Читать книгу Zero Days - Barbara Egbert - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

IN THE BEGINNING

Day 3: Today was not all that interesting. We walked through a burned area and walked 16 miles.

—from Scrambler’s journal

JUST NORTH OF KITCHEN CREEK, 30-some trail miles from the Mexican border, the Pacific Crest Trail crosses a clearing near a campground. A small PCT marker guides thru-hikers on their way north; a side trail to the left leads down to a dirt road. As Mary, Gary, and I entered the clearing through tall, fire-scorched brush on a warm April morning, a woman wearing a bright red shirt watched us curiously. She and her husband and their two children—boys about 7 or 8 years old—had walked up the small hill to the trail intersection.

“Hello,” Mary greeted the young mother as we approached. Always friendly, Mary is eager to socialize with everyone she meets. “Hello,” the woman responded. “Where are you going?”

Mary pointed to the trail sign: “We’re hiking the PCT.” The woman had obviously never heard of the PCT, and she looked at me with the quizzical expression of an adult confronted with a completely nonsensical statement from a child. “We’re hiking the Pacific Crest Trail,” Gary explained. “It goes from the Mexican border to Canada, 2,650 miles. We’re on our third day.”

At this point, the woman’s expression changed to something between disbelief and fear. I assured her we were sincere. She looked at her husband and children, then at Gary and me, with our sweaty faces, big packs, and little kid in tow. “You’re kidding,” she said. Then she said it again, “You’re kidding.’’ Finally, she turned to Mary and exclaimed, “You’re not going to let them make you do this, are you?” Mary folded her arms, stuck out her chin, and replied, “They’re not leaving me behind!”

As the magnitude of our endeavor sank in, I could picture what was going through this woman’s mind. A hike of the Pacific Crest Trail is an impressive feat, especially for a child. Beginning in southern California’s Mojave Desert at a modest monument near the wall along the southern border of the United States, the Pacific Crest Trail runs from Mexico to Canada, ending at a matching monument on the northern border, at the edge of British Columbia’s Manning Provincial Park. Along the way, the trail rises and falls through the San Jacinto, San Bernardino, and San Gabriel ranges (and the desert valleys in between) before ascending to the crest of the Sierra Nevada. Its highest point, at 13,180 feet above sea level, is at Forester Pass in the southern Sierra. Continuing north over a succession of lofty mountain passes through Sequoia, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite national parks, the trail takes in views of Lake Tahoe in central California and then winds its way north through the mountains toward Lassen Volcanic National Park in northern California. Following the crest of the Cascade Range, the PCT offers views of Mt. Shasta before continuing into Oregon and Washington on a route punctuated by more volcanoes, including Mt. Jefferson, Mt. Hood, Mt. Adams, the still-smoking Mount St. Helens, and the mighty Mt. Rainier. At the Canadian border, as if ushering jubilant hikers back to civilization, there is a broad, 7-mile trail to the nearest paved road.

The PCT zigzags along ridgelines, meanders through public property, and follows wandering rights-of-way across private lands. The trail is more than twice the length of the highways that travel the same route from south to north; indeed, if you wanted to drive a distance equivalent to the trail, you would have to take your car from Los Angeles to Baltimore. Because of its length, PCT thru-hikers typically allow five to six months to hike the entire distance. Our own PCT adventure lasted from April 8 to October 25, 2004.

It’s not surprising that most people who encountered our threesome reacted with disbelief. Even if they had heard of the trail—and many had not—it’s rare to see a pair of 50-something parents and their 10-year-old cheerily saddled up with big packs for the trip. The people least likely to believe we could do it—much less would want to do it—were adults engaged in a weekend camping trip, complete with RV, generator, running water, and television set. It’s hard enough explaining to sympathetic friends and relatives why we would want to spend an extended vacation lugging heavy loads up steep hills, sleeping on the ground, and digging holes for trailside latrines. But parents whose children have to be cajoled to move more than a few feet away from their video games cannot imagine a 10-year-old girl who can walk 20 miles a day with a full pack, and get into camp still capable of climbing trees and making up games with twigs and pinecones.

