Читать книгу William Morris - Arthur Clutton-Brock - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Early Years, a Promising Future

Childhood and Youth

ОглавлениеWilliam Morris was born at Walthamstow on March 24, 1834. There was nothing in the circumstances of his childhood to make him unlike other men of his class. His father was partner in a prosperous firm of bill-brokers and the family remained well-to-do after his death in 1847. Morris’s childhood was happy but not remarkable. He gave no special proofs of genius, but showed the same character and tastes as in later years. He liked to wander about Epping Forest and knew the names of birds, learnt whatever he wished to learn easily and remembered it exactly, and was both passionate and good-natured.

One story told of him shows what he wished to learn and how well he remembered it. At the age of eight he saw the Church of Minster in Thanet, and fifty years afterwards, not having seen it since, he was able to describe it in detail. This is one proof, among many, that he understood Gothic art as the child Mozart understood music, seeming to recognise in it a language that he knew by nature. This process of recognition continued all through his youth. It was the chief part of his education; it was what distinguished him from other youths of his time; and it was, as we can see now, a sign of his strong natural character and a preparation for the whole of his future life.

To Morris a Gothic building was not merely something beautiful or romantic or strange. He did not enjoy it only as most of us enjoy a beautiful tune. It had for him that more precise meaning which music had for the young Mozart. He saw not only that it was the kind of art he liked, but also why he liked it. For it expressed to him, more clearly than words, a state of being which he felt to be desirable. It was as if the men who had made it were before him in the flesh and he saw them and loved them. Indeed he had that passionate liking for the whole society in which the great works of Gothic art were produced which some of us have for our favourite poets or musicians. And he missed Gothic art from his present as if it were the voice of some dead loved one. Church after church, as he first saw them in his youth, was remembered as if it were the first meeting with a dear friend; and it was fixed in his mind, not only because he enjoyed its beauty, but because it expressed for him that state of being which he loved in it. It was like a face vividly remembered through affection, and all its details were connected with each other in his mind as if they were features.

We must understand this if we are to understand Morris’s early passion for the Middle Ages and all their works. It was not the dry passion of the mere archaeologist who studies the past because it is dead. Morris studied it because he saw it alive. The churches for him were not old, but just built. It was the later buildings of what he called the age of ignorance that to him seemed obsolete, for they expressed nothing that he wanted. Just as the minds of the great artists of the Renaissance leapt back over an intervening time to classical art, so his mind leapt back to the Gothic and found in it the new world that he wished to create.

At the age of thirteen he was sent to Marlborough College, then a new school and lax in its discipline. This was a piece of good fortune for him, for he did not need to be set either to work or to play. He was not an aimless idler, to be kept out of mischief by compulsory games. At Marlborough he had another forest, to roam through and a library of books to read. He had not been taught any craft in childhood; but his fingers were as busy as his mind; and for want of some better employment he exercised them in endless netting, as he exercised his mind by telling endless tales of adventure to his schoolmates. At Marlborough he became aware of the High Church Movement and was drawn into it, so that when he left the school knowing, as he said, most of what was to be known about English Gothic, he went to Exeter College, Oxford with the intention of taking Orders.

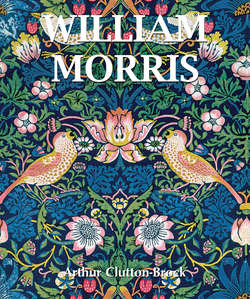

15. Violet and Columbine, 1883. Pattern for woven textile. Private collection.

16. Rose (detail), 1883. Pencil, pen, ink and watercolour on paper, 90.6 × 66.3 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

17. Cray, 1884. Printed cotton, 96.5 × 107.9 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

18. Wandle, 1884. Indigo-discharged and block-printed cotton, 160.1 × 96.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

This was in the Lent term of 1853; and while at Oxford he continued to educate himself much as he had done at school. At Exeter, we are told, there was then neither teaching nor discipline Morris’s tutor described him as a rather rough unpolished youth who exhibited no special literary tastes nor capacity, from which we may guess that they were not close friends. Indeed Morris all his life used the word don as a term of abuse more severe than many strong-sounding words at his command. But Oxford itself, still unblemished in its beauty, delighted him; and he got from it his first notion of what a city should be. Yet it seemed to him a misused treasure of the past, for already he desired a present capable of expressing itself with the same energy and beauty. The present of Oxford seemed to him a mere barbarism, frivolous and pedantic; but for one friend whom he made in his first term, he might have lived a lonely life there. This friend was Edward Burne-Jones, a freshman from King Edward’s Grammar School, Birmingham, who already promised much as an artist, but who, like Morris, meant to take Orders. Neither of them cared much for the undergraduates of Exeter; but there were some of Burne-Jones’s schoolfellows at Pembroke to whom he introduced Morris, and among whom Morris got the society he needed. Canon Dixon, the poet, who was one of these, tells us that at first they regarded Morris simply as a pleasant boy who was fond of talking, which he did in a husky shout:

“He was very fond of sailing a boat. He was also exceedingly fond of single-stick and a good fencer… But his mental qualities, his intellect also, began to be perceived and acknowledged. I remember Faulkner remarking to me, ‘How Morris seems to know things, doesn’t he?’ And then it struck me that it was so. I observed how decisive he was: how accurate, without any effort or formality. What an extraordinary power of observation lay at the base of his casual or incidental remarks, and how many things he knew that were quite out of our way, as, for example architecture.”

