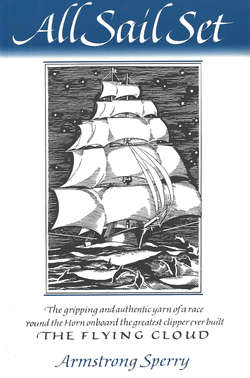

Читать книгу All Sail Set - Armstrong Sperry - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER II

A SHIP IS BORN

AS I HURRIED homeward, I could scarce contain myself. I wanted to shout and jump for joy. A job in Donald McKay’s shipyard! To work all day within sight of the water; to see ships come and go, and to earn three dollars a week!

The wind had risen and the bite of it sent my chin deeper within my greatcoat collar. Sparrows huddled on the roof tops, like Millerites awaiting the call to Judgment. First I must tell my good news to old Messina Clarke. I found him chipping the ice off his front walk, without hat or overcoat. He was as tough as a length of new hemp, and he wielded a rusty hoe with as much vigor as if he were bending sail in the teeth of a nor’easter.

“Cap’n! Cap’n Clarke!” I shouted. “I got it!”

“Got wot?” he grunted.

“Got a job, Cap’n!”

He set down the hoe then and looked up. “Where?”

“With Donald McKay,” I bragged. “You know—the man whose clippers they’re all talking about.”

“Humph, McKay!” growled old Messina, with a sour look.

“Well, don’t you want to hear about it?” I demanded, angling to be invited into the warmth of his study. There a fire was sure to be burning on the hearth and there, I knew, the old man would brew a pot of coffee strong enough to fell a bucko mate.

Without answering, old Messina turned to enter the house. This was his invitation. Otherwise he would have roared, “Home with ye, ye blitherin’ coot, or I’ll lay a marlinespike around yer ears!”

Once inside the narrow study, I threw off my beaver cap and shrugged out of my greatcoat. Here I felt at home, and here I had passed the happiest hours of my life. In one corner stood the revolving globe on which I had traced the course of all the old man’s voyages. Over the mantle hung a model of the Indiaman Aeolus, last of his commands. Beautifully carved and finished in each detail she was, with gold leaf laid on below the water line in place of copper; the pride of the old man’s heart. Three years he had given to the making of her. Maps hung about the walls, and trophies from every corner of the world: headdresses of human hair from the Marquesas; stone gods from the Solomons; whalebone fashioned into strange objects.

Tables and chairs were piled with books over which I had spent long hours in attempting to master such rudiments of navigation as my brain could encompass. In this room I had labored to solve the riddle of Napierian logarithms in order to follow the tables in Bowditch.

“Well,” growled old Messina, dumping a half pound of coffee into a pot and stirring it up furiously with a broken egg and some water, “I’m a-waitin’.”

Here I felt at home and here I had passed the happiest hours of my life …. Tables and chairs were piled with books over which I had spent long hours in attempting to master such rudiments of navigation as my brain could encompass.

“Well,” I began, “I went to see McKay because Father used to say that he was the only man who was one jump ahead—” I got no further.

“McKay!” the old man snorted. “Young upstart, that’s what he is!”

I leaped to the defense of my new god. “Why do you say that?” I demanded.

Old Messina stared at me for a moment in amazement. “Why do I say that?” he mimicked sarcastically. Not often had I challenged his judgment. “Didn’t I stop in at his office one fine day to look at his precious models? ‘Ye’re puttin’ a stem like a bowie knife on them-there ships,’ I says to him. ‘Tain’t natural in a ship.’ And what, thinks you, he answers me back?”

“What, Cap’n,” I muttered, subdued by now.

The old man changed his voice into a genteel imitation of McKay’s speech. “ ‘The East Indiaman has had its day,’ says he to me. ‘These clipper bows that I design will achieve a maximum o’ speed.’ ’Tain’t the shape o’ yer bows that’ll beat them steam paddle boxes,’ I says to him, ‘It’s brains on the quarter-deck.’ ‘It’s both, Cap’n,’ says he; ‘give me quarter-deck brains and my designs and together we’ll trim them all.’ That’s what he says to me. To me that was born on a passage around the Horn. I’ve wrung more salt water out o’ my socks that ever he sailed on!” Messina spat his scorn. “Bows turned inside out that way,” he muttered. “She’ll bury herself in the first ground swell!”

Old Messina, you may observe, was one of the die-hards. Even when the Sea Witch made the record passage of 97 days to ’Frisco the old man had refused to credit it.

Old Messina Clarke.

“Anyway,” I ventured, “McKay is going to pay me three dollars a week, and maybe he’ll let me draw ships, too.”

