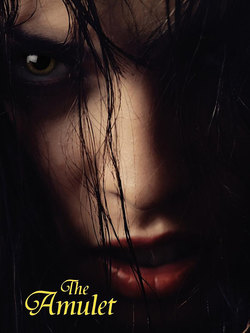

Читать книгу The Amulet - A.R. Morlan - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

Tuesday, October 20, 1987

ONE—Bib (1)

As Anna heard the car pull up and come to a stop behind her, and saw the shadow of the gumball machine on top of the vehicle, she thought, Why me, huh? Terry Von Kemp two days in a row is too much to—until she heard a different, more nasal voice ask:

“You’re Tina Miner’s girl, aren’t you?”

Anna’s hand stopped in mid-grasp around a half frozen grapefruit in the IGA dumpster. Bib Stanley was speaking. He was Ewerton’s chief of police, up until now only a disembodied voice to Anna, whose prerecorded warnings about skateboarding on the sidewalks and driving through the city parks played daily on WERT, AM and FM. Anna hadn’t even realized that he pulled patrol duty like the other officers.

Not thinking it proper to turn around to face the chief with garbage in hand, Anna reluctantly let go of the grapefruit. She couldn’t do anything about the other five already in her bag. If Chief Stanley didn’t like it, he was welcome to make a reservation for her in the vertical-bar suite of the Ewerton Hilton.

“Uh...yeah. Yes. I’m her daughter, Anna Sudek.”

“You married?” Chief Stanley had the interior lights turned off. Little of the light from the wall-mounted flood above the Dumpsters reached his face or body, save for a wedge of beard-stubbled chin.

“No. My mother was, though.” Chief of police or not, Anna didn’t feel the man was entitled to insinuate that her mother was as morally loose as the old lady considered her to be.

“Oh, yeah. I forgot about it. Been so long since I’ve seen Tina. She and I went to school together, y’know.”

“She never mentioned you to me,” Anna began, before she realized what her words sounded like. But if Stanley was offended, he said nothing about it. Instead, he said, “What I was meanin’ to ask was, are you makin’ out okay with your mom gone.”

You weasely fuck, you, Anna thought as she leaned over to pick up her mesh bag of fruit and used cake pans. Why didn’t you come right out and tell me you knew all about me and Ma?

“I’m doing fine. As you probably already know,” Anna said evenly, making a move to walk away. Stanley didn’t say anything until she was abreast of the front passenger window. Then Bib rolled down the automatic window on that side and leaned over, turning on the interior lights. In the faintly yellowish light, every hair of his five o’clock shadow stood out in three-dimensional relief, and the dry wrinkled pouches under his light brown eyes were elephantine. Anna didn’t think he looked the way he should have, based on his voice alone.

“Got a minute, Anna? I...I didn’t mean to come on like a bad cop before—I was just curious how you’re making out. I mean, with your mom gone, that leaves you with your grandmother, and—”

“Yes, a lot of people are worried about me,” Anna said, her voice belying her sarcastic intent. “And yes, I know I have to take care of the old lady. I’m seeing her later this morning. In case you’re curious, she’s taking Ma’s departure with her usual aplomb.”

“Y’know something, Anna? With smarts like yours, you’re really wasted out here. Went to college, didn’t you?

“Okay, I know you did, considering that you made it out of Ewerton once, you shouldn’t have come back here—you or your mom either. Y’know that your grandmother isn’t as helpless as she makes out. Not to speak ill of your kin, but she’s been that way—y’know, sorta helpless—for as long as I remember, and I’m forty-six. She wasn’t too old then, either.”

“My grandmother is old, Chief Stanley. Age doesn’t have anything to do with it when it comes to her. I think she relishes being old.”

“Well, that’s her affair. She seems to like it here. Things always had a way of rollin’ off her back—not like with you and me. I remember, when I was in school with Tina, how the kids—”

Jiggling her bag, Anna began to walk away again, saying, “It’s been really nice talking to you, but I have an early morning job, and I have things to do before then.”

