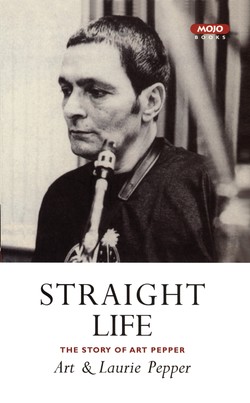

Читать книгу Straight Life: The Story Of Art Pepper - Art Pepper - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление| 6 | On the Road with Stan Kenton’s Band1946–1952 |

AFTER I SNIFFED IT that morning in Chicago, I bought up a whole bunch of heroin, got a sackful of caps. We traveled back to Los Angeles. I guess it took us three months to get back, playing all the stops in between, and at this time we had a little vacation from Stan, about a month before we had to go out again. I told Patti I had sniffed a little bit, but it was okay, it was alright. She felt bad but she went along with it. Then I ran out. I got totally depressed and my stomach hurt. My nose hurt something awful, terrible headaches; my nose started bleeding. I was getting chills. I was vomiting. And the joints in my legs hurt.

I had to go to a session so I got hold of some codeine pills and some sleeping pills and some bennies, and I got a bottle of cough syrup and drank it, and I went out to this session because I still couldn’t believe I was that sick.

Everything was real clear to me. Everything was so vivid. I felt that I was seeing life for the first time. Before, the world had been clouded; now, it was like being in the desert and looking at the sky and seeing the stars after living in the city all your life. That’s the way everything looked, naked, violently naked and exposed. That’s the way my body felt, my nerves, my mind. There was no buffer, and it was unbearable. I thought, ‘Oh my God, what am I going to do?”

I looked around the club and saw this guy there, Blinky, that I knew. He was a short, squat guy with a square face, blue eyes; he squinted all the time; when he walked he bounced; and he was always going ‘Tchk! Tchk!”—moving his head in jerky little motions like he was playing the drums. Sometimes when he walked he even looked like a drum set: you could see the sock cymbal bouncing up and down and the foot pedal going and the cymbals shaking and his eyes would be moving. But it wasn’t his eyes; it was that his whole body kind of blinked. He’d been a friend of mine for years and I knew he goofed around occasionally with horse, heroin, so I started talking. I said, “Man, I really feel bad. I started sniffing stuff on the road and I ran out.” I described to him a little bit of how I felt and he said, “Ohhhh, man!” I said, “How long is this going to last?” He said, “You’ll feel like this for three days; it’ll get worse. And then the mental part will come on after the physical leaves and you’ll be suffering for over a week, unbearable agony.” I said, “Do you know any place where I can get anything?” He said, “Yeah, but it’s a long ways away. We have to go to Compton.” We were in Glendale. At that time they didn’t have the freeway system; it was a long drive but I said, “Let’s go.” We drove out to Sid’s house.

As we drove I thought, “God almighty, this is it. This is what I was afraid of.” And the thought of getting some more stuff so I wouldn’t feel that way anymore seemed so good to me I got scared that something would happen before we got there, that we’d have a wreck. So I started driving super cautious, but the more cautious I was the harder it seemed to be to control the car. The sounds of the car hurt me. I could feel the pain it must be feeling in the grinding of the gears and the wheels turning and the sound of the motor and the brakes. But I drove, and we made it, and we went inside, and I was shaking all over, quivering, thinking how great it would be to get something so I wouldn’t feel the way I felt.

Sid was a drummer also, not a very good drummer, but he had a good feeling for time. He was a guy I’d known a long time, too, a southern type cat with a little twang of an accent. We went in and Blinky told Sid I’d started goofing around and Sid said, “Ohhhh, boy! Join the club!” He said, “What do you want?” I said, “I don’t know. I just want some so I won’t be sick.” He said, “Where do you fix at?” I said, “I don’t fix. I just sniff it, you know, horn it.” He said, “Oh, man, I haven’t got enough for that!” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “If you want to shoot some, great, but I’m not going to waste it. I don’t have that much.” I said, “Oh, man, you’ve got to, this is horrible. You’ve got to let me have something!” He said, “No, I won’t do it. It’s wasted by sniffing it. It takes twice as much, three times as much. If you’d shoot it you could take just a little bit and keep straight.” I said, “I don’t want to shoot it. I know if I shoot it I’m lost.” And he said, “You’re lost anyway man.” I begged him and begged him. I couldn’t possibly leave that place feeling as sick as I did. I couldn’t drive. I couldn’t do anything. I didn’t care what happened afterwards, I just had to have a taste. Finally I said, “Okay, I’ll shoot it.” He said, “Great.”

They both fixed, and I had to wait. At last he asked me what I wanted. I asked him how they sold it. He said they sold it in grams: a gram was ten number-five caps for twenty dollars. I said to give me a gram and he said, “Whatever you want.” I said, “I thought you only had just a little bit.” He said, “I only have a little bit but I got enough.” It was just the idea that he wanted me to fix. I knew that. So I’d be in the same misery as he was. He said, “Where do you want to go?” I looked around my arms. I didn’t want to go the mainline, the vein at the crook inside your arm, because that’s where the police always looked, I’d heard, for marks. I asked him if he could hit me in the spot between the elbow and the wrist, the forearm.

Sid put a cap or a cap and a half of powder into the spoon. He had an eyedropper with a rubber bulb on it, but he had taken thread and wrapped it around the bulb so it would fit tight around the glass part. He had a dollar bill. Here came the dollar bill again, but this time instead of rolling it up as a funnel he tore a teeny strip off the end of it and wrapped it around the small end of the dropper so the spike would fit over it real tight. That was the “jeep.” He put about ten drops of water on top of the powdered stuff in the spoon and took a match and put it under the spoon. I saw the powder start to fade; it cooked up. He took a little bit of cotton that he had and rolled it in a ball and dropped it in the spoon, and then he put the spoon on the table. He took the spike off the end of the dropper and squeezed the bulb, pressed the eyedropper against the cotton and let the bulb loose. When he had all the liquid in the dropper he put the spike back on the end of it and made sure it was all secure. Blinky tied me up. He took a tie he’d been wearing and wrapped it around my arm just below the elbow. He held it tight and told me to make a fist. I squeezed so the veins stood out. Sid placed the point of the needle against my vein. He tapped it until it went in and then a little drop of blood came up from the spike into the dropper and he told Blinky to leave the tie loose and me to quit making a fist and he squeezed the bulb and the stuff went into my vein. He pulled the spike out and told me to put my finger over the hole because blood had started to drip out. I waited for about a minute or a minute and a half and then I felt the warmth—a beautiful glow came over my body and the stark reality, the nakedness, this brilliance that was so unbearable was buffered, and everything became soft. The bile stopped coming up from my stomach. My muscles and my nerves became warm. I’ve never felt like that again. I’ve approached it. I’ve never felt any better than that ever in my life. I looked at Blinky and at Sid and I said, ‘O h boy, there’s nothing like it. This is it. This is the end. It’s all over: I’m finished.” But, I said, “Well, at least I’m going to enjoy the ride.”

