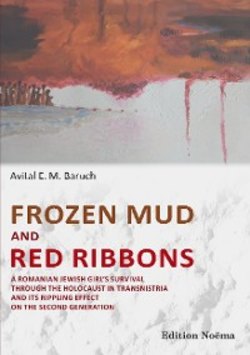

Читать книгу Frozen Mud and Red Ribbons - Avital Baruch - Страница 7

Introduction

ОглавлениеMy mother had managed brilliantly to sweep her past under the carpet, concealing the fact that she had been in anything equivalent to a Nazi concentration camp during the Second World War. I knew that her family was exiled from Romania to Ukraine, that they had starved there, that they didn’t always have a roof over their heads, that it was freezing cold, and that her sister and her father died. What I did not know was that she had experienced the Romanian’s version of concentration camps. The Romanian’s Holocaust.

At school, in history lessons, we learnt about persecution, deportations, and concentration camps in Poland, Germany, Austria, Holland, France, Hungary, but there was never any mention of a place named Transnistria. I thought for a time that it was a secret word that only my grandmother and a few of her backanté (Yiddish for acquaintances) knew. In some ways it was a mystery mission, a quest, for me to find out about that secret place. Two years after learning to read, being eight years old, I had already started to comb our local library, in the suburbs of Haifa, and devoured every single book written by people who had experienced the Holocaust. I felt compelled to reveal what seemed to be an awful big secret, but I couldn’t find any mention of that place, or any clue about my own mother’s past. Her childhood whereabouts, as well as any details concerning her father’s side of the family, remained a black hole for me. By this I mean it was not only an unknown mystery, but, like a black hole in the cosmos, it sucked a lot of my emotional energy into it.

When my mother’s feet touched the Holy Land at the age of sixteen, she stood upright, looked up to the sky and said: “Now I start a new life”, and since then tried to forget the past. In smartphone terms you might say: “She put her past on silence, or discreet, not to distract her from the here and now.” Yet, so often an event occurred that cracked that wall of silence. I remember standing outside with a ‘Sab-re’ neighbour, a woman of my mother’s age who was born and brought up in Israel. They were talking about a film on the Second World War. Rinna, the neighbour, commented on how horrible its portrayal was in the film. My mother gave her a cranky look and said: “This film makes it appear too beautiful, this is Hollywood; the reality was far worse, with no comparison at all.” Some days later my mother said to me out of the blue: “I could also write a book about what I went through.” Her words and her attitude were factual, straightforward, without emotion. The seed for this book was probably planted on that very day.

I always experienced my mother as very resilient, like a rock which will withstand any difficulty on earth. Once, when I had a tummy upset she muttered: “My stomach will not get upset even if I would feed it stones.” On the other hand, there was a more vulnerable side to her which I never encountered personally. If I happened to quarrel with my mother during my adolescence and we both became upset and moody, my father used to come to my room and talk with me for hours to restore the peace. He used to be, and still is, a real peacemaker, smoothing away conflicts; he would never let me go to sleep upset. On those occasions he would say: “Please forgive your mother, please try not to annoy her, she has suffered enough, she still wakes up at night with nightmares.” My heart would melt a little towards her, as I saw her in a different light for a second. So I forgave, but inherited having regular nightmares.

The first one I remember is of a wolf coming to visit me in the night and standing near my bed, staring at me. Following my screams, my father came to my room and assured me that he had sent the wolf away. “There”, he would say, as he waved his muscular arm in the air, “It’s gone.” I could still see the wolf staring at me, but my strong father nearby made it look tame. As I grew up the nightmares kept changing: there were lots of episodes of shooting, hiding, and running away from the Nazis. At a later stage of my life, the theme transformed further, from falling off staircases without banisters to trying to find food and shelter for my family, with the Nazis threatening to invade the town.