Bib Stanley slapped the top of his dashboard, exclaiming, “That was it! I almost forgot. Would you be interested in a job that pays better than what you’re making, and for about the same amount of time?”

Really been checking up on me, haven’t you? Next you’ll be telling me when I have to take a shit, Anna mused, before she said, “I don’t think so. I’m happy where I—”

Bib was scribbling something in his notepad as he said, “You give this to Marv down at the CEP office—you can type and file a little, can’t you?—and tell him I sent you.” He extended the ripped-out page through the window. Anna made him wait a beat before reaching out to grasp it. In small, crabbed handwriting, Bib’s message said, “A. Sudek—the clerk-matron position at the police office—Brian Stanley, C of P Ewerton.”

Anna put the slip of paper into her top jacket pocket, then zipped it shut before asking, “Why the sudden interest in my welfare, Chief? Atoning for old sins?”

Bib leaned back in his seat, arms crossed behind his back. “Feisty little chit, aren’t you?” he asked without rancor.

Not quite sure what a “little chit” was, Anna replied, “Not without reason. If I wasn’t, I’d have been eaten alive out here, and you know it,”

“Yeah, I know it.” Bib yawned and scratched his head under his cap; the bristling sound was loud in the darkness. “Just like I also know that you and your mom have no chance here. It took Tina a while to wise up and get out again, and I don’t think she’s as savvy as you are, is she?”

“You’re the expert on my family,”

Bib slapped his thigh, exclaiming, “Ye gods, you’re a pip. You could have tamed some guy but good, y’know that?”

“Not when they think killing might be catching,” she replied evenly, speaking the very words her own father had used against Ma—or so Ma and the old lady often told Anna, while she was growing up.

“Well, not some guy from out here, but some guy, anyhow. Heck, my Rhonda, she put the starch in my shorts mighty quick. And I was a wild shit. Worse than these goomers in the rust buckets with the dirty bumper stickers on the back.”

“As I said before, Ma didn’t mention anything about you to me.”

The more reserved she acted, the more Bib seemed to enjoy himself. “If you don’t beat all. Seriously, kiddo, you I should think about takin’ a page from your mom’s book and leave if you don’t want that clerk job. With your education, you’re only hurting yourself by staying, and you know it. Ewerton’s not a town for someone like you. Heck, you don’t talk like the rest of us do, let alone act like us. For most people, Ewerton’s good, but not for you. Too much baggage, y’know what I mean? And it ain’t fair, since it didn’t have nothing to do with anything you or your mom done.”

His omission of the old lady’s name wasn’t lost on Anna. Unbidden, the memory of the neighbors telling Ma about the old lady doing dirt on their lawns returned. It was just plain craziness. Anna had read about the exact same behavior in Sybil during her psychology class in college. Her professor, a laconic fellow who always wore jeans and baggy turtleneck sweaters to class, had claimed that the real Sybil had lived somewhere near Wisconsin, or in it, and said that there were clues to her hometown in the book—but Anna had never been able to find them—as if she’d actually wanted to know where another family in pain once dwelled.

Maybe it’s a Wisconsin thing—nutty middle-aged ladies like Sybil’s mom and my grandmother dropping a load in their neighbors’ shrubs. Body language to the tenth power or something.

“There isn’t actually nothing holding you here.”

“Listen, do you think our leaving would have made it not happen? People can find out what they want about you, or your kin. I know—my father did it with Ma. Hiding never works—not if it means hiding from yourself, or your blood. Running away would only mean that what my great-grandfather did does matter.”

Unable to go on, yet unable to leave, Anna stood there next to the car, struggling to catch her breath, feeling the familiar, unpleasant tightness there, and blinking back wetness in her eyes.

