Читать книгу People of the Mesa: A Novel of Native America - Ardath Mayhar - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Eleven

The mesa had not changed. The people and the dogs, the birds and beasts and plants seemed to be just as they had been all Uhtatse’s life. From his earliest memory, little had altered on the high mesas.

Yet something had changed. He had changed, permanently and drastically. The mantle of responsibility that had hung about his shoulders as he stood on the quivering rock of the promontory might have been laid away in its basket, but the reality of the task it had bestowed upon him was never absent from his mind.

He slept little. It was summer, and that was the time when the enemy would come, if the Kiyate came at all. The most worrying thing about those fierce people was their randomness. Years might pass without an incursion, and still they might hit the vulnerable pueblos at any time. He had to be watchful, day and night.

It would have helped to have the comfort of his own home and Ihyannah, but their true marriage would only take place when they moved into the part of the pueblo that would be Ihyannah’s. Until then, they could take pleasure in one another, talk and laugh when there was time, and walk away into the junipers to make love. But they could not live in the same house or eat from the same pot. They could not reach out in the night to comfort each other’s nightmares.

Those nightmares, for Uhtatse, were becoming regular visitors. He would wake, sweating, on his bed-pile. Not until he rose and went out into the night, walking fast and breathing deeply, would he shake away the miasma of the dream. And yet he could seldom recall the substance of that dream—what was it that was haunting him in the night?

When he began to awaken others in his mother’s house, he took to sleeping outside amid the piñons clumped together beyond the pueblo. It was chilly, once the sun set, but he rolled into his feather blanket and tried to sleep. The dreams became worse, not better.

The restlessness of his dreaming sent him moving about the mesa at all hours. Even in the darkest time of the night, he would roam up and down the slotted rims of the mesas, feeling afar for any disturbance. He believed, more and more, that there was danger out there in the lower country, moving nearer and nearer as day followed day.

It would have helped if he could have wearied himself with hard work in the gardens or with the hunters. Yet now he was committed, and it was impossible for him to distract himself with those necessary labors. Others must do those things, while he sent his senses frantically across the mesas and over the lands below.

He said nothing to Ihyannah. Her laughter was precious to him, and he would do nothing to damp her high spirits. Indeed, only her cheerful heart and her warm, responsive body made life bearable for him, as the summer bloomed and faded.

His wife, however, was sensitive as well as intelligent. He lost weight and became abstracted. That was not lost on her, and she came at last to touch his shoulder.

“You are troubled, Uhtatse. All is well on the mesa. There is no sickness. The gardens flourish. The game is fat and the weather excellent. The thing that troubles you comes from inside, not from outside. It will make you ill, if you keep wandering in the night and worrying about whatever is down there in the low country.

“It would help if we could live in the same house, and yet the building of the new space is not complete. It is forbidden to move into rooms that have not been purified and had the ceremonies performed to make them wholesome. If you will allow me, I will move out into the piñons with you.”

He turned to lay his cheek against the top of her sleek head. She smelled like earth and air and juniper. That comforted him on some deep level of his being.

“I feel as if the weight of the mesa rests on my shoulders,” he said. “I worry that some enemy will creep up, and I will not know. I am responsible for the safety of our people, and I feel that I am not old enough—or skilled enough—to keep them safe.” He sighed. “Ki-shi-o-te tells me that this is natural. No one, however skilled, he says, can keep anyone safe, for our world is not a safe place. And yet I cannot rest, and I dream....”

“We will build our own house,” said Ihyannah, aware that she was saying something unheard of.

Uhtatse drew away to look down at her, his eyes wide. “It is forbidden to build on the mesa, except in the prescribed ways. And a pit house would take more time to dig than I can spare from my work, besides being cramped and stuffy.” He tightened his arms about her, staring away across the canyon.

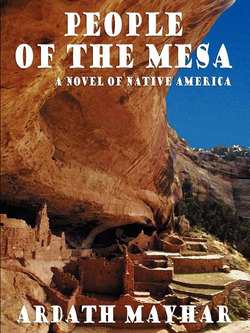

He found his gaze lingering on the deep arch that opened into the side of the cliff beyond the gulf of space. A cave. He had explored it when he was small. It was deep and cool, with a spring seeping from the stone in its deepest part. There were others like it along all the cliffs on both sides of the canyon.

He had a sudden recollection of the words of the Anensi trader. Those tales of cliffs that the people of the south built for themselves and within which they lived.

A house built into the cliff cavern would be cool in summer and warm in winter, shielded from the blasting winds that swept the high places. It would be safe, also, from enemies, who would have to negotiate the almost impossible climb down to it.

“The cliff,” he breathed. “We could build a house inside the cliff. That would break no rule.”

Ihyannah pulled free to stare into his face. “In the cliff? How?”

“Look over there, at that small cave. There are others below us, here, large ones and small. Most of them have little springs seeping from the stone, too. We could build a house there, and it would not be on the mesa. The ritual would not have to be performed for an entire House. We could live there until our part of the pueblo is finished.”

For the first time in weeks, he looked animated. There was a coppery glow beneath his dark skin. His eyes were bright, instead of harried.

Ihyannah turned to lie on her belly and stare down the cliff side. “There is a cave just below us. I used to play there when I was small. It does have a spring—yet it is a long way down. It is not easy to get there, though I thought little of it when I was a child.”

Uhtatse sank back into her arms, his cheek again against her hair. “It would be a very difficult thing. Dangerous, too. We would have to do it all ourselves, for there is no one else who can spare the time or take the risks.” He frowned. “And I must watch the mesa. How can that be managed?”

She laughed, shaking in his arms. “We will go on a long scout. Down past the Middle Way to the very bottom of the mesa. We will move across those distant lands below, and you can sense everything that moves. If it takes days, then we will take those days. When we return, you will know that there is no trace of the Kiyate anywhere within range of us.

“Then we will begin to build my house. If we work for half the day and you range the mesa for the other half of every day, then all will be done. Nothing will be neglected.”

Uhtatse felt his spirits rise. For the first time since he had held his position, he felt some ease of mind. The dark mouth of the cave smiled at him. A magpie above his head shrilled an inquiring note, and he looked up to smile at the bird.

Something was trying to speak to him. Something inside struggled to make itself heard. If he was patient, he would know, eventually, what it was.