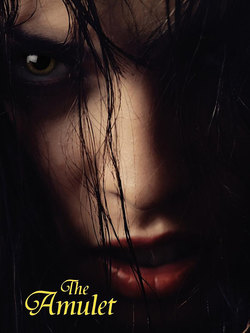

Читать книгу The Amulet - A.R. Morlan - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

Prague, Bohemia, Late October 1880

Night Skirt

Chill wind scattered blown leaves along the lamp-lit cobbled street outside Karel Nezval’s diamond-paned front parlor window. An occasional clawed leaf raked the window glass with a faintly chitinous sound, disturbing Nezval’s sensitive ears. He paused to rub the shell-curled surface of his left ear as he read his archaeologist friend’s latest letter, which had arrived simultaneously with a small wooden box carefully wrapped in oiled paper and thin but incredibly strong twine, said box also sent by his boyhood friend.

Shifting his slightly protruding, yet deeply hooded brown eyes away from the fine feathery tracery of Josef’s penned words, the glass manufacturer (and armchair Egyptologist, a holdover from his student days in Berlin) glanced at the opened wooden box, which rested on the small, round cherry wood table near the hissing and sputtering fireplace. The box itself was propped up slightly, the upper end resting on the box lid, so that Nezval could better view the small treasure Josef Zeyerhad so recently freed from Egypt’s sandy soil. The deep yellow-gold and green basalt surfaces of the object were warmly illuminated by the red and orange tongues of flame in the fluttering fire. Nezval leaned across the left arm of his chair and squinted as he admired his unexpected gift from Josef—the delicate, almost impossibly fine detailing, especially on such a small piece of jewelry; the way the scales on the lower half seemed to strain through the oily-smooth skin of the thing, as if originating from within the gold, and not merely molded or incised upon it.

“Beautiful,” Karel Nezval whispered, his tongue darting out to almost touch the deep indentation of flesh under his lower lip, before he reluctantly returned his gaze to Josef’s letter:

...most unusual sort. As you see, the end with the serpent head is not fashioned of red stone, paste, or jasper at all, as is fitting for a symbol of the snake goddess Isis. I do not know for certain, nor do I wish to know, dear Karel, what the maker of this amulet had in mind when he cast the serpent in gold, but according to the hekau inscribed on the underbelly (what I have been able to translate of them), he was seeking power greater than that of a scarab alone, yet not necessarily the customary one of a serpent’s head-to protect the deceased from the bites of the snakes in the underworld. Instead, he sought deviating powers, whose range and intensity are most intriguing, albeit thoroughly atavistic, and most genuine, as I myself can attest.

This is why I have sent the amulet to you for safekeeping—the natives in our camp fear it, with good reason, and those of us in charge of the excavation respect it mightily. But it has proven too much of a temptation for us, dear Karel, which is why I have entrusted it in your care. I implore you to heed the warning enclosed in the box, and written at the beginning of this letter: do not touch the amulet with your bare hands, or with gloves, unless they are of asbestos. Use the tongs provided in the box, or tweezers, if you have them.

Please heed me in this, Karel. One man, a native worker, died as a result of the power of this piece. We killed him out of necessity, before he killed us and demolished the entire dig. The hekau inscribed on the amulet (and, I suspect strongly, amplified by more “words of power” uttered over the amulet upon completion) are, as far as I can tell from a limited translation, most detailed and specific, with the most malicious of intentions.

Imagination fails when I attempt to envision the master plan of this object’s maker. One of my colleagues, Herr Dobbershutz, has surmised that the maker of the amulet introduced quicksilver or some similar alloy in the casting of the gold, and added the ground up bodies of a real scarab beetle and a serpent to the crucible. Upon witnessing the unfortunate state in which our native man met his demise, I find myself in agreement with Herr Dobbershutz. Words of power alone do not account for what happened when that fellow held the amulet.

Dear Karel, if you can further decipher the hekau on this amulet, please do so. But, I implore you, remain cautious in all your contact with it. I knew not where else to send this entity, to keep it in safe, sober hands. I hope that by removing the piece from the land of its origin, I have somehow negated even a small fraction of its powers.

