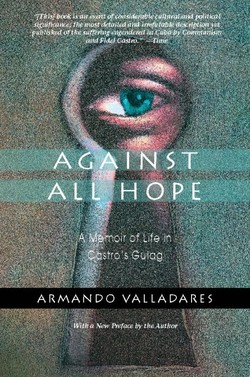

Читать книгу Against All Hope - Armando Valladares - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

LA CABAÑA

The fortress of La Cabana was built by the Spaniards two hundred years ago to protect the entrance to the port of Havana. When the English took the port in 1762, the first thing they did was secure this fortress. Because of its location, it was said, “Whoever holds La Cabaña holds the key to the city.” Since the triumph of the Revolution, it had been converted into a political prison, and in its deep moats, now dry if they had ever been filled with water, the executions by firing squad were carried out.

La Cabaña sat atop a hill on the opposite side of the bay from Havana. It was very isolated. Great parade grounds, firing ranges, and open land surrounded it. The artillery school was located there.

They opened a small metal door and ordered me inside. Now at the entrance to the fortress, I could see the prison yard in front of the galeras, large rooms which had served the many purposes of a colonial fortress-barracks, storerooms, ammunition magazines, and so on — and which now were barred and used as large cells for the prisoners held there. There were hundreds of prisoners looking out curiously at us, the new arrivals. I went first into a small apartment, where they registered me and gave me a card, and then to the storehouse. There, they stripped off the clothing I wore, a new suit, and gave me the prison uniform, which had a large black P stenciled on the back. They promised to give the suit to my family the first time they came to visit me, but they never did. The head of the storeroom had been a member of Castro’s guerrillas; he was now in prison for the crime of armed robbery. These “delinquents,” common criminals, lived in a galera which opened off the main gate outside the central patio, intentionally kept separate from the political prisoners. They still wore the olive-green uniform, and this one wore his hair in a ponytail in imitation of Raúl Castro. He hated political prisoners, and never missed an opportunity to show it.

I left the storeroom and found myself suddenly in the prison yard, in the midst of that multitude of prisoners. I didn’t know a soul. They had assigned me to galera 12, so I went to look for it.

At the door, a young prisoner stood watching me. Behind his sunglasses, his bright eyes sparkled with intelligence and bottled-up energy. He smiled affably and extended his hand. He was Pedro Luis Boitel, a leader of the Student Movement at the University. He had fought against Batista in the underground and later had managed to flee to Venezuela, but he had returned when the dictator fell. He had recognized me from the photographs that had appeared in the newspapers. He was the first person I met there, and we became great friends, as close as brothers. Boitel lived toward the center of the gallery, on a high bunk. All the beds were taken. There were too many prisoners.

The galeras were vaulted galleries — that is, shaped like rural mailboxes, or tunnels, open at both ends. One end of all of them faced the moat that circumscribed the fortress. At that outward-facing end of the galeras, they were secured by not one but two iron gratings of thick bars. The walls were about three feet thick, so the gratings, which were on the exterior and interior faces of the walls, wound up spaced about a yard apart. There were two masonry observation posts, called garitas, at the top of the wall around the prison yard from which guards with machine guns always kept the prison yard, the prisoners, and the iron bars of the cells under surveillance.

That afternoon some of the prisoners who had been with me at Political Police Headquarters arrived — Carlos Alberto Montaner, Alfredo Carrión, Nestor Piñango, and some others. They all knew Boitel from the University, and they were also sent to our gallery.

The first night we had to sleep on the floor between the beds and in the passages between the rows. Since one end of all the cells opened to the north, the cold wind blew fiercely through the barred window arches. There were not enough blankets to go around, and we almost froze. The next day we got word out to our families that they would be permitted to visit us.

Two men, cousins, Ulises and Julio Antonio Yebra, had been arrested the same morning I had. They had appeared in the newspaper photographs too. Julio Antonio was a doctor, and a brave man, brave almost to the point of rashness, in fact. In the search of his house, they had discovered an old .22 rifle. That was all. The Political Police deduced that if he possessed a rifle, it must be that he intended to use it against someone, and since Julio Antonio was well connected in the Revolutionary Government, since he was a professional, he couldn’t intend to use it against some rank-and-file soldier, some simple unknown militiaman. The someone had to be someone important, a leader of the Revolution, and who more important than Fidel Castro? That was the reasoning which led to Julio Antonio’s being accused of possessing a weapon intended for use in an attempt on Fidel Castro’s life. He was sentenced to death.