After I left the house I went to a drugstore that Blinky knew. At that time you could buy spikes easy, so I got four number-twenty-six, half-inch hypodermic needles, an eyedropper that had a good, strong bulb on it, and went home. I had about nine capsules of heroin left. I walked into the house and Patti met me at the door. I went into the kitchen. I put this stuff out on the table, and she looked at it, and she said, “Oh no!” I said, “Yeah, this is it. You’ll have to accept it.” I got a dollar bill and tore a little piece off the bottom to make the jeep. I got a glass out of the cupboard, a plastic one so it wouldn’t hurt the end of the needle when I put it in to wash it out. I took a cap and put it in the spoon and put some water in it, and all this time I’m talking to Patti, trying to explain because I loved her and I wanted her to accept this. I got a tie out of the closet and asked her if she would tie me, and she wrapped it and held it and she was trying to be cool and be brave, and I stuck the thing in, and the blood popped up, and I told her, “Leave it go. Leave it go.” I looked up, and I’ll never forget the look on her face. She was transfixed by the sight of the blood, my own blood, drawn up, running into an eyedropper that I was going to shoot into my vein. It seemed so depraved to her. How could anybody do anything like that? How could anybody love her and need to do anything like that? She started crying. I took her hand away and took the tie off. I shot the stuff in, and when I finished I looked at her. She turned her head and cried hysterically. I put my arms around her and tried to tell her that everything was alright, that it was better than the drinking and the misery I’d gone through before, but I couldn’t get through to her.

After I got the outfit and started fixing, that was my thing. I still drank and smoked pot, but I was a lot cooler. Things were going great for me. I was featured with the band and we played all over the country. We’d go from one state to another and the bus driver we had at the time was a beautiful cat who knew what all the liquor laws were—some states were dry—and he’d stop just before we crossed into a dry state and say, ‘This is the last time you can buy alcohol until such and such a date.” We’d all run out of the bus. We’d figure out how much liquor we’d need. If we went to Canada and had to pass through an inspection station we’d take our dope, the guys that were using heroin, our outfits or pills, and give them to the bus driver to stash behind a panel. We’d go through the station and get shook down, and then he’d open the panel and give us our dope back. And wherever we’d pass through we’d buy different pot. In Colorado we’d get Light Green and in New Orleans it was Gunje or Mota. There were a lot of connoisseurs of pot who’d carry little film cans of it and pipes with screens to filter it, and when we had a rest stop we’d jump out of the bus and smoke.

Me and Andy Angelo roomed together for a long time and before that it was me and Sammy, and we each had our outfits. I had a little carrying case, like an electric razor case. I had an extra eyedropper and my needles, four or five of them. I had my little wires to clean the spike out in case it got clogged. I had a little bottle of alcohol and a sterling silver spoon that was just beautiful and a knife to scoop the stuff onto the spoon. I used to carry this case in the inside pocket of my suit, just like you’d carry your cigarettes or your wallet. I even carried a little plastic glass. I would set up my outfit next to the bed in the hotel with my stuff in a condom—we used to carry our heroin in one to keep it from getting wet. I’d wake up in the morning and reach over, get my little knife, put a few knifefuls in the spoon, cook it up and fix. It was beautiful.

It was wonderful being on the road with that band. Everyone liked each other and we all hung out together. When the bus left Hollywood we’d buy bottles of liquor and start drinking; that was just standard procedure: it was a celebration. I always prided myself on being able to stay up longer than anybody else, drink more than anybody else, take more pills, shoot more stuff, or whatever. I remember once when we left L.A. we kept drinking and drinking and smoking pot and having a ball until the bus just ceased to be a bus. We wandered up and down the aisle talking and bullshitting. We kept going and going until, after about twenty hours, everybody started falling out. When it got to thirty-six hours only a few of us were still awake, and finally there was nobody left but me and June Christy. She could really drink. I don’t remember how many quarts we put away. We drank continuously, I guess, for a good forty-six hours and we were going to keep it up until we got where we were going, but she fell out, too, so there I was all alone. That was awful and I panicked. I couldn’t stand for anything to stop once it had begun; I wanted it to continue forever. I went up and started talking to the bus driver, and I stayed awake the whole time.

We hardly ever flew to a job, but a couple of times we had to when it was too far and we couldn’t possibly make it in time. Once we flew to Iowa and rented a bus and the bus broke down when we were out on a little, two-lane highway. The weather was bad, like it is in the midwest, alternately raining and snowing, and ordinarily we would have been drug, but we were all in such a happy frame of mind we just played right over it. We were goofing around, and we had a habit, like, in the bus, we would blow sometimes. Andy and I would sit together and scat-sing. We’d sing the first chorus of a song together, bebop, and then blow choruses, trade fours, and do backgrounds. Sometimes other people would join in and we’d really get into it and take out our horns, the ones you could reach easily in the bus. I’d get my clarinet and play some dixieland; maybe June would sing and we’d play behind her. So, as it happened, we’d all been drinking and were having one of these little sessions when the bus broke down.

Our regular driver was back with our regular bus trying to get it ready, and this driver we’d just hired didn’t know what to make of us. He was fascinated. He made an announcement. He was going to radio ahead for help. We said okay and kept on playing, and all of a sudden we just found ourselves marching out the door of the bus. It was freezing cold but we had our coats on and our mufflers, and before we knew it there were twenty guys out there, with horns, marching down the highway. There were farms and stuff, you can imagine, cows and dogs and things. We’re going down the highway playing marches.

June Christy was a pom-pom girl strutting down the road. She was a cute little thing with light hair and a little, upturned nose. She had a lot of warmth and she was sexy in that way, no standout shape, but she was nice and everybody liked her, and she had crinkly marks around her eyes from smiling a lot. Her husband was Bob Cooper, who played tenor with the band. He was very tall with blonde hair and the same crinkly thing around his eyes. People used to wonder why she had married him, being June Christy. People thought that she and Stan might get something going, and there were a lot of guys that dug her, but she married Bob, and I understood it. He was one of the warmest, most polite, pleasantest people. He was completely good if you can imagine such a thing, just a sweetheart, and he got embarrassed easily, and he blushed a lot. And he used to drink with June; he would look after her; they were a great pair. And they were marching down the road.

Ray Wetzel was marching, a fat funnyman, always laughing and smiling. He had a lot of jokes and little comic routines he used to do, and he was a wonderful trumpet player with a beautiful sound. Shelly Manne was out there in a big Russian overcoat with a fur collar and a big babushka or whatever you call it on his head. Shelly’s like the picture “What Me Worry?”, and he’s always making jokes, and he doesn’t drink, and he doesn’t smoke pot: he’s naturally high. He’s playing the snare drum, playing wild beats and walking like he’s crippled. Bart Varsalona joined in playing his bass trombone, another comedian.

