soul of the martial arts and the soul of the people.

The triangular footwork patterns carefully developed and perfected by practitioners of escrima and arnis had already been interwoven into the Filipino mind and spirit through generations of symbolism representing the unity of such district components as the three major island groups which together form a nation, or the three major cultural religious influences Christianity, Islam, and animism.

Despite a great variety of techniques and styles of movement, a preponderance of Filipino martial arts closely link or encompass the triangle within a circle. This symbolically associates the finite with the infinite, the linear with the circular, the physical world with the spiritual, beginning and ending with that which is constant. This infusion of opposites becomes a Philippine equivalent of the Taoist concept of yin and yang, or unity of opposites. In politics or warfare, as in other forms of human organization, the group is represented by the circle while the pursuit of objectives is represented by linear action.