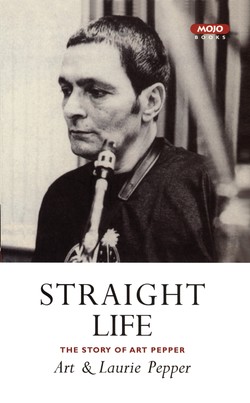

Читать книгу Straight Life: The Story Of Art Pepper - Art Pepper - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| 1 | Childhood1925–1939 |

MY GRANDMOTHER was a strong person. She was a solid German lady. And she never would intentionally have hurt anyone, but she was cold, very cold and unfeeling. She was married at first to my father’s father and had two sons, and when he died she remarried. And the man that she married liked her son Richard and didn’t like my father whose name was Arthur, the same as mine.

My father’s stepfather beat him and just made life hell for him. Richard was the good guy; he was always the bad guy. When he was about ten years old he couldn’t stand it anymore, so he left home and went down to San Pedro, down to the docks and wandered around until somebody happened to see him and asked him if he would like to go out on a ship as a cabin boy, and so he did. That was how he started.

He went out on oil tankers and freighters doing odd jobs, working in the scullery, cleaning up, running errands. Because he left home, naturally his schooling was stopped, but he always had a strong desire to learn, so he began studying by himself. He was interested in machinery and mathematics. He studied and kept going to sea and eventually, all on his own, he became a machinist on board ship. He went all over the world. He became a heavy drinker, did everything, tried everything. He lived this life until he was twenty-nine years old, never married, and then one day he came into San Pedro on a ship be-longing to the Norton Lilly Line; they’d been out for a long time; he had a lot of money, so he went up to the waterfront to his usual bars. And going into one of them he saw a young girl. She was fifteen years old. Her name was Mildred Bartold.

My mother never knew who her parents were. She remembers an uncle and an aunt who lived in San Gabriel. They were Italian. They seemed to love her but kept sending her away to convents. Finally she couldn’t stand the convents anymore, so she ran away, and she ended up in San Pedro, and she met my father.

She was very pretty at the time with that real Italian beauty, black hair, olive skin. My father had gotten to the point where he was thinking about settling down, getting a job on land, and not going to sea anymore. They met, and he balled her, and he felt this obligation, and I guess he cared for her, too, so he married her.

So here she was. She had finally gotten out into the world and all of a sudden she’s married to a guy that’s been all over, has done all the things she wants to do and is tired of them, and then she finds herself pregnant. She wanted to drink, look pretty, have boyfriends. She was very boisterous, very vociferous. She would get angry and demand things, she wouldn’t change, she wouldn’t bend. Naturally she didn’t want a baby. She did everything she could possibly do to get rid of it, and my father flipped out. That was why he married her. He wanted a child.

She ran into a girl named Betty Ward who was very wild. Betty had two kids, but she was balling everybody and drinking, and she told my mother what to do to get rid of the baby. My mother starved herself and took everything anybody had ever heard of that would make you miscarry, but to no avail. I was born. She lost.

I was born September 1, 1925. I had rickets and jaundice because of the things she’d done. For the first two years of my life the doctors didn’t think I would live but when I reached the age of two, miraculously I got well. I got super healthy.

During this period we lived in Watts, and my father continued going to sea. He hated my mother for what she had tried to do. She was going out with this Betty; I don’t know what they did. They’d drink. I’d be left alone. The only time I was shown any affection was when my mother was just sloppy drunk, and I could smell her breath. She would slobber all over me.

One time when my father had been at sea for quite a while he came home and found the house locked and me sitting on the front porch, freezing cold and hungry. She was out some-where. She didn’t know he was coming. He was drunk. He broke the door down and took me inside and cooked me some food. She finally came home, drunk, and he cussed her out. We went to bed. I had a little crib in the corner, and my dad wanted to get into bed with me. He didn’t want to sleep with her. She kept pulling on him, but he pushed her away and called her names. He started beating her up. He broke her nose. He broke a couple of ribs. Blood poured all over the floor. I remember the next day I was scrubbing up blood, trying to get the blood up for ages.

They’d go to a party and take me and put me in a room where I could hear them. Everybody would be drinking, and it always ended up in a fight. I remember one party we went to. They had put me upstairs to sleep until they were ready to leave. It was cloudy out, and by the time we got there it was night. I looked out the window and became very frightened, and I remember sneaking downstairs because I was afraid to be alone. They were all drinking, and this one guy, Wes—evidently he’d had an argument with his wife. She went into a bathroom that was off the kitchen and she wouldn’t come out; there was a glass door on this bathroom, so he broke it with his fist. He cut his arm, and the thing ended up in a big brawl.

My parents always fought. He broke her nose several times. They realized they couldn’t have me there. My father’s mother was living in Nuevo, near Perris, California, on a little ranch, one of those old farms. They took me out there. I was five. And that was the end of my living with my parents and the beginning of my career with my grandmother. I saw my grandmother, and I saw that there was no warmth, no affection. I was terrified and completely alone. And at that time I realized that no one wanted me. There was no love and I wished I could die.

Nuevo was a country hamlet. Children should enjoy places like that, but I was so preoccupied with the city and with people, with wanting to be loved and trying to find out why other people were loved and I wasn’t, that I couldn’t stand the country because there was nothing to see. I couldn’t find out anything there. Still, to this day, when I’m in the country I feel this loneliness. You come face to face with a reality that’s so terrible. This was a little farm out in the wilderness. There was my grandmother and this old guy, her second husband, I think. I don’t even remember him he was so inconsequential. And there was the wind blowing.

It was a duty for my grandmother. My father told her he would pay her so much for taking care of me; she would never have to worry—he always worked and she knew he would keep his word. I think she was afraid of him, too, for what she had done to him. For what she had allowed to be done to him when he was a child.