Now, after writing the whole story as my mother had told it to me, after conducting research in Holocaust museum libraries, and after reading testimonies of other survivors of the same places, I know that the reality was indeed much worse, and no words could do it any justice. So, I came to a certain conclusion about the matter. I decided I have no interest in analysing whose ‘fortune’ was worse, or what story is the most devastating. I started searching in my soul to try and discover for myself why it is so important for me to write this book, and why I think that although my mother kept distracting me from the ‘job’, it was of benefit to her too.

One conclusion of my search told me that it is all about cleanliness. I feel and believe that cleaning and tidying your house brings you peace of mind. It is easier to start working on a new project when your desk is clear. Therefore, when writing down all the mess from within, clearing all the disturbing memories out, organising and cataloguing them, we give the past its recognition, and our ancestors their honour. We clear our mind in order to be free to work on our own task in life.

My mother asserts that in order to be active, take part in the building of the new country, raise a family, be sane and normal, she had to forget the past and put it aside. I wish she had been given the chance to write it or record it somehow before ‘opening a new page’ of her life. If only she had been able to clean up a bit before I was born into that new page; before I came and experienced shadows of script from previous pages without knowing what they mean. Well, it was not an option at the time, since no one was concerned then with psychological issues. People wanted to live in the present and make plans for the future, and not dwell on the past. Since my mother never had the opportunity to record her experiences in any way, and since the painful memories rubbed off onto me too and fed into my soul, I feel responsible to write it all down. I do it for both of us, as well as for other survivors and their offspring, for the ones who perished and for anyone who is interested in people’s struggles and biographies. And beyond this, it is a story of a generation, of a culture, of a time which was, and will never return.

In a talk by Lord Jonathan Sacks, the former UK Chief Rabbi, about fertility treatments and maternal identity, the question arose: “Who is the real mother, the genetic one or the one who carries the baby in her womb?” There are two opposing views about it by two great Jewish scholars[1]. So, I asked myself, in the case of me giving birth to this book, which is mainly my mother’s story: “Is she the genetic mother and am I the surrogate mother?” I am my mother’s daughter, yet her life story became my baby.

I have asked my mother thousands of questions. Her answers were initially too short and factual, and then became convoluted, moving backwards and forwards in time. I took notes in Hebrew and Yiddish, as she narrated her story; I sorted them out chronologically and according to characters, trying to make sense of it all. I came back with more questions, trying different angles when I sensed that she was inclined to ‘close the door’, and finally re-wrote the Hebrew notes into an English narrative, so my children can read it. Ideally, my mother’s story should have been written in Yiddish—being the language of her childhood—but my Yiddish skills are not sufficiently honed. I have found it important to retain some phrases in Yiddish and in Hebrew; and at other times I translated, trying, as far as possible, to be true to the real ‘pulse’ of the characters.

My mother’s story is one amongst myriads of survival stories. Each single story not only represents another individual, but induces a different atmosphere, depending on the angle of the spotlight from which the author is observing it. We may cope with similar challenges in life, but we do it in our own unique way, ending up with diverse stories to tell. All survivors of the Holocaust became soul-damaged in one way or another. Some ‘utilized’ their pain in artistic ways and became famous painters, writers, and even, ironically, comedians. Other survivors could merely manage to keep up with being like everyone else, carrying their grief inside and their grumpiness as their daily expression, telling themselves that every extra day they are alive is a victory over those responsible for the shift in the script of their life.

We are born into a script, which we are obliged to follow. When we are forced off our script by external events (such as being evicted from our home at the age of six), we can take advantage of it, like surfing on a dangerous wave, and come back safely to the shore, standing upright and happy on the surf-board; or we can be swallowed by the wave, and even after surviving it, remain resentful for the rest of our lives. Everyone reacts differently to being forced off their script. There are no right or wrong reactions; rather there is instead a range of stories to tell.

However, I am probably explaining myself too much again. Perhaps ‘excessive amplification’ should be added to the symptoms of ‘The Second Generation of the Holocaust Syndrome’.