Bib paused to blow his nose, then, as he pushed his hankie back into his pants pocket, said, “Yeah, well...you just take that slip of paper to Marv, and tell him I recommended you for the job, And don’t worry none about paying for any training. CEP takes care of that. Really, it’d pay a lot more than what you’re doing now, and the hours are better.

“Y’know, I’m not tryin’ to give you a hard time here. You understand that, Anna? It’s just that I’m aware of certain things that’ve been going on, and sometimes a person can do something about ’em, and sometimes not. This is one thing I can do, okay? It don’t make up for what’s been, but maybe...well, you just take that slip in to Marv. Now you better get home, before whatever got that Hibbing witch gets you.”

Recovered now, Anna said with a tight smile, “Animals...know better than to mess with me. I bite.”

“That you do, girlie, that you do.” Bib smiled as he turned on the ignition and began to back away from the rear of the grocery store, Anna took off, mesh bag banging against her thigh, without so much as a good-bye or thank you. She still wasn’t sure if she should go see Marv Krumb down at the Concentrated Employment Program office, but as long as she had that note written in the chief’s hand....

It wasn’t until she was almost home, completely out of breath, as usual, that Anna realized she hadn’t once heard or seen old Mrs. Campbell that morning, and figured, Old bat’s probably afraid she’ll be the next one to get a frigging heart attack in the woods.

TWO—The Old Lady (1)

“—and when I heard the news on WERT, I said to myself, ‘That was the bitch who fired my Anna’.”

Anna toyed with the piece of tasteless, boxed pumpkin pie the old lady had cut for her, mashing the crust crumbs into a flat little cake off to the left side of the china plate. Ma had told her how bad the old lady had become in the years since she and Anna had left, but even with the proof of the old lady’s deteriorating voice over the phone, Ma’s powers of description had been sorely limited.

It didn’t help that Anna knew exactly when the old lady had really been born. When it came to the old lady, sixty-two going on sixty-three come late December was an abstract term, as meaningless a measure of age as saying the universe was older than time, or that hell is forever.

Anna’s grandmother was an old, old lady, of seemingly advanced physical age. Oiled parchment and wrinkled tissue old, with dots, splotches, stiff short whiskers and age warts liberally covering her sagging skin. Her cheeks hung like empty purses beneath her high Czech cheekbones. Lank, almost indifferent strands of gray-white hair sparsely covered her domed, slightly shining whitish scalp. Her nose had ballooned with the years, to match basset-lobed ears, and she had a turkey wattle under her weak chin. Her lips were obscene, thickly protruding and shiny purple-wet, like the skin of a blood-engorged vagina. And her slightly nearsighted eyes resembled those of a doll that had been left outside too long in the sun and mud and snow, an abandoned plaything whose time spent in the open had leached the color from its irises, until only the pupils remained, a dark, hypnotic pair of disembodied dots in a sallow sea of red-veined off-white.

But the old lady’s hands had to be the worst part, Anna decided as she reluctantly swallowed the cold pie.They were puff-knuckled, twisted, with nails the color of margarine gone bad in the wrapper, lined with something faintly transparent yet dark, like ancient scalp oils or raked-up dead skin—yet oily, with dark dappled blotches across the metatarsals, like the underbellies of some spotted hunting dogs.

And if the way the old lady looked wasn’t awful enough, she smelled, a rancid, slightly fulsome odor not unlike wet mold or slimy, ripe, worm-pocked meat. The old lady had emitted that stench long before her formerly thin lips sprung, or her skin went slippery-crepey. Anna remembered how Ma refused to wash any of the old lady’s things along with the old women’s garments. If Ma threw in as little as one pair of the old woman’s socks or panties, the whole wash smelled gamy, like an ill-dressed deer carcass hanging in the sun.

