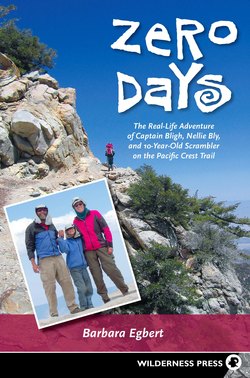

Читать книгу Zero Days - Barbara Egbert - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

TOGETHERNESS

Day 132: South Matthieu Lake. Today we spent the whole day cooped up in the rain. It was horrid to have so much togetherness.

—from Scrambler’s journal

IT FELT SO GOOD TO GET AWAY from the daily distractions and irritations of ordinary life. On the trail, we escaped from telephones, televisions, and computers; from bills, advertisements, and junk mail; from teachers and bosses; from paid work, housework, and homework. But we couldn’t escape from each other. We hiked together, ate together, slept together. Sometimes we even “went to the bathroom” together, our backs carefully turned toward each other to preserve an illusion of privacy, when there weren’t enough bushes to provide the real thing.

As much as we love each other, Gary, Mary, and I appreciate the ability to occasionally get away from each other at home. But on the trail 24/7, there was no escape. We saw each other all day. We listened to each other talk, eat, snore, and burp. We smelled each other as the days stretched out since our last showers. And sometimes, believe it or not, we got on each other’s nerves.

Adult hikers who travel as a pair or a group generally learn to respect each other’s hiking speed and style and often spread out along the trail during the day. One couple we knew left camp a couple hours apart to accommodate their differing abilities. They would wake up at the same time, but she would devour breakfast, dress, pack, and get walking as quickly as possible. He would get ready in more leisurely fashion, taking down the tent and doing most of the camp chores. Once he finally started walking, he usually caught up with his wife within a few hours. This approach worked well for them, although she had to make sure she marked her route carefully at trail intersections.

Some couples and even threesomes intend to stay together, only to discover early on how difficult it is for one person to match his hiking style to another’s. Standard advice: Don’t even try. If you want to hike with someone else, be content to share campsites and break stops, but don’t worry if you get separated in between. People hiking or doing any other task for hours at a time naturally settle into a speed that’s most efficient for them. Trying to adjust to someone else’s level isn’t just frustrating—it’s exhausting. Two people can start out the best of friends, but imagine how they’ll feel toward each other after a few weeks if their hiking styles don’t mesh.

Consider this scenario for two hikers—call them Eagle and Badger. Eagle gets up at the crack of dawn, packs up within half an hour, and puts in 3 or 4 miles on the trail before he stops to eat breakfast. Badger doesn’t wake up until the sun is high, cooks and eats a hot breakfast, then packs up at a leisurely pace. He might take 90 minutes to get out of camp—on a good day. Eagle moves fast but takes frequent breaks. With military precision, he sits down, eats a granola bar, drinks half a liter of water, and is on the move within 20 minutes. Badger walks for two or three hours between breaks, but then spends 45 minutes or so eating, filtering water, and treating his blisters. Eagle moves like lightning on the flats, slows on the upgrades, and crawls down the hills with aching knees. Badger moves at the exact same 2.5 miles per hour regardless of the terrain. Eagle stops only to take photographs, but then he might spend 15 minutes getting just the right frame. Badger doesn’t even carry a camera, but he’ll spend 30 minutes chatting with anyone he meets along the way. Force these two guys to stay together on the trail for more than a day, and watch out for the fireworks. But let them hike at their own pace, and when they meet in the evening to camp, they’ll get along great. Badger and Eagle will tell everyone later how lucky they were to find the perfect backpacking companion.

Gary, Mary, and I have different hiking styles, too, but we had fewer options than most hiking trios. Our rule was that Mary must be with an adult at all times. Frequently, we all three hiked together. I was a good pace-setter on moderate terrain, and often I would lead, with Mary (whom I generally addressed by her trail name of Scrambler) in the middle and Gary bringing up the rear. But if we split up, I was usually the adult who stayed with Mary. If Gary (a.k.a Captain Bligh) got ahead, he would wait occasionally for us to catch up, and he’d stop at any confusing trail intersections. But because of the size of his load, he couldn’t just stop and stand there; he had to find a suitable boulder on which to prop his heavy pack, which sometimes took a while. If the Captain fell behind, he usually caught up with us easily because of our frequent stops to take jackets off, put jackets on, adjust packs, or go behind a tree. Sometimes I became impatient with Scrambler, who initiated the majority of these pauses, but most of the time I was grateful that she and I moved at more or less the same speed. We chose 2004, when Mary was 10, to attempt our PCT thru-hike, partly because Scrambler’s speed and strength had increased to the point that she could keep up with Nellie Bly (that’s me) most of the time, and I hadn’t yet become too old and decrepit to keep up with her. Our joke was that we wanted to hike the PCT at just that magic point when Scrambler’s upward strength line crossed my downward one.