Karel Nezval let out a soft, barking laugh as Josef’s letter spiraled to the lush carpet below with a dry flutter of stiff rag paper. After poking the logs behind the grate until they sent upsputtering points of light, like a miniature meteor shower inst the sooty bricks of his fireplace, the owner of the third largest glass-making factory in all of Austria-Hungary rubbed palms together with a dry snicking sound and said aloud, not caring if his cowed servants heard him or not, “Poor Josef—always acting like a hysterical woman. Even as a boy...and now as a man, if ‘man’ I dare call you, my friend.

“A native lackey goes on a rampage, and my poor Josef is shaking in his drawers, blaming a trinket of gold alloy. Josef will believe me when I tell him that I simply had to dispose of the amulet, for his own safety. He would never dream of asking me where or how, or impose on me to show him the contents of my safe. Trusting, unquestioning Josef—”

“You called for me, sir?”

Summoned by the sound of her employer’s voice, Nezval’s parlor maid now stood in the doorway, her reddish-brown upswept hair a blaze of burnished copper in the fireplace’s still low-burning light. After giving his excelsior-bedded golden treasure a final, longing glance (later, later, I will discover what Josef was so intimidated by, he thought), Nezval turned his attention to the young woman waiting next to the opened door, admiring the swells and valleys of her as-yet-unused body under the prim white aproned black uniform, the metallic gleam of her coiled reddish hair, until he hit upon the best mode of attack, of getting the most service for the money he paid the girl. He said nonchalantly, in a tone that belied the growing tumescence in his lower regions, the eager anticipation tingling in his hands, his lips, “Yes, Anna, the fire needs tending,” then waited, his insides already aflame, until the tall, buxom maid had crossed the parlor, with a gentle sighing swish of black wool brushing against starchy petticoats below, on her way to the fireplace. And when she had her back turned to him, Karel Nezval was able to shut and lock the thick oak parlor door, unnoticed by his obedient parlor maid.

October 1931

Lucy’s bare feet made soft slapping sounds on the dusty plank floor as she made her way down the upstairs hallway, heading for the staircase. Her cotton nightgown brushed against her calves, almost making her giggle, but she curled her lower lip between her teeth and bit down hard, telling herself, Gramma doesn’t giggle when her night skirt brushes her legs—she just lets it trail out like twilight, all dark and deep and wide behind her. Lucy always tried to be like her grandmother, even though her blue serge middy skirt only came down to her knees, and the blue wasn’t blue enough—not that rich, plum-like blue-black of Gramma’s night skirt, with the star-like twinkle of lacy petticoat peeping out from under the thick rolled hem when she walked.

Gramma had been everything to Lucy, for all of her six and a half years on earth, just as Lucy was everything to her mother’s mother. Ever since Gramma’s big house with the gingerbread trim on the roof overhang and big curved porch was taken away by the county (Mother said it was all President Hoover’s fault, “For getting us in this mess,” but Lucy didn’t think that her Gramma even knew the president), Gramma had lived in Lucy’s house.

Downstairs, because climbing the stairs was too hard for a woman with too-white hair and soft, puffy, dotted arms, and teeth that could pop out of her mouth. But Gramma’s age wasn’t the only reason she slept downstairs. Lucy wasn’t supposed to know any of this, but like maiden Aunt Dora said, little pitchers have big ears, and Lucy couldn’t help it if her room was next to Mother and Daddy’s.

“Couldn’t she live somewhere else—anywhere else?” Mother had said to Daddy many a time after Gramma swept into their house and settled down in the sewing room off the kitchen, And Daddy’s answer was always the same: “She’s your mother, you’re her daughter, and you happen to be an only child. Where else is she supposed to go?”

And Mother’s answer was always the same, too. Never answering Daddy, she’d almost sigh, “I wish Lucy hadn’t attached herself to her like a barnacle on a barge. It isn’t healthy.”