We found ourselves constantly responding to the kinds of questions that dayhikers and car campers are prone to ask upon meeting a trio of hard-muscled, razor-thin, scruffy-looking hikers intent on racking up a 20-mile day: How do you get food? How often do you take a shower? How come your daughter’s not in school? But the biggest question everyone asks, which is even more important than how much weight has been lost and how many bears have been seen: Why are you doing this?

THE STORY OF WHY we attempted to hike the Pacific Crest Trail as a family—and in the process gave Mary an opportunity to become the youngest person to finish—begins even before Gary and I met. While I spent my childhood exploring the high desert and lonely mountains of east-central Nevada, Gary was rambling around rural Maryland, 2,000 miles to the east. We both grew up comfortable in the wilderness and felt a strong need to escape into it frequently. We were in our 30s when we met in the spring of 1988. I was living in Baltimore doing a year of volunteer work, and because I had no car, I jumped at a friend’s offer to join a hike and get out of the hot, humid city. That’s where I met Gary, along the banks of the Gunpowder River. Soon, he invited me on our first date; rock climbing at Annapolis Rocks, along the Appalachian Trail in Maryland, I learned how to belay with no difficulty, but when it was time for me to rope up and ascend a fairly easy climb, I froze. I was maybe 6 feet off the ground and I panicked. Couldn’t move up, down, or sideways. Gary had to coax me down like a police negotiator talking a desperate stockbroker off a 20th-story ledge. To my surprise, Gary invited me on a second date, my very first backpacking experience. We hiked into Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park on a Friday evening, and I thought I would collapse from the heat and humidity. But otherwise it was wonderful, and I discovered that I loved backpacking as a novice just as much as Gary did, with his 20 years of experience.

Gary drove out to California the next year so that we could get married. The bridegroom’s present to the bride: Hi-Tec hiking boots (still my favorite brand) and a pair of convertible pants—the kind with zippers around the legs that allow you to change them from trousers to shorts without taking off your boots. We took care of the important stuff first—a pre-nuptial trip to the Grand Canyon—and after that dealt with such minor details as meeting with the minister, purchasing the wedding rings, and inviting guests to our outdoor ceremony.

By the time Mary was born four years later, Gary and I were a bona fide backpacking couple, and we knew we would include Mary in the backcountry outings that were our chief form of recreation. She was only two months old on the first trip, to Manzanita Point in Henry Coe State Park, southeast of San Jose. It was a sunny January day, and I carried Mary in a sling, while Gary heaved about 90 pounds—including Mary’s infant car seat—the few miles from park headquarters to our campsite. Except for Gary’s enormous load, it was an easy trip with mild weather, only a few miles to walk, and a spacious campsite with a picnic table. I was breast-feeding and we used disposable diapers, so feeding and diapering were simple. We divided tasks so that Gary took care of our camping chores, setting up the tent, arranging the bedding, and making dinner, while I looked after Mary’s needs.

Nonetheless, I was nervous those first few trips taking our baby into the wilderness. I couldn’t sleep because I was so worried about how Mary would fare on those chilly nights in the tent. Infants can’t regulate their body temperatures as well as adults, and they don’t wake up and cry when they get cold, as older children will. They can quietly slip into hypothermia. I arranged Mary as warmly and comfortably as possible in the car seat, inside our four-person dome tent. Then I crawled into my own sleeping bag next to her. I would check her every few minutes to make sure she was warm enough. If I didn’t think she was, I’d take her into my bag to warm up. I didn’t dare fall asleep, for fear of rolling over on her. Every couple hours, she would cry and I would nurse her.

Some of the adjustments we made for family backpacking trips would occur to any experienced parent: Allow extra time for camp chores, and venture out only during good weather. But I quickly learned other tricks, like trying to schedule our trips during a full moon, which made it easier to discern the outlines of baby, blankets, and diaper bag in our dark tent. Some things we learned the hard way. During a particularly inconvenient phase in our backpacking history, Mary was throwing up—a lot—and it was then that we discovered the importance of sealing everything that is wet, or could possibly get wet, inside two Ziploc bags. I even got the hang of breast-feeding while walking. This was an invention born of necessity: We were hiking near our home to a backpackers’ site in the Sunol Regional Wilderness, and a steep hill lay ahead of us, when Mary made it clear she needed to be fed. But if I stopped for 20 or 30 minutes, darkness would overtake us before we reached the top. I stopped long enough to let her latch on, arranged the sling around her securely, and carefully resumed walking. To my surprise, the motion didn’t bother her, and we reached our destination in plenty of time, with a happy, well-fed baby to boot.