When she was younger, Mary needed a lot of cajoling to keep her moving. On the PCT, she just needed a lot of what Gary called “mindless chatter.” Mary loves to talk: It helps her keep going and takes her mind off the weight of the pack and the heat of the day. Gary does better without distractions. Listening to Mary and me talk endlessly about how we would design fancy costumes or plan a 15-course meal or redecorate our home if money were no object drove him insane. Sometimes we had to agree to let Gary stay a couple hundred yards in front or behind just so he’d be out of earshot. I’m somewhere in the middle on the talk vs. no-talk scale, but I did find that a half-hour quiet time each afternoon did me a world of good.

A typical conversation on a hot day on the trail went something like this:

Scrambler: Mommy, can we talk about the restaurant we’re going to open when we get home? Just pretend.

Nellie Bly: Sure, honey. Where shall we start?

Captain Bligh: Wow, did you see that hummingbird that just flew by?!

Scrambler: Yeah, Daddy, it was beautiful! Hey, Mommy, how about we call it the Hummingbird Restaurant and serve all-vegetarian food?

Nellie Bly: Sounds like a plan. Tell me more.

Scrambler: We’ll have pancakes and waffles and scones and muffins on the breakfast menu, and people could have them made to order while they wait, and you could bake them and I could be the waitress and Daddy could meet them at the door …

Captain Bligh: Wait a min—

Nellie Bly: Great idea, Scrambler. We could spend whole days dreaming up exotic kinds of food to serve, and if we stick with vegetarian, our ingredients won’t be all that expensive. And then we could offer lunch with all kinds of soups and breads and quiches. And we could hang hummingbird feeders outside all the windows for diners to watch.

Scrambler: Yeah, that’s a good idea! And we can have hummingbird-embroidered placemats and napkins and …

Captain Bligh: Hey, look at that lake down there! That’s the bluest blue I’ve ever seen!

Scrambler: Wow! Take a picture, Daddy! Hey, Mommy, we could have special desserts named after all our favorite places on the trail. Like Purple Lake blueberry pie. And Mt. Whitney chocolate cake.

Nellie Bly: Yes, and Golden Staircase ice cream sundaes. How about Mojave Desert broiled custard?

Scrambler: Yes, and Burney Falls blackberry shakes!

Captain Bligh: Don’t you two ever notice the scenery anymore? Here we are in one of the world’s most beautiful places, and all you can talk about is food!

Scrambler: We notice the scenery, Daaaad! We can talk and see at the same time! We’re giiiiirls.

Captain Bligh: Aaaaggghhh!

Before we left home for the trail, Gary’s friends at the rock-climbing gym he visits every week teased him that his real goal was to drive me to divorce him after six months on the trail, so he could spend even more time climbing. I thought that was pretty funny. We did drive each other crazy once in a while, but we’d learned on previous trips how to get along in the woods. That’s not the case with every thru-hiking duo or trio. We heard of one couple who had completed the trail a year earlier, put together a slideshow, presented it—and then got divorced. Romantic bonds less binding than matrimony have also become unraveled on long trails.

Trail journals provide a window into the relationships between people who find themselves hiking together, not always by choice. One online journal I read revealed a hiker’s resentment at being forced (in his opinion) to take responsibility for another who began walking with him in the southern desert. At first he enjoyed her company, but eventually he came to fantasize about ditching her. Another journal contained a backpacker’s bitter words about getting into a town stop with another hiker, who pulled a vanishing act at the first opportunity. More common, however, are reports of deep friendships formed along the trail.

The social aspect of thru-hiking is very important to some hikers—so important, in fact, that when we chatted with a bunch of Appalachian Trail thru-hikers in 2005 in Maryland, they mentioned one solitude-averse hiker who had quit the PCT because he met only a dozen people in a week on the trail. He returned East to hike the AT again, where it’s common to see a dozen people in just one day. Millions of people walk on the Appalachian Trail every year, most for dayhikes or weekend outings. But somewhere between 2,000 and 3,000 attempt thru-hikes each year, 10 times the number who start the PCT. And thousands more are doing section hikes on the AT. Most backpackers plan their days around the 250 shelters along the trail, so the AT during the day can be almost as well-used as a city sidewalk, and the shelters at night can be as crowded as a Yellowstone campground on Labor Day. This scene isn’t for me. I loved going for days on the PCT without meeting any strangers, and I would go crazy if I had to share an AT shelter every night with eight or 10 other people.

Partnerships formed on the trail can become a wonderful source of companionship, but they can also become the cause of deep irritation. Gary insisted before we start that we all agree on one thing: We wouldn’t let anyone glom onto us. If someone occasionally opted to hike or camp with us, he said, that would be fine, but under no circumstances should we let anyone join our group to the extent that we would be expected to alter our schedule for him or her, or in any way take responsibility for another person. I thought at the time Gary was overly insistent on this point: What would be the harm? And how long could someone possibly stick around?