“Your mother did all right by you—you turned out swell. Why shouldn’t Lucy be fine?”

There was always a pause there, as if Mother wanted to say more, but couldn’t or wouldn’t. Then: “But those were different times. When I was small every mother wore long swishing skirts and tucked lace hankies in their sleeves. It’s 1931—she shouldn’t be dressing like that. And don’t tell me I should buy her a dollar cotton pongee dress from Sears and burn her old things. Oh, I know that’s what you were thinking, and it wouldn’t work. My mother has worn a long black skirt for ages—since before Poppa died. And I do believe she will die in that awful thing. What’s that Lucy’s taken to calling it—night skirt? Some such silliness—and she fosters it. I won’t stand for it, the way she addles poor Lucy’s mind. It’s bad enough we’re old—”

“Old? I feel pretty fit for—”

“Fifty. And I am forty-five. Perhaps having a baby so late wasn’t the ideal thing to do—after all, my mother is in her seventies.”

“Oh, you worry too much,” Daddy would always end up saying, before turning over in bed and making the old spring mattress creak and groan like a withered tree in a thunderstorm.

Lucy could almost feel her mother’s anger seething out of her, through the wallpaper and plaster of the wall between their bedrooms, and into her. She imagined her mother’s displeasure as something cold-bright and pulsing, like the full moon swimming in a foggy sky.

Arid as she lay in her too-short bed, her feet poking through the white enameled spindles at the bottom, Lucy wondered if Gramma could feel Mother’s seeping anger dripping down on her, through the floor to the sewing room below. Gramma often told Lucy that grandmothers have a way of knowing all sorts of things. And since Lucy’s other grandmother and both her grandfathers died back in 1918, during the influenza epidemic, Lucy took her Gramma’s word for it.

After all, Gramma wore the night skirt with the star-sparkling white petticoats, while Lucy’s mother only wore a rayon slip under short cotton and pongee dresses. And didn’t Gramma sit Lucy down on her big lap and whisper in her ear that short dresses were bad—that they weren’t special, like the rippling soft and oh-so-dark-it-sucked-in-the-light night skirt?

Once, Lucy had tried tying her winter coat around her waist, using the sleeves like apron ties to keep it around her body. But even though the coat was blue-black wool, it just wasn’t the same as Gramma’s night skirt. The ripple of the material wasn’t there, and neither were the other things. Hadn’t Gramma laughed when she had seen Lucy strutting around in her thick, ersatz skirt?

Bending over to scoop Lucy up in her plump arms, she’d whispered in the girl’s ear, “Is my Lucy trying to wear a night skirt? Oh, Lucy, Pumpkin, Gramma’s night skirt is very special—not for little girls. Oh no, no, no.” But when Gramma said, “No, no, no,” it didn’t sound like it did when Mother said it (as Lucy slapped down the uncarpeted stairs, her small mouth twisted like she’d just tried to eat a peeled lemon), oh no, not at all....

And hadn’t Gramma shown Lucy how special her long blue-black-purple skirt could be? There was that time in the front yard, in winter (the most special, secret time, when Lucy swore on her heart and hoped to die that she wouldn’t tell Mother or Daddy what she’d seen), and the other time, when Lucy had scooted along the floor while Gramma was napping she’d lifted up the hem of the night skirt and curled up in a little ball under the heavy fabric.

As she made her way down the stairs in the darkness of evening toward Gramma’s room, Lucy remembered how she had been able to see only a faint haze of light, like trying to look through the stacks of screen windows resting against the house, the day Daddy changed the windows in early summer. But the more she’d looked, the better she could see—only through the cloth of the night skirt, things looked different. Colors changed, and the shapes of things, too. At first, Lucy hadn’t recognized Mother at all, for seen through that night-dark fabric, Mother was a horned, angled creature, all hard surfaces and spikes.

That was when Lucy whimpered, and Gramma nudged her out from under the night skirt and had Lucy on her lap before Mother could open her thick lips to scold or complain. But Lucy saw the look in her mother’s hazel eyes, and almost imagined the horns again. And for many a night after that.