The fights they’d had over the wash had helped bring things to a head the summer before she and Ma left the house, even though Ma had offered to do a special load of the old lady’s things. But the possibility of not being part of the “family” had freaked the old lady out, made her rage, teeth bared, and throw things, like a caged monkey in the zoo, shouting, “I already lost my other family; now I’m losing it again!” And not long after that, Anna had vowed that she would never look the old lady in the eye again until the latter’s eyes were closed for good. Yet here she was, heart aching because being here, in the house where she’d grown up, which contained such mixed memories, reminded her of just how little she had at the house she and Ma had shared on Wilkerson Avenue. And she’d flinched inside when the old lady had opened the door, staring dumbly at Anna before sputtering without preamble, “My little Anna’s hair was blonde—you’ve got dark hair,” before letting her into the house, blithely ignoring Anna’s protest, “But I’m almost thirty now. As I’ve grown older, my hair darkened.” And her reunion with the old lady had deteriorated from there, until Anna found herself sitting at the old-fashioned five-legged white enamel kitchen table, eating a miserable wedge of pie she didn’t want, listening to the old lady rehash yet another of Anna’s past job failures. Thanks a lot, Ma.

Anna had worked for Norm Hibbing all of three days before his skunk of a wife Inez had fired her, for “gypping me.” What had actually happened was that Anna had been framed. Inez hadn’t been able to stand it when Norm spent coffee breaktime talking to Anna about books and writers. They discovered they shared the same alma mater and had both studied English literature under the same professor. On Anna’s last day, of employment, Inez had made a phone call to a friend of hers—a blue-eyed Indian woman named Sharon.

As soon as Norm left the store later on, Sharon showed up, a ten-dollar bill in hand, asking for change, singles; Inez was too “busy” unloading a shipment of dirty pens (click the top and the man’s shorts fall off), so she let Anna handle the transaction. And then, as soon as Norm came back from the post office, Sharon returned to the store, saying that a mistake had been made—she’d only handed over a five-dollar bill, not a ten, and that Anna had given out too much change.

Inez—ugly, ignorant little Inez, with her miniskirts, pinched iodine features, and filthy, filthy fingernails—had squeaked, “I don’t want no college-educated dummy” manning her till, and same alma mater or not, Norm was forced to give Anna the boot.

Anna had been so ashamed of the incident that she never mentioned it to anyone except Ma, nor did she list the novelty shop on her later résumés, even though it was most likely a violation of some law or another. She already had so much going against her....

“Yes, that was the bitch. Nobody in town seems to be broken up about it,” Anna remarked, forcing down another bite of the pie, nearly gagging on the mealy crust.

“They shouldn’t be,” the old lady pontificated, cutting herself a second slab of pie. For a woman only five feet tall, and not exceptionally fat, the old lady packed in a prodigious amount of food.

“Because when I heard it on the radio, I told myself, ‘Mark my words, that bitch is getting hers for all the bad she did.’ Like my Gramma always said, ‘The evil get theirs.’ She had trouble with the scum-bums, too.”

“Yahoos,” Anna remarked absentmindedly, as she forked off another piece of gelatinous orange but didn’t eat it right away.

“I beg your pardon?” The old lady was in her coquettish mode again—Ms. Imperious. It was her only standby when she hadn’t the foggiest what someone was talking about.

“Yahoos...from Gulliver’s Travels. Book Four—the part about the country of educated horses.”

“I only remember the little people who tied him up.”

“Those were the Lilliputians. Gulliver met up with them on his first voyage. We only studied the fourth voyage in World Lit. Anyhow, Gulliver is washed up in this country where the intelligent beings are horses.”

“I saw a horse once, on the TV, that could count with its hooves.”

Anna nodded, trying to ward off a complete recitation of the show her grandmother had seen. She had already heard what was on People’s Court the afternoon before, down to every word Judge Wapner uttered.

“Well, the horses were like people, while the people—or what Gulliver eventually discovered were the people—were called Yahoos, They were very hairy and dirty.”

“Like those scum-bums who drive up and down the street at night, honking to beat the band?”