I realized how smart he was to insist on this policy later when we ran into one backpacker near Lake Tahoe who gave us cause for concern. He seemed friendly at first, but soon we noticed he was subtly trying to boss us around and take charge of our decisions. When we arrived at a popular backcountry campground that evening, he tried to tell us where we should set up our tent and hang our food. We chose our own site and stashed our food in our usual way. (Later, a bear tried to get his food, but ignored ours.) The following day, we drew ahead of him when we chose to tackle a 1,000-foot elevation gain at the end of the day, and he chose not to. We didn’t see him again. We did hear about another backpacker, however, who didn’t find it so easy to ditch this guy. The desperate hiker finally got up very early one morning, snuck out of camp, and walked 30 miles to escape the pest.

We were not strong hikers by PCT standards—we never reached the 30-mile-a-day pace many backpackers achieve—so we wouldn’t have been able to outrace a strong hiker really determined to keep up with us. And time-wise, we couldn’t afford to take unscheduled zero days to let an unwanted companion get well ahead of us. Luckily, the few people we met whom we disliked either fell behind or dropped out, sparing us any unpleasant confrontations.

For the most part, it was just each other we had to deal with, on and off the trail, which was good sometimes and not so good at other times. Niceness and politeness in particular took a severe beating during the last few weeks we spent preparing for the trail. It wasn’t easy for friends and relatives to be around us during this period, especially one friend who stayed with us the last few days and then drove us all the way to the border. Gary and I were up past midnight every night counting supplies, putting precise numbers of vitamin pills in Ziploc bags, estimating toilet paper use, and so on. Then we’d get up after only a few hours of sleep to get Mary off to school. What with the stress and lack of rest, we became the classic Mr. and Mrs. Bicker, snapping at each other and generally leaving behind all pretense of a respectful relationship. The stress didn’t end when we thought we were ready to leave the house. Our friend, Mary, and I were in our cars and actually had our seat belts fastened when Gary decided we couldn’t leave. He didn’t feel confident that every last little item had been adequately and redundantly and obsessively counted and packed and checked. We got out of the cars and I called my sister, Carol, in Carson City to let her know our arrival would be delayed by one day (we were going to leave one car at her house). I ordered Chinese takeout, and then we spent another night in Sunol. The next day we finally did get going.

Thru-hikers sometimes have to be brutally honest with each other. As the leader of our little group, Ol’ Cap’n Bligh had, on occasion, to lay out some unpleasant truths. Gary had been involved in two expeditions to Denali in Alaska—one successful, one not—and he knew from those and other experiences that an expedition is doomed if it has the kind of group dynamics that value niceness and politeness at the expense of honesty and attention to detail. He frequently challenged us, and his remarks sometimes seemed hypercritical. But hurt feelings are a small price to pay for safety.

Nine years earlier, when he was preparing for his first expedition up 20,320-foot Denali, Gary was anxious, short-tempered, and frequently frustrated with everything that had to be done. This climb was fulfilling a dream Gary had pursued for many years, and I naively assumed that the last few months would be a time of happy anticipation, rather like a child’s run-up to Christmas. Silly me. About two months before he was due to fly to Anchorage, I came down with a cough bad enough to send me to the doctor. He diagnosed bronchitis, and put me on antibiotics. Then Mary, just 16 months old, acquired a deep, racking cough unlike anything she’d ever suffered. This time, the pediatrician took a nasal swab, and the next day she gave us the shocking diagnosis: whooping cough. We’d all been immunized and, furthermore, we thought whooping cough had gone the way of smallpox and polio, no more to be found in the developed world. We were wrong. The next thing I knew, Mary and I were spending the night in an isolation ward at the Kaiser Permanente hospital in Walnut Creek. There, she had a little gizmo shining a light through her finger so her blood oxygen could be measured, and every few hours she coughed so badly that she would throw up. Gary got sick, too, and he and Mary were quarantined for a week at home while the antibiotics took effect. And in the middle of all this, our beloved elderly cat died. With Gary’s training schedule in disarray and his health in question, he seemed to me both insensitive and selfish. I really hadn’t grasped that with a major mountaineering effort in his near future, he had to look out for himself more than for us. He had to be picky and self-centered if he wanted to survive. But I didn’t know that. By the time I took him to the airport, I was ready to tear up the return half of his ticket.

So in 2004, it came as no surprise to me that we were at our worst during those frantic last days. But we were hardly unique in that regard. Many thru-hikers also start the trail in something less than an ideal frame of mind. There are others whose leave-takings with spouses are tense, whose parents are reluctant to let them go, who wonder if relationships will survive or erode during the next six months. Those people are out there, but they don’t talk about it on the trail. Once people start hiking, they generally shake off all those doubts and stresses, at least for the first few weeks. All that really matters is that they’re finally walking. Everything lies ahead, and only Mexico lies behind.

WITH THE STRESS OF PREPARATIONS finally over, we began our hike as a family. And, of course, as a family, the dynamics of how we behaved at home continued on the trail. A complete change of surroundings didn’t change the fact that Mary and Gary share many personality characteristics, including stubbornness. This made for more than one tense day in the backcountry. As for getting out of camp in the morning—well! Any parent who has ever shouted at a dilatory child to “for heaven’s sake, find your shoes and put them on before the school bus gets here” can understand perfectly well what it was like for us. (How Mary could misplace so many personal items in the confines of a 6-by-8-foot tent is a mystery to this day.) We accomplished many goals during our six months of hiking together, but achieving quick starts in the morning wasn’t one of them.