At six months, Mary moved into a Tough Traveler “Stallion” model baby backpack, with all the options: a rain hood with a clear plastic window, side pockets, and an extra clip-on pouch. Mary frequently fell asleep in the backpack. Her little head would rest against the pack’s coarsely textured fabric, and she would develop a rash there. So we padded those parts with flannel from an old nightgown. We also made a two-part rain cover out of waterproof, ripstop nylon, with Velcro to hold the two parts together. On clear days, we used diaper pins to clip together receiving blankets or old crib sheets to ward off the sun. I also bought a little round rearview mirror from an auto-supply store that I used to check on Mary when she was on my back. You wouldn’t think a small child could get into trouble in a baby backpack, but during a trip to northern California’s Lost Coast, she managed to pull some leaves off a tree and stuff them in her mouth. Another time, while we were returning from the summit of Utah’s highest mountain, 13,528-foot King’s Peak, she somehow managed to squirm around until she was riding sidesaddle.

By the time Mary was 1 year old, we had taken her backpacking six times, and to celebrate her first birthday, we took her on a trip down the New Hance Trail off the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. Each year, we kept hiking and backpacking as a family, tailoring the trips to Mary’s needs and abilities, but always challenging ourselves to do more. Back then, there were few books on backpacking with children, and the few in print suggested that it just couldn’t be done at certain ages. We never found that age. If Mary couldn’t walk the entire distance, I would carry her part of the way. If she wanted to walk but was getting tired, I would entertain her with endless stories to keep her mind off her problems. On our trip to the Grand Canyon, we hit bad weather as we were hiking out. We had swathed the pack with our home-sewn rain cover, but this meant Mary couldn’t see out the plastic window in the hood. And she got bored. I sang. I told stories. And then Gary hit on the perfect boredom reliever: raspberry sounds. One of us would make a loud noise, blowing out with our lips flapping, holding it as long as we could, and then the next would try to top it. This got us all laughing, and eventually we made it back to the trailhead.

As Mary got older, we discovered that dehydration was the surest source of trouble, and that crankiness was the surest sign of dehydration. Whenever Mary complained about the heat or the distance, or sat down in the trail and refused to move, we’d have her drink a cup of water. If it was late in the day and Mary was getting too cold or sleepy, we’d start looking for a place to set up camp. Just knowing she wouldn’t be forced beyond her limits, or criticized for weakness, helped Mary enjoy backpacking when she was small. By the time Mary was in kindergarten, she could easily hike 10 or 12 miles at a stretch, climb Mission Peak (the 2,517-foot hill that dominates the skyline around our home in Sunol), and help with camp chores.

Although Mary, Gary, and I don’t remember exactly whose idea it was to hike the Pacific Crest Trail as a family, I can trace the genesis of the plan to 1999, when we hiked the 76-mile portion of the PCT that runs from Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite National Park to Sonora Pass. That ambitious expedition was the watershed trip for everything that followed. Mary was five-and-a-half years old when we began planning. Initially, we decided we would take her out of first grade for a week in October and hike what is known as Section J of the Pacific Crest Trail in the central Sierra Nevada. (The PCT is divided into sections of 38 miles to 176 miles, labeled alphabetically from south to north. All of California is divided into sections A through R, and then the alphabet starts over again. Oregon and Washington are divided into sections A through L.) On the map, the 60-mile stretch from Sonora Pass north to Carson Pass looked rugged but not too challenging. Two weeks before our start date, however, I suddenly remembered something I had almost forgotten after 10 years of living in the heavily populated San Francisco Bay Area: hunting season. Gary and I might have risked it anyway, with the help of matching Day-Glo orange vests, but we weren’t about to put Mary in harm’s way. She was a strong hiker, but hardly bulletproof. We hastily rewrote our plans so that we would go south from Sonora Pass instead of north, thus spending most of our trip on National Park Service land, where hunting is prohibited. This change from Section J to Section I also meant a longer and more difficult trip. Gary arranged to change our permit, and I talked my older sister, Carol, into picking us up in Yosemite.