Mother told Daddy in the half hour or so before sleep overtook them that she ought to take Gramma’s “damned skirt” out and burn it—just toss it on the trash heap and incinerate it. Lucy wondered why Mother didn’t suggest giving the skirt to the woman who came around every week, but every time Mother mentioned it, all she seemed to think of was destroying it.

Lucy was careful not to make the treads squeak as she went down the stairs, even though she could hear the loose flutter and harsh blap-blap-blap of her parents snoring above. She held onto the big thick railing that was almost level with her shoulders, her slightly damp palm sticking in places to somewhat gummy old varnish of the oak rail. Down below, moonlight came through the shaded and curtained windows in hazy patches, just the way the light had been filtered through Gramma’s night skirt, only different, too. It was hard for Lucy to put into words, but the mind-picture came easily enough along with other pictures, from other times with Gramma. Like last winter.

Reaching the cool first floor, her bare toes feeling cautiously for any sharp things like gravel or splinters on the varnished wood surface, Lucy slowly made her way, hands outstretched, toward Gramma’s room. As she did so, the memory of another walk, this time over snow and cold cement, came back to her.

Gramma said she didn’t like going outside in the snow—she might slip and fall and break her brittle bones—but Lucy’s birthday was coming up next week, and Daddy had forgotten to mail the invitations for her party when he had left the house that morning. Mother was busy ironing clothes, making puffs of whitish steam come up with a hot fabric smell off the ironing board set up in the kitchen, so Lucy begged and begged until Gramma said she’d walk down the street with Lucy to the mailbox, and drop the tiny stamped envelopes into the slot that Lucy couldn’t reach herself.

But Lucy could tell that Gramma wasn’t too keen on the idea, even though she said nothing to Lucy as she held her hand, which poked out of the fur trim on her winter coat. Lucy was so happy to have her invitations mailed that at first she thought Gramma would get over being upset.

And maybe Gramma would have been just fine, but Lucy shook her hand loose from Gramma’s kid-gloved grip and began walking backwards, like Vernilla Nemmitz in school did at recess time. Gramma began to cluck and scold softly, telling Lucy, “Oh, Pumpkin, little ladies don’t walk like that!” But Lucy was thinking that come Monday she’d show old “I’m in-the-second-grade” Vernilla what she could do, and then she looked down at her faint footprints in the sugary dusting of snow, and her grandmother’s, and stopped in her tracks, one tiny gloved hand pointing, just pointing down at what she saw.

That was when Gramma reached out and took her hand and steered Lucy back to the house, leaning down every once in a while to whisper something fast and quiet to the little girl, until Lucy began to nod in awareness. Near the front porch, Lucy solemnly crossed her heart and hoped to die rather than tell anyone, even Vernilla Nemmitz at school, what she’d seen in the fast-melting snow.

Other grandchildren might have been scared after seeing what Lucy had seen, but she loved her Gramma, and the deep, pitch-black secrets of the night skirt, and in return for promising never, never to tell, Gramma had made a promise to Lucy, too.

Her breath billowing out in small, semitransparent white clouds before her gently sagging face, Gramma had whispered with soft popping clicks of her false teeth, “Someday, my little Pumpkin, you’ll get to wear the night skirt, too—not your mother, but you. Your mother doesn’t understand—not like you, my girl.”

And even though Lucy really didn’t understand everything just yet, she’d nodded in agreement. A few weeks later, she’d tried making her own night skirt out of her coat, making Gramma laugh. That was when she’d said the night skirt wasn’t for little girls-at least, not yet.

But as Lucy made her way toward the doorway of Gramma’s room, now keeping her arms at her sides so she wouldn’t knock over Mother’s bric-a-brac stand with a thump and a crunch and a delicate shatter, she told herself that now she could wear the night skirt, that Gramma surely understood, even if she wasn’t alive anymore.