Nonetheless, backpacking as a trio was wonderful. We were never lonely, on the trail or off. The longed-for but sometimes disturbing phone calls home that thru-hikers make during town stops, with their reminders that loved ones are far away and relationships and responsibilities are being neglected, didn’t trouble us. Our most important relationships were moving up the trail right along with us. The PCT became a shared experience we can draw on for context the rest of our lives. A day featuring particularly heavy rainfall will always be “an Olallie day,” and an unexpected treat will be “like that Gatorade near Bear Valley.” If I want to warn Mary that a new acquaintance strikes me as untrustworthy, I need only say, “He reminds me of Zeke.”

Having Mary along set us apart from the multitude of what some people refer to as “hiker trash.” Her presence guaranteed us a warm welcome and often an admiring audience at many of our stops. As a pre-teen attempting to walk from Mexico to Canada in one year, Mary inspired scores of parents to reconsider their own children’s outdoor experiences and ambitions. As trail celebrities, in a minor way, we occasionally enjoyed greetings such as, “Are you the famous 10-year-old?” (from a teacher hiking near Kennedy Meadows in the southern Sierra) and, “So you’re the famous family!” (from the postmistress at Belden in northern California). When everything from our feet to our feelings was hurting, the open admiration we encountered gave us a tremendous boost.

When we returned home, adjusting to routine life was made infinitely easier because of the shared nature of the experience. Solo thru-hikers in particular often find it terribly difficult to make that transition, because there is no one who can hold up the other end of the conversation. True, everyone asks questions, but they’re invariably the same questions. Once the returning hiker has explained how boxes of supplies are mailed to post offices and how food is protected from bears, conversations usually revert to the latest news about jobs and politics and vacation trips to Disneyland. As Triple Crowner Jackie McDonnell put it in Yogi’s PCT Handbook, her guide to all things PCT, “They’ll never understand.”

In our self-assumed role as crusaders for childhood exercise, Gary and I spent a fair amount of time talking to people we met along the PCT and explaining how it was that two 50-somethings and a 10-year-old could tackle a 2,650-mile trail. We told them all about our family values of exercise, good nutrition, and healthy living.

But as we worked our way up the trail, many of our other family values fell by the wayside or had to be adapted for the trail. I spent a lot of time thinking about these as we progressed on the trail:

EQUALITY: At home, I am the breadwinner, while Gary is a stay-at-home father. We spend most holidays with my family, but we fly East every year to visit his friends and relatives. I do the cooking, Gary does the laundry. I pay the bills, he keeps the cars running. We both wash the dishes. Sounds like the very model of a modern-day marriage based on equality between the sexes, but put us on the trail and it all disappears. I told Gary before we even started, “There are going to be times when I am too cold, wet, hungry, and miserable to even think. At those times, you will have to take charge, tell me what to do, and tell me in words of one syllable. Don’t worry about hurting my feelings.” Several times, I stood alongside the trail, cold, wet, and hungry, and moaned to Gary, “What shall I do?” Groan, whine, whimper. And Gary, who was also cold, wet, and hungry, would tell me what to do.

Now, I’m not totally insensitive. There were plenty of times when I resented Gary’s commands. I’d think to myself, just you wait until we get home! I’m going to tell you just where to put the dishes and just how to wash the clothes and just how to vacuum the living room rug! And I’ll use that same snarky, sarcastic tone of yours, you jerk. There were times when I thoroughly understood the homicidal feelings some people hold toward the leader of an expedition. Several years ago, I read the book Shadows on the Wasteland, by an Englishman who skied across the Antarctic with another explorer. The author, Mike Stroud, described his feelings on an earlier expedition—an effort to reach the North Pole unsupported by dogs, machines, or air drops—toward his partner, Ranulph Fiennes. Each pulled a heavy sled, and they had a gun to use against polar bears. It was clear from the start that Fiennes was the stronger of the two, and he was usually way ahead. This bothered Stroud. A lot. In fact, it bothered him so much that one day he concocted an elaborate plot by which he would catch up with his partner, pull out the rifle, and kapow! Death to the evil one. He would throw the body into the ocean, and make up a story about a polar bear and a frozen gun. He could call off the trip and still go home a hero. I never got quite to that point of resentment on the many days when I had trouble keeping up with Gary, either because I had to stay back with Mary or because I just couldn’t move that fast. On the other hand, I didn’t carry a weapon, either.

There were times when Gary reminded me of the tyrannical Captain Bligh in the movie version of Mutiny on the Bounty. But Gary didn’t want to be a trail dictator. Rather, he put considerable effort into teaching us how to be more independent.