When we reached Smedberg Lake in the Yosemite backcountry’s perfect alpine setting of granite and evergreens, we had been out five days and were 50 miles into the trip. That day, we had walked 12 miles with a total elevation gain of 3,500 feet. Mary was happy as a lark. While Gary filtered water and I set up the tent, she took my bandanna down to the edge of the water and “washed” it over and over. Mary had been in particularly fine form that day, leading us up the initial 1,000-foot hill to Seavey Pass, down 1,590 feet to Benson Lake, and then up 2,500 feet before dropping down to Smedberg Lake.

That’s when we realized that Mary had it in her to tackle a really long hike. This particular section of the PCT is one of the most remote parts of the entire route. The trail doesn’t cross any roads, paved or dirt, for the entire distance. If one of us had suffered sickness, injury, or snakebite, we could have been as many as 38 miles from a road. Most of the eight days we were on the trail, we saw nobody, so we were completely on our own. As it turned out, the Section I trip was a tremendous experience, but not a perfect one. In fact, several things went wrong. What was so encouraging was that we were able to deal with them.

The problems started on our first day. Leaving Sonora Pass in late morning, we ran into trouble after a few miles when the trail headed straight into a steep snowfield that looked too dangerous to climb. We followed footsteps off to the right, marked by rock cairns, but we still ended up on a precarious, unstable slope. We spent a lot of time working our way down through the shattered rock. Mary took a fall and Gary caught her just in time to avoid injury. This delayed us to the point that we were 3 miles away from our intended campsite as darkness fell. We were all very tired, and we had enough water to get through the night, so we set up the tent on the first flat space we found. The next day, we easily made up the 3 miles and got to Lake Harriet by dusk.

Second day, second problem. About half of the rechargeable batteries that should have been enough for the entire trip turned out to be duds. Most backpackers are early risers, but not us. We like to get up in full daylight, hike until dusk, and then set up camp by headlamp. But now we had to change our habits, getting up at the icy crack of dawn each morning and hiking quickly to take advantage of all the light that an October day holds. We wanted to be in bed, not just in camp, by full dark each evening.

Third day, third problem. When we left our campsite at Lake Harriet, we headed up the obvious trail, only to arrive at Cora Lake, most definitely not where we wanted to be. I was tempted to try to cut cross-country at this point, rather than backtracking and wasting all that time and effort. I stared off across the trees, in the general direction of where we should have been, and asked Gary if we could go that way. His response: Definitely not. Cutting cross-country, he explained, sounds simple but is usually a mistake. Unless we could see our goal, plus an easy route to it, we’d be better off going back to our campsite and starting over. Otherwise, we’d probably get off course, or find our route blocked by a drop-off or impassable thickets.

Gary and I are devoted readers of news articles about people who come to grief in the backcountry. Trying to make up for a mistake by cutting cross-country instead of backtracking ranks high on the list of how hikers get into serious—and sometimes fatal—trouble. A few years after our Section I trip, an experienced outdoorsman decided to take a shortcut through California’s Big Sur wilderness in order to shorten his planned two-week, solo backpacking trip. He ended up stranded at the top of a 100-foot waterfall. Fortunately for him, campers below heard him yelling and got help. He had to be plucked from the inaccessible terrain by helicopter. A year earlier, another experienced hiker found himself off the trail in the Sierra Nevada’s Stanislaus National Forest. Rather than retrace his steps, he looked on the map for a shortcut, and thought he had found one in the shape of a dry streambed. The streambed was so rugged and steep, he eventually fell, ending up too badly injured to walk away. He staggered out days later. Gary had a simple rule to follow whenever we were unsure of where we were, whether on trail or off: Go back to where we were certain of our location, and then decide what to do. So it was back to Lake Harriet.

