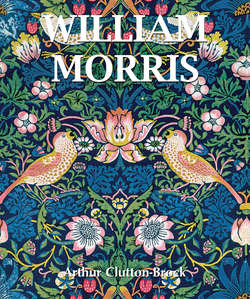

Читать книгу William Morris - Arthur Clutton-Brock - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

Оглавление1. Cosmo Rowe, Portrait of William Morris, c. 1895. Oil on canvas. Wightwick Manor, Staffordshire.

From the middle of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century, we have passed through a period of aesthetic discontent which continues and which is distinct from the many kinds of discontent by which men have been troubled in former ages. No doubt aesthetic discontent has existed before; men have often complained that the art of their own time was inferior to the art of the past; but they have never before been so conscious of this inferiority or felt that it was a reproach to their civilisation and a symptom of some disease affecting the whole of their society. We, powerful in many things beyond any past generation of men, feel that in this one respect we are more impotent than many tribes of savages. We can make things such as men have never made before; but we cannot express any feelings of our own in the making of them, and the vast new world of cities which we have made and are making so rapidly, seems to us, compared with the little slow-built cities of the past, either blankly inexpressive or pompously expressive of something which we would rather not have expressed. That is what we mean when we complain of the ugliness of most modern things made by men. They say nothing to us or they say what we do not want to hear, and therefore we should prefer a world without them.

For us there is a violent contrast between the beauty of nature and the ugliness of man’s work which most past ages have felt little or not at all. We think of a town as spoiling the country, and even of a single modern house as a blot on the face of the earth. But in the past, until the eighteenth century, men thought that their own handiwork heightened the beauty of nature or was, at least, in perfect harmony with it. We are aware of this harmony in a village church or an old manor house or a thatched cottage, however plain these may be; and wonder at it as a secret that we have lost.

Indeed, it is a secret definitely lost in a period of about forty years, between 1790 and 1830. In the middle of the eighteenth century, foolish furniture, not meant for use, was made for the rich, both in France and in England; furniture meant to be used was simple, well made, and well proportioned. Palaces might have been pompous and irrational, but plain houses still possessed the merits of plain furniture. Indeed, whatever men made, without trying to be artistic, they made well; and their work had a quiet unconscious beauty, which passed unnoticed until the secret of it was lost. When the catastrophe came, it affected less those arts such as painting, which are supported by the conscious patronage of the rich, than those more universal and necessary arts which are maintained by a general and unconscious liking for good workmanship and rational design. There were still painters like Turner and Constable, but soon neither rich nor poor could buy new furniture or any kind of domestic implement that was not hideous. Every new building was vulgar or mean, or both. Everywhere the ugliness of irrelevant ornament was combined with the meanness of grudged material and bad workmanship.

At the time no one seems to have noticed this change. None of the great poets of the Romantic Movement, except perhaps Blake, gives a hint of it. They turned with an unconscious disgust from the works of man to nature; and if they speak of art at all it is the art of the Middle Ages, which they enjoyed because it belonged to the past. Indeed the Romantic Movement, so far as it affected the arts at all, only afflicted them with a new disease. The Gothic revival, which was a part of the Romantic movement, expressed nothing but a vague dislike of the present with all its associations and a vague desire to conjure up the associations of the past as they were conjured up in Romantic poetry. Pinnacles, pointed arches and stained glass windows were symbols, like that blessed word Mesopotamia; and they were used without propriety or understanding. In fact, the revival meant nothing except that the public was sick of the native ugliness of its own time and wished to make an excursion into the past, as if for change of air and scene.

But this weariness was at first quite unconscious. Men were not aware that the art of their time was afflicted with a disease, still less had they any notion that that disease was social. They had lost a joy in life, but they did not know it until Ruskin came to tell them that they had lost it and why. In him æsthetic discontent first became conscious and scientific. For he saw that the prevailing ugliness was not caused merely by the loss of one particular faculty, that the artistic powers of men were not isolated from all their other powers. He was the first to judge works of art as if they were human actions, having moral and intellectual qualities as well as æsthetic; and he saw their total effect as the result of all those qualities and of the condition of the society in which they were produced. So his criticism gave a new importance to works of art, as being the clearest expression of men’s minds which they can leave to future ages; and in particular it gave a new importance to architecture and all the applied arts, since, being produced by cooperation and for purposes of use, they express the general state of mind better than those arts, such as painting, which are altogether the work of individual artists. All this Ruskin saw; and he saw that the building and applied art of his own time were bad as they had never been before. And this badness troubled him as if it were something corrupt and sinister in the manners of men and women about him. It was not merely that he missed a pleasure which other ages enjoyed; he also was aware of a positive evil from which they had been free. Art for him was not a mere superfluity that men could have or not as they chose; it was a quality of all things made by men, which must be good or bad, and which expressed some goodness or badness in them. So, from being a critic of art, he became a critic of society, and, after writing about old buildings and modern painters, he wrote about political economy, about the order and disorder of that society which produced all the ugliness of his own time.