Bart was a sex freak, and he had an enormous joint, one of the biggest I’ve ever seen. Occasionally on the road he’d invite some of the guys down to his room, where he’d have some real tall showgirl-hustler. He’d haul out his joint and slam it on the table top, and then he’d have the chick do a backbend or something and give her head while we smoked pot and drank and watched. A lot of the guys in the band considered themselves real cocksmen, but I’ll have to admit that the kings—for pure downright sex and the number of freaks they knew in each town—were Bart and the bass player, Eddie Safranski. And Eddie was there, too, on the highway.

Al Porcino was up in front, a marvelous trumpet player, a nice-looking guy about six feet tall. In his room sometimes he’d take Ray Wetzel’s pants and put them on, the pants from his uniform. He’d fill himself up with pillows and dance in front of the mirror. A couple of times he even went out on the stand like that. He always wanted to be a band leader. He had a book full or arrangements, and wherever he went, all his life, he’d get guys together and rehearse them like a big band. So he was out there with June, leading us, twirling his trumpet like a baton, marching backwards and shouting out commands, and we were doing all these movements, and we were all drunk and running into each other.

Bud Shank was marching, playing his flute, playing all those trills like they do, and Milt Bernhart—he had a big moustache at the time—he looked like Jerry Colonna. He was the lead trombone player and nobody could play louder than him. He had the most fantastic chops of anybody I ever heard. He was playing his slide trombone and walking, pointing it up in the air and going “Rrrr rruuuhh uhhh!” And we went into “When the Saints Go Marching In,” and we were just shouting. And we really believed that we were marching in the Rose Parade or something. Cars and trucks were coming, and it was so far-out for this to be happening in that spot that they pulled off the road to watch, and they had cameras and kids and dogs, and they had the whole place bottled up, and the highway patrol finally came and made us get back in the bus. We were blocking the road. That was one of the great times. We had some great times.

STAN TURNS MINNEAPOLIS ‘INNOVATIONS’ INTO MUSIC APPRECIATION SESSION by Leigh Kamman

Minneapolis—Stan Kenton blew into Minneapolis in March with a North Dakota blizzard, and the storm converted his first concert into a music appreciation session. With two concerts planned, at 7:30 and 9:30 p.m., and only several hundred spectators there for the first concert, Stan decided to combine the two at 9:30.

In appealing to the audience Kenton said, “Thank you very much for climbing through the storm. We appreciate very much you all being here.

“I wonder if we might ask a favor? So that everyone may enjoy or reject what our music offers, we would like very much to combine the two performances into one.

Meet the Band “Meanwhile, we would like very much to have you meet the band . . . get acquainted with violins, cellos, violas, brass, reeds. If you want to know something about drums, see Shelly Manne. If you have questions about vocal music, see June Christy. In fact, we invite you to come on stage. If you can’t get up here, we’ll come down there.”

Forty musicians and several hundred spectators swarmed on stage and through the audience. Shelly Manne demonstrated percussion. Maynard Ferguson spoke for the brass section. June Christy talked to aspiring young singers. And the local musicians checked their ideas against those of the big band musician. The local cats and fans did some genuine worshipping while the Kenton crew did some genuine responding with answers and autographs.

Session In spite of storm and a serious air crash within the city limits, the crowd grew as 9:30 approached. At 9, Art Pepper, Bob Cooper, Buddy Childers, Don Bagley, Bud Shank, and Milton Bernhart played a jam session.

The crowd gathered in front of the stand while the Kenton men honked. By 9:30, some 1,200 persons had plodded through wind and snow to Central high auditorium. And at 9:45, the concert got underway with everyone happy and receptive for “Innovations.” down beat, April 21, 1950. Copyright 1950 by down beat. Reprinted by special permission.

(Lee Young) I always liked Stan Kenton. A beautiful person. As a matter of fact, I think he used to be rehearsal pianist at the Florentine Gardens on Hollywood Boulevard. The first time I met Stan, I met him with some disc jockey. Stan’s one of the warmest people you would ever meet. He’s just an elegant man. I’m talking about years ago; when you meet him now, the man’s just the same. The man’s the same. So you wonder, they must have thrown the pattern away. When you see what goes on today with people, you wonder how . . . Seems like all the wonderful, compassionate people were born a few years ago. Seems that way.

Bob Cooper and June Christy

(Coop) We were all very young when we got together with Stan, and he was like a father to us. He worried about people’s problems and tried to resolve them when he could, so we had a high regard for him. And, of course, Stan had people across the country that worshiped him, idolized him, and that was part of the magnetism of the band, Stan’s personal magnetism.

(Christy) I’ve often said that if Stan wanted to run for president, it would be a landslide because he had that powerful personality, that ability to win people over. No one’s perfect, but he was great to his people, and we were his children, and we were all protected. I think you’ll find very few people who’ll say anything negative about him. I can’t really think of anything.

(Coop) We always thought we should make more money.

(Christy) That’s true.

(Coop) That’s about the only thing.

I joined the band in 1945. The band Art joined—that was probably my favorite of Stan’s bands. Art was there and Bud Shank, and I was getting to play more solos than before because the band was getting into a younger trend of music that we enjoyed. Shorty Rogers started writing some arrangements, Gene Roland, the more swinging things. I think all the jazz soloists in the band enjoyed it much more than Stan did. He still liked the flashy type of arrangement. And I never felt that Stan really knew when the band was swinging its best. We would wait for the moment when he got off the stand to go check the box office or something, and then we’d call all the music that we liked to play.

(Christy) The audience reaction to that band was usually great, but it depended upon where we played. If we played for an audience who expected to listen to the band and not dance, they were avid fans, and they wouldn’t budge a muscle. They’d just listen with their eyes wide open and their ears wide open, but, as we often did, sometimes we’d be booked into a dance palace, and people looked at us as if we were freaks because there was nothing to dance to and the band was always loud. So, if you weren’t a Kenton fan, the band wasn’t that popular. For the most part we played for Kenton fans.

Traveling was no joy, but we were so young, and I, for one, was so thrilled at being with the band because that had been my ambition ever since I can remember. I started singing when I was about thirteen in my hometown, and I had to be a girl singer with a band. I would have settled for any band, but Stan, who was at his very hottest at that moment! I was in seventh heaven.

I had promised my mother I would finish high school before going to the big town, Chicago. And I did. I was all packed the night before graduation. Packed! I had two dresses and one pair of shoes.