The fourth and fifth days brought only minor problems, like snow and cold. But on one particular day after we were halfway through, we couldn’t seem to get along with each other. At home, we simply would have avoided each other for a while. Unfortunately, this is not a solution in the backcountry. The interactions among groups of people who tackle stressful activities such as long backpacking trips, big wall climbs, and mountaineering expeditions are pretty intense. The stresses can bring people closer together as they learn to value each other’s strengths while becoming more tolerant of each other’s weaknesses. But it’s just as likely—probably more so—that the stresses will tear a group apart, or weaken it to the point that it doesn’t function adequately. We heard tales about couples who broke up on the trail, or even after finishing.

On our seventh day, when we left our frosty campsite at Miller Lake (at 9,550 feet above sea level) and headed for Glen Aulin High Camp, Mary and I were heading down a hill in thick woods a couple hundred feet ahead of Gary. Instead of focusing on the route, I had my mind on my grievances with my husband. I followed what I thought was the main trail, heading off to the right into a meadow. Gary spotted the correct trail, heard our voices, and realized we had gone the wrong way. He shouted for us to stop and to head back toward him. If we had been much farther apart, we might have gone our separate ways for an hour before realizing our mistake. As it was, we all stayed together (however unhappily) until we reached Glen Aulin.

Perhaps what truly foreshadowed our future PCT expedition was the particular stuffed animal Mary had set aside for this trip. We always allowed Mary to bring one stuffed animal on backpacking expeditions, and making the choice was a big deal for her. For this trip, Mary had originally selected a little stuffed porcupine. However, when we arrived at my father’s house in Minden, Nevada, to spend the night before starting, she discovered that my cousin’s son, Andrew, had left her a little stuffed Chihuahua that he had won a few days earlier at the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk. Mary named it “Puffy” and immediately fell madly in love with it. When Carol dropped us off at Sonora Pass next morning, we learned that Mary had brought Puffy along, and wanted to bring both stuffed animals on the trip. At this age, she didn’t carry anything on backpacking trips, and Gary and I refused to add any more weight or bulk to our well-stuffed packs. This nearly precipitated a major argument just as we were ready to begin walking. At the last minute, Mary agreed to leave the porcupine behind and take only the Chihuahua.

Eight days later, we met my sister, Carol, and her husband, George, in Tuolumne Meadows at the end of our trip. As they walked down the trail to greet us, Carol whispered to George, “Get it out of your pocket.” George pulled out the porcupine and, with a shriek of joy, Mary rushed down the trail to retrieve her little friend. Two years later, it was again Puffy who got to accompany Mary on a big trip, the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail (by this point, Mary carried a full pack, including her “animal friend“). But in 2004, the little porcupine finally got his chance. Mary gave him his own trail name, “Cactus,” and carried him on the PCT.

With Section I successfully completed, we began seriously considering a PCT thru-hike. Both Gary and Mary insist it was my idea. (I was willing to take the credit during good days on the trail; on bad days, I was convinced one of them must have come up with such a crazy scheme.) Despite my supposed status as originator of the family thru-hike goal, I had many doubts about whether I could actually do it. When a friend who has known us for several years asked me at a book club dinner, “What will you do when Mary caves?” I assured her I was the weak link in this particular chain. I have always felt somewhat of an impostor among hardcore backpackers. Gary is the most competent person I know in backpacking, rock climbing, and mountaineering. He’s totally at home in the woods. And Mary is well on her way down the path trod by her father’s boots. Even before she set out to conquer the PCT, Mary was the youngest person to summit Mt. Shasta and to thru-hike the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail.

But I look at thru-hikers, especially the women who are strong enough and brave enough to hike long trails alone, and I think, “I could never do that.” I have to remind myself that I am strong and brave and skillful. I lived a full and occasionally adventuresome life on my own before Gary and I married. But sometimes I feel the way I did when I first joined Mensa, the high IQ society. For several weeks after I received the letter announcing I had qualified to join, I was convinced another letter would follow with an apology for their mistake. Months went by before I lost that nervous apprehension every time I checked the mailbox. Eventually, I attended a few Mensa gatherings and discovered I was as brainy as any other member. The same has been true of backpacking. I’ll read a trail journal by some woman who set out by herself when she was 60, or some man who went through the Sierra when every trail marker was buried under 15 feet of snow, and feel totally intimidated. And then I’ll meet those people at the Pacific Crest Trail kickoff or an American Long-Distance Hiking Association conference and realize that, hey, we have a lot in common.