My grandmother was a dumpy woman, strong, unintelligent. She knew no answers to any problems I might have or anything to do with academic type things. She was one of those old-stock peasant women. I never saw her in anything but long cotton stockings and long dresses with layers of underclothing. I never saw her any way but totally clothed. When she went to the bathroom she locked the door with a key. Anything having to do with the body, bodily functions, was nasty and dirty and you had to hide away. I don’t know what her feelings were. She never showed them. She had a cat that she gave affection to but none to me. I grew to hate the cat. My grand-mother was—she was just nothing. There was no communication. Whenever I tried to share anything at all with her she would say, “Oh, Junior, don’t be silly!” Or, “Don’t be a baby!” I had a few clothes and a bed, a bed away from her, a bed alone in a room I was scared to death in. I was afraid of the dark.

I was afraid of everything. Clouds scared me: it was as if they were living things that were going to harm me. Lightning and thunder frightened me beyond words. But when it was beautiful and sunny out my feelings were even more horrible because there was nothing in it for me. At least when it was thundering or when there were black clouds I had something I could put my fears and loneliness to and think that I was afraid because of the clouds.

We moved from Nuevo to Los Angeles and then to San Pedro, and during the time of the move to L.A. the old guy disappeared. I guess he died. My parents separated and they came to see me on rare occasions. My mother came when she was drunk. My father always brought money, and every now and then he’d spend the night. When he came I’d want to reach him, try to say something to him to get some affection, but he was so closed off there was no way to get through. I admired him, and I thought of him as being a real man’s man. And I really loved him.

My father was trim, real trim. He had a slender, swimmer’s body. He had blue eyes, blonde hair. He had a cleft in his chin. He had a halting, faltering voice, but pleasant sounding, and a way about him that commanded respect. He’d been a union organizer and a strike leader on the waterfront, and he had a bearing. People listened to him. I nicknamed him “Moses” because I felt he had that stature, that strength, and soon everybody in the family was calling him that.

My father was tall, he was strong, and I felt he thought I was a sissy or something. I abhorred violence, but in order to try to win his love I’d go to school and purposely start fights. I fought like a madman so I could tell him about it and show him if I had a black eye or a cut lip, so he would like me. And when I got a cut or a scrape in these fights I would continue to press it and break it open so that on whatever day he came it would still be bad. But it seemed like the things he wanted me to do I just couldn’t do. Sometimes he’d come when I was eating. My grandmother cooked a lot of vegetables, things I couldn’t stand—spinach, cauliflower, beets, parsnips. And he’d come and sit across from me in this little wooden breakfast nook, and my grandmother would tell me to eat this stuff, and I wouldn’t eat it, couldn’t eat it. He’d say, “Eat it!” My grandmother would say, “Don’t be a baby!” He’d say, “Eat it! You gotta eat it to grow up and be strong!” That made me feel like a real weak-ling, so I’d put it in my mouth and then gag at the table and vomit into my plate. And my dad was able, in one motion, to unbuckle his belt and pull it out of the rungs, and he’d hit me across the table with the belt. It got to the point where I couldn’t eat anything at all like that without gagging, and he’d just keep hitting at me and hitting the wooden wall behind me.

My mother was going with some guy named Sandy; he played guitar, one of those cowboy drunkards that runs around and fights. I was going to grammar school and I remember once she came when I was eating lunch in the school yard. She went to the other side of the fence and called me. She was wearing a coat with a fur collar. I was scared because my father had told me, “Don’t have anything to do with her! She didn’t want you to be born! She tried to kill you! She doesn’t love you! I love you! I take care of you!” But he didn’t act like he loved me. I left the yard, and she took me in a car. I said, “I can’t go with you.” But she took me anyway. She smelled of alcohol and cigarettes and perfume and this fur collar, and she was hugging me and smothering me and crying. She took me to a house and everybody was drunk. I tried to get away, but they wouldn’t let me leave. She kept me there all night.

When I was nine or ten my dad took me to a movie in San Pedro: The Mark of the Vampire. It was the most horrible thing I’d ever seen. It was fascinating. There was a woman vampire, all in white, flowing white robes, a beautiful gown, and she walked through the night. It was foggy, and it reminded me of the clouds. In the movie, whoever was the victim would be in-side a house. The camera looked out a window and there was the vampire: there she would be walking toward the window.

I had a bedroom at the back of my grandmother’s house, and my window looked out on the backyard. There was an alley and an empty lot. After this movie, whenever I got ready for bed, I could feel the presence of someone coming to my window. I would envision this woman walking toward me. I started having nightmares. She had a perfect face, but she was so beautiful she was terrifying—white, white skin, and her eyes were black, and she had long, flowing, black hair. She wore a white, nightgownish, wispy thing. Her lips were red and she had two long fangs. Her fingers were long and beautiful, and she held them out in front of her, and she had long nails. Blood dripped from her nails and from her mouth and from the two long fangs. It seemed she sought me out from everyone else. There was no way I could escape her gaze. I’d scream and wake up and run to my grandmother’s room and ask her if I could get in bed with her, and she’d say, “Don’t be silly! Don’t be a baby! Go back to bed!”

This went on and on. I’d have nightmares and wake up screaming. Finally my grandmother told my dad and he took me to a doctor. The doctor gave me some pills to relax me, and it went away. But I kept having the fears. If I went to open a closet door I’d be scared to death. If I went walking at nighttime I’d see things in the bushes.

I’d wander around alone, and it seemed that the wind was always blowing and I was always cold. San Pedro is by the ocean, and we lived right next to Fort MacArthur. Maybe during the First World War there was a lot of action there, but around 1935 it was just a very big place staffed by a few soldiers. It was on a hill, and you could see the ocean all around, and there was a lot of fog and a lot of weeds and trees and brush and old barbed wire, and there was a large area that had been at one time, I think, a big oil field. They had huge oil tanks that went down into the ground very deep, overgrown with weeds. I used to go through the fence and wander around the fort. I’d climb down into these oil things.

Closer to the water they had big guns, disappearing guns, set in cement and steel housings. Every now and then they’d fire them to test them, and they’d raise up out of the ground. But most of the time they were quiet, and I’d sneak around and climb down onto the guns. Down below they had giant railroad guns, cannons, and anti-aircraft guns that they’d practice on; you could feel them going off.