Lucy had been what the neighbors called a “brave little girl” when the doctor came out of Gramma’s bedroom-cum-sewing room that afternoon, closing his black leather bag with a snapping-fingernails click that made almost everyone in the parlor jump in place and twitch their closed mouths before they cast their eyes to the floor and began to pat Mother on the back with gentle hands. Even without being told, Lucy knew what had happened, and without needing to ask, she’d known that the night skirt was now hers.

Gramma had said so, hadn’t she?

For on that day, Lucy had seen footprints that weren’t always footprints trailing out behind Gramma, even though she had been careful not to step on the snow if she could help it, instead searching out the bare spots on the cold cement...but in some places there was nothing but snow, and in others, Lucy had seen the rounded arches of hooves, the four-toed round pads of cat paws, only really big, and the thin skitterings of bird claws, and here and there a regular shoe print, but only here and there.

All the funny tracks in the snow trailed out behind Gramma’s wonderful, terrible, oh-so-thick-and-dark night skirt, dusted here and there by the sweep of the trailing skirt, but not obliterated.

And Lucy had been a good girl, keeping the secret she’d exed into her breast with trembling fingers. And without being told she’d kept secret what she’d seen through the night skirt—that angular place that wasn’t Gramma’s room anymore, with that homed, strange thing that was but wasn’t her mother.

When Gramma had nudged her out from under there, Lucy had felt sharp claws at her back, poking through the wool jersey of her dress, and the lashing curl of a tail whip around her arm, but she hadn’t told about that, either. For even if she hadn’t liked her Gramma, and had run screaming for her mother, begging her to look, Gramma would have had normal feet tucked in normal dark stockings and sensible leather shoes, for that was part of the mystery of the night skirt, that keeper of the dark, and all that crept or crawled or prowled under cover of darkness.

The mystery and magic of the wonderful night skirt, and of the secrets that Gramma promised to tell Lucy, “later, when you’re a big girl and can wear the real night skirt,” only “later” was now, and Lucy was a big girl, almost seven, so she figured that that was big enough to wear the night skirt. To use it, like Gramma had used it.

For hadn’t the men from the county who took away Gramma’s house gotten all tumbled and broken when their Ford went into that ditch last fall? True, Gramma’s big fancy house was sold by then, to those nasty Parks people, but hadn’t Gramma had a big smile on her weathered face while she rocked after hearing the news about the car accident from Daddy?

Even though Mother and some of the ladies from the neighborhood had come into Gramma’s room and washed her, before setting the damp cloths on her now slack face and folded hands, they hadn’t taken away the night skirt. They hadn’t thrown it on the trash heap and burned it to a cinder, like Mother kept saying she wanted to do, even though the skirt was Lucy’s now.

Maybe Mother didn’t want the other ladies to see her do a mean thing like that, Lucy said to herself as she paused at the closed door of Gramma’s room. That her Gramma was dead didn’t bother Lucy much, at least not in the way it might have bothered other little girls who loved their grandmothers. Because her Gramma had told her things—oh, lots of good stuff—when Mother wasn’t listening. And even though Gramma had been caught by surprise when the mean men from the county took away her house, and hadn’t been able to make the night skirt work for her then, she’d still gotten something called revenge on them all. And she had chuckled and hugged Lucy tight when she had said that, and all Lucy could think was, When I get the night skirt. first I’m gonna show old Vernilla some really fancy walking, and then I’ll....

But up until yesterday, when Gramma’s lower tummy got to feeling had, and Mother all but tore the night skirt off her, saying it was so she could get a nightgown on Gramma (but Lucy knew what her mother was really thinking when she pulled the skirt off the protesting old woman), Lucy had always thought of “and then” as being a long, long time away. Like next year, or longer.

Rut when Lucy had heard Gramma’s whimpers from under the closed door, while Daddy rang for the doctor, then the neighbors, Lucy had realized that the time of the night skirt flapping and flowing and dragging around her legs had come at last.