Despite our ambitions, none of us was immune from worrying about whether we could—or should—try to thru-hike the PCT. I fretted about our ability to handle the physical challenges and, like many parents, nervously imagined how I would feel if Mary were to be seriously injured from a fall, bear attack, or lightning strike. Gary worried about the danger of one of us drowning during a stream crossing. He also worried how an independent-minded 10-year-old would behave when faced with day after day of discomfort, hard work, and enforced togetherness, aggravated by inadequate food and rest. Mary, aware of her father’s concern, mostly worried that the trip would be called off at the last minute. Gary was tempted several times to cancel it, but about six months before our projected start date, he made a commitment to go for it, no matter what.

Once we decided to do the trip, computer technology was a huge help in our preparations. Thanks to the internet, we could connect with experienced thru-hikers eager to weigh in on every aspect of the trail experience. Some long-trail veterans have journals online, and many of them are surprisingly personal. Many backpackers and trail fans participate in the PCT-L, an online forum that regularly hosts heated debates on everything from the best type of stove and fuel for long-distance hiking, to whether dogs should be taken on the trail. I conversed via email with a married couple in Pleasanton, California, near our home in Sunol, who completed the PCT in 2000. They were in their early 50s, just like Gary and me when we began. Marcia and Ken Powers went on to complete the Triple Crown: the PCT, the Continental Divide Trail (in 2002), and the Appalachian Trail (in 2003). And in 2005, they achieved the grand slam of long-trail backpacking when they finished the coast-to-coast, 4,900-mile American Discovery Trail. In the same way, I got in touch with a young man in Berkeley who completed the PCT in 1999. I read his online trail journal while he was hiking. After he finished, we exchanged emails with practical discussions about gear. Along with these seasoned backpackers, several trail publications provided essential guidance, most notably the three Pacific Crest Trail guides published by Wilderness Press, plus the accompanying Data Book; the Town Guide, published by the Pacific Crest Trail Association; A Hiker’s Companion, by Karen Berger and Daniel R. Smith, from Countryman Press; and Yogi’s PCT Handbook.

One of the questions they helped to answer was why more people don’t hike in groups. Why do so many start out alone? There are obvious benefits to hiking with at least one other person—safety, companionship, a second opinion on trail options, or a potentially cooler head in a pinch. And some thru-hikers are lucky enough to walk the entire distance with one or two others, usually spouses, sweethearts, or very close friends. But many have to plan for a solo experience. Why? Because hardly anyone wants to do it. In the years leading up to our trip, between 200 and 250 people attempted to hike the PCT each year, according to Greg Hummel, who keeps track of such things as part of his involvement with the American Long-Distance Hiking Association. He estimates that 50 percent of those people had the ability to finish, but only 30 percent to 35 percent actually did. So, something like 65 or 75 people might walk from one border to the other in a typical year. About 300 wannabe thru-hikers began the trail in our year; about 75 finished. The completion rate ranges from 60 percent in an exceptionally good year to about 10 percent for a bad one. Those are guesses, to be sure. No one knows for certain how many people start, how many finish, and how many are completely honest about having hiked the entire distance. By the time they reach Oregon and Washington, many former purists find themselves willing to skip small portions. A hiker might have to spend a few days in a motel room recovering from illness and want to catch up with his trail companions with a little hitchhiking. Or a thru-hiker might get a ride into a town stop, and then the next day someone offers to drop her off a little farther along, perhaps avoiding one of the more unpleasant stretches of trail.

