Читать книгу Very Special Ships - Arthur Nicholson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

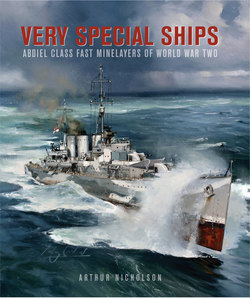

GETTING IT JUST RIGHT

Designing the Abdiel Class

There is nothing like a threat to focus the mind and, as Britain rearmed in response to the threat from Nazi Germany in the 1930s, the Admiralty finally decided what it really needed was a small fast minelayer. In January 1937, the Controller of the Admiralty gave verbal instructions that a sketch design of such a ship should be prepared. They were to be known as ‘fast minelayers’, not ‘cruiser-minelayers’, though they have been frequently referred to as such, even by the enemy. For administrative purposes, they were rated as ‘cruisers and above’.1

For a completely unprecedented type of ship, their design moved along relatively quickly, especially since the Construction Department of the Admiralty was very busy with many other designs at a time of fevered rearmament. At that time, the Director of Naval Construction was Sir Stanley Goodall and his very able assistant was Sir Charles Lillicrap. The Chief of the Naval Staff (the First Sea Lord) approved a sketch design on 19 July 1938 and Goodall submitted specifics of the design and drawings for the approval of the Board of Admiralty on 18 November. The Board approved the design’s legend and drawings on 1 December 1938. In the meantime, tenders from prospective builders were to be invited so that orders might be placed before the end of the year.

During the design process, there were many choices to be made as the design of the fast minelayers began to take shape. At first, the design called for just two twin 4in gun mounts, but this was increased to three. It was proposed at one time to fit two of them aft and one forward and somewhat detailed plans were drawn up,2 sufficient to inspire an artist’s impression of the design. In the end, however, two (‘A’ and ‘B’) were to be fitted forward, one superfiring over the other and one (‘Y’) aft.

During the design process, some bad ideas were rejected. The idea of replacing the 4in dual-purpose guns – which could be used against aircraft or surface targets – with two heavy weather-proof, power-operated 4.7in twin mountings with only 50° of elevation (which were to be fitted in the ‘L’ class destroyers then under development) was fortunately rejected, as they would have been of little use against aircraft. One of the worst ideas, the provision of quadruple 21in torpedo tubes, was also rejected. During the design process, it had to be pointed out that the ‘offensive’ in the term ‘offensive minelayer’ meant the minefield they were to lay rather than the ship itself and the emphasis on maintaining high speed had to be pointed out in connection with additional fittings that would decrease their speed.

Sir Stanley Goodall, Director of Naval Construction during the design of the Abdiel class. (NPG × 89436, undated portrait by Elliott & Fry, © National Portrait Gallery, London)

The result was a class of ships that was larger than any British destroyer and smaller than any British cruiser and plenty faster than any of them. Specifically, at 2650 tons standard displacement, the Abdiels were larger than the largest British destroyers of the day, the 1850-ton ‘Tribal’ class, an example of which was the legendary HMS Cossack, and were smaller than the smallest modern British light cruisers of the day, the 5419-ton3 Arethusa class, an example of which was the similarly legendary HMS Penelope. The Abdiels’ displacement was 3780 tons in deep condition, their length overall was 417ft 11in, their maximum beam was 40ft, their draught forward was 10ft and 12ft aft.4

Many regarded the Abdiels as very attractive ships. Rear Admiral Sir Morgan Morgan-Giles, who as a veteran of the war in the Mediterranean when they were operating there likely had plenty of opportunities to observe them, said it best: ‘What lovely ships those Abdiels were.’5 Captain John S Cowie, who had a hand in the 1935 memorandum that eventually led to their construction, referred to them as ‘these beautiful little ships’. Samuel Elliot Morison, the official American naval historian of the Second World War, described the Ariadne as ‘handsome’.6

A profile of the 1938 Fast Minelayer design. (Eric Leon)

The Abdiels had a raked stem and a cruiser stern and were flush-decked, with the sheer line of the upper deck running straight most of their length but then rising gently from the bridge to the stem. Their bridge was much more like a destroyer’s than a cruiser’s. They shipped a tripod foremast aft of the bridge and forward of the first funnel and a shorter tripod mainmast aft of the third funnel, with both masts upright, not raked. The two twin 4in gun mounts forward and the single one aft gave their appearance a certain balance and a look of truculence.