And as much as losing Gramma hurt, Lucy was all antsy inside during the rest of the evening, until the time when she beard her parents’ last faint words coming through the wall (“And first thing tomorrow, that skirt goes out the door, you hear me, Alvin?” “Uh-huh....”) and then only raspy breathing. And now, she had her small finger wrapped around the doorknob, the metal cool and just the faintest bit greasy. Slowly she turned the knob until the door swung inward, into darkness even deeper and thicker and softer than the night skirt itself.

Gramma was in there, in the almost solid blackness. Lying on her bed, a drying cloth over her face and hands, even though it wasn’t nearly warm enough to start worrying about that sort of thing yet. Lucy was glad that Mr. Byrne and Mr. Reish were both down with the grippe. Otherwise, the two undertakers might have come and taken Gramma away, and mother might have tossed the night skirt into the backyard trash bin, where any animal might have slithered or crawled into it—and Lucy didn’t want to think about what might happen then!

Her eyes were more accustomed to the dark now. She could faintly see the two pale places where the damp hankies rested on her Gramma’s face and hands. Which meant that if the bed was there, the rocker where Mother had placed the folded night skirt had to be right here.

Like a slumbering animal awakened by the gentle, loving touch of its owner, the night skirt rippled under Lucy’s small fingers. Darker than the surrounding darkness, the night skirt felt as warm to Lucy as if her Gramma had just removed it only moments before.

Feeling for the opening with her hands, Lucy opened up the waistband. After tucking her nightgown around her legs (it would make a good, if makeshift, slip), Lucy stepped into the night skirt, rolling the fabric up and up, until the skirt’s hem dusted her insteps. After patting the seat of the rocker, Lucy found Gramma’s belt and tightened the stiff strip of fabric around her waist, her arms hampered by the thick roll of excess cloth scrunched up under her armpits. But Lucy didn’t mind that at all; as Gramma told her, she was going to be taller someday.

Relishing the heavy swish of fabric around her thin legs as she walked, Lucy paused by her Gramma’s bed, whispering, “I’ll come and make you better in a little while—after I come back from their room. Then we’ll play, okay, Gramma?” After giving the still hands and face a cloth-screened pat, Lucy left the room, heading for the staircase.

The cloth of the night skirt made a faint, susurrus noise that almost masked the delicate click-click of claws and scrabbling scritch of talons as Lucy made her determined way across the carpetless floorboards. But as she mounted the first stair tread, her skirt brushed against the next step up, and even the muted swish of the fabric couldn’t cover the thump of something hard coming in contact with soft wood.

Lucy bent down and felt the hem of the night skirt, feeding the rolled material through her damp hands until something long and hard and bumpy slid through her fingers. As she probed the bunched fabric, the hard shape moved, first rippling, then curling in on itself as the little girl smiled in the moonlight-splashed darkness and whispered, “Gotcha.”

Tongue pressed between her tiny teeth, Lucy worked the heavy thing toward the sewn edge of the hem, where the stitches were...and where the threads finally broke. And as Lucy extracted the oily-warm thing from the hem of the night skirt, the belt around her waist came undone, letting the night skirt drop to a cold, musty heap on the floor. Stepping out of the skirt, the special thing trapped in her sweating palm, Lucy felt nothing but limp nubby cloth under her feet...nothing more. The skirt no longer rippled, nor did it suck in the darkness anymore.

But the coiled object in her hand was warm, writhing, as she stroked it with a tiny, short-nailed finger. She thought, I am a big girl now. I know the night skirt’s secret, and nobody had to tell me, either.

The tiny entity curled in her palm made Lucy feel fizzy-funny inside, like her insides were all jumbled up, but it was such a nice feeling, too. And then, realizing that what she was going to do to Mother and Daddy could wait awhile, she hurried back to her Gramma’s room, her vision suddenly different in the gloom, thinking, Now we both can have some fun. I want Gramma to watch me when I get them upstairs.

In her excitement, Lucy didn’t notice as her wing tips brushed Mother’s bric-a-brac shelf. Small china and glass things shivered and chattered in dumb anticipation on the polished mahogany shelf, waking Lucy’s mother in her room upstairs.