The solo nature of the long-trail experience comes as a surprise to many people. They’ll ask, “You hiked with a group, right?” What they expect to hear is that we signed up with some sort of guided tour, like a Sierra Club outing or an expedition on Mt. Rainier. But the Pacific Crest Trail, just like its sister long trails, the Appalachian Trail and the Continental Divide Trail, provides one of the few major outdoor experiences that is devoid of professional guides. This is a completely amateur undertaking. Now, to be sure, few people hike alone all the time. Those who don’t start out with a partner or spouse tend to form casual groups on the trail, as three or four hikers discover that they move at about the same pace and enjoy each other’s company. These groups are small and fluid, dissolving at town stops, re-forming a few days up the trail. The speed with which thru-hikers find themselves part of a community stems from this lack of hierarchy. There is no one whose job it is to look out for the rest, so we all look out for each other. But in the end, most thru-hikers have to be ready to be completely on their own for at least part of the trail.

During our research, we realized that every year, many experienced backpackers begin the trail with every expectation of success, only to fail. What makes the difference? Training? Motivation? Luck? Nope. It’s a simple matter of weather, and not even the weather during the hiking season. Rather, the biggest factor in completion rates is the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada. Since much of the Sierra’s snow falls in March, April, and even May, most thru-hikers have made the decision to hike in a particular year long before the size of the snowpack is known. Just the fact that we chose 2004, a pretty “normal” year for snowpack and for weather in general, was a stroke of good fortune for us. Subsequent years have been anything but.

Considering the time and expense involved in beginning a thru-hike, and the small chance of finishing, it’s not surprising so few people attempt to walk the entire PCT. The challenges are enormous, and the commitment is even bigger. All thru-hikers must train, buy gear, arrange to resupply along the trail, study guidebooks, and generally set aside their ordinary lives for five or six months. And for many thru-hikers (including us), there are additional headaches. We had to find reliable people to take care of our house, two cats, and a dozen or so indoor plants. I had to set up payment plans for the mortgage and other bills, and arrange time off from work. Mary had to finish all of her fifth grade class work 10 weeks ahead of schedule, which meant that as soon as she finished fourth grade, she began her fifth grade math, literature, and social studies at home. Luckily, the teachers and superintendent at Sunol Glen School were eager to help us in this regard, but what it meant for Mary was that she got no real summer vacation in 2003. Gary figured out what we would need in each resupply box, planned our town stops, and ordered all the gear. The financial hit can be substantial: By the time Gary replaced most of our old gear with the lightest, strongest, and warmest he could find, we were out thousands of dollars. That’s a big deal when your annual income is about to be cut in half.

By the time April 2004 rolled around, we were about as prepared as it was possible to be. We were probably the most prepared newcomers to the trail that year, mainly because we had to do so much extra to safely include a 10-year-old on an undertaking on the scale of a PCT thru-hike. Every possible safety issue had to be taken into consideration, and a child’s differing point of view had to be accommodated. We could never rely on luck. Thankfully, after all those years of hiking together, we knew what to expect. For example, a 10-year-old’s energy levels rise and fall differently than an adult’s, and rely more on her state of mind. At the beginning, Gary and I frequently took extra weight from Mary on steep uphill sections, especially in the desert heat. But Mary grew stronger as we headed north, while Gary and I developed a long list of ailments. By the time we reached Washington, Mary was carrying more weight, as a percentage of her body weight, than I was. But in April, of course, all we cared about was that the apparently endless preparations were finally over and all we had to do was put one foot in front of the other. Or so we hoped.

Once we started training, we discovered which bits of the avalanche of advice we’d received were the most important. One nugget that proved extremely important in guiding both my training and my actual experience on the trail was a chance quip by a longtime backpacker, Lipa, a retired park ranger and an experienced outdoorswoman. We ran into her on a training hike in Sunol Regional Wilderness, just a few miles from our home. She was planning to climb Mt. Whitney, California’s highest mountain and the highest point in the lower 48 states, for her 65th birthday. We told her about our plans. She listened approvingly, and then remarked: “Once you get to a certain level of physical fitness, the rest is all mental.” I took her words very much to heart and focused equally on physical fitness and mental preparation. I’ve met too many people who thought they could get by with just one or the other. Mary and Gary could train together frequently—Gary was a stay-at-home Dad, and Mary didn’t have all that much homework in fifth grade—but I worked full time and had to force myself to find opportunities for strenuous hikes with a heavy pack, or to work out on our one piece of home exercise equipment, a stepper.

