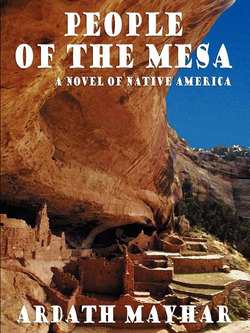

Читать книгу People of the Mesa: A Novel of Native America - Ardath Mayhar - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Six

The wind was sharp, even by day, and as the evening drew in and the sun moved below the farther edge of the high place, a chill breeze whipped through the canyons and about the spot where Uhtatse stood. His bare skin flinched into goose pimples, but he would not allow himself to shiver. He kept his arms in place, his legs steady under him, his teeth clenched tightly to stop their chattering.

His thoughts seemed to float away, high above his patient flesh. The cold was a thing he would not let into his consciousness. The hunger that soon growled in his belly was likewise rejected. The pain of standing on the sharp slivers of stone was so minor that it took no act of will to foreclose it from his mind.

Night hid the cliff across the gorge. Only its deeper blackness loomed against the stars, as bats moved above the cliffs and down into the canyons. He could hear the shrill screeches, though few of his kind seemed able to detect those almost inaudible cries.

The long cry of a hunting cat came to his ears, from down in the Middle Way where the deer browsed. An owl quartered the cliff top skies above him. He could sense the downy beat of its wings. Somehow, in the darkness it was easier to sense all the hundreds of living creatures that shared the mesa with his own kind.

He concentrated fiercely, feeling for any whisper of the air among leaves and needles. He felt for the dim sensing of the yucca and even more humble plants. To know the living things, one must also know those that did not move or truly think. Yet their reactions could reveal many messages to one who could sense them.

It did not come in one night, nor yet in two, that ability he needed and sought. Uhtatse stood in the niche, his skin weathering like old wood, his mind soaring and searching among all the things living on the mesa and along its sides and in its streams.

As his belly flattened against his backbone, and his ribs began to stand out like the ribs of the baskets his grandmother wove so well, his mind grew fat with another kind of food. Even had he been able to hear the words of plants and beasts unerringly, from the beginning, he knew that he would have been greatly improved by the things his stay on the cliff side was teaching him.

He forgot to count the days and the nights, as his spirit drew farther and farther away from his body. Such matters ceased to have any meaning, and he began feeling as if he might be a part of the wind moving about him, the light or the darkness wrapping around his body. A day came when he knew something of the stone against which he stood. It was a long patient tale of sun and wind and weather leading back to a time when water, wonder of wonders, lapped at it, and it was gritty stuff not yet hardened into the pale golden sandstone that he knew.

Realizing that he had heard the stone, he awoke from the trance that had held him for so long. He listened hard, and piñons whispered to junipers, which hissed back at them news of birds perching on their branches, sun warming their needles. He heard in his mind the small shriek of oak leaves being nipped away from their tree by the deer in the Middle Way.

Then he pulled himself back into his flesh. That was no easy thing, for a spirit that has known the freedom of the air does not willingly return to the burden of bone and muscle and nerve. As his mother twisted yucca fiber on a spindle, drawing into it bits of fur or feather, he spun himself back into his body. When he moved, at last, pain shot through every part of him.

He shook himself, squeezing his eyes shut. Then he opened them wide. Sparks of red and blue and white danced before his gaze, until his eyes cleared and morning light shone steadily.

To move his hands and arms was very slow and terribly difficult. He took his time, flexing himself bit by bit, part by unwilling part. Now he felt that his body had grown light and brittle-seeming. He felt as if he might step out of the niche and float, like a dead leaf, lightly down into the canyon. But that, he knew, was caused by the long lack of food and water.

He did not trust himself to climb back to the cliff top until he was sure he could rely upon hands and fingers, feet and toes to do their work dependably. Even then, he moved slowly, taking great care with each hand and foothold. As he climbed, he felt the world winging through him in a thousand unfamiliar ways.

The wind spoke, as did the gritty stone beneath his fingers. When he reached the top and stood, facing back out over the dizzy deep, he shouted aloud the triumph of his spirit.

“HO!” he cried, hearing the echo go bounding away along the canyons. He wanted to say more, to cry out to the morning his discovery of all this new world he was finding with every breath he drew. But he could find no words worthy to offer to those gods who had made him this gift. So he cried again, “HO!” and heard the echoes wear themselves away among the stones.

And when he walked beside the corn plantings, he could hear the growing of the strong shoots in the sunlight. As plainly as those of his kind who worked among them, they spoke of well-being, of pain at being bruised or joy at feeling water from the catch-basins cooling their roots.

He must have been smiling broadly, for all who met him on the way began smiling in return, when they saw his face. Ki-shi-o-te came from his house to greet Uhtatse, and Ahyallah forgot herself and sprang up from her stool beside her pile of yucca fibers to lay her hands on his shoulders. She had not done that since he was a boy.

Best of all—more than best, indeed!—was the reaction of Ihyannah, Ki-shi-o-te’s daughter. She smiled as they passed on the trail.

That was better than food, better than being rubbed with oil and given clean clothing and his new blanket to sleep under. Indeed, once he stretched himself upon the hides of his sleeping place, that was the thing he dreamed of for hours and hours, as the sun sank and rose again outside the pueblo.