It was a hard job. Take our packs. I thought because I had been carrying a backpack on our vacation trips for more than 10 years that I knew how to assemble one. Nope. I didn’t know squat. Gary had shown me how to pack, but somehow I hadn’t absorbed the reasoning behind the lesson. Finally, he had to line up Mary and me and give us a demonstration: light, bulky things like sleeping bags and down jackets in the bottom. Then the heavier things higher up, and close to the body. He repeatedly emphasized that point: Everything heavy should be packed so that it’s in the top half of the pack, and as close to the hiker’s body as possible. Water bottles should be arranged so they won’t slosh—and on hot days, they should be insulated with clothing to retain their morning coolness. Gary is a slow, meticulous packer, much to the irritation of more slapdash packers—me, for example. But once Gary gets moving, he doesn’t have to stop to adjust the contents of his pack. I started each day determined to emulate him, but it never seemed to work out. When Gary distributed items of mutual use among us, I ended up carrying each day’s food bag and the trowel bag, which contained the trowel, toilet paper, baby wipes, and Ziploc bags for used toilet paper. (We carried out all of our toilet paper so that it wouldn’t be dug up by animals or uncovered by wind and water. Too many popular backpacking routes nowadays are lined with used toilet paper, and we didn’t want to contribute to the unsightly result.) Every time we stopped, I had to pull out at least the food bag, probably the trowel bag, and frequently smaller items such as the foot-treatment kit, sunscreen, and insect repellent. I never could seem to get everything back in quite the same order as when I’d started. As a result, my pack would gradually become unbalanced and tilt to one side, adding to any other resentments I had picked up during the day.

A few weeks later, Gary gave us another lecture, this time about toilet paper. We had been on the trail more than a week since Kennedy Meadows and still had several days to go before reaching Vermilion Valley Resort, our next resupply point. I was suffering from a bit of diarrhea, so I was using more toilet paper than planned. Gary was shocked to discover we were getting low on the precious stuff, and even more shocked to learn that Mary and I fell into the category of people who wad up their t.p. before using it (a wasteful habit, in Gary’s opinion), rather than tidily and frugally folding it. Fifteen years of marriage, and he’d just now figured this out. This time, Gary lined us up and proceeded to give a drill sergeant’s rendition of Personal Hygiene 101. “You don’t have to use more than eight sheets of paper per day!” he exclaimed. “You don’t wad it up! You fold it in half, and use it, and then fold it in half again. And then you use it again, and fold it up and use it one more time!” All of this was accompanied by appropriate hand gestures and body posture to indicate how to accomplish the goal. Gary was dead serious about this. Running out of toilet paper is no laughing matter. But Mary and I couldn’t help ourselves. We kept seeing him through the eyes of a possible stranger traipsing down the trail and coming across our little tableau. We just couldn’t keep from giggling. However, we did take the lesson to heart, and rationed our cherished toilet paper carefully until we got to Vermilion Valley.

Stream crossings brought out the worst in me. Gary has good balance and can cross rushing streams on slippery rocks or teetering logs. Mary can, too. I take one look at anything less sturdy than an Army Corps of Engineers bridge and freak out.

Usually, our stream crossings went like this:

Captain Bligh: Well, don’t just stand there, look for a good way across.

Nellie Bly: Hmm …

Scrambler: I’ll just wade across.

Captain Bligh: No, you won’t. You’ll hurt your feet on those sharp rocks. And it takes forever to get your boots and socks back on. Here, look, this log goes halfway across, and then you just step on that boulder, jump over there, and you’re done.

Scrambler: Hmph.

Nellie Bly: Looks impossible to me.

Captain Bligh: Just watch. … See? All done.

Nellie Bly: Hmph.

Scrambler: Hey, look at me!

Captain Bligh and Nellie Bly: Be careful!

Captain Bligh: Very good, Scrambler. Now you, Nellie.

Nellie Bly: I’m sure there’s a better place downstream …

Captain Bligh: No, there’s not. Now just come across or we’ll be here all day!

Nellie Bly: I’ll try … Oh! … Ouch! … Oof! … Aaaaggghhh!

Stream: Splashhhh!

THRIFT: Frugality was another family value that disappeared. It vanished long before we even got on the trail. On the “You might be a thru-hiker …” list posted at one trail angel’s home in southern California, an item reads, “If your REI dividend last year was over $150.” REI, or Recreational Equipment, Inc., is the giant co-op based in Washington state. (I think of the Seattle store as the REI mother ship.) It returns to each member a dividend of about 10 percent of what that person spent the previous year. For a family of three determined to replace every last piece of heavy, outdated gear with the lightest and most modern stuff possible, $150 is chicken feed. Our dividend from REI for 2003 was $318.18, and REI was only one of the many places we shopped. When it arrived in the mail, I just stared at it. I couldn’t imagine how we could have spent more than $3,000 at REI alone.

Gary and I dislike spending money. He buys his jeans from Goodwill, just like fashion-conscious high school students, although not for the same reason. I’m still wearing outfits to work that date from the Carter administration. (The trick is to change jobs every time the White House switches parties. That way, co-workers don’t notice how your wardrobe never changes, year after year.) But when it came to equipping ourselves for the PCT, money was no object. I had to stifle my objections every few days when I’d come home from work and Gary would tell me he had tracked down just the right jacket, or the world’s lightest ice ax, or that he had finally found a tent that would hold the three of us but still weigh less than 6 pounds. The credit card bills began mounting. And that was nothing compared to our on-the-trail expenditures. I’m famous for tracking down inexpensive motels—I once wrote a newspaper article about the techniques involved in finding cheap but comfortable lodging—and I’ve been trained since childhood to scrutinize the prices on a restaurant menu a whole lot more carefully than the menu items themselves. But those habits of a lifetime soon disappeared.