It was a fluke thing that I got the job with Stan in the first place. I’d heard that Anita [O’Day] had left the band and I figured that this would sure be an opportunity. I’d heard that the band was coming to Chicago. I thought at the time (I was totally wrong) the first place they’ll go is the office that books them. Stan hates those offices as much as I do. But in this case I guess he needed a singer, and he needed one fast. The first hit record the band really had was Anita’s, “Her Tears Flowed Like Wine.” I don’t think Stan ever cared for singers really, but at that time he felt he needed one. I was sitting in the reception room. I would have sat there all day long on the assumption he would be there, and he finally came in. I gave him my little test record. He played it and said, “I’ll let you know in a couple of days.” I never suffered so much as I did during those two days waiting to hear from him. He finally called and said, “Well, we’ll try you out for a few weeks and see what happens.” Years later—we used to do all those disc jockey shows because they were important in those days—we were coming back from one of those things and I said, “Stan, you never did tell me, am I permanent?” I’d been with the band for about eight years! “Tampico” was my first record and it was, I think, one of the biggest hits the band ever had. I got paid scale for it. I’d been with the band for only a few months when we recorded it. I hated that song.

We used to joke about ‘The Bus Band in the Sky” because we never seemed to get off the bus. There were a lot of times we didn’t have the time to check into a hotel and we’d have to do the gig and then get back to the bus and go to the next job. And particularly for a girl it was not too much fun because I think a woman has a little more to worry about, to look good, to get her hair done.

(Coop) But you were the envy of most of the girl singers around at that time. The band was very popular, and singing jazz .. . To quote the late Irene Krai, she said that when she was in high school she could hardly wait for the band with June to get to town so she could watch June and hear her sing: “That was the hippest shit in town.”

(Christy) That was one of the nicest compliments I’ve ever received.

(Coop) Of course, the itineraries, they just went month after month, sometimes with no days, no nights off. And if we did get a night off, it might be traveling on the bus all night long. After a few years it got very tiring. Especially after we got married. Then it was even more of a chore because we were looking forward to settling down and having a home and so forth. It was tough, no doubt about it.

(Christy) And if we hadn’t liked what we did so much, there was no way we could have done it.

(Coop) The particular bus I enjoyed the most was the first Innovations tour. We had two buses.

(Christy) That was when we had the strings and so on. Stan was really out to prove something.

(Coop) Our driver was Lee Bowman, and we had such a good time on his bus, at the end of the tour we bought him a watch for tolerating our drinking and stopping in the middle of the night to go into a bar and get more beer or whatever. It was called “The Balling Bus.”

(Christy) And the other bus was called ‘The Intellectual Bus.” And we, as a matter of fact, were quite sure that we were far more intellectual than they, or else why would we be on the right bus?

Whoever booked that particular tour was out of his mind, though, because he should have realized that you can’t get that many people into a hotel all at once. We usually arrived all at the same time, and people got very mean and fiendish. We have a picture of some of the guys actually leaping over the registration desk in order to get there first so they could get to their rooms first. I learned a great lesson from that. I used to just sit in a corner because I figured I was a little too short to fight all of them. I did a tour a while after that with the Ted Heath band, and that tour was a rough one also, but when the bus stopped at the hotel the gentlemen of the band stood by and said, ‘Oh, Miss Christy, you must go first.” That’s when I first learned that it’s awfully nice to be a lady and to be treated like a lady. I don’t mean to imply that the guys in the Kenton band were not nice to me, because they certainly were, and by the same token I respected their privacy. If I felt that it was dirty joke time or something like that, I would go and stand by the bus driver and allow them to have whatever privacy you can have on a bus.

To tell you the truth, the band was kinda, like, clannish. That’s the best word I can come up with, and I think Art was a little reluctant to join the clans for some reason or other. I think he was a bit withdrawn. Art was—I haven’t seen him for so long, that’s the reason I’m saying “was”—he was a very attractive young man, and I’m sure everyone else felt the same way. Art was a very good-looking guy, but some of his illness began to show up at certain times. And, as we all know, when you’re ill, you don’t look quite as good. It didn’t show too much in his playing, but it did in his attitude. He became even more withdrawn.

I think Art is one of the greatest jazz musicians alive today. I say that because I believe it. I haven’t heard him play for a long time. I haven’t seen him. But with the Kenton band . . . My experiences listening to him . . . I honestly feel that way about him. Art didn’t have a chance to be exposed with the band as much as he might have been, which is a tendency of Stan’s. He likes the full, big-band sound, and he’s reluctant, really, to let anyone be the star, so to speak. The musicians appreciated Art’s abilities, but he wasn’t featured with the band that much. Maynard was, and of course Vido Musso. I’ve never been able to figure that out. It’s perhaps because I’m married to one of the finest saxes that there is and I always felt that Coop should be featured as much or more than Vido.

(Coop) I always felt that Art’s major influence was Lester Young; that came out more clearly when I heard him play tenor a few times. Maybe not so much now as in his early days. And to transfer that beautiful sound to the alto! He was really the only one doing that at the time, and I think his sound was by far the best alto sound at the time. Since then there have been other marvelous alto players, but I think that perhaps Art was a major influence in their sound. I always enjoyed his solos; naturally, one of the highlights of the band was Art’s solos. And I still think that the solo piece Shorty Rogers wrote for Art is one of Stan’s best records. It’s a lovely record. It’ll probably last for all time.

(Sammy Curtis) The Innovations band was great. It was one of Stan’s bold moves in music. It was a very aggressive thing he did. He added a big string section and French horns, and the band had a physical structure kind of like a symphony orchestra. At that time no one was thinking in those terms. The band was playing great music, and there was a very brotherly feeling among the musicians. We felt we were participating in something very important. There were a lot of string players who weren’t, you know, “us” jazz guys, and they loved it. They felt it was important to them to be part of it, too.

Stan was a very devoted musician. The orchestra, it was so big, a lot bigger than other bands; they had to build special risers to set the band up on and carry all this equipment on the road. I could be wrong, but I’ve been told by a lot of people that would have to know that Stan was financing the thing out of his own pocket, which, the final line in that story is, he lost a lot of money. But that’s the kind of guy he was. He believed in it so much, he put himself into it physically, spiritually, just to the hilt, and that’s where he was coming from. He was beautiful.

Art was . . . His music was number one to him. That’s all he talked about. We were very close. We’d go and hang out after work, go blow in clubs. Art had a lot of solos in the band; he was featured on a lot of things, and if he’d had a really good night playing, he felt great, but some nights he felt he could have done better, and he’d just get depressed. What he did in his music kind of dominated the way he looked at the whole world.

Art was and is a great player. I’m not going to say the greatest in the world because I don’t feel any one guy is. But at the top of the gang is a select group of five or ten, just a few guys. When you get up that high on the ladder, you can’t pick one as better than the other. That’s where I place Art. He’s one of those special guys. As to what made his playing so special, that’s a hard question, and the only way I can answer it, to be honest with you, I think it’s a gift of God. I think it’s not something that Art did. God loved him and gave him this gift.