On weekends I’d walk down the hill to a place called Navy Field, where there were four old football fields with old stands. The navy ships docked in the harbor, and the sailors had games, maybe four games going at once. I’d go down alone and sit alone in the stands and watch. Once I was walking under the stands to get out of the wind, and I looked up and saw the people. And the women, when they stood up, you could see under their dresses. That really excited me, so I started doing that, walking around under the stands on purpose to look up the women’s dresses.

I built up my own play world. I loved sports, and I’d play I was a boxer or a football player. I even invented a baseball game I could play alone with dice, but boxing was the one I really got carried away with. At that time Joe Louis was coming up as a heavyweight. I would go out in the garage and pretend I was a fighter. I had a little box I sat on. I’d hear an imaginary bell and get up in this old garage and fight, and it was actually as if I was in the ring. Sometimes I’d get hit and fall down and be stunned, and I’d hear the referee counting, and I’d get up at the last minute, and just when everybody thought I was beaten I’d catch my opponent with a left hook. And then I’d have him against the ropes. I’d knock him out, and everybody would scream and throw money into the ring and holler for me, and I’d hold my hands together and wave to the crowd.

I played by myself for a long time and then, much as I hated to be with other kids, because I felt I wasn’t like them, they wouldn’t like me, I wanted to play sports so bad I overcame that and started playing in empty lots, and I was extremely good at sports. I was good in school, too. My drafting teacher in junior high said I really had a talent, and my father dreamed that one day he’d send me to Cal Tech here or Carnegie Tech back east so I could do something in mathematics or engineering.

My mother’s side of the family was very musical. Her aunt and uncle—I think their last name was Bartolomuccio, shortened to Bartold—had five children. They all played musical instruments. The youngest boy was Gabriel Bartold, and as a child he played on the radio, a full-sized trumpet. He’d put it on a table and stand up to it and blow it.

The Bartolds lived in San Gabriel in a big house. In the back they had a lath-house, an eating place with a big round table. I remember going there several times and all the activity in the kitchen with the aunts and I don’t know who-all making pasta; they made the most fantastic food imaginable. The men drank their homemade wine and ate and ate and ate, and the children were very attentive to the adults. I was very young, and the only thing I really remember is the daughter who was an opera singer. I remember hearing her sing and how pretty she was. She looked like a little angel, and she sang so beautifully with the operatic soprano voice.

I loved music, and when I passed a music store and saw the horns glittering in the window I’d want to go inside and touch them. It seemed unbelievable to me that anybody could actually play them. Finally I told my dad I just had to have a musical instrument. I wanted to play trumpet like my cousin Gabriel. My dad agreed to get somebody to come out and see what was happening with me. He found this man somewhere, Leroy Parry, who taught saxophone and clarinet, and brought him out to the house. In playing football I had chipped my teeth. Mr. Parry looked at my mouth and said I would never be able to play trumpet well because my teeth weren’t strong. He said, “Why don’t you play clarinet? You’d be excellent on clarinet. Give it a try.” I still wanted to play trumpet, but I figured I’d better take advantage of what I had, so I started lessons on clarinet when I was nine years old.

Mr. Parry didn’t play very well, but he was a nice guy, short and plump with a cherubic face, warm, happy-go-lucky. He had sparkling little eyes. You could never imagine him doing anything wrong or nasty or unpleasant. He invited me to his house for dinner a couple of times and I met his wife. She liked me, and they had no children of their own, so she would send me candy that she made. Mr. Parry was like another father to me, and I used to love talking to him. That’s what our lessons were. None of them had anything to do with technicalities or the learning of music. It was just talking, having somebody to talk to. And I never had to practice. Just before Mr. Parry came I’d get my clarinet out and run through the lesson from the previous week. He’d think I’d been practicing the whole time. When I did play I played songs. I played what I felt. I didn’t want to read anything or play exercises.

My father lived nearby. He was working as a longshoreman, and he lived with a woman named Nellie as man and wife. He never married her. He’d visit us and pay the bills. When it was time for school he’d give my grandmother money to get me a few clothes. He drank all the time, too. He used to get mean sometimes; he’d get loud and talk on and on and recite “The Face on the Barroom Floor” and all kinds of weird things.

After I started playing the clarinet my father would come and take me down to San Pedro to the bars. I’ve been there lately and the place is all cleaned up, but at that time, down by the waterfront, the whole area was nothing but bars, and there were fishermen, Slavonians, Italians, Germans—almost every nationality known was in those bars. A few had entertainment, a beat strip show, but most of them were just places guys went to hang out and talk. They weren’t the kind of bars women would go in or that hustlers were at. They were men’s bars, where they’d drink and talk about fishing and the waterfront and driving winches and their problems with management, to talk about the union. They were real tough guys; they were all my dad’s friends. He would take me to several different bars, sit me up on the bar, and make me take out my clarinet and play little songs like “Nola” and “Parade of the Wooden Soldiers” and “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love,” “The Music Goes Round and Round,” “Auld Lang Syne.” The guys would ask for other songs, and I’d play them, and they’d listen. My father would stand right by me and stare at them and nod his head—like they’d better like it or he’d smack ‘em in the mouth! And he was a big guy, and he’d be drunk. I got the feeling that they did like it because I was his boy. They liked boys. I was his boy: “That’s Art’s boy. He plays nice music.” “Yeah, nice boy. Play that thing, boy!” They’d pat me on the back. They’d grab my arm and shake my hand—almost hurt my hand they were so rough: “You just keep it up, boy. You don’t want to be like us.” I was like their child. All their children. “You keep that up and you won’t have to do like we do.” And they would have fingers missing, and some guys would have an arm gone. Things would drop on them and they’d lose legs, feet, fingers. I could get away from that and be respectable and not have to get dirty and get hurt and work myself to death. And so they’d drop a dollar bill in my hand or fifty cents or a silver dollar. I’d end up with fifteen, twenty dollars just from these guys, and my dad never took the money from me. He said, “That’s yours. You earned that.” I always felt scared before I played, but after I did it I was proud and my dad was proud of me.