We started out well. Our town stop plans called for lodging at Motel 6-type establishments and eating at diners or fast-food places. But, oh, how that changed as we worked our way north. As most of the other thru-hikers fell by the wayside, so did our sales resistance. In Mojave, in southern California, we paid about $60 for a night at White’s Motel, and ate at McDonald’s. At Echo Lake, we bought sandwiches and fruit smoothies at the lodge, but eschewed the temptations of a motel night in South Lake Tahoe, camping at Aloha Lake, instead. At Belden, we cheerfully paid $85 for a cabin, ate any hot food the bar had to offer, and scoured the little store for extras. And by the time we’d suffered the rains of Oregon, we were ready for the Timberline Lodge on the slopes of Mt. Hood. I’m glad we slept and ate at Timberline, because we’ll probably never do it again. We could never afford it. Pay $125 for one small room? Fork over $25 for a plate of fish and veggies? Granted, fish at the Timberline isn’t anything like the stuff Long John Silver’s calls fish. Oh, no. Fish at the Timberline is baked Alaskan halibut in chipotle apricot glaze, with lobster risotto, pickled onions, and organic asparagus on the side. Or it might be Pacific ahi, crusted with toasted coriander and ginger, paired with a crispy macadamia nut sushi roll, Chinese snow cabbage slaw, and sweet orange soy reduction over more of that organic asparagus. And it’s not served by a pimply teenager stabbing a finger at the food symbols on a cash register, but by a waitress who’s pursuing a Ph.D. at Oregon State University in her spare time. On the other hand, we probably came out ahead by the time we finished breakfast the next morning. For $12.50 apiece, we got the all-you-can-eat breakfast buffet, and by the time we finished, all we could do was lie on our comfortable beds and groan. While we were eating, other lodgers came in, ate, and left, then more came in, ate, and left, then more. In all, we gobbled our way through the equivalent of three shifts of diners, and even got free beignets.

MANNERS: I tried. I really tried to develop a salty vocabulary on the trail. But my good Lutheran upbringing wouldn’t let me do it. I managed an occasional “hell” if I not only slipped on a boulder but banged both shins while crossing an ice-cold Sierra stream. And I managed to squeeze out a few “damns” here and there when the mosquitoes per square inch of skin exceeded a dozen, or when I stubbed a blistered toe for the tenth time in one day, or when I realized that the road crossing we’d just reached still left us 10 miles short of the campsite I had confidently anticipated seeing in just half an hour. But I never became any good at it. Gary, on the other hand, swore like the proverbial sailor, and used up the entire family’s quota of cuss words in an average morning. Mary, being 10, was the manners police officer for all of us. Ask the parents of most any grade-school child, and they’ll tell you how that works. Little Miss Enforcer never missed a chance to remind us that good manners could and should continue on the trail. And Gary never missed a chance to push her buttons.

Somehow, I always found myself in the middle of these discussions, which usually went something like this:

Captain Bligh: Burrrrppppp!

Scrambler (after waiting for a good three seconds): Daddy, say, “Excuse me.”

Captain Bligh: Daddy say excuse me.

Scrambler: Daddy! Say, “Excuse me”!

Captain Bligh: Say excuse me!

Scrambler (louder and more agitated): Daddy! Excuse yourself!

Captain Bligh: Excu—

Nellie Bly: Oh, shut up, both of you!

Captain Bligh and Scrambler (in unison): We don’t use that language in this family!

Nellie Bly: Well, excuuuuuuse me!

CLEANLINESS: Hah! Normally the kind of people who obsess over showers and clean clothes, we were the trail’s dirtiest hikers. Others somehow found time to take dips in lakes and streams, but slowpokes that we were, we always seemed to have barely enough daylight to get from tent site to tent site, eat, and sleep. It got to the point that Mary found clean people objectionable because the fragrance of their soap, shampoo, and deodorant was too strong. We have photos of our legs as black as obsidian from shorts-level to socks-line. We did wash our hands after every “bathroom break,” which is more than many backpackers can say. But without soap, our hands always looked grimy. And our fingernails were just filthy.

I hadn’t always felt so comfortable with dirt. When Gary and I first started backpacking, I insisted on taking along enough clean socks and underwear to put on fresh pairs every day, and enough T-shirts to change every other day. I would bathe in cold streams if nothing better was available. Gradually, I learned that I didn’t need clean clothes to survive, and that just because I smelled as bad as a three-day-old corpse, I wouldn’t automatically become one. On the PCT, we each carried two sets of clothing—shirt, underwear, and pants—and wore one set between each pair of town stops, saving the clean set to put on after our showers while the dirty clothes were being laundered. The one thing we carried an ample supply of was socks. We realized early on that dirty, gritty socks contributed to foot problems, and on many days in northern California, I spent my snack breaks washing socks in the dwindling creeks, downstream from where Gary was filtering water. We would dry the wet socks by hanging them over the horizontal straps on the outsides of our packs, cinched tight so nothing would fall off. In case there was any doubt, this clearly identified us as thru-hikers. After Captain Bligh spilled a bit of macaroni and cheese on his trousers during dinner, Mary wrote a brief journal entry that summed up the state of our personal hygiene: “Dad spilled food on himself. He thinks he’ll smell like sour milk. What’s the difference?”