One of the most distinctive features of the class was their three funnels, of almost equal height, the middle one larger in cross-section than the first and third ones. The fore funnel was 46ft 8in above the waterline. In having three funnels, they were unique among warships built during the Second World War.

The Abdiels’ twin 4in (102mm) Mk XVI guns were in shielded Mk XIX mounts. They fired a 67lb fixed round with a firing cycle of five seconds. The guns were 45 calibres long, i.e. 45 × 4in, and could elevate to 80° and could depress to 10° below the horizontal.7 The Abdiels were to carry 250 rounds per gun for their 4in guns.8 In spite of reports to the contrary, which began at least as early as the 1941 edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships and persisted for decades, the Abdiels never, ever, carried 4.7in guns.

The disposition of the 4in guns enabled the Abdiels to ship a Mk M (or Mk VII) four-barrel, 2pdr (40mm) pom-pom mount to be placed on a bandstand aft of the third funnel with excellent arcs of fire, instead of between the second and third funnels with much poorer ones. The pompoms had barrels 39 calibres long, with elevation of 80° and a rate of fire of about 100 rounds per minute per gun. The projectile weighed 1.684lb. – not 2lb – and the entire fixed round weighed 3lb. The Abdiels were to carry 1800 rounds per barrel. The ships were designed so that the four-barrel pom-pom could later be replaced by an eight-barrel pom-pom, but this was never done.

The Abdiel s’ gun armament also included two quadruple Mk III .5in (12.7mm) Vickers machine guns, which were fitted in the port and starboard bridge wings and for which the Abdiels carried 2500 rounds per barrel. The Vickers machine guns were soon replaced or at least supplemented by up to seven single-mounted, Swiss-designed 20mm Oerlikon cannon, a much better weapon with a slower rate of fire (465–480rpm vs. 650–700rpm) but a much heavier HE shell, weighing 0.272lb (vs. 1.326 oz. for the .5in gun). The Vickers machine gun was 62.2 calibres in length and the Oerlikon cannon was 70 calibres in length, which resulted in a higher muzzle velocity.9 The Abdiels were to carry 2400 rounds per gun for the Oerlikons.

As for fire control and ‘sensors’, the Abdiels’ 4in guns were controlled by a Mk III director, or High Angle Control System (HACS), sited aft of the bridge, which was equipped with a rangefinder and a Type 285 radar aerial. The pom-pom was controlled by a Mk III director that was sited just forward of the mount. Neither director was optimal. The Vickers machine guns and later the Oerlikons had to make do with local control. The initial four ships sported a Type 286 radar aerial on the foremast, and were equipped with a Type 128 Asdic – now called sonar – for detecting submarines and a DF coil forward of the wheelhouse.

Last but surely not least, the Abdiel s’ armament naturally included an outfit of mines. At first, they were designed to carry 100 mines, but the number was fortunately increased to 150 and in practice they could carry a maximum of 160. The mines were loaded through four hatches in the upper deck and were stowed on tracks in a completely enclosed mining deck that ran much of their length. The mines were disgorged through two mining doors at the stern. The fast minelayers were fitted with the ‘chain conveyor’ system for moving the mines around and laying them, with the older ‘wire and bogie’ system as a backup.

A profile of the final design of the Abdiel class. (Eric Leon)

To facilitate their minelaying operations, the Abdiels were equipped with taut wire measuring gear, which fulfilled the very important function of allowing the positions of their minefields to be assessed with greater accuracy. The gear was first designed for ships laying submarine telegraph cables and consisted of ‘in simple terms a long length of piano wire paid out astern of the minelayer, the amount of wire run off being measured with a high degree of accuracy and recorded on a form of cyclometer’.10 It would prove to be a vital tool for the fast minelayers, when it worked.

The Abdiels’ capacious mining deck was a salient feature of the ships, designed for mines weighing 1¼ tons to run on a ‘Clapham Junction’ network of rails. The ships were equipped with two large cranes, one to port and another to starboard. A post-war history of the Navy’s Construction Department recognised that the fast minelayers were often used for carrying stores and naively claimed that the stores carried on the mining deck were limited to 200 tons.11 That may have been the official policy, but someone must have neglected to tell the Construction Department that in practice the Abdiels carried at much as 373 tons of stores and equipment on the mining deck.12

The ships were unarmoured, with only 10lb protective plating on the bridge. Their hulls were too small for any special protection against torpedoes, other than their normal compartmentation, which unfortunately featured fairly large machinery spaces prone to flooding over a large area with a single torpedo. In hindsight, the bigger problem was their large, undivided mining deck, which did not improve their chances of survival in the event of flooding.