If you were Art’s friend, he loved you. He would, I feel, have done anything I asked. Not that I asked anything special, but I felt that kind of brotherly thing. And he respected my work in music, and that was a part of it. You know, I may sound like I’m trying to make something special out of myself because I was not that nice a .. . I wasn’t walking with the Lord then and I was a different kind of guy.

There were a lot of Monday night sessions around town in L.A., and guys’d just drive around in cars and go to clubs and sit in. Art would call me up and say, “Hey, you want to meet me, and we’ll go sit in at this club, and then, if there’s time, we’ll go to another one?” It was just fun to hang out. Chet Baker would come and Jack Montrose, at that time; Jack Sheldon was one of the guys; Shorty Rogers, Hersh Hamel. We’d fill the whole car up and drive to a club.

Something that sticks in my mind—it shows a part of Art’s personality, how very sensitive he is. On Kenton’s band, we were playing at a place in Dallas, Texas. It was a funny kind of setup. It was an outdoors nightclub, all tables, but in Texas there was some kind of law that you couldn’t sell liquor over the bar, so everyone came with bottles and bottles of booze and instead of buying liquor they’d buy soft drinks for mixing. I don’t know why, but the bus brought us there early by mistake, and all the people got there early also, and they just loved the musicians and it turned into a thing, like, “Hey, you don’t have to work yet. Sit down and have a drink.” Well, before the job started, I mean, including yours truly, just about the whole band was juiced out. Stan got there, and we started playing, and everything’s fine, under control, but by the last set, I mean the whole band was just wasted, and Stan was counting the band off, and some of the guys would interrupt him counting off. It turned into one of those things. It was kinda humorous, but Stan was kinda stern and resentful of all this. He could have gotten angry at me or at anyone on the band, but for some reason he picked on Al Porcino and Art and told ’em to get off the bandstand. He kicked them off the stand. I was rooming with Art; that’s how I remember. We had the next two or three days off, and Art didn’t show up at the hotel for two days. I got worried about him. Al Porcino, the next day, he didn’t remember anything that had gone on. But when Art finally showed up and I got talking to him, he said that when Stan did that, kicked him off the bandstand, it really hurt his feelings and he just kinda wanted to be by himself and had drifted around town there. But it’s always stuck in my mind. He was just having fun, and then this incident occurred that hurt him very badly, and when he did show up the poor guy was totally depressed. It happened a few days ago! The other guy doesn’t even remember it; it went in one ear and out the other. Art just hung on to it.

(Shelly Manne) I think it’s important to find Art’s position as a jazz alto player in the history of the saxophone. I think he has a very important part to play because of his distinctive way of playing. He’s very individual. You can hear it. You know it. Art was a very lyrical player. Especially at a time when most of the alto players were in a Charlie Parker bag, Art had a distinct style of his own, very melodic.

Art was a big influence on a lot of people. He had quite an influence on Bud Shank because Bud was very young when he joined the Kenton band and, of course, Art was third alto, the jazz alto chair. In fact, when I settled down out here, finally left Stan and made the first album for Contemporary Records, West Coast Jazz, something like that, I was going to use Art; he was supposed to do the date but for some reason he couldn’t make it, so I used Bud. And that was the first jazz record with a small group on a prominent jazz label that Bud had done; it helped establish his career—a tune called “Afrodesia” that Shorty Rogers wrote with Art in mind.

Art was always a quiet, introverted, sort of one-on-one person. He was never strongly outgoing, but he was always loose with the guys, fun to be around. He’d join in with the groups, with the guys, and he’d go anyplace to play. He wanted to play constantly. So even though we weren’t close socially, we were close musically. I know that. And that kind of business that happens between musicians, musically, is a very strong tie.

We were all happy when Art joined the band because he was really a true, dyed-in-the-wool jazz player, and Stan needed that kind of thing in the band. We had plenty of strong ensemble players, and Art gave it another dimension as far as giving a jazz feeling to the band.

Stan Kenton was great. He was a father confessor to the guys. You could always go to Stan. And Stan’s answer was the word of God, the final word, and you were confident that he’d steer you right. He took a personal interest in everybody in the band, and everybody that worked for him was devoted to him whether they agreed with him in his social life, his political thinking. I always felt Stan was to the right politically, and I was on the liberal end, and we always argued about things politically, but it never interfered with our friendship.

There are a lot of leaders if they get too close to the band they lose the respect of the musicians. Leaders will travel in a different car, stay in another hotel, and just see the band when they get on the bandstand. Stan usually had to go ahead and do interviews or set up; he had his own car on the road but he was with us most of the time. And you never felt aloofness from him. You could say anything you wanted to Stan. And it showed in the music. I think one of the main reasons Stan’s band was such a great success, as was Duke Ellington’s band—which was, of course, the greatest jazz band of all—was that, like Duke, Stan wrote for the individuals in the band instead of writing charts just with an anonymous band in mind and having the musicians play it. He knew our creative abilities; he knew what we could add to the band; and he knew we didn’t want to just take it off the paper and play it. We gave something of ourselves to the music. In Art’s case, Stan used Art, his individual talent, when he’d write charts with him in mind. The band had a very individually creative sound.

It’s always hard doing one-nighters. You look back now, there are some good memories. For some it’s good memories. Everybody has a different kind of constitution, a different ability to take a beating on the road. You travel three hundred miles a night every night on a bus, and in those days you’d have to make a 9:30 in the morning show, something like that, so it was difficult at best. You’d get into town and the rooms wouldn’t be made up, so you spent four hours sleeping in the lobby waiting for checkout. It’s hard, but I think there’s a frame of mind that makes that all part of growing up and maturing and part of enjoying life.

Those are the experiences that later on, difficult as they were, you look back on with a lot of joy because, you know, you try new restaurants, see new places, meet new people, play for new people all the time, which is, in itself, an inspiration. But some guys, now—I’m not sure, I’m just taking a wild guess here—some guys weren’t made up physically for that kind of life and I think Art maybe was one of those guys. I think Art had great difficulty coping with all the temptations of the road.

PROFILING THE PLAYERS

. . .

ART PEPPER, alto sax: He’s 25, says his ambition is to be the best jazzman in America. Art joined Kenton prior to going into service in 1942. Has played with Vido Musso, Benny Carter, etc., and considers Al Cohn his favorite musician. Dislikes the road and the fact that “real great musicians can’t make it unless they smile prettily and talk with gusto.” down beat, April 20, 1951. Copyright 1951 by down beat. Reprinted by special permission.

. . .

THERE’S a thing about empathy between musicians. The great bands were the ones in which the majority of the people were good people, morally good people; I call them real people—in jail they call them regulars. Bands that are made up of more good people than bad, those are the great bands. Those are the bands like Basie’s was at one time and Kenton’s and Woody Herman’s and Duke Ellington’s were at a couple of different times.