Anna was pleasantly taken aback to hear the old lady echo her own thoughts. “Scum-bums” was an apt expression,especially for people like Zack Downing and his brother-in-law Elmo Effertz (the Effertzes—a farm family from out past County Trunk QV to the south—had a penchant for weird names. Zack’s zit-faced wife’s name was Irma), who spent half the night gunning their engines, shouting obscenities, and slamming their car doors while she tried to sleep,

A couple of years back, Zack and Irma moved into the very small frame house next to the Sudek house. The couple used to wait until well after sunset to begin work on the tiny addition they were building onto their house, Not that they weren’t home from their respective jobs at the Red Owl and Ewerton bakery (he cut meat, she arranged bakery on plastic trays) hefore sunset—they only worked part-time, and got home by three at the latest. They simply seemed to like making noise at ungodly hours. And to pile on the insult, they’d taken out their old bathtub and just left it sitting there, next to the rough-looking little barn-shaped prefab shed Zack had slapped up a few weeks before.

And when one of the Sudeks’ other neighbors had complained about the tub to their city councilman, Irma of the creamed-corn complexion and whiny voice had called everyone on the block, accusing them of making the “mean call about our tub,” Irma’s vocabulary level matched that of a small, whining child. When her cat was lost (again), she called it “my kitty cat,” and when her husband’s hunting hound was barking, it was “Zack’s doggie talking loud again.”

More than once Anna wondered who’d bribed the examiner when Mrs. Downing took her driver’s test (like Norma Grasnowski bribed the fellow when her retarded son Gary took his test—and passed). She doubted that the examiner was as hard up as potbellied Zack was when it came to getting a freebie in exchange for a passing test.

To Anna, creatures like Zack and Irma and her missing link brother Elmo of the perpetual stocking cap and half-unbuttoned plaid shirts were hardly worth the air they inhaled or the food they ingested. It was as if a command from God had gone wrong, and instead of being the goats or swine or worms they deserved to be, they had scaled the evolutionary ladder a little too soon. Rather like Jonathan Swift’s Yahoos, who looked and even on occasion acted like people, yet were still animals who ate raw ass flesh and smelled each other’s asses, unashamedly.

She was never sure if her own family situation made her feel so unaccountably above those with less gray matter upstairs, and much less couth in general. If the way she had been treated produced her feelings of superiority, so be it, she figured. Perhaps it was the way the ones who tormented her got theirs back. At any rate, regardless of why she dubbed them Yahoos, they did act as if they belonged to a sub-species of the human race.

I mean, how can cruds who put bumper stickers on theircars saying, “No muffs too tough—we dive at five,” or “Wanna get laid? Crawl up a chicken’s ass and wait” and leave skinned-out deer carcasses in the driveways after bow-hunting season, expect to be treated like decent human beings? You act like an animal, prepare to be regarded like one....

“...and my Gramma always said, ‘Just because it walks upright and wears pants doesn’t mean it has to be called a man—’”

Anna put down her fork and stared at the smelly old lady. Doubt filtered into her mind. Had the old lady really been so terrible during all those years, or had some of the badness been in Anna’s mind? The old lady was actually making sense for a change, while Anna’s memories suddenly seemed surreal, childish in their simplistic black-and-whiteness.

The dichotomy of her feelings was growing too uncomfortable; she had to either change the subject or leave the house. Pushing her plate forward with a forced burp, she said, “No more. It’s wonderful, but I’m so full.”

Leaning against the back of the white wood kitchen chair, which had been part of the old lady’s mother’s kitchen set, before Anna’s great-grandmother died not twenty feet from this very room, if the old lady’s account of the incident could be believed (and if what Bib Stanley inferred that morning was correct, a lot of people didn’t believe what the old lady had to say about the night her father went...strange)—Anna glanced around at the kitchen, and the rooms visible beyond. Even though Ma had been coming over to clean up for the past few years, the place was still a rat trap, the walls oddly mildewed, with moldy black circles indicating the studs underneath the painted plaster walls, and a funny, sharply stale yet damp odor permeating the sticky varnished woodwork.