My grandmother was always talking about Dick, her son, the favorite. According to my dad Dick never helped my grand-mother at all, never brought her anything, never gave her any money, but she thought he was just great and went on and on about how good he was and how bad my dad was. My dad sup-ported her. One day my dad came over and there was talk about paying some kind of insurance for her. He felt that Richard should pay part of it. My dad was drinking, and he decided to go over and see Dick—“Dicky Boy” he called him. He just hated him.

Dick was a plain-looking man. He had dull-colored, hazel eyes; he was a dull person, nondescript and withdrawn. But he always felt that he was right. He always considered himself a good person. Maybe he was. My dad had got him a job as a longshoreman and had done nothing but good for him, but he said Dick had never shown any appreciation.

We went over there, me and my dad. We went inside. He started talking to them. Dick’s wife’s name was Irma, and she was just like him, thin, with no beauty, dull, lightish hair, faded eyes. Everything was faded about both of them. My dad tried to reason with them, tried to find out if they would pay anything. Irma said, “No! She’s taking care of your brat: you pay it!” They got into a terrible argument. When they started hollering I got scared; I ran out to the car; but they were getting so crazy I felt something terrible was going to happen so I ran back, grabbed my dad, and tried to pull him out of the house. I got him to the car but he was too insane to drive. I opened the door and pushed him into the passenger side. He had just started teaching me how to drive. Dick ran out of the house with a big hammer, and when my dad saw him coming he tried to get out of the car to get at him, but I started the car up, praying I could get it going, trying to hold on to my dad at the same time. He’s screaming out the window at them, and Irma’s just screaming on the lawn, and here comes Dick with this hammer. By a miracle I was able to start the car. As Dick saw it moving he threw, and I pulled out just as the hammer hit the window in the back. It hit right where my dad’s head would have been and shattered the glass. We got away. I looked over at him and saw that he was cut, there was blood on his face, and he was still raging about what he was going to do to Dick. Then he stopped. I guess he realized what had happened—that I was driving the car and had possibly saved his life or stopped him from killing. He might have killed both of them.

I drove back to my grandmother’s house, and she wasn’t there. I took him inside. I led him into the house and made him go into the bathroom and sat him down on the toilet and got a washrag. During the ride he had looked at me while I was driving, and I felt that he was seeing me for the first time. And I felt really good that I had done something that was right. I wiped the blood off his face. He wasn’t cut bad, and he looked at me, and that was the first time I ever felt I had reached him at all. I felt good about myself and I felt that he loved me.

Right after that my grandmother came home and broke the spell. He looked at her and realized how she was. I realized how she was. He started raving at her about her Dicky Boy, and I remember cussing her out myself, telling her that her Dicky Boy wouldn’t pay a penny, that he’d tried to kill my dad, that I would kill him, that she was an unfeeling, rotten, ungrateful bitch. She flipped out at both of us. She didn’t care anything at all about him being cut: “How dare you go over there and bother Richard and his wife?” She kept at him and at him, ranking him and goading him, and finally he grabbed her and started to strangle her. Probably all his life he’d wanted to kill her. She certainly deserved to be killed by him, and I had the feeling of wishing that he would kill her, thinking it would maybe free me. She wouldn’t be there and something else would have to be done with me. Maybe he would have to take me to live with Nellie, who was warm and nice and feminine and smelled pretty. And so, for this moment, I was hoping he’d kill her, but all of a sudden I realized what would happen to him, so I grabbed him, and finally he let her go, and she ran screaming out into the street.

(Sarah Schechter Bartold)* My husband was born in Italy. I think he said he had four sisters, but maybe there were three. Two were living when I went there many years ago. I couldn’t say a word. They brought a chair outside. They didn’t invite me in. They were country people, very suspicious.

My husband went to study for the priesthood when he was a young man, but he didn’t like the things he saw going on there. He came to this country, and he was a waiter. He also worked in the coal mines. When I met him he was an insurance man. We met back east. I worked daytimes, and then I went with him to all his prospects at night. But I actually never got, out of fifty-eight years with him, more than he told me. And what difference does it make?

I don’t remember anything about Ida [Mildred Bartold, Art’s mother]. She was seven or eight when she came to us. She was pretty, but she was a terrible little troublemaker right from the beginning. She was a liar, a little liar. But I really don’t remember why she was sent to live with us. Maybe they felt that she would do better in America. As far as I knew she was one of my husband’s sisters’ children. She was a little liar, and that’s the whole story. A child who fibs can do an awful lot of damage, especially when you have little children of your own. She lied about all sorts of things, about the other children—“This one did that.” And they were younger than she was, so I thought it best not to have her around. But why stir up the past and cause her son to have hard feelings about her? She was his mother. Was he her only child? Did he inherit anything when she died? She had nothing to leave? I remember her mostly as a terrible fibber.

(Thelma Winters Noble Pepper) Arthur Senior, “Daddy,” was born in Galena, Kansas, and then I think they went to this Missouri mining town. Grandma’s [Art’s grandmother’s] first husband worked in the lead mines. And it was a real sad thing there because her husband, I think his name was Sam Pepper, was a periodic drunkard. Every weekend when he got paid, he’d go to the saloon to cash his check, and then usually there was nothing left. So this one time, they were visiting Sam’s sister’s family, and this sister’s husband and Sam, they both got drunk, and the sister called the police, who took ’em both to jail, and I think they must of give ’em a thirty-day sentence. And while he was in jail, the place where Grandma lived—they evicted her. She had four or five children at that time (one had just died), and there wasn’t no place for her to go, so they sent her to the poor farm, she and the children. And she was expecting then. She was carrying her twins. They told her, “You know that you can’t keep your children here. They’ll have to be put up for adoption.” She said no way was she going to let her children be put up for adoption, so she went back to where they had been living. She knew an old man that had a run-down, old chicken house. She asked him if she could move in there, and he told her that if she thought she could make that livable, she could have it, and she did. When Sam come out of jail he didn’t look for her. He just stayed away. He just decided to beat it. So that ended that, and that was two months before her twins was born. This all gives you an idea of why Grandma was like she was.