There’s so many facets to playing music. In the beginning you learn the fundamentals of whatever instrument you might play: you learn the scales and how to get a tone. But once you become proficient mechanically, so you can be a jazz musician, then a lot of other things enter into it. Then it becomes a way of life, and how you relate musically is really involved.

The selfish or shallow person might be a great musician technically, but he’ll be so involved with himself that his playing will lack warmth, intensity, beauty and won’t be deeply felt by the listener. He’ll arbitrarily play the first solo every time. If he’s backing a singer he’ll play anything he wants or he’ll be practicing scales. A person that lets the other guy take the first solo, and when he plays behind a soloist plays only to enhance him, that’s the guy that will care about his wife and children and will be courteous in his everyday contact with people.

Miles Davis is basically a good person and that’s why his playing is so beautiful and pure. This is my own thinking and the older I get the more I believe I’m correct in my views. Miles is a master of the understatement and he’s got an uncanny knack for finding the right note or the right phrase. He’s tried to give an appearance of being something he’s not. I’ve heard he’s broken a television set when he didn’t like something that was said on TV, that he’s burnt connections, been really a bastard with women, and come on as a racist. The connections probably deserved to be burnt; they were assholes, animals, guys that would burn you: give you bad stuff and charge you too much, people that would turn you in to the cops if they got busted. Most of the women that hang around jazz musicians are phonies. And as for his prejudice, not wanting white people in his bands, that’s what he feels he should be like. He’s caught up in the way the country is, the way the people are, and he figures that’s the easiest way to go. One time he did hire Bill Evans for his band, but people ranked him so badly and it was such a hassle that I think he became bitter and assumed this posture of racism and hatred. But I feel he’s a good person or he couldn’t play as well as he plays.

Billy Wilson plays like he is. When I knew him, when he was young, he was a real warm, sweet, loving person. And he plays just that way. But if you listen to his tone, it never was very strong; it’s pretty and kind of cracking. It’s weak. And when he was faced with prison—because he got busted for using drugs—he couldn’t stand it. He couldn’t go because he was afraid, and when they offered him an out by turning over on somebody he couldn’t help but do it. He’s a weak person. That’s the way he plays. That’s the way he sounds.

Stan Getz is a great technician, but he plays cold to me. I hear him as he is and he’s rarely moved me. He never knocked me out like Lester Young, Zoot Sims, Coltrane.

John Coltrane was a great person, warm with no prejudice. He was a dedicated musician but he got caught up in the same thing I did. He was playing at the time when using heroin was fashionable, when the big blowers like Bird were using, and so, working in Dizzy Gillespie’s band, playing lead alto, he became a junkie. But he was serious about his playing so he finally stopped using heroin and devoted all his time to practicing. He became a fanatic and he reached a point where he was technically great, but he was also a good person so he played warm and real. I’ve talked to him, talked to him for hours, and he told me, “Why don’t you straighten up? You have so much to offer. Why don’t you give the world what you can?” That’s what he did. But success trapped him. He got so successful that everyone was expecting him to be always in the forefront. It’s the same thing that’s happening to Miles right now. Miles is panicked. He’s stopped. He’s got panicked trying to be different, trying to continually change and be modern and to do the avant-garde thing. Coltrane did that until there was no place else to go. What he finally had, what he really had and wanted and had developed, he could no longer play because that wasn’t new anymore. He got on that treadmill and ran himself ragged trying to be new and to change. It destroyed him. It was too wearing, too draining. And he became frustrated and worried. Then he started hurting, getting pains, and he got scared. He got these pains in his back, and he got terrified. He was afraid of doctors, afraid of hospitals, afraid of audiences, afraid of bandstands. He lost his teeth. He was afraid that his sound wasn’t strong enough, afraid that the new, young black kids wouldn’t think he was the greatest thing that ever lived anymore. And the pains got worse and worse: they got so bad he couldn’t stand the pain. So they carried him to a hospital but he was too far gone. He had cirrhosis, and he died that night. Fear killed him. His life killed him. That thing killed him.

So being a musician and being great is the same as living and being a real person, an honest person, a caring person. You have to be happy with what you have and what you give and not have to be totally different and wreak havoc, not have to have everything be completely new at all times. You just have to be a part of something and have the capacity to love and to play with love. Harry Sweets Edison has done that; Zoot Sims has done that, has finally done that. Dizzy Gillespie has done that to a very strong degree. Dizzy is a very open, contented, loving person; he lives and plays the same way; he does the best he can. A lot of the old players were like that—Jack Teagarden, Freddie Webster—people that just played and were good people.

Jealousy has hurt jazz. Instead of trying to help each other and enjoy each other, musicians have become petty and jealous. A guy will be afraid somebody’s going to play better than him and steal his job. And the black power—a lot of the blacks want jazz to be their music and won’t have anything to do with the whites. Jazz is an art form. How can art form belong to one race of people? I had a group for a while—Lawrence Marable was playing drums, Curtis Counce was playing bass—and one night I got off the stand, we were at Jazz City, and a couple of friends of mine who were there said, “Hey, man, did you realize what was happening? Those cats were ranking you while you were playing, laughing and really ranking you.” I said, “You’re kidding, man!” I started asking people and I started, every now and then, turning around real quick when I’d be playing. And there they were, sneering at me. Finally I just wigged out at Lawrence Marable. We went out in front of the club and I said, “Man, what’s happening with you?” And he said, ‘Oh , fuck you! You know what I think of you, you white motherfucker?” And he spit in the dirt and stepped in it. He said, “You can’t play. None of you white punks can play!” I said, “You lousy, stinking, black mother-fucker! Why the fuck do you work for me if you feel like that?” And he said, “Oh, we’re just taking advantage of you white punk motherfuckers.” And that was it. That’s what they think of me. If that’s what they think of me, what am I going to think of them? I was really hurt, you know; I wanted to cry, you know; I just couldn’t believe it—guys I’d given jobs to, and I find out they’re talking behind my back and, not only that, laughing behind my back when I’m playing in a club!

There’s people like Ray Brown that I worked with, Sonny Stitt, who I blew with, black cats that played marvelous and really were beautiful to me, so I couldn’t believe it when these things started happening. But you’re going to start wondering, you’re going to be leery, naturally, and when you see people that you know .. . I’d go to the union and run into Benny Carter or Gerald Wilson and find myself shying away from them because I’d be wondering, “Do they think, Oh , there’s that white asshole, that Art Pepper; that white punk can’t play; we can only play; us black folks is the only people that can play!’?” That’s how I started thinking and it destroyed everything. How can you have any harmony together or any beauty when that’s going on? So that’s what happened to jazz. That’s why so many people just stopped. Buddy DeFranco, probably the greatest clarinet player who ever lived, people like that, they just got so sick of it; they just got sick to death of it; and they had to get out because it was so heartbreaking.