“Draw ships!” Messina exploded. “It’s high time you was a-sailin’ ’em!”

Needless to say I was disappointed in the way the old man received my good news. For the first time I felt that he had failed me. It didn’t occur to me then that it might be a blow to him to see me turning to someone else for nautical training.

My mother took it differently. “Donald McKay is a splendid man and he was a good friend of your father’s. You mustn’t mind what old Messina says. He’s a little touchy, you know. I think it’s a wonderful opportunity, but I shall be thankful if the association doesn’t lead you into sailing.”

The fact that I must leave school to make my own way in the world did not upset me. What school could have rivaled the interest of the surroundings in which I now found myself? From six o’clock in the morning till six at night I labored over a drawing table in the mold loft of Donald McKay’s shipyard.

My work in the beginning, in all truth, was elementary enough: I was allowed to trace the simpler details of ornament for the great-cabin. Today I realize that it was only the kindness of his heart for the son of a friend that prompted McKay to take me into his office. In those first weeks, if the destiny of the ship and the fate of all who manned her had been dependent upon my efforts, I could not have felt a greater sense of responsibility.

Through our offices filed a procession of shipwrights, chandlers, underwriters, lumbermen, engineers, sailmakers, captains active and retired. I kept my eyes upon my work, for McKay was a hard taskmaster, but I kept my ears apeak, and they missed no detail of all that there was to hear.

Donald McKay not only designed his ships, he superintended their construction as well. When he first began to build, it was the custom to hack frame timbers out of the rough with a broadax; when a timber must be cut lengthwise, it was sawed through by hand, a laborious process and a slow one. Here McKay showed the independence of his mind by setting up a sawmill in his yards to do both these jobs. It was an innovation, I can tell you. The saw hung in a mechanical contraption in such way that the workmen could control the tilt of it and thus get the desired bevel of cut. Once men had had to carry the big timbers on their shoulders; McKay erected a steam derrick to do it for them. It caused a lot of amusement among the scoffers but did the same work in jig time.

So active had the New England shipbuilders become that the seaboard forests were being stripped bare of timber. Men had to look farther for wood. McKay met this problem after his own fashion: he made a full set of patterns for every stick and timber in his ships; these patterns were taken into the northern forests during the winter; lumberjacks felled trees of the necessary number and size. Then over snow and ice the logs were hauled to the rivers before the spring thaws, and down in East Boston his adzes and hammers and his caulking irons rang to high heaven.

Sometimes the poet Longfellow dropped in to pass the time of day. If old Messina hadn’t always snorted at poets and suchlike, I might have paid more attention to Longfellow. But I do remember that after a visit to our yards, he once wrote a poem about a launching, and Donald McKay tacked a copy of it up on the wall of the mold loft. Probably it has never come to your eye, since they tell me that these enlightened days of the twentieth century hold Longfellow something of a fogy with a goodly coating of moss to his back. Maybe so. Anyway, here is the stanza:

Then the Master,

With a gesture of command,

Waved his hand;

And at the word,

Loud and sudden there was heard,

All around them and below,

The sound of hammers, blow on blow,

Knocking away the shores and spurs.

And see! she stirs!

She starts—she moves—she seems to feel

The thrill of life along her keel.

Not bad for a poet, moss or no moss. Once Richard Henry Dana, who wrote Two Years Before the Mast, stopped by for a chat with Donald McKay: a quiet, studious-looking man he was, with little look of the sea about him. Aye, it was all-absorbing to a lad like me, you can imagine.

Up in the mold loft the air was charged with activity. Draftsmen, down on their knees, drew diagonals and trapezoids in chalks on the floor. No one but a shipwright could have made head nor tail to them. McKay hovered over his men like a hawk, his keen eyes catching out any error of workmanship. With mammoth calipers he checked every line that the draftsmen drew, and they trembled lest the master find so much as a quarter-inch difference in their renderings of his plans. Sometimes he paced the floor as we worked, and you knew by the far look in his eyes that he was seeing this ship full-bodied and in her element—the sea. Now and again he’d halt, study the sheaf of plans in his hand, then bend to chalk a correction in the designs on the floor.

Every important timber in the ship—and there were more than two hundred—had been drawn in small scale on these plans. The draftsmen redrew them in chalk on the floor, some fifty times larger. Though the mold loft was 100 feet long by 150 feet deep, it was not vast enough to accommodate all these great drawings; they overlapped and crisscrossed until they would have seemed a Chinese puzzle to a landsman’s eye.