The twins was only three weeks old when she went to work. She and her sister-in-law took in washing together. And the boys—the sister had a boy about Daddy’s age—they’d deliver and pick up. I guess this was in 1895. Daddy would have been about nine years old.

When the twins was fifteen months old they got—at that time they called it membranous croup, but now we know that it was diphtheria. So one of ’em died, and they took him away to be buried, and then the second one got so sick it couldn’t breathe, so she’d walk it, day and night. Fifteen days apart they died. And this last one, Grandma was so wore out with taking care of them for so long, the neighbors induced her to lay down and take a nap. She washed the dead baby and dressed him and put him on a pillow on her sewing machine. While she was asleep, the authorities came in and took the baby, didn’t even wake her up. And that affected her tremendously. When she was here with me and Daddy, dying, she lived that again. One day I heard her crying and I went in there. She was crying just fit to break her heart, and she said, “Oh, why didn’t they wake me? Why did they take him away without waking me?” She didn’t even get to attend the funeral of that second baby.

After that I think she run a kind of boardinghouse for miners. At that time women couldn’t get jobs like they can now. Joe Noble was one of the boarders. Then when Joe started a butcher shop, she helped him in the butcher shop. They decided to get married, and that’s when Joe come out here to California. They were married in 1913.

Daddy didn’t live with them. When he was growing up he spent most of his time on his uncle’s ranch back in the middle west somewhere. Daddy never went to school beyond the fifth grade. Then he went to work. I think he was seventeen when he joined the merchant marine. I don’t know when it was that he lost his eye. Every once in a while he got tired of being at sea, and he’d take a stateside job. He was working on a bean huller, and he got a bean hull in his eye. That put it out. You couldn’t tell it on him. He was the handsomest man I ever saw. I knew him for years before I knew that eye was no good.

Well, Daddy’s stepfather just tolerated him. They didn’t have no open quarrels that I know of. When Daddy’d come to port, San Pedro, he’d go to see them, but he never stayed overnight. His home port was San Francisco, so he’d come down here to see his mother and say hello and goodbye. He loved his mother very devotedly, but she didn’t care too much for him because she hated anybody that drank to excess and Daddy always drank to excess. Dick was her favorite. He didn’t drink at all, and when her other children died, he was the baby. But, anyhow, Dick was a very affectionate, loving person, see, and Daddy wasn’t. Daddy was kinda standoffish, like her. Well, Daddy thought when he supported her and took care of her, that showed his love. He didn’t do a lot of talkin.’ That was the way it was. And I know when she died—Oh, my—he’d sit in that chair there and cry like a baby. He says, “Why couldn’t she tell me she loved me? Just once. Why couldn’t she tell me she loved me?” All three of ’em: there was Grandma, and Daddy, and Junior; they didn’t communicate with each other.

I was married to Shorty—that was Daddy’s stepbrother—in 1920; Johnny was born in October of 1921; and it was March of the following year that I first saw Daddy. He’d just come by for a few minutes, said hello to Grandma, and was gone. And the next time he came in port, my second baby, Buddy, was about six months old, so that was two and a half years later. He come up to see Grandma again, but this time he brought Millie [Mildred Bartold, Art’s mother] with him. That would be 1924, when they got married. Well, Millie fell in love with my Buddy. He was one of those pink and white babies, all soft and cuddly, you know. She wanted a baby. She didn’t figure on Junior [Art] being sickly and hard to take care of.

Millie said she was born back east in New Jersey or New York, and her uncle and his wife, the Bartolds, brought her to California when she was just a little girl. Her real name was Ida. She didn’t know her last name. She’d got a lot of sisters and brothers somewhere. Well, they made a regular little doll of her. Her slightest wish—they got it for her, until they had kids of their own. Then her name was mud. Her aunt wasn’t very good to her after she had children of her own. She’d accuse Millie of doing something, and if she said she didn’t do it, she wasn’t allowed nothing to eat until she admitted she did it. Millie said she went three days one time without anything to eat because she knew she hadn’t done what she was accused of, but she finally told her aunt she did just to get out from under. Then she ran away from home. She ran away a lot of times, and that’s why, I think, the Bartolds finally put her in a convent school. But she ran away from there, too. For a while she was put in a foster home; she was very happy there. But then she met this woman, Mildred Bayard. Millie must have been about fourteen then. This woman wanted Millie to go with her to one of the Harvey Houses out in the desert—I think it was Barstow—as a waitress. I don’t know what kind of experience she had out there, but she run away from there, too, and she went down to [San] ’Pedro to be a waitress.

She was looking for the employment office, and she stopped Daddy on the street to ask him where it was, and he said he’d take her there. He did, but the next day he got her a job with somebody he knew that run a restaurant because he was very well known in ’Pedro. So, let’s see. The first day she met Daddy. The second he got her a job. And then he asked her how old she was. When she told him she was fifteen, she said he got as white as a sheet. The next day they went up to Los Angeles and got married at some Bible college. She gave her name as Mildred Bayard on the marriage license. And then he brought her home to Grandma.

Daddy thought that if Millie could stay with Grandma while he was sailing—at that time he was sailing between ’Pedro and Seattle on a lumber boat. . . But she didn’t get along very good. She was a nice, friendly girl, you know; Italians usually are. And the family wasn’t very nice to her, the Noble family. They were very clannish, and they didn’t seem to take to her too good. She didn’t know what to do with her time, and I think she did things she shouldn’t have. Anyhow, after a couple of trips, Daddy decided that that wouldn’t do. He’d have to come stateside. That’s when he went to work in a machine shop. I was living in Watts then, and I kinda lost track of ’em until Junior was born.