But all that happened later on. In 1951, musically at least, I had the world by the tail. That was the year I placed second, on alto saxophone, in the down beat jazz poll. Charlie Parker got fourteen votes more than me and came in first.

At the end of 1951 I quit Kenton’s band. It was too hard being on the road, being away from Patti, and I grew tired of the band. I knew all the arrangements by memory and it was really boring. I didn’t get a chance to stretch out and play the solos I wanted to play or the tunes. I kept thinking how nice it would be to play with just a rhythm section in a jazz club where I could be the whole thing and do all the creating myself. As far as the money went, the money never changed. I was one of the highest paid guys in the band, especially among the saxophone players; Stan didn’t think that sax players were the same caliber as brass players or rhythm, and we had to play exceptionally loud and work real hard because we had ten brass blowing over our heads. Also the traveling got to be unbearable. At first I enjoyed it, but after a while, being nine months out of the year on the road, one-nighters every night . . . Sometimes we’d finish a job, change clothes, get on the bus, travel all night long, get to the next town in the daytime, check in and try to get some sleep, and then go and play the job. Sometimes the trip was so long we’d leave at night after the job and be traveling up until the time to go to the next one. We’d have to change clothes on the bus and go right in and play.

Also I became more and more hooked and I went through some unbelievable scenes—running out of stuff on the road, not being able to score, having to play, sick, sitting on the stand spitting up bile into a big rag I kept under the music stand. I guess I looked sort of messed up. People started talking. Kenton became more and more suspicious. I imagined he knew I was doing more than drinking and smoking pot. So it seemed best that I leave the band and try to do something on my own, and I gave my notice. A lot of us quit at the same time. Shelly Manne quit. Shorty Rogers quit.

At first I was apprehensive. I had a lot of bills and I had a habit, so right away I did some recording with Shorty. One was Shorty Rogers and His Giants, and on one of the sides, ‘Over the Rainbow,” I was featured all the way through and got great reviews. It became one of the most popular things I’ve done. Then I formed a group of my own. I got Joe Mondragon and on drums Larry Bunker, who also played vibes. We worked out some things which we could do without the drums while he played vibes, or if he did a ballad I’d sit in on the drums and play a slow beat with the brushes. I got Hampton Hawes, an exceptional pianist. It was just a quartet, but it was very versatile.

Because I had my own group, I wanted to do my own material, tunes that would express my personality, not just standards. I had fooled around writing little things out when I was with Kenton. Now I tried writing seriously and found I had a talent for it. I wrote a ballad for my daughter, Patricia, probably the prettiest thing I’ve written to this day, and I wrote a real flag-waver, a double-fast bebop tune, very difficult, and I named it “Straight Life.”

We worked at the Surf Club and got a great review in down beat. In that same issue, announcing my starting a group of my own, I was written up in another article with another new leader who was going to throw his hat in the jazz band ring and see if he could make it, and that person was Dave Brubeck. We all know now, anyone that follows jazz, that Brubeck became, and still is, one of the outstanding leaders of a jazz group, but at that time, if you read the articles, I was the one they felt was more talented and the one that would make it bigger and make more money and be more popular. I was more of a jazz player. I swung more.

Everything was perfect. I bought a tract house on my GI bill. I had finally gotten to know my daughter and was just mad about her, really loved her. We had a little white poodle named Suzy, and I had a car. I had everything. I was making good money and I didn’t use any of that money on my habit—I was dealing a little bit of stuff to musicians, friends of mine, to support my habit. And I felt that I wasn’t doing anything wrong because I wasn’t taking food out of my child’s and my wife’s mouths by using. But I was really strung out.

I realized I had to get away from the stuff. In the latter part of 51 there began to be newspaper stories about dope. It was beginning to hit the limelight. I realized that things weren’t going to be the same, things were going to tighten up. And that meant either I had to kick or I had to go to jail. That would really ruin my career. I was thinking how nice it would be to just stop, be cool, and not pay any of the real heavy dues that you usually have to pay. So that’s what my thinking was when my dad came out to the house I’d bought in Panorama City and asked me if I’d like to come and have a drink.

My mother had gone to my dad, who was living in Long Beach, and she told him I was using. I had asked her not to say anything to him because he hated junkies; he’d always told me don’t ever do that. But he found out and came to me and said, “Let’s go out and have a drink.” He used to come with Thelma, but this time he came alone and he said he wanted to talk to me.

We went and had a drink, and then he looked at me, and he put his hand on my arm. We were in a bar in Van Nuys, a bar I later worked in with a western band. He said, “When did you start on that stuff?” He put his arm around me and got tears in his eyes. And the way he put it to me I knew that he knew. I think at first I tried a feeble “What do you mean?” But he grabbed my arm. I had a short-sleeved shirt on. I had marks all over my arm. He said, “You might as well be dead.” He said, “How did it happen?” So we talked and I tried to explain to him. I had tried to minimize the feelings I had, but it was so good to be able to tell somebody about it, to let him know how awful I felt and how really scared I was. He said, “What are we going to do?” I said, “Oh God, I don’t know. I want to stop.” He said, “Tell me the truth, if you don’t want to stop nothing is going to do you any good.” We talked and talked. Before he’d even come to me he’d inquired and found a sanitarium in Orange County, and they said they’d take me in. He made sure the police wouldn’t hear about it; I wouldn’t be reported. He said, “Will you go to this place?” I was afraid because I was afraid to kick, and I was afraid I might goof, and I didn’t want to disappoint my dad. I felt miserable when I saw how miserable he felt. He said, “Anything I can do, no matter what it costs, don’t worry about it. Don’t worry about anything—I’ll take care of you.” That’s when he started crying, and we hugged each other, and we were in this bar, and it was really strange, but I felt wonderful because after all these years I felt that I’d reached my dad and we were close. And so he asked me if I’d go to the sanitarium, and I saw that he wanted me to real bad, and so I said yes, alright, that I would go.

(Sammy Curtis) As to drugs, it’s like the thing going on now. It’s a peer thing. A lot of guys are doing it, gettin’ stoned. It did feel good. People enjoy feeling good. You don’t know what it’s going to lead to. You don’t think of that. I’m a follower of Jesus now, and I look at everything spiritually, so I think that anyone drinking, getting stoned, you name it, is looking for the Lord. They’re looking for something greater but they don’t know how to go about it, to find it, and unfortunately, in the search they fool around getting stoned, and it feels better. But it’s a temporary and destructive thing. I’ve been there, and getting closer to the Lord feels much better. It’s cheaper and it’s constructive not destructive.

DOPE MENACE KEEPS GROWING

Dope is menacing the dance band industry. It has become a major threat and unless herculean effort is made by everyone concerned to halt its spread, it may well wreck the business. We are not talking about marijuana, benzedrine, or nembutal, although these are the first steps leading to the evil.

