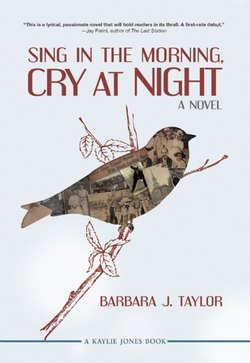

Читать книгу Sing in the Morning, Cry at Night - Barbara J. Taylor - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

BY THE TIME THEY GOT TO LEGGETT’S CREEK, one of the better fishing spots in the Providence neighborhood of Scranton, and cast their lines, Violet had discovered that Stanley was anything but stupid. He could do numbers in his head, even his times tables up to eight. He could name at least forty of the forty-eight states, including Arizona and New Mexico, which had only been added the year before in 1912. And he could call birds better than the birds themselves.

“Shush,” Stanley said. “Hear that?”

“Hear what?”

“That blue jay,” Stanley whispered as he pointed across the creek toward a thick line of hemlocks.

“I can’t see anything.” Violet stood up and stretched on her toes to see what Stanley saw.

“Listen.”

Violet sat down, closed her eyes, and focused on the bird’s triple-noted whistle, a high-pitched twee-dle-dee, twee-dle-dee, like the old nursery rhyme. The song repeated several times, and then a nearby blue jay, too near for Violet’s comfort, returned the call. Violet leaped up with arms flailing in an attempt to shoo the bird. She’d heard from her neighbor Tommy Davies that blue jays would peck a soul to death. No need to take chances.

Stanley sat at the edge of the creek, doubled over in laughter. “That was me, you silly goose.” He blew into his cupped hands, and the bird sang again. He straightened right up when he saw Violet’s red face. “Aw, come on. I’ll teach you if you like.”

Violet stood, arms folded, mouth turned down, until Stanley had apologized half a dozen times. She thought six an adequate number of “I’m sorrys,” especially since she really did want to learn how to call birds.

“We’ll start with the sparrow. He’s an easy one. Think of your mother when you’ve let her down.”

Violet’s eyes flashed with tears.

“Or a teacher when you’ve made her real mad,” he added quickly. “That’s a better one.” He raced on: “You know, when she makes that tsk, tsk sound with her tongue on the roof of her mouth.” He fired off a series of eight or twelve trilled tsks, too quick to be counted.

Much to Violet’s surprise, a sparrow immediately returned the song. “How’d you learn to call so good?”

“Mama. She had what Pa calls a gift.”

Had. Violet paused to digest so small a word.

“Rheumatic fever,” Stanley added, in answer to her unasked question. “It’ll be a year next month.”

So that explained it, Violet thought. No mother to make him go to school. She glanced at Stanley’s dirty face and clothes. No mother to make him wash behind his ears or change his britches. She pulled in her line, rethreaded the half-dead worm on the hook, and cast back into the water.

“You’re not doing it right,” Stanley said, flinging his line out twice as far as hers. “It’s in the wrist.”

“Who made you boss?”

“I’m older,” he said. “Been fishing longer.” The tip of his pole bent toward the creek. “See?” He smiled broadly as a mud-colored sucker with a hook in its cheek broke the surface of the water. “Biggest one yet.”

“Sing in the morning,” Violet warned, “cry at night.”

“How’s that?” Stanley asked, just as the line snapped. They both watched wide-eyed as the sucker disappeared downstream.

“Don’t count your fishes until they’re caught.” She stifled a giggle before handing him her pole to share.

* * *

“You’re going to catch hell when you get home,” Stanley said as they admired two suckers and a chub strung by the mouth and gills on a piece of rope.

Violet knew truth when she heard it, and marveled at Stanley’s ability to express it so effectively. Not only had she skipped a whole afternoon of school, but she’d skipped a whole afternoon on the first day of third grade.

On their way home, they tried to think of an excuse, not that Stanley had any particular need for one, but he wanted to help Violet, especially since fishing was his idea in the first place.

“You best take them all home,” Violet said, eyeing the chub she’d caught not an hour before. “If I walk in the house with a fish,” she paused to consider her words, “I’ll catch hell.”

* * *

Grace plodded into the kitchen, clamped the meat grinder onto one end of the table, and started in on a supper of ffagod, Owen’s favorite Welsh dish. She minced the pig’s liver and onions before folding them into a bowl of suet and breadcrumbs, seasoned with a light hand. It had been weeks since Grace felt well enough to tend to a meal, and she hoped Owen would notice her effort. After flouring her hands, she started rolling the mixture into egg-sized portions. Not having added any coal to the stove since morning, Grace looked over at the bucket alongside it. Three-quarters full, more than enough to keep the oven going.

She pulled her eyes straight back, ignoring the lightly bruised wall where a few of the blueberries had landed that day. Ignoring the purple pinpricks that would inevitably bleed through this latest coat of paint. Not today. Not now.