Oh, my! Poor little thing! He had rickets and yellow jaundice when he was born, and he was so skinny that his hands and his feet looked like bird claws. When he was three or four months old! Couldn’t get nothing to agree with him. I don’t know if she couldn’t or if she didn’t want to, but Junior was a bottle baby. I don’t imagine she had any milk anyway. She didn’t eat right. Junior couldn’t assimilate cow’s milk. They had him to half a dozen different doctors, and they all told ’em the same thing: “He can’t live.” They took him to Children’s Hospital in L.A., and the doctors gave them a formula for barley gruel. It had to be cooked all day, and in that she put Karo syrup and so much dextro-maltose, and that agreed with him. But he was still awfully skinny and they couldn’t bathe him in water—he was too weak. The doctor told them that if they bathed him in olive oil, that would nourish him, too. He looked like death warmed over.

Daddy and Millie had lots of fights about Junior not being Daddy’s. He was sailing when she got pregnant, and Junior would have either had to be two weeks early or two to three weeks late. And so this Betty Ward, a friend of Millie’s, smart-aleck woman that she was, she was there when Junior was born, and she said to the doctor, “Is he a full-term baby?” The doctor said, “Yes, he came right on time.” So there was that question. But in time, Daddy realized that Junior had to be his. There were too many features the same. You know them turned up toes that Junior has? And Daddy’s arms are shaped, were shaped, here just exactly like Junior’s.

But Millie was unfaithful. Might as well say it. I remember when me and Shorty lived in the big house, and she and Daddy lived in the back. Daddy worked swing shift, and she’d go out, and she asked me to listen for Junior in case he woke up. She got home one night just by the skin of her teeth, just soon enough to get her clothes off and jump in bed before Daddy got home. Scared her to death.

This Betty Ward had several children and they were all mean as could be to Junior. They were all older than he, and they would tease him just to hear him holler ’cause he’d make a real big commotion when he was upset about anything. They’re the ones that got him afraid of food touching on a plate. Millie and Betty would go tomcattin’ somewhere and leave him with these kids. There’d be plenty of food for the kids, but when it come time to eat, they wouldn’t let Junior have any. And when they’d finally decide to give him something to eat, they’d put it on his plate so that the food would touch each other and then they’d tell him, better not eat it, that it’d poison him. First time I realized that was one time when Millie and Daddy were separated. He came by with Junior just at mealtime, and I set Junior a place not knowing how he was. I just fixed his plate like I did for my kids, and he set up such a yowl. He says, “You hate me! You want me to die!” And I couldn’t figure out what was the matter with him, and he says, “Well the food is touching! That’ll poison me! I’ll die!” And he wouldn’t eat nothing either.

Daddy’s nickname for Millie was “Peaches” because her complexion was so perfect. She never had to wear makeup. She was a very pretty girl, but she got heavy as soon as she got married. Millie never cared too much for women, but she loved me. We were closer than most sisters. When we were neighbors, Millie’d bring Junior over to me every day. She’d get all her housework done up, her house nice and clean, and then she’d bring Junior over to me and go out tomcattin’ and come over and get him just before time to go for Daddy. One time Junior told me—I guess he’d been having a hard time one way or another—“I sure wish you was my mother.” That sure made me proud, I’ll tell you.

Later on Daddy got a job on the tuna fishing boats. One time they were reported lost at sea, and they were gone for forty days. They had got becalmed on the ocean, out there somewhere. Usually they’d be gone for two weeks, come back for a few days, and go out again. And Millie would leave Junior out in the cold, no supervision, nothing to eat. Daddy come home and found that one time. The landlady lived in the front house, and they lived in the back. So, after that, he made arrangements with her that Junior was to come to her house after school. But I don’t think Daddy made many trips after that.

Daddy and Millie fought all the time. They’d have regular knockdown-drag-outs nearly every day. And Junior would get underneath the sink and sit there and scream bloody murder. It’s no wonder he grew up the way he did. He never did have a normal childhood. Only with Grandma, and she wasn’t affectionate enough. And he was Italian, and so, you know, he needed more affection than other people.

Millie and Daddy separated half a dozen times. It was on-again, off-again. She’d leave every whipstitch. Then, when she found the going too rough, why, she’d come back. And Daddy always took her back because, he said, to his way of thinking a child needed its mother. That was a strong point with him, even though he got to the point where he actually disliked her intensely. Still he thought that she would be better for Junior than somebody else.

There was one time when Daddy and Millie separated—I think Junior was only about nine or ten months old. Oh, well, she left him before that. She left him when Junior was only a few months old. She left the baby with Irma, Dick’s wife, and she went home to her aunt (Mrs. Bartold), and the aunt promptly brought her home to Arthur the next day. That’s when all this buisness came out that we had never heard of before. The aunt give Daddy a real dressing down. She told him, “When you married Ida,” that’s what she called her, “When you married Ida you assumed responsibility for her because she was a ward of the court before that. So no matter what she does, she is your responsibility until she’s twenty-one years old.” Daddy knew he was licked.

There was another time that they were separated for nine months, and Daddy and Junior lived with Grandpa Joe and Grandma in Watts. Grandma took care of him then, and that’s when he made the most progress physically. Because he didn’t have this upheaval all the time. He was just a little fellow then. He ate regular and had regular hours, and he was a pretty happy baby. Millie’d come to see him once in a while, but Daddy forbid her to take him anyplace. Then after nine months they got back together again. They finally broke up once and for all when Junior was seven. And that’s when he went to live with his grandmother permanently.

At that time Grandma had a chicken ranch over here in Nuevo. Grandpa Joe had died, and she had her brother helping her out there. She had traded her house for the ranch. Then she couldn’t make the payments on it, so she traded her interest in the ranch for a house on Eighty-third Street in Watts.

Sandy was the man that Millie was going with while Daddy was off fishing, while they were still married. And he didn’t like Junior at all. But she went to live with him after she and Daddy separated for good. She used to tell me all kinds of things: when Daddy’d get paid, he did her like he did me, too, later; he’d give her all the money he brought in. So she was buying up pillows and pillow slips and sheets, towels; she was fixin’ it all together. Then, when she got what she wanted, she told me, she intended to leave Daddy and go with Sandy. And she kept this stuff at my house.