Old newspapers, magazines, and Dean County Shoppers were stacked in piles everywhere. Anna doubted that the bundles of paper the old lady kept were worth anything; the old lady had Ma religiously deposit her social security checks in the Ewerton Savings and Loan (the old lady had worked only a few years, back in the early fifties when they were strapped for workers at the paper mill), along with her trust fund checks from the combined money her maiden aunts had left her years ago.

Odd, when Anna got to thinking about it, that the two old women (Anna vaguely remembered Aunt Joan, who was all talc and spider-down hair when Anna was tiny) didn’t trust their grown niece with a lump-sum inheritance, as if she was still the six-year-old half-orphan entrusted to their reluctant care.The trust fund did work out for the best, though, since it was in interest-bearing bonds. And considering that the old lady had had no husband to count on for a bigger cut of social security, the trust fund kept both the old lady and the family house in one piece.

Not that the house seemed to be of a whole; ever since Anna could remember, parts of it had been inaccessible, off-limits.The old sewing room off the kitchen, for obvious reasons. The basement, at least for little Anna. Ditto for the attic, which was said to have bats fluttering loose in it. A couple of the bedrooms were shut off, empty and airless, because they weren’t needed.

And now, without Anna and Ma constantly around to keep things reasonably clean, the place was going to seed within. Flat bats of dust settled under the bigger pieces of furniture; hazy films of it covered the flat surfaces (Anna remembered how the old lady used to tell her, “I don’t have to dust...that’s your job”—and Anna was all of four years old, barely big enough to grasp the wooden handle of the feather duster), and the jumble of bric-a-brac assembled haphazardly on the end tables and hanging shelves. One shelf was a geometric black affair backed with several oversized gold-painted wooden leaves. The leaves had gone springlike, all green and soft looking.

The musty tang of mold spores made the inside of Anna’s nose sting. Ma had said that when she first came back, the old lady’s coffee grounds were piled up in a gray bearded heap on the counter, and that her linens were indescribable. There were torn shreds of towels and washcloths, mended and remended, sitting out, while dusty, fluffy stacks of new, unused towels, part of Ma’s bridal gifts (the same towels which the old lady had removed from their packing boxes before they moved out, and replaced with old stained floor rags and dishrags), rested on the high shelves near the bathtub.

And the old lady’s toilet still wasn’t working. If you wanted to flush, you had to dump in a bucket of water. Anna wondered if the plumbing remained unrepaired by design or accident. It was common knowledge that no repairman would set foot on the Miner house porch unless Ma was there to keep the old lady away from the fellow while he worked.

(Once, a couple of years before Anna and Ma left, during one of Anna’s winter breaks from college, they had had the back screen door replaced, and the old lady leeched onto poor Steve Umbert and refused to back off. She made him hot chocolate after he expressly told her he didn’t want any, then fumed when he took one sip of it and left the remainder untouched. And worst of all, she’d dragged Anna downstairs, hiss-whispering, “Go on, flirt with him!” and Anna shook off the old woman’s grasping claw, with a horrified whisper, “How could you? The man is married. I know his wife. You are absolutely disgusting—just because you fooled around doesn’t mean—”

(If Steve hadn’t been there, Anna might not have screamed so much when the old lady hit her, but Anna had to let someone know what was going on—and when Steve came running, wanting to know what was happening, the old lady made it seem as if Anna was doing something to her, pulling away, whining, “Don’t hit an old lady...I’m just an old woman! But Steve’s eyes were knowing as he quickly wrote out a bill and said, “I’ll have my brother come over later to finish up,” only his brother Chad never did come, of course, and Ma ended up doing the job herself...and for some odd reason known only to themselves, neither Anna nor the old lady explained why Steve left in mid-job....)