Our hygiene was a little better when it came to food, although we occasionally ate something that had touched the ground briefly, as long as it didn’t look dirty, and there were no cows around. I forget who told us the M&M riddle, but it came to express my views pretty accurately:

Question: How can you tell different kinds of hikers apart?

Answer: Put a red M&M on the ground. A dayhiker will step on it. A section hiker will step over it. A thru-hiker will pick it up and eat it.

PRIVACY: In a tiny tent? Gimme a break. We did have our customs that provided a little privacy. I would wake up first, get into my clothes, and then wake the others. Mary, being so small, figured out how to dress inside her sleeping bag. Once we were both out, Gary would dress. But there were plenty of times when we all had to change clothes at once, and just ignore each other. Bathroom breaks were no problem during the first several weeks—we were among the first on the trail, and during April and May, we often went for days without seeing a soul. When nature called, I would just step a few feet off the trail and squat while Gary and Mary traveled on. (When it was Mary’s turn, I stayed with her.) But on the more popular sections, I got caught a couple times. Luckily, the two men near the San Joaquin River in southern California pretended they hadn’t seen me. The seven or so hikers near Thielsen Creek made believe that being mooned on the trail was just another part of the Oregon outdoor experience.

FOLLOWING THE RULES: For backpackers, Gary and I are on the obsessive side of the ledger when it comes to obeying regulations. We get permits to hike, we get permits to camp, we fill out all the forms, we follow the rules about fires, and we stuff our dollar bills in those little “iron rangers” if no live rangers are there to collect our money. We’re that way in private life, too. We pay our bills on time, drive the speed limit (OK, I go 5 miles per hour over), and never miss a vehicle registration deadline. We started out on the PCT with every intention of continuing our straight-arrow ways. Gary wrote in for our trail permits and paid for the Whitney stamps so we could climb the highest peak in the lower 48 states without worrying about hassles at the top. (Only a few thru-hikers skip the permit stage, but many don’t bother getting the Whitney stamp.) We generally camped where we were supposed to, never built a fire, disturbed no archaeological treasures, and harassed no endangered species.

But as we moved north, we discovered that you can’t do the trail and still follow all the rules. In serious bear country, we were really careful about food storage, but there were rainy nights in Oregon when we slept with our food in the tent. As for campsites—there were places where we just couldn’t obey every last regulation. I particularly remember a long section of trail approaching Castle Crags State Park in northern California. The guidebook noted that camping was illegal for several miles before the park border, because the trail ran through private property. And it was also illegal to put up a tent once inside the state park, where camping was allowed only in established campgrounds, and the trail didn’t go through them. Thanks to water concerns and other logistics, there wasn’t a way we could avoid camping somewhere in that stretch. Imagine my complete lack of surprise when, just before the park border, we found a spot where people obviously camped quite often, sometimes in large numbers. We stayed there, too. We bent the rules as little as possible, but without some bending, it would have been very difficult to finish.

We also went from purists to pragmatists when it came to staying on the official Pacific Crest Trail. We all agreed on our definition of a thru-hike: Walk all the way from Mexico to Canada in one calendar year, with all sections linked together on foot. (For example, if we had to skip a section due to a forest fire, which often happens to PCT thru-hikers, we would have to go back and walk it after finishing the rest of the trail.) We also started out determined to stick with the trail as much as possible. During our town stop in Idyllwild, we engaged in a long discussion of whether we did wrong to take an alternate route, the Little Tahquitz Valley Trail, when we couldn’t stay on the official route because it was buried under snow and I kept falling down. My feeling was that the detour was perfectly OK. Bolstering my opinion was the fact that another hiker, Walks Alone, had to drop out because he broke his collarbone falling on the slippery official route. That could have easily happened to me. As we moved north, we kept it official as much as possible, but when the weather began to worsen, we took occasional alternate routes, especially if they were recommended in the guidebook. Taking an alternate route sometimes was safer, but not always. The closest we came to risking death was in September when we decided to walk around Russell and Milk creeks because of their reputation for danger during rainy weather, which—this being Oregon—we had seen a lot of. From Pamelia Lake, we hiked down to a highway, and the next day had to walk through a construction area that put us right smack in the path of high-speed traffic. I still shiver, thinking about those huge vehicles hurtling down on Mary as we rushed along the road.