Well, I knew what her plans was, but I think Betty Ward told Daddy ’cause he knew everything she did. Everything. So, one day, here comes Millie in Sandy’s car. She came to get the suitcases with all these towels. And here comes Daddy. Nobody expected him. He looked around until he found the suitcases in my boys’ closet, and he took each one of them towels and just ripped it in half, and they had a knockdown-drag-out fight right in my house. Well, that was the last time they were together. When she got back over to Grandma’s house, she picked up Grandma’s iron and threw it at Daddy and it just missed him. Would have killed him if it didn’t. She went to stay with Sandy after that.

Now, Sandy wanted to marry her. Daddy was in the L.A. County Hospital for an operation on his head, some polyps or something. He was always having to have operations. Then, while Daddy was there, Sandy had a stroke and they took him to the hospital, too, same floor. I met Millie at the elevator, you know, and she told me she was hoping that Daddy would die so she’d get Junior. But Sandy wouldn’t have Junior; he wouldn’t even consider takin’ him. Still, she thought if she married Sandy and Daddy died, she’d get Junior. But Sandy died. That was poetic justice for you, I guess. Sandy died right there in the hospital.

Grandma used to tell me how sorry she felt for Junior. Like one day, she told me she found him just sittin’. She thought he was reading a book, but he was just sittin’ there, not making a sound, and the tears just rolled down his face. She asked him what was the matter, and he said he wished he had a mother and a father and sisters and brothers like other children had.

Junior was just little when he got interested in music. Mr. Parry was his first teacher, and I’m sure Junior remembers him. He was about nine years old, and they were living in Watts, and Mr. Parry recognized immediately that he was very gifted. In fact, when they moved to ’Pedro, Mr. Parry was so impressed with his talent that he made the trip from L.A. every week to teach him.

Grandma was proud of Junior’s talent. Oh my, yes! She’d talk about it, too, to other people. She might not have bragged to him, but to anybody else who would listen she would brag to high heaven about Junior’s talent. Because she knew in her mind that he was going to be very rich and famous when he got grown. Junior kind of took the place of the children she lost. But she never was lovey-dovey, even with her own kids.

He could do no wrong, Junior couldn’t. She’d get out of patience and angry with him sometimes: he liked to aggravate her; he’d bait her—instead of using a spoon, he’d slurp his soup out of the dish. He’d put his head way down. Hahahaha! And Grandma firmly believed that when he grew up he was going to be an outstanding musician, and she used to tell him, “You’re going to be in society. You’re going to be in a position where you’ll need to know manners!” And I remember him making the statement “I’m going to be such a great musician that it won’t make no difference if I have manners or not!”

John and Millie Noble

(John) I can’t say why it took place; I was only six or seven. I just went into their house there on May Avenue in Watts to get Art Junior to play. We were always climbing trees. And here were Moses and Moham [Art Senior and Millie, Art’s mother] going at it hammer and tongs. They were battin’ one another around, calling each other all the names in the book. Art Junior was squalling and a-wailing underneath the sink, and I was afraid to try to run for the front door to get out again, so I just went down on the kitchen floor with him. I was as scared as he was. They were bangin’ one another around. She hit him with a pot or pan; some doggone thing clattered down on the floor. Moses had a very explosive temper, and Moham was like a wildcat; she’d fight anything and kinda kept us kids a little bit away.

We called him Moses, Art Senior. Art Junior made up that name. Him and I talked about it. He said, “He’s as old as Moses and he’s as wise as Moses.” And from that time on it was Moses.

He was a self-educated man, very intelligent in quite a few ways because he educated himself in the field of diesel engineering, and he was a machinist, first-class. He had fantastic tools, and he was very meticulous. His greatest love, of course, was the labor movement. He started in Seattle. It was the IWW, the Wobblies, and he progressed in that field for as many years as he could until they finally kicked him out of Washington State, and he became acquainted with Harry Bridges and became an organizer for him to create the ILWU.

Moses was very one-way about his thinking. He researched what he was interested in and then that’s the way it was in his mind. I learned a lot from him, and I’m quite certain that everyone that was around him did. He was a hard person to forget. You either loved him or you hated him. There was no middle road.

My next vivid thought about Moses was during the ’38 strike, when he had a small Plymouth sedan, and they were going to go out and get some scabs. And they did a good job at that time on those people who were trying to break that strike.

He was about six foot tall, and he was lean, and he had that bad eye, and he had his right thumb cut off, let’s see, by an accident in a machine shop after that ’38 strike. He was there because they were trying to run him off the waterfront. He had to get off the waterfront there for quite a spell.

(Millie) What about that rumor about Pancho Villa?

(John) That wasn’t a rumor. That was a fact. Moses and a friend of his took a boat out from San Pedro, and they were supposed to be going out fishing. Well, this friend—Moses never mentioned his name to me—headed due south when they got out of the harbor, and it wasn’t until they were at sea that Moses learned that they were going to Mexico with a load of firearms for Pancho Villa’s revolution.

There was another occasion in ’29 or ’30 where Moses had to leave the country because of his union activities, and he went to the Philippine Islands and ran a bar in Manila. When he came back, which was after the big depression had already set in and settled across the country, he came back with quite a little bit of money, and he was back commercial fishing again. He made several trips down to South America. I recall he brought back tuna fish, and being as the whole family was there—Grandma and Irma and Dick Pepper and us kids—well, he salted up some tuna in a big barrel and he put too much salt in it and it burnt the tuna up to where we couldn’t eat it. But he tried. He wanted to do it on his own. And he was always out to help anyone. That was one of his big things. Even if he didn’t like you, he’d try to help you. Later in life . . . That probably explains how he was with Moham. My wife could never understand it. We’d go over to their house and here was his wife and his ex-wife sitting knitting on the same couch. The whole family stayed together all these years. That was very important to Moses.

(Millie) Remember that time Moses wanted to buy some property? He was going to have him and Mommy [Thelma] live on the middle of that property. On one corner was going to be Junior and Patti; another corner, Bud [John’s brother] and his wife, Aud; us in this corner. He was going to be . . .