During the Batista years, Armando Hart, one of the leaders of the 26th of July Movement and current minister of culture in Cuba, had been jailed. So had his wife, Haydée Santamaría, at that time the third-highest-ranking woman in the regime, director of Casa de las Américas. (Years later, on a now-symbolic 26th of July 1982, disillusioned by the system that she had helped to implement, Haydée committed suicide.) Julio Antonio had pulled off a courageous and daring coup by helping to rescue Armando Hart from the hands of Batista’s police when Armando was being tried in the Audiencia building in Havana. Now the situations were reversed Julio Antonio was the one in prison. So Julio Antonio’s mother knocked on Armando Hart’s and Haydée Santamaría’s door. It was a time for loyalty, a time to acknowledge the debts of friendship, but they flatly refused to intercede for the man who had saved their lives. Worse even than that, Haydée wrote a letter alleging that Julio Antonio had participated in anti-Castro demonstrations. The letter went on to say that he had never really been a completely trustworthy person.

Julio Antonio was tried under Article No. 5 of 1961. This law took effect five days after his arrest; they applied the law to him retroactively. His trial began early in the morning. At noon the next day, a two-hour recess was called. Julio returned to his cell and said to one of the men there, “Do me a favor — open that can of pears you’ve been saving and give me a glass of milk. That’s the last thing I’ll ever eat, since tonight I’ll be far away from here, close to God.”

Many of the men tried to reassure him with words of sympathy and comfort, but he merely repeated gently and calmly, “Yes, tonight I’ll be with God.”

He wrote several letters. At two o’clock that afternoon, they took him back to the trial. Julio Antonio didn’t return to the cell this time after he left the trial. He was left in one of the small chapels in the fortress, which were now reserved for prisoners sentenced to death. Men who were there say that he behaved with the same strength and valor during the trial that he had always lived by.

At nine o’clock, we were in the habit of gathering into groups and praying in all the galeras — faith in difficult times. The sound of a motor was heard. Total silence fell. It was the truck carrying the coffin for the corpse. Then we heard the motor of a jeep that was carrying the prisoner, and some voices. There was a long stairway leading down into the moat. A few yards from the wall stood the wooden stake to which the prisoner was tied. Before they tied him up, Julio Antonio shook hands with each one of the soldiers on the firing squad and told them that he forgave them.

“Firing squad ... attention!”

“Ready! ... Aim! ... Fire!”

The discharge was ragged; the platoon fired in disorder, not at all in unison.

“Down with Commun — !” Julio Antonio’s cry was never finished.

Then there came the dry crack of the coup de grâce behind the ear. I will never forget that single mortal sound.

Within the prison, the silence was dense and charged with suspense, until it was broken by the sound of the hammers nailing the lid on the rough pine box. From our galera there was nothing to be seen, but we could hear everything. I imagined the scene: the prisoner tied to the stake, the marksmen, then the fall of the dying body, its breast ripped by the bullets. “May God receive him in His arms,” someone cried, and Ulises, unable to contain himself any longer, began to cry for his cousin.

The next day, Pedro Luis Villanueva and some other prisoners declared a hunger strike to protest the shootings. They were taken out of the yard and carried to the chapels. Clodomiro Miranda, former commander of Fidel Castro’s army, was also being held in that improvised death row. Clodomiro had joined the rebels in the mountains of the province of Pinar del Río, the most westerly province of Cuba. He had fought with great courage defending liberty and finally rose to the rank of commander.2 Though he was not a man of great political consciousness, he could see clearly enough that the Revolution was not taking the course that Fidel had promised for it. So when he realized that the ideals of the Revolution had been betrayed, Clodomiro Miranda took up his weapon again and went off once more into the mountains. Castro ordered him hunted down, and thousands of militia were sent out to find him. He was wounded in a skirmish. When they captured him later, his legs had been completely destroyed by bullets, and there were other shells lodged in one arm and one side of his chest. He was carried into his trial on a stretcher. When they sentenced him to death, he was taken out of the military hospital and locked up in one of those horrific cells without a bed. Clodomiro was unable to stand up, so he had to drag himself along the filthy floor. His unattended wounds became infected; then they filled with maggots. That is how Pedro Luis and Manuel Villanueva found him. They were the last prisoners to speak with him.

It was also on a stretcher that they took Clodomiro down into the moat to the firing squad. The stairway, which descends into the moat, hangs from the wall on one side. On the other side, there is just space — not even a handrail. The two-hundred-year-old stone steps, worn down by generations of slaves and prisoners, can be seen even from the end of the galleries. The file of guards which carried Clodomiro descended unsteadily. Almost at the bottom of the stairs, one of the guards stumbled. He let go of the stretcher as he groped to steady himself, and Clodomiro fell onto his wounded legs and tumbled down the last steps. One of the guards told us that they tried to tie him to the post, but he simply couldn’t stay erect. They had to shoot him as he lay on the ground. When they shot him, he too cried, “Down with Communism!”

Clodomiro was perhaps the only man ever executed who was being devoured by worms even before he died.