2. William Morris and William Frend De Morgan (for the design) and Architectural Pottery Co. (for the production), Panel of tiles, 1876. Slip-covered tiles, hand-painted in various colours, glazed on earthenware blanks, 160 × 91.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

3. Tulip and Trellis, 1870. Hand-painted in blue and green on tin-glazed earthenware tile, 15.3 × 15.3 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

4. William Morris (for the design?) and Architectural Pottery Co. (for the production), Four Pink and Hawthorn Tiles, 1887. Slip-covered, hand-painted in colours and glazed on earthenware blanks, 15.5 × 15 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Now many men before him had denounced the evils of their day; but he was the first to be turned into a prophet by aesthetic discontent, and the fact that he was so turned was one of great significance. He was a genius who detected a new danger to the life of man and who expressed an uneasiness spreading among the population, though he alone was conscious of it. He was and remained a critic, one who experienced and reasoned about his experiences rather than one who created. His rebellion was one of thought rather than of action, and the discoveries that he made had still to be confirmed by actual experiment. It was possible for men to say of him that he was a pure theorist; and indeed he often theorised rashly and wilfully and made many glaring errors of fact. He had the intuition of genius but not the knowledge of practice; he seemed often to speak with more eloquence than authority.

But he was followed in his rebellion by another man of genius who was by nature not a critic but an artist, that is to say, a man whose chief desire was to make things and to express his own values in the making of them. As Ruskin turned from the criticism of works of art to the criticism of society, so William Morris turned from the making of works of art to the effort to remake society. The biographer Mackail has said of him that he devoted the whole of his extraordinary powers towards no less an object than the reconstitution of the civilised life of mankind. That is true, and it had never been true of any artist before him; at least no artist had ever been turned from his art to politics because he was an artist. Morris was so turned; and for that reason he is the chief representative of that æsthetic discontent which is peculiar to that time.

One might have expected that he would be the last man to feel it; since he could himself make whatever beautiful things he wanted. Not only could he express his desire for beauty in poetry, but he could also express his own ideas of beauty in the work of his hands. However ugly the world outside him might be, he could make an earthly Paradise for himself, and could enjoy all the happiness of the artist in doing so. There are some men of great gifts who can never be content with their exercise; but Morris was as happy in making any of the hundred different things that he made so well as a child is happy at play. He knew early in life what he wanted to do; and he was as free as any man could be to do it. At the age of twenty-one he became his own master, with a comfortable fortune. His father was dead; and, though his mother had cherished the hope that he would become a bishop, she suffered her disappointment quietly. He began at once to practice several arts, and satisfied both himself and the public in his practice of them. So he had no quarrel with the world so far as his own well-being was concerned; indeed he can be compared, for universal good fortune, only with his famous contemporary Leo Tolstoy. And he was like Tolstoy too in this, that his private happiness could neither enervate nor satisfy him. Some men rebel against society because they are unhappy; but Tolstoy and Morris put away their happiness to rebel. Each of them in his own earthly Paradise, heard the voice of unhappiness outside it; each saw evil in the world which made his own good intolerable to him.

They rebelled for different reasons; and to many they have both seemed irrational in their rebellion, for they were both drawn from work for which they had genius to work for which they had none. Tolstoy was not born to be a saint, nor was Morris born to be a revolutionary, and the world has lamented the perverse waste of natural powers which their rebellion caused. Indeed, in the case of Morris it has seemed to many that he quarreled with the world on a trivial point. To them art is a pleasant ornament of life; but if, for some reason, it is one that society at present cannot excel in, they are well content to do without it, much more content than they would be to do without golf or sport. To them Morris is merely a man who made a great fuss about his own particular line of business. Naturally there was nothing like leather to him; but men in another line of business cannot be expected to pay much heed to him.

