Читать книгу The Life and Times of Akhenaton, Pharaoh of Egypt - Arthur E. P - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4. THOTHMES IV. AND MUTEMUA.

ОглавлениеWhen Thothmes IV. ascended the throne he was confronted by a very serious political problem. The Heliopolitan priesthood at this time was chafing against the power of Amon, and was striving to restore the somewhat fallen prestige of its own god Ra, who in the far past had been the supreme deity of Egypt, but had now to play an annoying second to the Theban god. Thothmes IV., as we shall presently be told by Akhenaton himself,8 did not altogether approve of the political character of the Amon priesthood, and it may have been due to this dissatisfaction that he undertook the repairing of the great Sphinx at Gizeh, which was in the care of the priests of Heliopolis. The sphinx was thought to represent a combination of the Heliopolitan gods Horakhti, Khepera, Ra, and Atum, who have been mentioned above; and, according to a later tradition, Thothmes IV. had obtained the throne over the heads of his elder brothers through the mediation of the Sphinx—that is to say, through that of the Heliopolitan priests. By them he was called “Son of Atum and Protector of Horakhte, ... who purifies Heliopolis and satisfies Ra,”9 and it seems that they looked to him to restore to them their lost power. The Pharaoh, however, was a physical weakling, whose small amount of energy was entirely expended upon his army, which he greatly loved, and which he led into Syria and into the Sudan. His brief reign of somewhat over eight years, from 1420 to 1411 B.C., marks but the indecisive beginnings of the struggle between Amon and Ra, which culminated in the early years of the reign of his grandson Akhenaton.

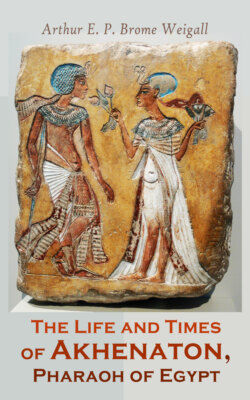

Thothmes IV. slaying Asiatics.

Some time before he came to the throne he had married a daughter of the King of Mitanni, a North-Syrian state which acted as a buffer between the Egyptian possessions in Syria and the hostile lands of Asia Minor and Mesopotamia, and which it was desirable, therefore, to placate by such a union. There is little doubt that this princess is to be identified with the Queen Mutemua, of whom several monuments exist, and who was the mother of Amonhotep III., the son and successor of Thothmes IV. A foreign element was thus introduced into the court which much altered its character, and led to numerous changes of a very radical nature. It may be that this Asiatic influence induced the Pharaoh to give further encouragement to the priest of Heliopolis. The god Atum, the aspect of Ra as the setting sun, was, as has been said, of common origin with Aton or Adonis, who was largely worshipped in North Syria; and the foreign queen with her retinue may have therefore felt more sympathy with Heliopolis than with Thebes. Moreover, it was the Asiatic tendency to speculate in religious questions, and the doctrines of the priests of the northern god were more flexible and more adaptable to the thinker than was the stiff, formal creed of Amon. Thus, the foreign thought which had now been introduced into Egypt, and especially into the palace, may have contributed somewhat to the dissatisfaction with the state religion which becomes apparent during this reign.

Very little is known of the character of Thothmes IV., and nothing which bears upon that of his grandson Akhenaton is to be ascertained. Although of feeble health and unmanly physique, he was a fond upholder of the martial dignity of Egypt. He delighted to honour the memory of those Pharaohs of the past who had achieved the greatest fame as warriors. Thus he restored the monuments of Thothmes III., of Aahmes I., and of Senusert III.,10 the three greatest military leaders of Egyptian history. As a decoration for his chariot there were scenes representing him trampling upon his foes; and when he died many weapons of war were buried with him. Of Queen Mutemua’s character nothing is known; and the attention of the reader may at once be carried on to Akhenaton’s maternal grandparents, the father and mother of Queen Tiy.