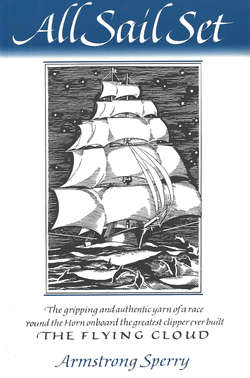

Читать книгу All Sail Set - Armstrong Sperry - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

IT MIGHT be supposed, with sailing ships becoming more and more of a curiosity every year, and with so many excellent books on the subject following one another from the press, that little remains to be told of the famous days of sail. On the contrary, from certain signs of the times, it appears that sea literature is entering upon a new lease of life, and many tales have yet to be published, neither romantic nor sensational, but genuinely truthful and realistic narratives of the lives of deep-water mariners.

The maritime history of New England in the first part of the nineteenth century has certain features not found elsewhere in the world. A stormy, difficult coast; a hardy race of men, who were also born traders; an almost unlimited supply of oak and pine suitable for shipbuilding, and a network of manufacturing centers—all these combined to produce a shipping community second to none. It is not enough to have ships coming into harbor and merchants with cargoes to consign. True maritime prosperity arises when men take naturally, without immediate thought of money making, to ships and shipbuilding, when whole families are so saturated with seafaring thoughts that it becomes the natural way of life for boys to adopt, and the girls accept as part of their existence the absence of their husbands and sweethearts for long voyages.

It was only natural, moreover, that the development of faster and larger vessels should take place along the shores of New England and Canada. This was the most densely settled section of the American continent, and the demand for tonnage was keener here than elsewhere. The discoveries of Bowditch and Maury made possible a speed unknown before. It was not seriously believed that the newfangled steamboats which Samuel Cunard was building would ever compete with sails in transporting cargoes. The cost of fuel was too great. A new design of windship was coming into vogue to maintain the prestige of New England, vessels with long, knifelike bows and a vast spread of canvas, built on the lines of a fish so that speed could be maintained in light winds. The clipper ship was the deep-water man’s answer to the challenge of the steamboat, and when gold was discovered in California, the opportunity came to show the world what he could do. The greatest naval architect of the day was given practically carte blanche by shipowners to design the fastest and finest ship possible. Donald McKay produced many magnificent vessels, but his shipyard never gave birth and being to anything that captured the imaginations and the hearts of men so completely as did his Flying Cloud.

Flying Cloud had a long career for a ship of her class. The tremendous spread of canvas and the relentless driving by their captains in search of a record, strained all the clippers so much that they were soon used up. They were, as shipwrights say, unduly spent. Compare the few short years of such ships with Erin’s Isle, built in 1877 in my father’s yard at Saint John, N. B., about the same tonnage and rig as Flying Cloud, but not designed for speed. She sailed the seas for nearly forty years and then became a coal hulk, not because she was worn out, but for lack of charters. The driving of the clipper ships was the last desperate attempt of sail to compete with steam. There was something heroic about that challenge. But as H. M. Tomlinson says somewhere, rather grimly, ships make time but steamers keep it. There was, in the long run, no possible chance for the windship. She went down gloriously, a thing of beauty that had outlived her day.

Flying Cloud is the heroine of this story of a boy’s start at sea. Enoch Thacher, who tells the story in his old age, is the son of a worthy merchant who had lost his fortune when Empress of Asia went down with all hands off Cape Horn. To help his mother, Enoch goes to Donald McKay, who knew his father, and takes a position in the drafting room in McKay’s yard while Flying Cloud is on the stocks. His love for ships and the sea has been fostered by his old friend, Messina Clarke, a shellback of the old school, who looked with distrust upon McKay’s long, concave clipper bows, even when the ships made record passages. Enoch becomes a devoted worshiper of McKay, and the dream of his life is to go to sea. At fifteen his vocation is plain before him. He has learned every rope and spar in the shipyard. He has seen Flying Cloud go out in ballast to load in New York for San Francisco and China. To his joy, Donald McKay recommends him for a cadetship and wins over his widowed mother to consent. Enoch takes the coach to New York and joins the Cloud in South Street.