The Abdiel s’ accommodation was to be that of a cruiser or above and their designed complement was twelve officers and 224 men; in practice they accommodated more, by one count 260.13 They were also capable of carrying many passengers and sometimes carried ‘special’ ones, such as brass hats, wounded men and POWs. Their designed complement of boats included a 25ft motor cutter and a 14ft sailing dinghy to port, a 27ft whaler and a 25ft motor boat to starboard, and a 16ft planing dinghy atop the after deckhouse.

The heart of the design of the fast minelayers was, naturally, their machinery. The design provided for four boilers with a working pressure of 300lb/sq. in. at 200° F superheat, divided between two boiler rooms, No 1 forward of No 2, with one boiler in each compartment trunked into the middle funnel. They sported two sets of single-reduction geared turbines – high-power, low-power and cruising turbines – in a single engine room, with the associated gearing in a gearing room immediately aft of the engine room. The turbines drove two shafts and two propellers, each of which had a diameter of 11½ft. Each boiler was designed to develop 18,000 SHP at 350 revolutions per minute, for a total of 72,000 SHP, exactly double that of the Abdiel of the First World War and more than any destroyer in the Royal Navy at the time; the ‘Tribal’ class destroyers developed 44,000 SHP.14 The Abdiels’ designed maximum speed was 39.5 knots at 350 revolutions.

However, the Abdiel s’ true maximum speed soon became the stuff of exaggeration, if not legend. One former crewman claimed with complete earnestness and sincerity to have been shown his ship was making 50 knots. The controversy over their true speed has persisted at least as late as 2012, in the pages of the Navy News, where a claimed speed of 44 knots prompted some spirited debate. The fact is that while the Abdiels were very fast ships, they could not defy the laws of physics. Their design was original but not obviously innovative, especially since they lacked a secret such as superheated boilers; they simply packed very powerful machinery into a small hull with just two shafts and propellers. If there was secret to their speed, it was that they packed more power on each shaft (36,000 SHP) than any other British warship15 besides the battlecruiser Hood, which was also designed to develop 36,000 horsepower on each of her (four) shafts.16

In any case, they were without a doubt the fastest ships in the Royal Navy and may have made just over 40 knots. The Welshman made 37.6 knots on trials,17 and on her trials the Manxman made 35.6 knots while developing 73,000 SHP.18 After her refit in 1942, the Abdiel made 38.6 knots, according to her Navigator, Lieutenant Alastair Robertson, who took great care to measure her speed. For the sake of comparison, the highest speed a major British warship ever made on trials was the 39.4 knots made by the Yarrow ‘S’ class destroyer HMS Tyrian in 1919, though she was in a light condition and with ‘very highly stressed machinery’. In service, she could probably make 36 knots with a clean bottom.19

More importantly, again and again the Abdiels proved that they could maintain high speed in real sea conditions. Almost as important, they could do so without excessive vibration, which would have hindered their effectiveness. A downside to great speed was that, at least early in the Abdiel’s first commission, it led to cavitation, erosion of the base of the propellers. The propellers had to be replaced, but for a time she had to limit her speed to 25 knots.20

The Abdiels were faster than any ship in the US Navy and were equalled or outstripped by very few ships of other navies. For speed, the Abdiel s’ competitors were the six French super-destroyers of the Fantasque class (2569 tons, up to 45.02 knots on trials), the French super-destroyers Volta and Mogador (2994 tons, up to 43.78 knots on trials),21 the Italian-built Soviet destroyer leader Tashkent (2893 tons, rated at 110,000 SHP and 42 knots),22 the three Italian small light cruisers of the ‘Capitani Romani’ class (3747 tons, up to more than 43 knots),23 and the Japanese large destroyer Shimakaze, which was about the size of an Abdiel, at 2567 tons, and made as much as 40.7 knots at 79,240 SHP during her short life, but she also sported boilers that operated at an extremely high temperature (400° C) and pressure (571 psi).24 Not to take away anything from these ships, but they were not nearly as versatile as an Abdiel, though the Tashkent was used a fast transport during the siege of Sevastopol in 194225 before she was damaged at sea and then sunk at the quayside by German dive bombers.