Not again.

July 4, 1913. Just two months ago.

Grace had been so happy, full of hope for the first time since she’d buried Rose nine months earlier. Daisy would be baptized that morning. Since baptism could only be performed after a profession of faith, the elders saw fit to limit the practice to those nine years and older. With the girls only eleven months apart, they probably would have accepted Violet’s profession of faith as well, but Grace thought it best for each girl to have her own special day.

Grace had even put on the new straw bonnet that her sister Hattie had ordered from Montgomery Ward’s summer catalog. She’d never worn so fancy a thing before. A band of moss-green silk circled the bell-shaped crown. A single quill shot out from three crimped rosettes, nestled in the seam of the brim. Topped with such beauty, Grace dared to walk a little taller that morning, not in a prideful way, not that she could see, just a little taller.

But Myrtle Evans had to have her say even before the service started. “A bit fussy for the Lord’s house. Some might even say improper.”

“Jesus must have liked fine things,” Grace replied with a smile. “The Bible tells us they cast lots for His garments.”

After church, Grace stomped through her kitchen, yanking flour off the shelf, slamming lard onto the table. Although Myrtle’s remark had irritated her, the fact that she took satisfaction in her own response bothered her even more. “Lord, I know full well that pride goeth before a fall,” Grace said aloud, working the lard into the flour with a sprinkle of cold water. “I’m heartily sorry for my sinful ways. Amen.”

She’d decided to make a huckleberry pie for Daisy. Why not indulge her? After all, it was her baptism day, and later they’d be going to the Providence Christian Church’s annual picnic, one of the rare days the mines shut down in Scranton.

She looked up to see Daisy stroll into the kitchen. She twirled once, the air opening the pleats on her store-bought dress, a one-time indulgence.

“When did you become old enough to be taken into the church?” Grace’s eyes locked on her daughter. “So grown up. My pet. Be marrying you off before we know.” She pushed a colander of huckleberries in Daisy’s direction.

“Never,” Daisy laughed. “Though I expect I’ll be promoted to the Junior Choir, seeing I’m a member now.” She picked through the berries, tossing the green and the spoiled into a bowl.

“More than likely.” Grace dropped the ball of dough into the bowl to rest and turned to adjust the damper on the stove.

Daisy began singing. “I come to the garden alone . . .”

“My favorite,” Grace said. “Get Violet to play the piano. I love to hear both my girls.”

Daisy stood up, took two steps toward the parlor, and called, “Vi-o-let!”

“If I’d wanted someone to stand in my kitchen and yell, I’d have done so myself.”

Daisy moved into the parlor and turned down the hall of their one-story house toward the bedrooms, Grace and Owen’s on the left, the girls’ on the right.

Grace picked up an empty milk bottle and began to roll out the crust. Two things she knew how to handle, piecrust and babies. And babies. She shook off the thought before it had a chance to take hold. “Lord, I’m grateful for the ones you let me keep. Amen.”

Two pairs of feet marched back into the kitchen, but Daisy pushed through the doorway first. “Tell Violet to listen to me.”

“I’ll do no such thing.” Grace stirred the berries into a bath of butter and cinnamon sugar and poured the mixture into the pie shell.

“Daisy is telling me what to do again.” Uneven bangs framed Violet’s angry brown eyes, the cropped hair a reminder of a lice incident earlier in the summer.

“I’ll not have bickering today of all days.” Grace bore three finger holes in the middle of a second crust, lifted it on top of the pie, and pinched the two shells shut with thumbs and forefingers. “And you,” Grace nodded toward Daisy as her elbow landed in her sister’s side. “What kind of example are you setting?”

Daisy dropped her arm and stared at the floor. Grace lifted the pie and stepped toward the oven. She looked back briefly to see if the girls were behaving and caught sight of Violet shoving her hip into her sister’s side. Daisy teetered, and for a split-second, Grace thought Daisy might grab hold of the table and save herself. They both locked eyes as Daisy missed her chance, knocking into Grace and tumbling to the floor with her mother and the pie.

“Owen!” Grace yelled loud enough to be heard out on their front porch, and the front porches of the neighbors on both sides. “Take hold of your girls before I get my hands on them.”

* * *

Grace lined the ffagod on a plate wondering how she could have been so angry over a pie. If only I’d been more patient that day. If only I hadn’t taken Myrtle’s comments to heart. If only I’d worn my cloth hat to church. Sobbing, she wiped her hands on her apron and went back to her bedroom.

* * *

After fishing all afternoon with Stanley, Violet arrived home late to find uncooked ffagod on the table and her mother in bed. She wanted to feel relieved about the lies she wouldn’t have to tell, the day she wouldn’t have to explain, but fear kept tugging on her sleeve. She wondered about her father and the late hour, then set her attention to finishing supper.