Yet those incidents seemed so alien, so removed from reality. that Anna found their very veracity questionable, even though there were plenty of people in town who could have either refreshed or supplemented her memory of them, if only they’d realized that she was now doubting. And paddling happily in dangerous depths.

“Yahoos...I do believe that I like that word,” the old lady was saying. She added, with a phlegmy gurgle, “It’s...how do you say. Asp.”

“Apt,” Anna gently corrected, pulling the plate of pie back for one last polite bite.

“Yes, apt. Like my Gramma used to say, ‘If it walks upright and wears—’”

“Oh, guess what,” Anna quickly interjected, before the old lady did a complete rerun of their conversation, “I met Bib Stanley this morning, and he said there was a job opening at the station. Clerking, and being a matron.”

Panic shone in those colorless eyes. “You can’t be a matron, you’re not—”

“Anyway, I have to stop at the CEP office and ask about it,” Anna butted in, not wanting to hear another of her grandmother’s word games. “And I don’t know if Marv is going to be there later on this afternoon—I think he takes off earlier than the rest of the workers—so I’d really better get going. The pie was great. I’ll be back later on this week, okay? And. call if you need anything before then.”

“When you get home, be sure and give me the signal. I worry about you, walking and all.” Anna had wondered when the old lady would be getting around to that same schtick she pulled on Ma. The minute Ma got home from the old lady’s, she had to go through the same old triple-blind phone routine, just to check in.

“Control,” Ma would say. “She wants that same old control. Worried, my ass. If she can’t get it one way, she gets it another. Control,” as her face got red in angry, strawberry-shaped blotches.

Anna nodded, and said, “I’ll be sure to do that, although I’ve been walking like this for years, and early in the morning, too.”

“You shouldn’t have to do that,” the old lady demurred, but Anna caught her drift—you shouldn’t do that, period. As if she didn’t want her granddaughter out doing things she couldn’t control or supervise.

“It keeps food in the fridge.” Anna shrugged as she looped her purse strap over her right arm.

“Once you get that job, you won’t have to go out early, will you?” That same six-year-old’s wheedle that used to drive Ma crazy, and no doubt drove Aunt Joan and Aunt Bella insane—in the latter’s case, for real—when the old lady was a little girl. What was it that the old lady’s father was supposed to have said before they carted him off?

“Take care of my Lucy,” or “Watch over my Lucy.” Something no doubt suitably romanticized by the old lady over the years, to show how much her father adored and loved her, and to underscore how mean and nasty her late mother’s sisters were to poor little Lucy Miner. In reality, her father had probably been yelling, “I’m innocent,” or something better suited to the occasion at hand—said hand that happened to be carrying a dripping, reddened ax....

“If I get the job. I’m not counting on it. You find that out in this town. It’s all who you know or who you’re fucking.”

“Oh, Anna.”

“I’m almost thirty years old. I’ve earned the right to say fuck once in a while. Really, though, I have to go. See you later, okay?” Anna said as she let herself out the door and quickly shut it behind her, just as her mother used to do. The old lady claimed that getting up and down too much wasn’t good for her, yet, despite her claims of dizziness, she wouldn’t let either Anna or her mother have a key to the front door, which made Anna come to the conclusion that the old lady’s claims of dizziness were just that. Claims.

But she didn’t consider any other alternatives for the old lady’s persistent habit of making her wait for up to four or five minutes while she slowly made her way to the door—alternatives that had nothing—and at the same time, everything—to do with the state of being dizzy.

And as she walked up Evans Street, toward the CEP office at Fourth Avenue East, Anna didn’t think to turn around, to see if old lady was watching her through one of the white frame house’s many windows. Ma had said the old lady was in the habit of doing so, another example of control. But if Anna had looked backwards, just a peek, she might have stopped cold—although her grandmother was watching her, she wasn’t watching through any window she could have reached in the short time it took Anna to walk from the porch to the sidewalk.