Gary took charge of guiding the mental preparations for all three of us. I tend to rely too much on him to do the thinking, and also to provide the determination and motivation, for backpacking trips. Gary encouraged me to push myself beyond my comfort level, to hike in the rain (which I hate), to think ahead, to be more aware of my surroundings. During off-trail trips in the Sierra, he taught Mary and me to use the compass and topographical maps, watch for landmarks, figure out which drainages go where—in other words, to be prepared to save ourselves if he were hurt. Intellectually, I agreed that this was a terrific idea. But on the ground, breathing hard and going rapidly insane from mosquito assaults, it was all too easy to just turn the whole thing over to Gary. Gradually, however, I began to develop the right combination of determination, caution, and creativity. I learned when I could push myself to go farther—at the base of a 1,000-foot hill, for example, on a hot day, when what I really wanted to do was lie down on the fire road, put my cap over my face, and not move. I also learned when I should stop even before I really wanted to. This happened rarely, and usually only above 10,000 feet, where the thin air brought on a euphoric feeling that, like Julie Andrews, I could climb every mountain. Gary also pushed me to think in terms of solving typical backpacking problems, such as broken buckles or misleading instructions, by myself. (He didn’t entirely succeed. To this day, when something breaks or doesn’t make sense, Mary and I tend to turn to Gary first.)

The second bit of advice that helped me so much is a cliché I’ve heard so often that I had come to ignore it: Take one day at a time. It’s so common that a Google search brings up millions of hits. That is so trite, I had always thought. So banal. But it came to mean a great deal to me in the first few weeks on the PCT. As we struggled through the heat and rough terrain of our first 700 miles, I often asked myself, “Can I possibly keep doing this for another month? Another week?” The answer was often, “No way!” But if I asked myself, “Can I just make it to tonight’s campsite?” the answer was always yes.

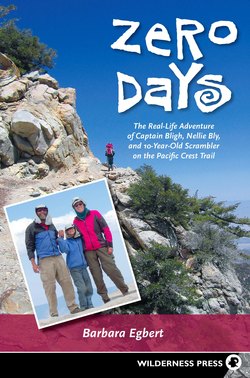

As our departure date neared, we had one more major chore to confront: choosing our trail names. The use of special nicknames is a long-trail tradition, generally considered to have begun on the Appalachian Trail. Some people choose their own, some have them assigned by other hikers, and some don’t use trail names at all.

Mary acquired her trail name, Scrambler, in the time-honored way of having it given to her by other hikers—her parents. This happened on our second thru-hike of the 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail in 2003, when we knew that we would be tackling the PCT the following year. We were heading down a very rocky section of trail near Aloha Lake, heading into Echo Lake. While Gary and I were making heavy weather of the bad tread, Mary was just skimming over the rocks, almost as though she were skating over the tops of them while her parents followed laboriously behind. “Look at her, just scrambling over the rocks,” Gary remarked enviously. And thus a trail name was born. We ran it past Mary, who liked it and promptly adopted it as her own.

Gary acquired his trail name from his daughter one evening a few weeks before we had to leave, while they were packing food, toilet paper, and other essentials into resupply boxes. He was, in her words, “bossing me around too much,” and she told him, “You’re just like Captain Bligh,” referring to the tyrannical captain in Mutiny on the Bounty. When I learned of the exchange, I endorsed the nickname because the real 18th century Captain Bligh was most famous as a navigator, and Gary’s wilderness navigational skills are superb.

I chose my own trail name, which is something many people do, sometimes as a pre-emptive strike against being stuck with something they don’t like. Nellie Bly, a name from American folk tradition, was the pen name used by the first American woman to be a true investigative journalist, back in the 19th century. She was an early hero of mine when I was growing up, and the children’s biography of her that I read probably had some influence on my decision to make journalism my career.

As a family, we became known on the trail as “the Blighs.”

Finally, we were ready to go—more than ready, in fact. Coping with the months of preparation, advance bill-paying, and arrangements to take off from work and school and to have the house and pets and cars taken care of left us with one burning desire: to start walking. So on April 8, 2004, a friend dropped us off at the border. We shouldered our packs, faced north, and began putting one foot in front of the other, on our way to Canada.