So the Flying Cloud took shape. First the seed which germinated in one man’s mind; then the model by which lesser men could catch the vision of her; then the mechanical drawings that put her into figures of geometry and conic sections. But as I labored there from daylight till dusk, bent over my drafting table and completely happy, those drawings became more in my sight than intersecting arcs and geometric trapezoids: they were the yards and spars of my ship, buffeted by the gales of the Roaring Forties, and I was athwart the t’gallant yard with my feet hooked into the lifts, fisting sail in the teeth of a heroic wind!

It was a great day when the converter was given the order to make his molds. It meant that at last the Flying Cloud was emerging from her chrysalis of drafting paper into tangible form. The converter and his men moved into the loft, puffed up with the sense of their own importance. First they cut thin deal boards into molds, each one of which followed exactly the shape of the chalk drawings on the loft floor. Then as fast as each mold was cut, it was carried off to the neighboring lumberyard where Donald McKay himself picked out timbers of the proper grain and size and marked each one with the number of its mold.

Pileheads had been driven deep into the slip to form a bed for the ship to rest upon. Timbers were laid horizontal-wise across the pileheads. On rugged blocks of oak along the center of the groundways the backbone of the vessel had its beginning. Of solid rock maple were her keel timbers; next, the upward thrust of her stempiece curved from its boxing into the keel; the sternpost was set in its mortise, while amidships the white-oak ribs swelled and rounded.

Fortunately it was a mild winter and no weather was so bad as to keep the men from their appointed jobs. From light till dark the yards hummed with activity. The saws whirred; the derrick groaned its complaint; adze and caulking iron kept up their resounding clamor, while the air was filled with the tang of fresh sawed oak and pine. Wood powder drifted like mist from the pits where the under-sawyers worked; the fires of the blacksmiths glowed in the wind.

In those days men took a pride in their work. The humblest apprentice in the yards seemed to feel that he was engaged upon a great, aye, even a sacred undertaking. For them the Flying Cloud was not just one more ship; she was timber and iron springing into life under their hands. Funny thing—that sense of the reality of a ship which impresses itself upon those who have a hand in her shaping. There was not a workman in the yards who doubted that a living spirit was housed within his handiwork. Just so the sailor believes that it’s the soul of a ship which makes an individual of her. And who can declare that they’re wrong? It is a fact that two ships built after the same plans, in the same yards, by the identical builder, will display wide-differing qualities when they take to sea. The one will prove herself in a gale; the other in light airs. One will be a killer of men on every passage while the other will never start a sheet or lose a spar. No one can deny that such differences exist. Your landsman will declare that it is some slight variation in line of hull or rake of mast or hang of canvas. But the landsman knows naught about these things. The sailor, living close to the elements, understands much that never meets the eye.

The winter months passed. Spring made itself felt in the mildness of the air. Now we could throw open the windows of the drafting room, and the water in the harbor was softer to the eye. The Flying Cloud lay on her strait bed at the water’s edge, grown past all recognition of her beginnings. Nigh a million feet of splendid white oak with scantlings of southern pine had gone into her frame, and over fifty tons of copper, exclusive of sheathing. She was seasoned with salt and “tuned” like a Stradivarius. Duncan MacLane wrote in the Boston Atlas: “Hers is the sharpest bow we have ever seen on any ship.” Men were laying bets on her potential speed, investing their life savings in her cargo. A ship built by Donald McKay to better the record of the Staghound—they couldn’t lose!

Each night on my way homeward I would stop in for a chat with Messina Clarke. While the old man pretended indifference to McKay’s newfangled methods of building, he was consumed by curiosity. I know now, too, that he resented this new world of mine in which he could not wholly share.

After devious circlings, old Messina would arrive at the point he wanted to know. Clearing his throat, he would ask:

“And what might the rake of her masts be, lubber?”

“Alike they’re one-and-one-quarter inches to the foot,” I would answer.

“Humph!” came his snort. “She’ll lose her sticks in the first good blow, mark my words!”

Silence. Then: “And what might the finish of her great-cabin be?” he would question.

“She’s wainscoted with satinwood, mahogany, and rosewood, set off with enameled pilasters, and cornices of gilt work.”

“By the horns o’ Satan!” he roared. His indignation was boundless. “Plain pine with a coat o’ white lead was good enough for my day! Ships was meant to be ships, as men was meant to be men. Whoever did see a man with his hair curled and scent to his coat what was worth a chip on a millrace? Dressin’ a ship up like that! It’s—it’s indecent!”

