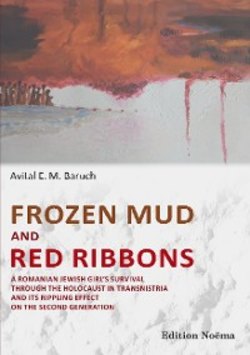

Читать книгу Frozen Mud and Red Ribbons - Avital Baruch - Страница 12

Chapter One Spring 1935: From Mihaileni to Iasi

Оглавление“Had I been asked to speak of it, I would have begun with the story of the generation that raised me, which is the only place to begin. If you want to understand any woman you must first ask about her mother and then listen carefully... The more a daughter knows the details of her mother's life...

the stronger the daughter.”

Anita Diamant, ‘The Red Tent’

Le-Chaim means ‘to life’ in Hebrew. It’s what you say when you celebrate and ‘toast’ your wine glasses together. Chaim is ‘life’, and it was my grandfather’s name. His surname was also Chaim. But this duality wasn’t in his favour, as he didn’t enjoy too much life and was destined to die a most horrible death at the age of thirty-three.

You might call it coincidence, but my grandmother happened to be called Chaya, meaning ‘she who is alive’. In her case, the name brought a bit of luck, so she was spared, and lived long after him. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have been here to tell you their story, as the backdrop to the stage on which my mother’s play of life took place.

My grandmother, Chaya, was born in Mihaileni, a very small town in Northwest Romania. Her parents, Avraham and Gitté, came from Transylvania. Gitté was born in Czernowitz, a famous city in the old Austro-Hungarian kingdom, where the language was a melange of German, Romanian, and Hungarian. Gitté probably didn’t have a formal maiden surname and as was the custom in those days, until around the mid-nineteenth century, she was called Gitté-daughter-of-Yerachmiel.

Their ancestors were descendants of the Jewish people who were exiled from Spain in 1492, wandered around eastern Europe, into the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and found their way into villages in Romania in the 18th and 19th century. They lived in the high street of Mihaileni, where most of the other Jews lived. There, in one road, were nine synagogues, a Mikveh[2], a Jewish primary school, and at the far end, at the top of the hill, the Jewish cemetery. It was a jolly, very lively market town, with a well in the middle of the main road, being a centre for meetings and gossip. The Molnitza River, a tributary of the more well-known Siret River, was winding merrily through the town, and a beautiful forest was resting by its border, beyond the houses and the fields. There was a diverse social make up of people in that tiny village, all living together in exceptional harmony, with mutual respect. The Goyim[3] were generally more well off and most of them lived on the hill above the ‘village’. They usually owned some land and farms and brought their merchandise to the Jewish workshops every morning: milk, cheese, wool, and anything on the farm that needed fixing.

Mihaileni was on the border between Bessarabia and Bukovina regions. Before the First World War, Bessarabia belonged to Russia and Bukovina belonged to Austria-Hungary, but after it, both Bessarabia and Bukovina were annexed to Romania. When the town was founded in the end of the Eighteenth Century, only Jews from Bessarabia or Bukovina were permitted to settle there. Jewish merchants were exempt from paying taxes for the first year, to attract them to the area. In 1834, Mihaileni became the property of the prince of Moldova, who granted Jewish merchants further privileges, exempting them from taxes for five years and granting them loans. Exactly a hundred years later, the descendants of these traders were not permitted to get any credit or trade in the free market, due to new regulations of these same authorities.

In 1859 there were 2,472 Jews in Mihaileni, making up two thirds of the total population, most of them merchants, especially fur traders and manufacturers of wagons who supplied to the whole of the Moldova region. It became a centre of Yiddish and Hebrew culture. Even the Goyim could converse in Yiddish, being in strong trading and neighbourly relations with the Jews. In 1930, the Jewish Party obtained a majority in the municipal council elections, but then the election results were obliterated by the authorities. In 1940, when Bessarabia was annexed to the USSR, a group of Jews in Mihaileni were accused of treason and spying for the Russians and were consequently arrested by the Romanian authorities. After another year of threats, in June 1941, Mihaileni’s Jews were deported. Three years later, half of them were dead.

In history books they use the word deported, so I follow suit, but deported is a word commonly used for foreigners who need to leave a country that they entered illegally. The real word to describe the act of the authorities should have been exiled, or rather, thrown out, in my opinion, because the Jews were ordered to leave their legally owned homes and houses.

Each synagogue in Mihaileni was lead by a different rabbi and was a centre of a separate congregation usually divided according to their trade, occupation, or origin. My great-grandfather Avraham’s family belonged to a synagogue nicknamed Ingerishé (Yiddish for ‘the hungry people’), or in short: the Ingers. They used to pray so fast that people were joking and saying: “These Blacksmiths are so Ingeric. They are in a rush to go home for dinner.” In fact, I think that people were jealous at their genius and ability to read fast. Anyway, the story goes that when the time came to register with an official family name, they transformed their ‘nickname’ into the common Romanian name: Ungureanu. A nice story, but not necessarily authentic. Jews tended to adopt Romanian names as a means of belonging to Romanian society. Also, most likely, traders of all religions who used to travel to Hungary on business were given this name. I wouldn’t be surprised to find out that the story about the hungry blacksmiths was born after they were already called Ungureanu. In any case, Chaya’s maiden name was Ungureanu, and in short, Ungar. It wasn’t such a great honour to be called Ungureanu in Romania; Hungary was not considered an ally, to say the least.

The houses in Mihaileni had thatched roofs with round stocky chimneys, and windows that opened to the street, with wooden shutters to protect from the heavy snow in winter and from the scorching heat of summer. The Jewish families in Mihaileni usually lived in the flat above their workshop. M