PUNCTUALITY: When Mary was born, the reputation for punctuality that Gary and I had built up took a severe hit. As new parents, we had an excuse. But on the PCT, there was no excuse for our inability to get out of camp more quickly each morning. Three hours to break camp and get walking, without even cooking a hot breakfast? Good grief. The most humiliating day was the time we camped with a thru-hiker with the trail name of Pineneedle at Spanish Needle Creek two days before Kennedy Meadows, which marks the end of the southern California section of the trail. We had a 25-mile day ahead of us with significant altitude gain and loss, so we got up at 4:30 a.m. We did cook breakfast that morning, probably because we had more freeze-dried food left than any other kind. We really pushed hard and managed to get out of camp at 7:10. Meanwhile, Pineneedle woke up at 6:30 a.m. and left at 7. He just got up, packed up his tent and so on, put on his boots, and hit the trail. Amazing. We weren’t any better at sticking to our original schedule, which called for us to finish the PCT in early October. We lost a day or two in the first seven weeks through the desert, then lost another four days because it took us so long to complete our resupply work while we were at home after our June trip to Maryland. We took unplanned zero days at Vermilion Valley, Carson City, and again at Cascade Locks, Oregon, when I realized I would have to leave the trail temporarily for dental and medical treatment. We had to spend a day at the Portland REI buying a two-person tent for Gary and Mary to continue with, plus some cold-weather gear. We lost so many days that when we finally headed into a late-October snowstorm in hopes of completing the final stretch of Washington state, we were the last people on the trail.

SIMPLICITY: We’re not Luddites, honest. We decided, years ago, for perfectly logical reasons, against having a television set at home (and thus no VCR, no video games, and no video cameras). Same goes for cordless phones and cell phones. So it was ironic that when we headed out on the trail to spend time outside of civilization, we were lugging a video camera, a cell phone, and a new digital camera that we didn’t even figure out how to use properly until halfway through California. The digital camera replaced the film cameras we had used and abused over the years to the point of unreliability. The video camera was for shooting film for a documentary that died stillborn but that seemed like a good idea at the time. And the cell phone was for calling motels and arranging rides along the way. Many backpackers whose houses are loaded with the latest technological wizardry deliberately eschew all gadgets on the trail. Some don’t even carry a camera or a wristwatch. We felt as though we were the last people in the English-speaking world to acquire a cell phone, but once we had it, we were glad we had brought it along. It’s no good for emergencies—there’s hardly any cell phone coverage in the backcountry—but it was very useful for calling for a ride from the trailhead and for calling friends and relatives when motels lacked working telephones.

We didn’t carry a TV with us, of course, but we watched more television while we were thru-hikers than we ordinarily see in an entire year. At almost every town stop, we’d check into a motel. And before long, Gary and Mary would be glued to the screen. Channel surfing drives me into a homicidal rage, so I generally retreated to a corner of the room with the newspaper and tried to ignore the monster truck pulls, cooking programs, historical re-enactments, and ancient cartoons they were watching. I couldn’t help noticing that at one town stop in Oregon, Mary watched The Matrix, which struck me as not entirely suitable for a 10-year-old. But I decided to let Gary be the adult that night, as far as monitoring the TV went.

Living without television at home is a major plus for anyone who wants to have a family that’s seriously involved in outdoor adventure. That wasn’t why we got rid of ours before Mary was born (we did that because we feel television is the biggest time-waster ever invented), but it turned out to be a big help. Without spoon-fed electronic entertainment, children grow up learning how to create their own entertainment, indoors and out. They learn to be content with a lightweight paperback book for relaxation, and to focus on the real world long enough to watch a hummingbird visit a feeder or a deer climb a hill. In the wilderness, Mary likes to braid pine needles while walking, and in camp she depends on her imagination to create stories around the towns she builds with rocks, twigs, and pinecones. Kids who grow up with TV are attuned to fast-moving, all-engrossing entertainment, and it’s hard for them to make the transition to the slow-moving natural world. But for Mary, no TV and no VCR meant she grew up without knowing quite all the characters on the Cartoon Network, without memorizing all the lyrics to The Little Mermaid, and without playing video games. And thus, she didn’t miss them on the trail.

ENVIRONMENTALISM: I should have felt really good about this one. We followed Leave No Trace standards as much as possible, including packing out our toilet paper, which is more than most hikers do. And, of course, we weren’t burning any gasoline on the trail. But although we didn’t drive a car for most of the time, I made up for it during the last month, driving about 5,000 miles to get home, get back up to Washington, play trail angel all over the state—including side trips to Yakima and Seattle—and then finally go home again. In the end, I probably drove as many miles as if I’d never set foot on the PCT that year.

IN SPITE OF THE CHANGES we made to our family values on the trail, the one we did retain, without compromise, was togetherness. It may have been horrid, as Mary suggested in her journal entry at the beginning of this chapter. Sometimes we were so much on the outs with each other, I thought we’d never be on speaking terms again. But we’ve always been a close family, and it was that willingness to stay close, no matter how badly we wanted to divorce and disown each other, that formed us into a group capable of taking on almost any challenge. The hardest thing for all of us was when we split up in September, when I had to return home briefly for medical treatment, and Gary and Mary had to continue without me. And the happiest day for me was when we teamed up again in Mazama, Washington, to take on the frozen barrier of the North Cascades. We were worried, we were stressed, we were in some degree of danger. But we were together again.