Morris himself, however, held that art is everybody’s business, whether they are themselves artists or not. And by art he, like Ruskin, did not mean merely pictures or statues. Indeed, he thought little of these compared with all the work of men’s hands that used to be beautiful in the past and now is ugly. The ugliness of houses, tables and chairs, clothes, cups and saucers, in fact of everything that men made, whether they tried to make it beautiful or were content that it should be ugly – this universal ugliness at first troubled him like a physical discomfort without his knowing why. And at first he, being himself a man of action and an artist, merely tried to make beautiful things for himself and others. But gradually he came to see that this single artistic effort of his would avail nothing in a world of ugliness, that all the conditions of our society favoured ugliness and thwarted beauty. He saw, too, from his own experience, that beauty was a symptom of happy work and ugliness of unhappy; and so he became aware that, our society was troubled by a new kind of discontent, which it expressed in the ugliness of all that it made.

5. William Frend De Morgan (for the design) and Sands End Pottery (for the production), Panel, 1888–1897. Buff-coloured earthenware, with painting over a white slip, 61.4 × 40.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

6. The Months of the Year, 1863–1864. Hand-painted tiles. Old Hall, Queens College, Cambridge.

7. Edward Burne-Jones and Lucy Faulkner, Sleeping Beauty, 1862–1865. Hand-painted on tin-glazed earthenware tiles, 76.2 × 120.6 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

This he knew, as no one else knew it, from his own happiness in his work and the beauty through which he expressed it. If he had been a poet alone, he might never have known it except as a theory of Ruskin’s; but being a worker in twenty different crafts he knew it more surely than Ruskin himself; and the knowledge became intolerable to him, so that he seemed to himself to be a mere idler while he was only doing his own work and enjoying his own happiness in it. He could not rest until he had tried to show other men the happiness they had lost, whether they were rich or poor, whether they were toiling without joy themselves or living on the joyless labour of others. Many men have rebelled against society and have preached rebellion because of the fearful contrast between riches and poverty; but it was not poverty that made Morris rebel so much as the nature of the work, which in our time most poor men have to do. He believed that their work was joyless as it never had been before; and that, not poverty, was to him the peculiar evil of their time against which, as a workman himself, he rebelled and wished the poor to rebel. They knew, of course, that they were poor, but they were not aware of this peculiar penalty of their poverty; and he was determined to make both them and the rich aware of it. He would open men’s eyes to the meaning of his prevailing ugliness. He would make the rich see that they too were poorer than a peasant of the thirteenth century, in that there was no beauty of their own time in which they could take delight as if it were a general happiness, but only an ugliness that must dispirit them like a general unhappiness.

So he turned from his art to preach to men like a prophet; the value of his preaching lay in the fact that he was attacking a new evil that had grown up while men were unaware of it. And because the evil was new, they paid little attention to him at first; for men are as conservative in their discontents as in other things, and civilisation is always being threatened by new dangers while they are thinking of the old. To Morris the chief danger of our civilisation seemed to be the growth of a barbarism caused by joyless labour and of a discontent that did not know its cause. He feared lest the great mass of men should gradually come to believe that our society was not worth the sacrifices that were made for it; indeed, he sometimes hoped that it would be destroyed by this belief. Yet he was determined to do his best to save it, if it could be saved and transformed. For, as Mackail puts it, he believed that it could not be saved except by a reconstitution of the civilised life of mankind. The rich must learn to love art more than riches, and the poor to hate joyless work more than poverty. There must be a change in values that would mean a change of heart; and Morris did not despair of that change. Yet he knew that he was alone in his efforts to bring it about; for though he consorted and worked with other Socialists, his desires and hopes, and therefore his methods, were different from theirs. They were, many of them, able and devoted men who hoped by means of organisation to change the economic structure of society so that there should be no more very rich or very poor. Among these he was like a saint among ecclesiastics; for he desired something far beyond a more equal distribution of wealth, and he would not have been at all content with a world in which men lived and worked as they do now but without extreme poverty or riches. Other Socialists protested against the present waste of our superfluous energy; he told men what they might do with their superfluous energy when they had ceased to waste it. There is a common notion, favoured by the books of writers like Bellamy, that a Socialist state would be dull, with every one living as people live now in a prosperous middle-class suburb. Indeed, Bellamy tells us with prophetic rapture that in his Utopia there will be no need of umbrellas since there will be porticos over all the side-ways in every town. But Morris wanted something more in a reorganised society than a municipal substitute for umbrellas. It is one of the worst failures of our society that it has forgotten pleasure for comfort; that it thinks more of the armchair than of the dance. Morris tried to make men wish, like himself, for pleasure more than for comfort, and in the Utopia that he dreamt of, there were armchairs for the old, no doubt, but dancing for the young. Indeed, in his ideal state all life and all labour would be a kind of dance rather than a comfortable and torpid repose. That is to say, every activity of man would be made delightful by the superfluous energy of a civilised fellowship. We should enjoy our common work, as the craftsmen of the thirteenth century must have enjoyed building a great cathedral together; and our enjoyment would manifest itself in the beauty of all that we made. That was what Socialism meant to him, and all its machinery was only a means to that end.