(John) He was going to be the patriarch. He wanted to keep us together so we could always be in contact with one another, but there’s one thing Moses didn’t visualize, I don’t believe, and that was such a fast-moving civilization coming up, going faster than he could think.

Grandma Noble was a very, very—hahahaha!—stubborn and hardheaded woman, but you had to love her. Art lived with her, you see, and was under her domination more or less. Grandma had set ideas, same as Moses did, and when she told Art Junior, “I don’t want you smoking! I don’t want you doing this!” well, she expected to be obeyed, and Art, of course, didn’t obey very easily. She was the same way with me, but I loved her very much because she did so much in trying to help me, although I didn’t agree with the way she went about it. She tried to make me be industrious, clean living. She was a very good woman. Her ideas about young people probably coincided with mine in this modern day and age.

Grandma and Moses fought hammer and tongs verbally, being both as stubborn and hardheaded as they were. They couldn’t come to a meeting of the minds. Grandma didn’t like the way Moses was living with some of the women he went around with. Moses was her son and she thought she had some control over him. Moses wouldn’t conform at all. He paid her bills, made sure everything was there, furniture, food, but he didn’t want her telling him what to do, the same way he wanted to tell other people what to do. It was a conflict constantly, always a friction.

Moses always admired my mom when she was a young woman. He was in love with her for many years before they finally got married. My dad treated my mom very shabbily. And Moses didn’t believe that a man should treat a woman shabbily. He could knock her down and kick her—that’s fine—but he had to feed her and give her the necessities of life. With Shorty, he’d go down and work, longshoring, and leave Momma with no money. He’d spend it all in the bars. He wasn’t like Moses. He wouldn’t take care of the family first and then go drink it up. He’d spend all the money down there and come home broke. We didn’t have food in the house.

Dad left in 1939, ’40, and Mom and Moses got together. He was always quite attracted to her, and he, in her eyes, was a good provider even though he drank and horsed around. He’d been divorced from Moham, oh years and years. In 1942, when I entered the navy, Mom told me he was staying at some hotel in San Francisco, so I went to see him before I shipped out. I woke him up in his hotel room; his gang was workin’ up there. We spent one evening and all night together, and he told me, just before I left, he says, “Well, John, I’m gonna go back and marry your mom.” And I says, “Well, that’s okay with me, Moses. I hope you have a lot of fun.”

They started living together, and by the time I came back from the service, Momma could legally get married again. By that time, Moses was in his fifties, and he always treated my mom like a queen because he saw what my dad had done to her and to me, beat me up, threw me out. Moses loved kids, and the old man would beat the poop out of my brother Bud and I. Moses couldn’t stand to see children mistreated, beat, and without food. And he brought us food, gosh yes! Moses’d come to the house and bring us food and sometimes clothing because my old man would feed us· all canned tomatoes and then he’d tell my mom, “Cook me up a steak.”

When we were in grammar school, Bud and I used to go over to where Art lived with Grandma and build little wooden stick airplanes and play on the floor or outside. We flew kites together. Now, everybody called him Junior, and he didn’t like it, and I didn’t blame him. I always called him Art. And when the other kids wanted to fight or beat him up, he was always protective of his mouth because even when he was a small kid he was playing the horn. Mr. Parry, his teacher, was always warning him about hurting his mouth; he said that was his livelihood to come. So I’d get into arguments with Art, but I never fought with him like Billy Pepper did, and Bud. I’d intercede on the few occasions I was around when it happened, and Art always respected me for that. I think that was more or less the bond between us.

I used to go over, to go swimming or something with Art, and I’d have to wait while he finished his lessons. Art was excited about his music to the extent that when I came over he’d show me a music lesson or passage that Mr. Parry had left him and he’d say, “How does this sound, John?” He’d play it for me. I didn’t know one note from another, but I listened and I could see just how enthusiastic he was. The last time I saw Mr. Parry and Art practicing in the living room there, Mr. Parry said, “Art, you keep this up and your name will be in lights all over this whole country.” Of course, Art was a little puffed up about that.

We used to talk. I had my mom, who showed a lot of love and protection for us kids; whereas Art, his mother was not there and he had to depend on Grandma and her strictness and Moses and his very vocal—he was very forceful in the way he spoke, especially when he was a young man. Art used to love to get away; we spent a lot of time together just because of that. And he’d often say, “I wish I could just get away from Grandma, from Moses.” He talked very little about Moham. Very little. Because, you see, she was too young then to be very maternal toward him. She went her way and let Art Junior go his, and he resented that very much. But he liked my mom real well. Momma was always loving toward him and she petted him, which he didn’t have because Grandma Noble wasn’t a loving type of person in that respect except to me. She never expressed any affection or love for Art when he was a little boy.

When we got older, we did a lot of drinkin’, both of us. We’d go to a drugstore; they didn’t demand your identity. We’d buy a pint of Four Roses, take our girls out on a date, and we’d drink it up. Usually, I went back to Grandma’s house with Art and slept in the same bedroom there, and we’d get up in the morning and drink up all Grandma’s milk outta the icebox because we both had hangovers. We’d guzzle it down. And then we’d go to the beach, Cabrillo Beach. We’d mostly finagle some beer to drink down there. We’d swim, sit out on the rocks.

After the war, and just before the war started, Art took me out on some of his jam sessions that he’d go to on Central Avenue. He’d take me to these clubs, and they were mostly black people that he associated with very closely. They were fine musicians, and they accepted him when he’d come in there because he was that good.

One night Art was playing, and they had this dancer, a mulatto girl—we were drinkin’ it up. She came around and danced on these tables, slipped off her garter, threw it up in the air, and I caught it. She said, “You’re the one!” I didn’t know what to do. I was too young. She got down off the table, stretched the garter out, and put it around my neck. She says, “You have to kiss your way out of that.” I was thrilled to pieces, but here were all these people looking on. Especially all these black people. Art was still up there jammin’. I told him about it when he came back to the table, and he says, “Well, you missed your big chance.” Oh, lordy! That was before the war. Now, I left in ’42 and I didn’t see Art again until ’46.

* See Cast of Characters on page x, for identification of speakers.