In this new world of people and things and ideas Morris was not bewildered or misled by momentary influences. Then, as afterwards, he seemed to know by instinct what he wanted to learn and where he could find it. He had a scent for his own future, little as he knew yet what it was to be; and whatever he did or read was a preparation for it. Already there had begun in England that reaction against all the ideas of our industrial civilisation which Morris himself was to carry further than any. But the ideas were still predominant and were commonly supposed to have a scientific consistency and truth against which only wilfulness could rebel. Yet there was this curious inconsistency in them – that, while they recommended a certain course of action to society which it was to adopt of its own free will, they promised as the mechanical result of that action a state of moral and material well-being to which society would attain without further effort. The will was to make its choice at the start; and then no further choice would be required of it. But this inconsistency was also based upon certain assumptions that do not now seem to us beyond dispute. It was assumed, for instance, that the main end of every society was to become rich; and that it would become rich if individuals were allowed to acquire riches by any means they chose to employ. This license was called freedom; and indeed it meant a complete freedom for those who were rich already, but a freedom merely nominal and legal for those who were poor. They were free to be rich if they could; but the great mass of them could not, and remained in extreme poverty, in spite or rather because of the riches of the few. Thus the national well-being promised did not come about, although great fortunes were made; and the moral well being also failed to equal expectations. Indeed there was an inconsistency between the morality of the individual and the morality of society that was bad for both. The morality of the individual was still supposed to be Christian, except when he was making money. But, as soon as he began to do that he was regarded as a member of a society whose aim only was to make money. Then his Christian morality was superseded by an economic law against which it was merely sentimental to rebel. This kind of inconsistency has always existed; but it has never been so glaring or produced so much moral and intellectual confusion as in England in the nineteenth century. Then it was that we established our reputation as a nation of hypocrites and were confirmed in our national dislike of logic. The great mass of Englishmen wished to be good, according to the Christian pattern; but they also wished to make money and they acquired a notion, implied in their laws and in their habits of thought if never openly stated, that money was the material reward of goodness. But this notion was always proving itself to be untrue. The rich were not identical with the good according to any system of morality known to man, least of all according to the Christian. Yet they were favoured and encouraged by all the laws, and by all the anarchy, of the State. If any one pointed out this inconsistency, he was told that the State, having made its wise choice in favour of riches, had no further choice in the matter. Scientific laws were now operating in favour of the rich and against the poor, and they were no more to be resisted than the law of gravity.

19. Rose, 1877. Colours prints from woodblocks. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

Meanwhile certain people asked themselves how they liked this society, which was settling into a second state of nature; they found that they did not like it at all. Carlyle, for instance, disliked it as much as Jonah disliked Nineveh. In particular he disliked the rich because they were sheltered against reality by the whole structure of society, and because in their shelter they talked and thought about unreal things. He was as sure as Jonah that God in his wrath would some day blow all their comfort away from them; but he had no notion of a civilisation to take the place of that which he wished to destroy, nor of a peace of mind to succeed the complacent torpor against which he raged. His aim was to reduce the minds of men to the first stage of conversion, to that utter humiliation in which they might hear the sudden voice of God. We are used to his denunciations; but to Morris they were new and they assured him that he was right in his own instinctive dislike of all that Carlyle denounced.

As previously mentioned, Ruskin’s rebellion was at first æsthetic; it was a rebellion not merely against the art of his own time, but against all the art of the Renaissance and the ideas expressed in that art. The Stones of Venice was published in Morris’s first year at Oxford; and from the chapter on the Nature of Gothic he learnt that there was reason in his own love of Gothic and dislike of Renaissance architecture. Ruskin points out that in Gothic every workman had a chance of expressing himself, whereas in Renaissance, and in all architecture since, the workman only did exactly what the architect told him to do. Thus Gothic missed the arrogant and determined perfection of Renaissance, but it had an eager life and growth of its own, like that of a State, which recognises the human rights of all its members. There were, of course, different tasks for all the workmen according to their ability, but each to some extent expressed his own will in what he did. To Morris this chapter was a gospel and all his own ideas about art grew out of it; indeed he was unjust to the art of the Renaissance, not merely through a caprice of personal taste, but because it seemed to him that at the Renaissance European society had taken a wrong turn, arriving at the dull follies of the industrial age. He knew, of course, that there were great artists during the Renaissance, but in their work he saw a foreboding of what was to come of it. For him it expressed, however splendidly, a state of mind that seemed wrong, and he refused to be dazzled by the triumphs of Michelangelo, as by the victories of Napoleon.