The pattern of all books that tell of boys going to sea is no doubt Two Years Before the Mast. But Richard Henry Dana was a special case. He was a young Harvard man who took a voyage around the Horn a hundred years ago. He was not a sailor in the professional sense any more than are the young collegers who sail as summer cadets in our steamers. This is not to depreciate the achievement of Dana as a seaman or the classic that he wrote on his return. It is merely to point out that ships are not manned by collegers, but by boys and men who have so great a passion for the life that they keep on with it in spite of all the hardships and privations. It is a passion which for good or ill is born in many boys, even though they live far inland and have no immediate contact with the sea. When they grow up in a shipping community, the craving becomes irresistible. The sea calls and will not be denied.

In one sense this story of young Enoch Thacher’s voyage around the Horn is not fiction at all. The test of good fiction is that it shall produce the impression of truth and this test Mr. Sperry’s story of Enoch Thacher’s adventures passes triumphantly. The youngest boy who has learned to read will have his nose in this book until he has finished it or his elders have taken it away from him to read themselves. There is a most wholesome atmosphere of realism and truth in this book. Many sea writers are out, not to tell the truth about seafaring, but to make sensational disclosures. As one who comes from a seafaring and shipbuilding family, the legends of sailing ships have always appeared to me heavily loaded with bunkum. The notion that every captain was a hard-boiled autocrat and every first mate a bloodthirsty lunatic has always been a shade too fantastical for one whose relatives since 1840 have been masters and mates in sail and steam. That going to sea was no picnic in the days of the windships is doubtless true, but the life appealed to those who had a bent that way, and mates who crippled and murdered their men were in a minority at all times. They received more publicity than decent officers, and their deeds have always appealed to newspapermen and writers of sea stories as better adapted to sensational tales.

This sort of exaggeration is excellently avoided in Mr. Sperry’s dashing tale. Everyone on board, from Captain Josiah Perkins Creesy to the boys in the half deck, is a genuine and authentic character. The action that goes on in the narrative is entirely rational and free from the sensational savagery which has been so popular in so many sea stories. As an example, who does not know the sea yarn in which the trembling, green boy is ordered aloft as soon as he is on board? How often have we read of the bucko mate whose idea of efficiency and skill is to lay out several of his men with quite incomprehensible brutality? Mr. Sperry’s story is quite different. It is all the more exciting because words and actions ring true. The autocratic captain is there, but he is a human being. Even the bucko mate is there, but what happens to him must be read in the book. The story is full of carefully concealed ingenuity and inventiveness. The conversation between the captain and the mate while arguing over the handling of the ship is one of the most convincing pieces of realism I have read during a number of years of reading sea literature. The fight between Enoch Thacher and the sea lawyer, Jeeter Sneed, is first-rate. Jeeter, a common type in sea fiction, and usually so overdrawn as to be incredible, is well done here. The mutiny, one of the most easily bungled scenes in any book of this kind, is the real thing. Any boy who does not revel in the Neptune initiations which take place while Flying Cloud is crossing the Equator, must be hard to please.

Those days, of course, are gone, never to return. The boy of today who goes to sea has another tale to tell. He does not have to go aloft to fist canvas in a gale nor does he ever see Cape Stiff in winter. It would be foolish to imagine, however, that he has to be any less courageous or ready-witted. At any moment he may be tested. The sea will never be tamed or civilized. The larger and more complex the vessel the more severe the demands upon the personnel. Behind the most ingenious mechanical inventions there must ever be a man’s courage, integrity, and presence of mind. All the fine qualities of the human mind and character which are depicted in this tale of Flying Cloud’s maiden voyage around the Horn are needed today. Boys with the right stuff in them will take Enoch to their hearts and treasure with pride and affection the memory of that lovely ship.