We are referring to real narcotics, heroin principally, and too many well-known musicians and vocalists are “hooked,” as they say in the vernacular. This is serious business and it constitutes a triple threat to the future of dance music.

It is demolishing the professional as well as the personal careers of the addicts themselves, many of whom cannot be spared from the ranks of working musicians because of their talent.

It is giving a bad name to ALL musicians and jeopardizing their living. We know instances in which bookings have been refused to clean units and bands because of undeserved reputation.

Most important of all, the example set by musicians who are addicts and who also are well known, is a wrong influence on younger musicians and on youngsters who may become musicians.

down beat usually has not given prominent display to news stories about musicians who run afoul of the law because of their habit. We did not wish to be accused of sensationalism. We knew, of course, that Miles Davis, the trumpet star, and drummer Art Blakey were picked up recently in Los Angeles on a heroin charge. We did not print it.

Now we are becoming convinced that we are doing a disservice to the industry by not giving wider publicity to such facts. We are beginning to believe that we should name names and state facts, even in the instances of musicians who die from the habit, without attempting to thinly disguise the cause of death as has been done in two or three cases recently.

The grapevine is flooded with rumors and rumors of rumors. A name girl vocalist and her musician husband both are said to be hooked. One of the five top tenor sax stars has flipped, it is reported. Another femme singer, who has been in trouble before, walked out after playing three nights of a two week club engagement because her chauffeur was picked up with heroin capsules in his possession and the law began to stalk her again.

We can’t print names on the basis of rumors alone, even those which seem to be substantiated. There must be an arrest or other official record. When there is, and it is only a matter of time in nearly all cases, down beat intends to print it as a small effort to help stamp out this traffic.

One name band leader has seen the light. He is eliminating, one by one, his sidemen who are known to be using the stuff. There have been half a dozen replacements in his band recently. Other leaders should follow his example. It’s a tough decision to make, turning out an otherwise capable instrumentalist who may well have stellar talent. But it’s better than having the entire structure collapse.

It’s a pity, too, that such musicians should practically be deprived of making a living by the only means they know. Too many of them, however, are not making a living even when they are working. The dope pusher takes most of it. It’s better that they should be forced to work out their own destiny alone, rather than be permitted to remain and infect others, like a rotten apple in a barrel, down beat, November 17, 1950. Copyright 1950 by down beat. Reprinted by special permission.

Perspectives CRITIC DEMANDS JUNKING OF WEAKLING JAZZMEN by Ralph J. Gleason

The most important question in the music business today is not who’s going to make the next hit record, but rather is something nobody talks about, particularly for publication.

Apparently operating on the ancient myth that you can conceal illness by not recognizing its existence, nobody, from bandboy and sideman up to bandleader and booker, will speak openly and frankly on the cancer that is infecting the business. I don’t have to state it any plainer than that for you to know exactly what I’m talking about.

Jazz Is Big Business Jazz is big business today. It’s an important and money-making part of every major record company’s activities and a major part of most minor firms’ work. The jazz clubs flourish all over the country. In the opinion of a veteran publicist in San Francisco, a man connected with show business, the entertainment world and publicity for years, the jazz clubs are a strong part of the backbone of the entertainment field today and in the near future will be the biggest thing in the business.

Today’s youngsters are the potential night club patrons of ten years from now, and what today’s kids want is jazz. They are giving up the Joe E. Lewises for the John Lewises and the Sophie Tuckers for the Sarah Vaughans. Every year the older entertainment world loses another generation of customers. And the new order gains one.

Time To Clean House With this in mind, please consider the possibility that it is time for the musicians, the jazz fans, and the musicians’ union if necessary, to clean house. But good. It’s up to bandleaders and bookers, sidemen and managers to see to it that the cancer is contained, that the infection is stopped and a thriving business, that is also an art and a way of life, is not penalized by the twisted attitudes and hysterical flight from reality of a very few. And they are, relatively, a few. Even though they may be a talented, articulate, and amazingly active few.

How can you respect a man who does not respect himself? There is no reality on Cloud 9, and there is no clearer perception of life. If the music business, itself, doesn’t do something about it, we will all be losers in the long run. Frankly, I can think of no re-orientation too severe for certain of our so-called stars for their behavior in recent years. An addict is a shame and a disgrace to the very word “musician.”

“Special Privilege” Gone Time was when camaraderie between the races and the colors and the factions in music was the rule. The residue of history when musicians were strolling players, a group apart, and as artists and special human beings enjoyed special privileges. It’s getting so the word is one of opprobrium rather than praise.

Sure the papers exaggerate; sure the hysterical columnists shoot off a lot of nonsense. But you know what’s happening, don’t you? Is it good? No one can cure it but you. It’s time the hipsters got their hip cards punched, but in the right place, down beat, December 2, 1953. Copyright 1953 by down beat. Reprinted by special permission.

(Shelly Manne) Drug use was prevalent among musicians then. That was why I originally left New York. People hitting on me for money to score. Leave something on the bandstand, turn around, and it’s gone. Friendship goes right out the window. People turn into animals. But there are different extenuating circumstances in everybody’s life: the need to be accepted by a group of peers who maybe are using drugs or alcohol at the time, the need to be accepted as one of the guys, the need to be considered hipper by doing that, by being a farout cat, or the discontent with one’s own playing. Maybe he feels that a stimulant or a depressant might somehow enable him to get his head together so he can cut the crowd out and get totally into his playing. Who knows. There’s a hundred reasons why. It might be something in your personal life which a friend wouldn’t necessarily know about, in your background, in your bringing up, in your environment. It’s too hard for me to speculate on why a guy would use heavy drugs or heavy alcohol. I know that to do it just for fun — smoke some pot, take a few drinks with the guys, just partying it up — or because there’s a lot of tension on the road, just as a release, was cool. We used to have a lot of fun. We’d get stoned or something and just enjoy ourselves. But when you start getting into heavy drugs, you’re getting into another area, and it’s a terrible vicious circle because it’s a losing battle all around. You’re not only leading a life on the road that is debilitating to your body, to use heavy drugs as a relief from the stress of being on the road creates another disability to your body. And finally your body breaks down, and finally you break down, and finally you have no control or will power, and the whole thing just goes down the toilet.

I was fortunate because drugs scared the hell out of me. When I was young, in New York, playing on Fifty-second Street, when I was eighteen I looked fifteen, and all the musicians I was playing with—Ben Webster, Coleman Hawkins, Trummy Young, Dizzy—all those musicians, kinda were very protective. Even when I hung out in a saloon, the White Rose, on Fifty-second Street, with all those guys and somebody’d offer me a drink (I didn’t like alcohol), they would put them down, “No, give him a Coke.” I’m very grateful to them for that, being protected like that. And, of course, what helped me, too, was being accepted by those guys. It gave me strength and confidence. I felt self-assured about what I wanted to do, where I was going.