The speed of the Abdiels was one thing, but their endurance was a very different matter. The Abdiels were designed to store 591 tons of oil fuel and 58 tons of diesel fuel, which was primarily for their generators but could be used in the boilers as well. They were to have an endurance of 5300 to 5500 miles at 15 knots when six months out of dock (and with a correspondingly barnacled bottom), but it was estimated from their sea trials that their endurance was only 4680 miles under those conditions. With a clean bottom, their endurance was estimated at 5810 miles.26 In 1942, based on experience with the Manxman, the Admiralty estimated their endurance as 3300 miles at 20 knots, 2070 miles at 25 knots, 1450 miles at 30 knots, 1060 miles at 35 knots and only 845 miles at their maximum speed of 38 knots.27

The Abdiel s’ limited endurance was to become a real concern and was the Achilles’ heel of the design. This unfortunate trait was to some extent rectified in the Repeat Abdiel s. In not living up to their designed endurance, the Abdiels were hardly unique among British warships of the Second World War; according to a Royal Navy study, British warships entered the war with machinery that was 25 per cent less economical than that used in the US Navy.28 Another class that disappointed in this regard was no less than the King George V class battleships. Their fuel consumption under trials conditions was 2.4tons/hr at 10 knots, but in practice it was 6.5 tons/hr, due to heavy consumption by auxiliaries and steam leaks. In 1942, it was found that the true endurance of the new American battleship Washington was double that of a KGV.29 During the Bismarck chase, both the King George V and the Prince of Wales barely made port after playing their parts. That the Abdiels were not unique in their disappointing endurance would have been little comfort.

When the Abdiels were designed, there was nothing like them. And there was never anything like them. Before and during the Second World War, a number of navies constructed purpose-built minelayers with enclosed mine decks, but none of them could exceed 21 knots. The US Navy’s sole representative was the USS Terror, which on a displacement of 5875 tons was armed with four 5in guns and could carry a whopping 900 mines, but could not make more than 18 knots.30 Similarly, the Imperial Japanese Navy built the Tsuguru, Itsukushima and Okinoshima,31 the Polish Navy the Gryf, the Royal Norwegian Navy the Olav Tryggvason, the Spanish Navy the Jupiter, Marte, Neptuno and Vulcano and the Soviet Navy the Marti, actually the former Imperial Russian yacht Shtandart.32 The Royal Netherlands Navy built a number of small, slow minelayers, the newest being the Jan van Brakel and the Willem Van de Zaan.

The originators of the fast cruiser-minelayer, the Germans built two minelayers before the war, the Brummer and the Bremse. The Bremse could even make 27 knots, but they were not the equal of their Great War namesakes. Just before the war broke out, the Germans did design a class of purpose–built minelayers, the first being known to history as just ‘Minenschiff A’. The design provided for a ship of 5800 tons, 4.1in and 37mm guns and enclosed minedecks with a capacity of 400 mines. With a speed of only 28 knots, however, they did not quite qualify as fast minelayers and in any event their construction was not pursued.33

The closest analogue to the Abdiels was the French cruiser-minelayer Pluton, later renamed La Tour d’Auvergne, which was launched in 1929. She carried four 5.5in guns and 290 mines on a semi-enclosed mine deck and was rated at 30 knots. She was lost to an accidental explosion of her mines at Casablanca on 13 September 1939,34 and so never had the chance to prove her worth.

Not that an effective offensive minelayer had to have an enclosed mine deck or carry many mines. The Italian Regia Marina employed light cruisers and destroyers for minelaying and on 3 June 1941, a force of five light cruisers and seven destroyers laid two fields northeast of Tripoli.35 The effort bore fruit more than six months later, on 19 December, when the Royal Navy’s Force K ran across one of the fields and lost the light cruiser Neptune and the destroyer Kandahar. The German Kriegsmarine used destroyers to carry out a daring and highly effective offensive minelaying campaign off the British coast in the winter of 1939–40. In this effort, German destroyers undertook eleven missions, all undetected by the British and laid 1800 mines, which resulted in the sinking of three British destroyers, sixty-seven merchant ships totalling 238,467 tons and other vessels.36

While some other navies employed fast cruisers or destroyers for offensive minelaying duties, none of them was as fast in real conditions, none of them had an enclosed mine deck, none could carry the mineload of the Abdiels and none was as versatile. The Abdiels were not the only game in town in offensive minelaying, but they were truly unique and were no doubt the best.

Once the design of the Abdiels was finalised, the first three fast minelayers, the Abdiel, Latona and Manxman, were ordered in December 1938 as part of the 1938 shipbuilding programme. A fourth ship, the Welshman, was approved at the November 1938 Cabinet meeting as part of the 1939 programme, but she was not actually ordered until March 1939.37 The first two fast minelayers were named after minelayers that served in the First World War,38 but the Manxman and the Welshman would be exceptions to the rule.