It is easy to call him a visionary; but visionaries are necessary to every great movement, because they alone can give it direction, and they alone can make men desire the goal towards which they move. It is not enough to preach peace by talking of the horrors of war; for men are so made that they prefer horrors to dullness. You must persuade them that peace means a fuller and more glorious life than war, if you would make them desire it passionately. Morris said that our present society was in a state of economic war, and that for that reason it was anxious, joyless and impotent, like the life of a savage tribe engaged in incessant vendettas. The economic peace which he desired was one in which men would have leisure and power to do all that was best worth doing; and he hoped to bring that peace about by filling them with his own desire to do what was best worth doing. And as the saint affects men more by his vision of Heaven than the ecclesiastics affect them with all their organisation and discipline, so, it may be, Morris has done more for Socialism than all the scientific Socialists. For he knew quite clearly what he wanted in life and no one can say that he wanted what was not desirable. The world distrusts philanthropists and reformers of all kinds because they do not in their own lives convince the world that they are good judges of happiness. If they want us to be like themselves, we look at them and decide that we do not want to be like them. But no one could know Morris or his way of life without wanting to be like him. No one could say that he set out to reform the world without having first made a good business of life himself. When he tells us how to be happy and why we miss happiness he speaks with authority and not as the philanthropists; indeed, his ideas of what life should be commend themselves to us even without his authority, and there are many now who share them without knowing their origin.

8. Ariadne, 1870. Polished ceramic tile. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

9. Angels, undated. Tile Panel. St John the Baptist Church, Findon, Sussex.

10. Edward Burne-Jones and Lucy Faulkner, Cinderella, 1863. Tile panel, overglazed polychrome decoration on tin-glazed Dutch earthenware blanks in ebonized oak frame, 71 × 153 cm. Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

11. Venus, 1870. Miniature. Ink, gouache and guilding on paper, 27.9 × 21.6 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

12. Anonymous, Nobleman (probably Wolfert Van Borssel) from the Metamorphoses, late 15th century. Parchment, 45 × 33.5 cm. Private collection, Bruges.

There was a time when the world was more interested in Morris’s ideas than in Morris himself, and his influence was greater than his name. In his art he affected the art of all Europe so profoundly that what he did alone seems to be only the product of his age. As a poet he is commonly thought of as the last and most extreme of the romantics; but his later poetry, at least, is quite free from the romantic despair of reality and nearly all of it is free from romantic vagueness. When Morris described the world that is not, he was, as it were, making plans of the world as he wished it to be; and he was always concerned with the future even when he seemed most absorbed in the past. In that respect he differed from all the other romantic poets, and in his most visionary poetry he tells us constantly what he valued in reality, what is best worth doing and being in life. All that he wrote, in verse or prose romance, is a tale of his own great adventure through a world that he wished to change; and we cannot yet tell how great a change he has worked or will work upon it. But we know already that he was one of the greatest men of the nineteenth century and, with Tolstoy, the most lonely and distinct of them all. In this book I have tried to give some description of his greatness rather than to write his life. He is the subject of a volume, not because he was a poet or an artist, but because the minds of men would have been different from what they are if he had never been born. Yet his art and his poetry were a great part of his action; indeed he was artist and poet before he had any conscious intention of changing the world, and the world has listened to his advice because he was an artist and a poet.

He was also, I believe, a greater and far more various poet than most people think. He is commonly known as a spinner of agreeable but shadowy romances, both in verse and in prose. I have therefore written at some length in the effort to show that he was far more than that. There are small men who have a specific gift for literature or art and whose work pleases us because of this gift, in spite of their smallness. But Morris was a great man, great in intelligence, in will, and in passion; and the better one knows his work, the more one sees that greatness in all of it. All those who knew him well recognised it, even if they cared nothing for poetry or art; they fell under his influence as men fell under the influence of Napoleon, and that although they had none of Napoleon’s love of power. This book is written by someone who did not know him, and it is an attempt to show the nature of his influence and of his greatness in his works. He did so many things that it is impossible to speak of them all in a volume of this length; and he was never the centre of a circle like Doctor Johnson or Rossetti. Those who dealt directly with him felt that he made the issues of life and of art clearer to them; and that, we may be sure, he will continue to do for many generations yet unborn.

13. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Beatrice Meeting Dante at a Marriage Feast, Denies Him Her Salutation, 1855. Watercolour on paper, 34 × 42 cm. Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.