20. Wandle, 1884. Indigo-discharged and block-printed cotton, 165 × 92 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

21. Little Flowers. Pattern for chintz. Victoria & Albert Museum, London.

If he had been a critic, this prejudice of his against the Renaissance would have been a mere prejudice harmful to his work; but he was to be an artist, and afterwards a revolutionary, that is to say a man of action on both stages. Therefore he rightly and naturally judged all art and all ideas by their practical value to himself. And even when he was an undergraduate at Oxford he saw what would be of practical value to him. He knew already what he wanted both in life and in art and he had only to learn how to do and to get what he wanted.

In the long vacation of 1854 he went abroad, for the first time, to Northern France and Belgium, where he saw the greatest works of Gothic architecture and the paintings of Van Eyck and Memling. He said long afterwards that the first sight of Rouen was the greatest pleasure he had ever known; and Van Eyck and Memling remained always his favorite painters, no doubt because their art was still the art of the Middle Ages practiced with a new craft and subtlety.

In the same year he came of age and inherited an income of £900 a year. Thus he was already his own master and his freedom only determined him to make the best possible use of it. In the next year he and Burne-Jones finally resolved to be artists not clergymen. Morris had been drawn into the High Church Movement, no doubt because it was part of the general reaction against modern materialism and ugliness. But the beliefs which were forming in his mind were not religious, however harmonious with the true Christian faith. He changed his purpose not in any violent reaction against it, but because he had a stronger desire to do something else. He had already begun to write poetry, which he did quite suddenly and with immediate success. Canon Dixon tells how he went one evening to Exeter and found Morris with Burne-Jones. As soon as he entered the room. Burne-Jones exclaimed wildly, “‘He’s a great poet.’ ‘Who is?’ asked we. ‘Why, Topsy.’” Then Morris read them The Willow and the Red Cliff, the first poem he had ever written in his life. Dixon expressed his admiration and Morris replied, “Well, if this is poetry, it is very easy to write.” “From that time onward,” says Dixon, “for a term or two, he came to my rooms almost every day with a new poem.”

Morris destroyed many of his early poems, but some pieces and fragments remain of them and they are, as Dixon thought when he first heard them, quite unlike any other poetry. We can believe, too, that they were easy to write, for they sound as if they had come into his mind as tunes come into the minds of musicians:

Christ keep the Hollow Land

All the summer-tide;

Still we cannot understand

Where the waters glide;

Only dimly seeing them

Coldly slipping through

Many green-lipped cavern-mouths,

Where the hills are blue.

22. Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and John Henry Dearle (for the design) and Morris & Co. (for the production), Holy Grail Tapestry – Quest for the Holy Grail Tapestries – The Arming and Departure of the Knights (II), 1895–1896. High warp tapestry, wool and silk weft on cotton warp, 360 × 244 cm. Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham.

23. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Before the Battle, 1858, retouched in 1862. Transparent and opaque watercolour on paper, mounted on canvas, 41.4 × 27.5 cm. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Morris afterwards became the best storyteller of all our modern poets; but because he had this power of making verse that was almost musical, verse that needed no context or preparation but cast an instant spell upon the mind through the ear, he was always a poet as well as a storyteller. In his life as in his poetry there was the same contrast and yet harmony of the visionary and the practical, and the same power of making the one serve the other. At this time in his poetry he was a pure visionary. Things that delighted his eyes or his mind came into his verse as such things come into dreams. He might, no doubt, have cultivated this poetry of the sub-consciousness; but he was not long content to be only a visionary either in life or in art. It may be that the prose romances, which he began to write in 1855, gave him a disgust of this kind of writing. They too are unlike anything else in English literature, but far inferior to the poems. For that vagueness of sense, which in the verse is combined with a curious intensity of sound, bewilders and disappoints in a prose story, the more so because the style is uncertain and not always suited to the subject. Indeed at this time Morris wrote prose as minor poets write verse, seeming now and then to adopt a sentimental character not his own and to express what he wanted to feel rather than what he did feel. Thirty years later, when he again began writing prose, he was a complete master of it; but in 1855 he first read Chaucer and was turned back from prose to verse, and to verse about subjects he chose consciously.

He and his friends had a young and generous desire to work some great change upon the world. They had vague notions of founding a brotherhood, they saw that the condition of the poor was horrible, they wanted to do something at once; and, not knowing precisely what they wanted to do, they naturally determined to start a magazine. Dixon first proposed it to Morris in 1855 and the whole set were delighted with the idea. Since they had friends at Cambridge they determined that these too should write for it; and so, when it came into being, it was called the Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, though it was nearly all written by Oxford men. The first issue appeared on January 1, 1856, and it ran for twelve issues, appearing monthly. Morris financed and wrote eighteen poems, romances and articles for it. No other contributor came near him in merit except Dante Gabriel Rossetti, whom Burne-Jones had met at the end of 1855 and who already admired Morris’s poetry. Both Tennyson and Ruskin praised the magazine; but it sold few issues, confirming the fears of Ruskin, who said that he had never known an honest journal get on yet.

24. La Belle Iseult, 1858. Oil on canvas, 71.8 × 50.2 cm. Tate Gallery, London.

25. The Adoration of the Magi, 1888. Tapestry woven in wool, silk and mohair on a cotton warp, 345.3 × 502.9 cm. Castle Museum, Norwich.