But despite his scorn, no part of the development of the Flying Cloud escaped his attention or comment. Together we had watched her grow from a tadpole into a whale; keel and rib, floor plank and monkey rail, stem and steering post. I, from the drafting room, where I could see every stick and timber as it swung into place on the stocks, and old Messina seeing it all in my accounts of each day’s activity. For us both the Flying Cloud stood for much more than a ship: for me she was a symbol of romance and eager venture; of the mysterious lands that lay beyond the ocean’s rim; of things longed for and hopes fulfilled. For the old man she was all that the sea stood for in his salty mind; his boyhood; the vasty ventures of his middle years; sunlight and whistling gale.

It was with a feeling of sorrow that we watched each day bringing her nearer completion, as one regrets seeing a babe emerge into a child, child into man. Every handspike hammered into her hull came to echo dully in our ears. We resented the cocky air of the workmen who acted as if the Cloud were their ship when we knew her to be ours alone.

Inevitably there came a day when the last trunnel had been driven, when the whang of mallet and adze was silent, and the whir of the saws had stilled. The figurehead, wrapped about in cotton swathings, was hoisted to its mortise and bolted into place. There was a hush, like a portent. So it might be in the moment before a giant awakes. The Flying Cloud, all glistening black and copper, lay at the water’s edge, alive, eager, straining for the sea. It was her time to go. Her destiny must be fulfilled.

On April 15, 1851, she was launched. Not long ago I came across a yellowed clipping in my sea chest that will give you a better picture of the event than words of mine:

“The ceremony of introducing the noble fabric to her watery home occurred in the presence of an immense crowd of spectators, and she passed to her mission on the deep amid the roar of cannon and the cheers of the people. Visitors were in town from the back country and from along the coast to witness the launch, particularly from Cape Cod, delegations from which arrived by the morning train. The wharves on both sides the stream, where a view was attainable, were thronged with people. Men, women, and children vied with one another to get a look; and men and boys clung like spiders to the rigging of the ships and the sides and roofs of stores and houses, to get a glance at this magnificent vessel. As the hammer of the clock fell at 12, the stroke of a gun at the shipyard announced that the ship had started on her ways, and she pursued her graceful course to the arms of the loving wave that opened wide to receive her …”

The Flying Cloud, all glistening black and copper, lay at the water’s edge, alive, eager, straining for the sea. It was her time to go. Her destiny must be fulfilled.

Aye, it was a great day for us all. Donald McKay, with hollows under his sleepless eyes, watched the launch from a window in his office. As the ship slid down her tallowed ways and came to the staging’s end, the slash of a knife freed the figurehead of its cotton wrappings, and an exclamation went up from the spectators in a vast sigh. The figure of an angel seemed to float on outspread wings, rising slenderly out of the stem, while the sun struck against the gold of the trumpet at her lips like a ringing cry of triumph.

For myself, I knew only a feeling of sorrow as my ship took to water. As soon as her masts were stepped, she was to be towed away to New York. Grinnell, Minturn & Company of that city had purchased her from Enoch Train for $90,000. A sale which, be it said in passing, Enoch Train was never to cease regretting, although the croakers shook their heads in gloomy prediction that Grinnell was sailing both sheets aft for bankruptcy.

I doubted that I should ever lay eyes upon my ship again. No matter how many vessels I might see turned out of the McKay yards, no other would mean so much to me. She was my first love; puppy love, some thoughtless ones call it. No other love strikes its grappling hook so deep into the heart.

It was some weeks later, wnen the Cloud’s masts had been stepped and the riggers had done their work, that the tug Ajax nosed into the harbor. I wanted to shout out my protest! I hoped the tug might ram a rock and sink, and the Captain fall to a watery grave, and all the men be stricken with paralysis! None of these dire events came to pass. The Ajax meant business and she set about it.

As the Flying Cloud was towed out to sea, I stood on the hill behind Messina Clarke’s house, beside the towering figurehead, and wondered how the mermaid could blow her conch on such a mournful day.

“… They placed a silver coin under the heel of your mainmast step, Flying Cloud, to speed you on long voyages. Storms are waiting for you, and seas to batter you. Davy Jones will reach for you and every skeleton in his locker will rattle its bones. But there are spice islands in another sea, waiting for you, Flying Cloud. Only I won’t be there …”

And then I turned away, for I was a big lad by now, going on fifteen, and mighty near to blubbering.

“Cap’n,” I muttered, turning back to the old man, “Cap’n—” then stopped. For Messina Clarke, with the back of one hoary fist, was knuckling a tear out of his own eye!

Since that day, so long ago now, I have come to learn that there is no heart so soft as the sailorman’s, and none more filled with sentiment. Stout hearts, but never hard ones. So we stood there, under a gilded mermaid, an old man and a boy watching a ship being towed out to sea.

What was passing in the old man’s mind, I can never know. For myself, I felt that I had lost a friend.